The author had a special connection to Sun Valley, where he hunted, fished, found his “Family,” and was laid to rest.

People here think he was talking about himself, too, that day. Ernest Hemingway stood in the middle of the Ketchum Cemetery, 40 years old and at the height of his career as a writer, reciting a eulogy he’d penned for a man he’d known only a few weeks. Gene Van Guilder was a publicist for the Sun Valley Resort, just outside the tiny city of Ketchum, and part of the team that had brought the famous writer to the hills of Idaho. His widow had asked Hemingway to write something about her husband after he died in a hunting accident. What Hemingway wrote seems much more poetic than the sparse style he’s known for. He talked about Van Guilder’s skills as a communicator, his generosity, his lust for life, and his love of nature.

“He loved the warm sun of summer and the high mountain meadows, the trails through the timber and the sudden clear blue of the lakes,” Hemingway wrote. “He loved the hills in the winter when the snow comes. Best of all he loved the fall ... the fall with the tawny and grey, the leaves yellow on the cottonwoods, leaves floating on the trout streams and above the hills the high blue windless skies. He loved to shoot, he loved to ride and he loved to fish. Now those are all finished. But the hills remain.”

This was 1939, during Hemingway’s first trip to Idaho. He was already a celebrity by then, and his second marriage, to Pauline Pfeiffer, was falling apart. The Sun Valley Lodge was new at the time, and in an effort to drum up publicity, executives invited a number of Hollywood stars. Gary Cooper, Clark Gable, and Lucille Ball were all regulars. Hemingway drove up from Wyoming in early autumn with Martha Gellhorn, the war correspondent who would become his third wife. They stayed for free in Suite 206 at the resort, a place he would later dub the “Glamour House.”

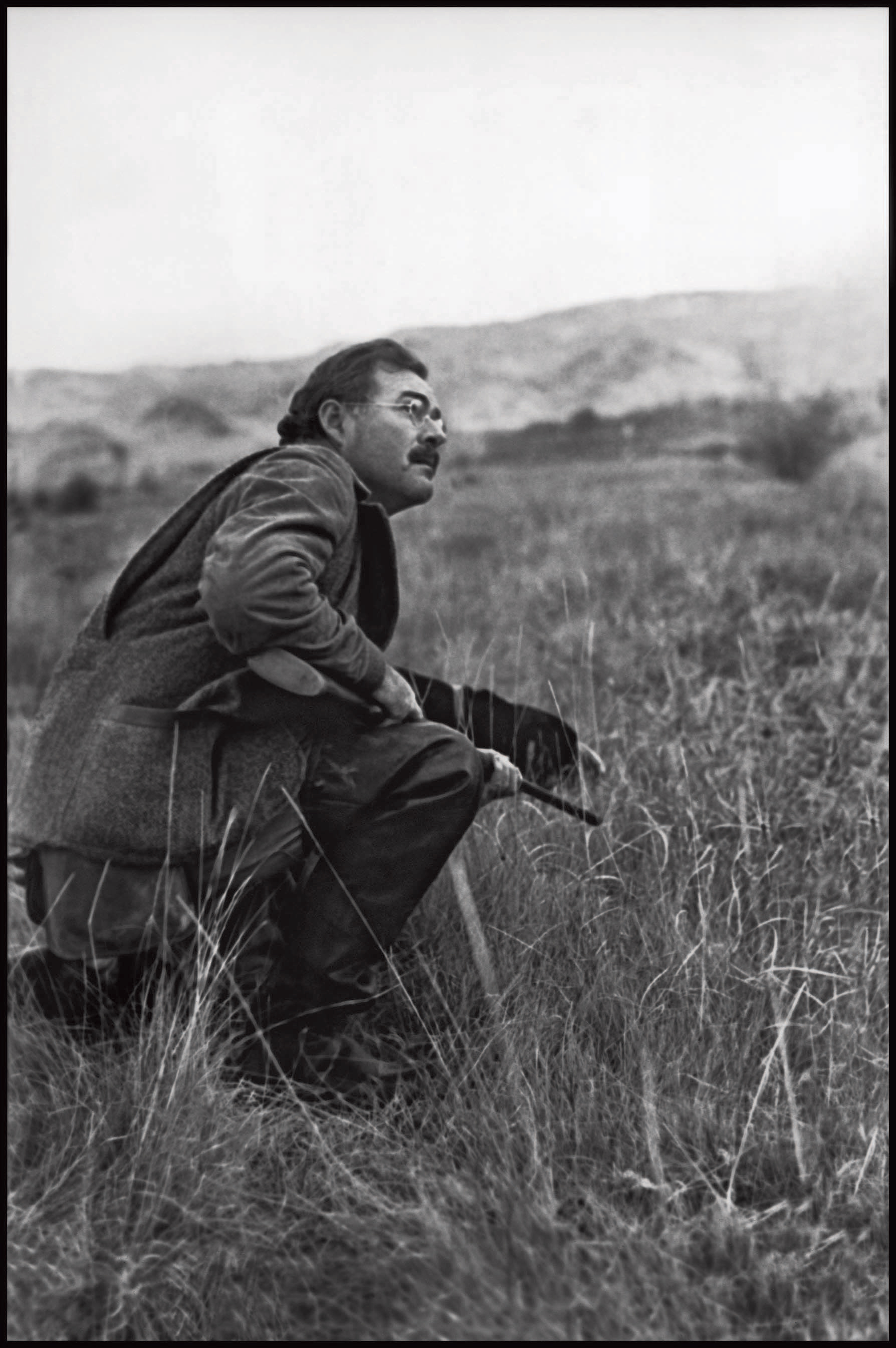

Hemingway was mustachioed, with dark hair slicked back and a broad chest. He was at work on For Whom the Bell Tolls, his epic about the Spanish Civil War, and the hills here reminded him of the countryside in Spain. He’d wake early and work on the book, eat marinated herring and drink beer for breakfast, and then spend the afternoons shooting. He didn’t like the other guests as much as he liked the locals — the skilled outdoorsmen and guides. He befriended the lodge photographer, Lloyd Arnold, and his wife, Tillie. The resort’s chief guide, Taylor Williams, became Hemingway’s regular hunting partner.

When the season was over, Hemingway went home to Cuba, but he had a special connection to Idaho. He traveled to and wrote about places all over the world, sending young dreamers to the woods of Michigan and the beaches of Key West, to the cafes in Paris and bullfights in Pamplona, Spain. He worked on several stories and books here, but, aside from that eulogy and a single 1951 hunting article for True: The Man’s Magazine, he never wrote about Sun Valley, a place he’d return to many times throughout his life.

Hemingway was easily America’s most celebrated — and criticized — writer, a character who transcended literature to epitomize all that was good and bad about 20th-century masculinity. But here, he was just Papa. So much of his life was filled with violence and war. Here, it was quiet. This was his escape, his respite. And this was where, in a house along the Big Wood River, he put a shotgun to his own head and left this world.

Like a lot of writers have, I’ve come to Sun Valley to pay homage to the literary lion, the man whose name still conjures notions of adventure. Like a lot of writers — especially men — I grew up mimicking him, thinking of him as a hero: not just the short sentences, but also the drinking, the fighting, the wanderlust. And like a lot of writers, I long ago dismissed most of that as silly machismo. But his effect on our culture, both the way we tell stories and the way we think of masculinity, is indisputable.

You can’t pass through Sun Valley without noticing the same incredible landscapes that struck Hemingway on that first visit. The bright reds and yellows of the leaves, the tall spruce pines, the way the clouds seem etched so gently in the soft blue sky, the glistening streams cutting through the golden fields, and the mountains and hills that seem to cradle the area, protecting everything here from whatever might be on the other side.

I stand outside the balcony of Suite 206 at the lodge, imagining Hemingway there typing every morning. I go by the Trail Creek Cabin, and to Christiania, which is now owned by former alpine ski coach Michel Rudigoz, and sit at the table in the corner. I have drinks at the Casino, where the short archway by the door seems like a portal to another era. Through the Sun Valley tourism bureau, I meet Wendy Jaquet, the former state representative from Ketchum, who knows every person she sees — and everything about Hemingway’s time here. She also gives guided tours.

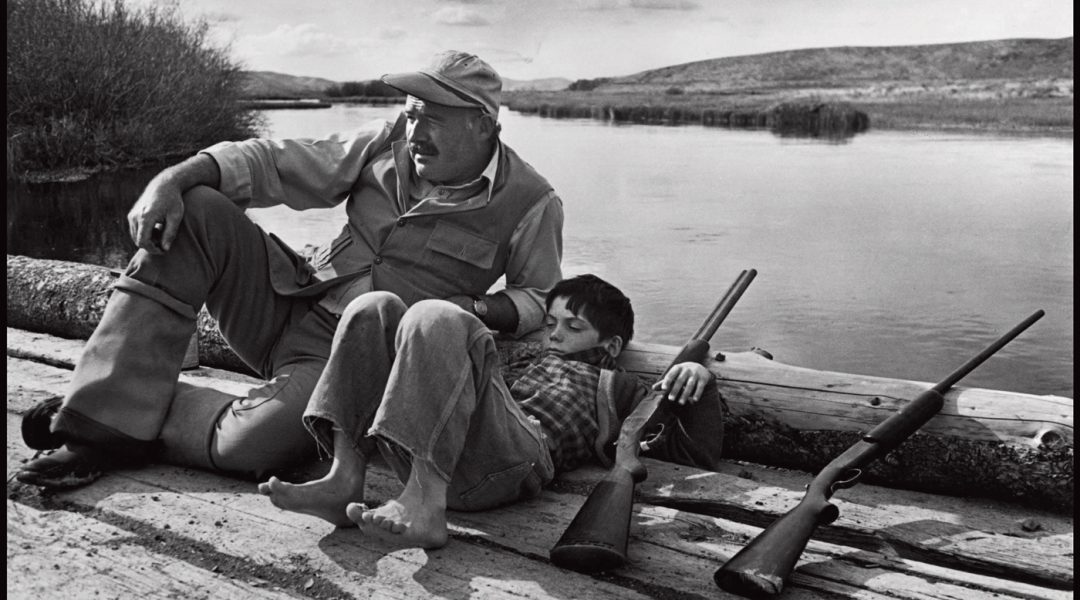

Hemingway came back to Ketchum in the fall of 1940 with Martha and his three sons. He finished his book that year, sending the final pages from Sun Valley. He went back the year after that, too, after he sold the movie rights to For Whom the Bell Tolls for $150,000, a record at the time. He spent his days in the fields with his Idaho friends. Women and children were invited, too, and if someone didn’t have their own gun or reel, Hemingway would buy a new one, custom-made. He relished the opportunity to teach someone how to shoot or cast a line. They hunted everything from ducks, doves, and magpies to pronghorn and elk. Associates from those days later described a man with immense respect for these animals — and an obsession with killing them.

On days when they didn’t kill their own dinner, the group dined at the Trail Creek Cabin or the Ram Bar or the Duchin Lounge. They’d drink at the Alpine (now Whiskey Jacques) or the Casino bar. Hemingway had his own table at Christiania, in the middle of town — locals still debate which corner it was in. The author, whose life had been filled with violence and contentious relationships, began referring to the Sun Valley cohorts he saw every fall as “The Family.”

From December 1942 to December 1945, during the height of World War II and a few months afterward, the Sun Valley Resort was closed and used as a Naval retreat, reopening on December 21, 1946. Hemingway came back after the war with a new wife, Mary, and continued where he left off with his friends. He returned to Idaho every fall for the next few years, but in January of 1948, he and Mary left for Cuba and didn’t come back for a decade.

The Hemingway who returned in 1958 was different. He still went hunting and fishing with the Arnolds and his other friends, and he worked on The Garden of Eden and A Moveable Feast (both published posthumously). But he was nearly 20 years older than when he first visited Idaho, and his physical and mental health were slipping. In 1959, amid the political instability in Cuba, he moved his massive collection of documents to Idaho where he hoped the dry air would help preserve them. He and Mary bought a furnished two-story house with reinforced concrete walls and 14 acres looking out over the Sawtooth Mountains.

He’d won both the Pulitzer and the Nobel Prize by then. He’d also survived two devastating plane crashes in Africa, a lifetime of war-related injuries, several shark-hunting accidents, multiple car and motorcycle crashes, and at least a dozen concussions. Friends reported seeing him timid and confused, with none of the striking charisma they’d come to know. In an effort to treat his depression, Mary had him committed to the Mayo Clinic in November 1960, where he was given electroshock therapy. Hemingway was sent back to the clinic for more of the same in the following spring. On July 2, 1961, he woke up early, loaded two shells into his favorite shotgun, went to the foyer at the bottom of the front stairs, and killed himself. Though she’d tell the truth in interviews years later, Mary told reporters at the time that he’d been cleaning his weapon when it went off.

The Sun Valley Museum of History has an entire wing dedicated to Hemingway. There’s a typewriter and case — replete with stickers from Spain and Cuba — that he left with Lloyd and Tillie Arnold. There’s the doctor’s kit that belonged to Dr. George Saviers, the man who treated the writer at the end of his life. There are photos of Hemingway hunting with Gene Van Guilder and Taylor Williams, fishing with Gary Cooper, picnicking out in the fields with eight or nine people.

At the museum, I meet Taylor Paslay, the museum’s operations director. Paslay, who has both handyman skills and an English literature degree, lived in the converted basement of the house where Hemingway killed himself. Paslay worked for The Nature Conservancy, which owns the home. He shares stories about the bidet there, and the years he spent fixing the walls and reading the documents. “I actually lived there for longer than he did,” he quips.

Next the tour guide Jaquet takes me by a barn full of old ore wagons that the town brings out for parades and celebrations. She explains the mining history, and how William Averell Harriman, chairman of the Union Pacific Railroad in the early 20th century, had the idea of a remote resort town that only his railroad could get to. She also takes me by the adorable craft shops and stores and restaurants in town. Before she leaves, she invites me to the The Community Library, where an expert is giving a talk about how Basque immigrants first moved sheep through the local mountains.

That evening I go to the Ketchum Cemetery. There in the back, bracketed by tall spruces, is a slab of stone marked ERNEST MILLER HEMINGWAY July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961. On the granite are hundreds of pennies — previous tributes — along with an empty bottle of absinthe, a nearly empty bottle of scotch, a tiny bottle of rum, and a few pens.

Next to Hemingway’s grave is Mary’s, and there are a few pennies on hers, too. A few feet away are the graves of Hemingway’s son Jack and a few of his grandchildren. And a couple feet in the other direction are the graves of the Arnolds and Taylor Williams and the marker for Gene Van Guilder. Here, he’s surrounded by The Family.

A few miles away, in a small alcove on a bent stream, is the Hemingway monument. It’s a bronze bust, facing the mountain and surrounded by the golden leaves. Friends and family put it up five years after Hemingway’s death, a modest way for a town to honor a man who could escape here. Inscribed beneath the bust are words he wrote on that first trip to Sun Valley:

“Best of all he loved the fall

The leaves yellow on the cottonwoods

Leaves floating on the trout streams

And above the hills the high blue windless skies

... Now he will be a part of them forever”

From the July 2016 issue.