Through a life of sports, politics, and public service, jewelry-making has remained his first love.

Ben Nighthorse Campbell never wanted to be in politics; his first love was jewelry. Campbell was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1986 and then served as a senator for Colorado from 1993 to 2005. A Northern Cheyenne member, he put in time on the National Parks Subcommittee and fought hard for pro-Indian legislation.

But most days in session, Campbell carried around an unfinished ring or bracelet in his pocket, itching to get home and complete it or start a new piece.

“I had always been a reluctant candidate. I really just wanted to make my jewelry, but I was talked into running for Congress,” says Campbell, 83, by phone from his home in Colorado. “I commuted to Washington every week, and I had a little shop set up in both places.”

Campbell started learning how to make jewelry at age 12 from his father, Albert Campbell, a Northern Cheyenne descendant who’d learned the craft from Navajo friends before World War II. In those days, the process involved melting down coins, which were then poured into a mold. The labor-intensive work included long hours of kneeling, softening the metal, and pounding out designs.

Campbell developed both strength and a passion for the craft while working long hours alongside his father. They would trade their finished pieces for necessities such as food.

“In those days, it wasn’t like now,” Campbell says. “Everyone was poor including us, so we didn’t sell anything for money. It was a lot of work.”

Campbell didn’t realize he was creating art people would spend money on until he was living in Sacramento, California, in the mid-1960s. He moved there after serving in the Korean War and traveling as a professional athlete. He’d competed worldwide in the sport of judo, even joining the first American team at the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo. There, he tore his ACL, ending his athletic career.

So he retired to California and became active in Native American affairs, working at a halfway house and counseling inmates at Folsom State Prison and occasionally San Quentin. One day on his way home, he wandered into an American Indian arts and crafts store. Hanging on the wall was a piece of jewelry he recognized from his childhood.

“I asked the woman who owned the store — her name was Peggy Puffer — where she got that piece, and she said she bought it a long time ago, didn’t know where it was from,” Campbell says. “I told her, ‘I know where it’s from, I made it as a boy.’ ”

She asked him to make something new for her. He unpacked the tools he’d inherited from his father and brought her a bracelet the next day. She offered him $500. From there, with the help of Puffer, Campbell began entering juried art shows and competitions.

One of his first competitive pieces, a small buffalo sculpture, took first prize among 1,200 entries at the California State Fair. His rings took first prize at the Gallup Intertribal Indian Ceremonial and then were well received at the prestigious Santa Fe Indian Market, among other places.

Campbell always kept another job in addition to his burgeoning jewelry practice. He was a teacher in California, a deputy sheriff, and he and his wife, Linda, raised horses. In 1978, they left California for the mountains of Colorado, just southeast of Durango.

It was a couple of years after the move that Campbell first became involved in politics. Two terms in the Colorado State Legislature paved the way for his elections to the U.S. House and Senate.

One creative hiccup regarding his public service: While working in Congress, senators and representatives aren’t allowed to earn outside income, so Campbell couldn’t enter competitive shows. But he never gave up the craft of making jewelry.

Much of his life’s work has been dedicated to the art of Indian jewelry and the preservation of the greater culture. While in office, he worked to pass the Indian Arts and Crafts Act in 1990, which created a standard of truth in advertising for shops purporting to sell products in the style of a certain tribe.

“You can’t claim a piece of jewelry is Navajo if it’s not,” Campbell says. “Navajo-style is fine, but it’s important it’s not misrepresented by the person selling it.”

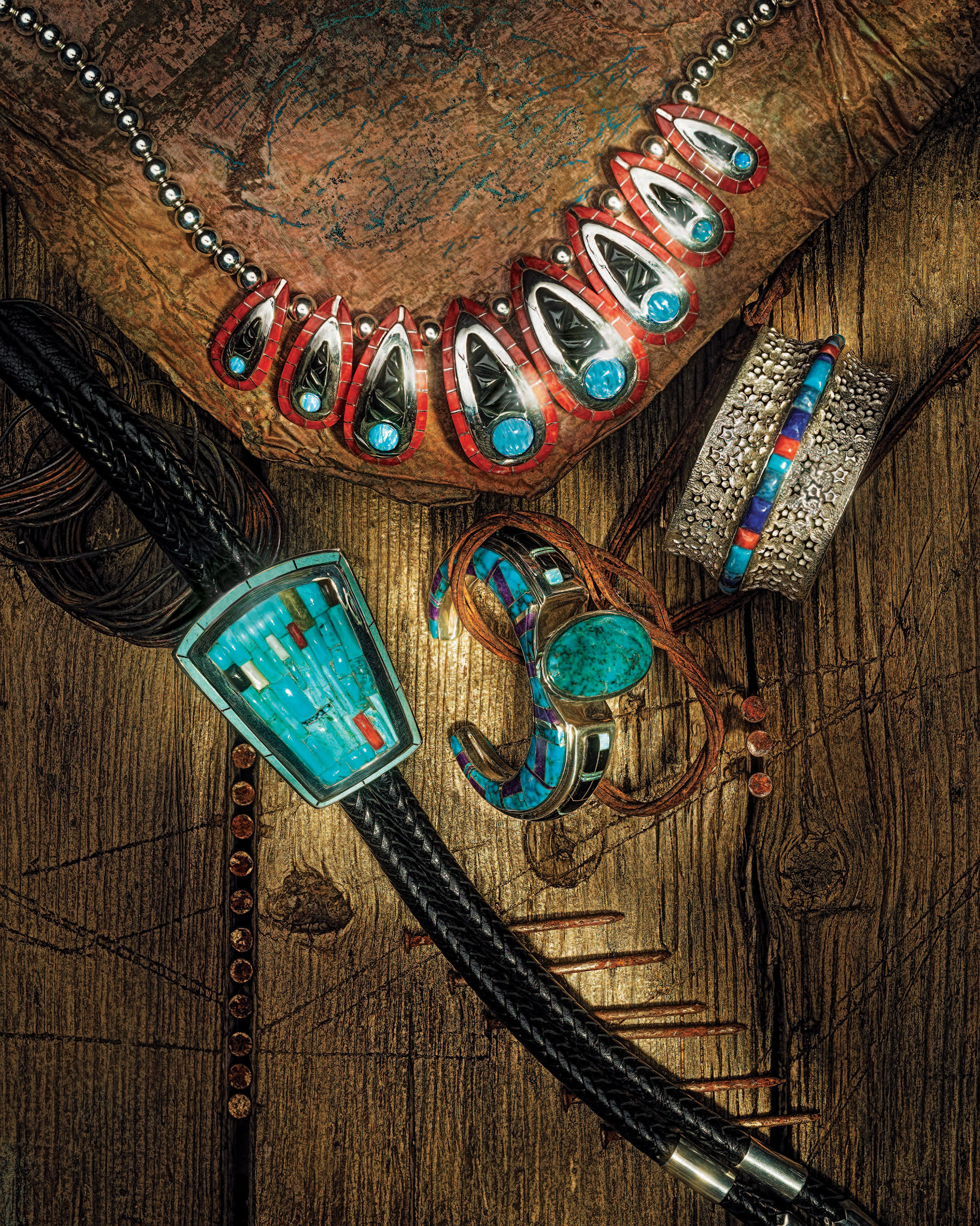

At the end of his second term in the Senate, Campbell decided not to run for re-election. Instead, he returned home to his family, his horses and his jewelry. These days, Campbell wakes up early, hits the gym, and spends hours in the shop working on his signature style — something he describes as “Southwest contemporary.”

His work is sold at the Durango and Santa Fe locations of Sorrel Sky Gallery, owned by his daughter. Notables such as Robert Redford and President Bill Clinton own pieces by Campbell. For a period of time, Colorado gifted a piece of his jewelry to anyone who worked on a film in the state.

Campbell says he’s not done making jewelry anytime soon. “I think the older an artist gets, the better they become,” he says. “I’ve got so much to do with my life.”

Find out more about Ben Nighthorse Campbell’s life and see more of his work online.