The Navajo artist's love of animals inspires her colorful creations.

Melanie Yazzie has just come inside from walking her dog, a bearded collie named Gus Gus (after the fat mouse in Cinderella), at the home she shares with her husband, Clark Barker, an abstract painter, in the suburbs of Boulder, Colorado. It’s not far from the University of Colorado, where she’s a professor of printmaking, but that’s not why they’re living there. “It was for the dog!” says Yazzie, who grew up on the Navajo Nation in Ganado, Arizona, where all of the animals roamed free, just as they do in her paintings, prints, and sculptures.

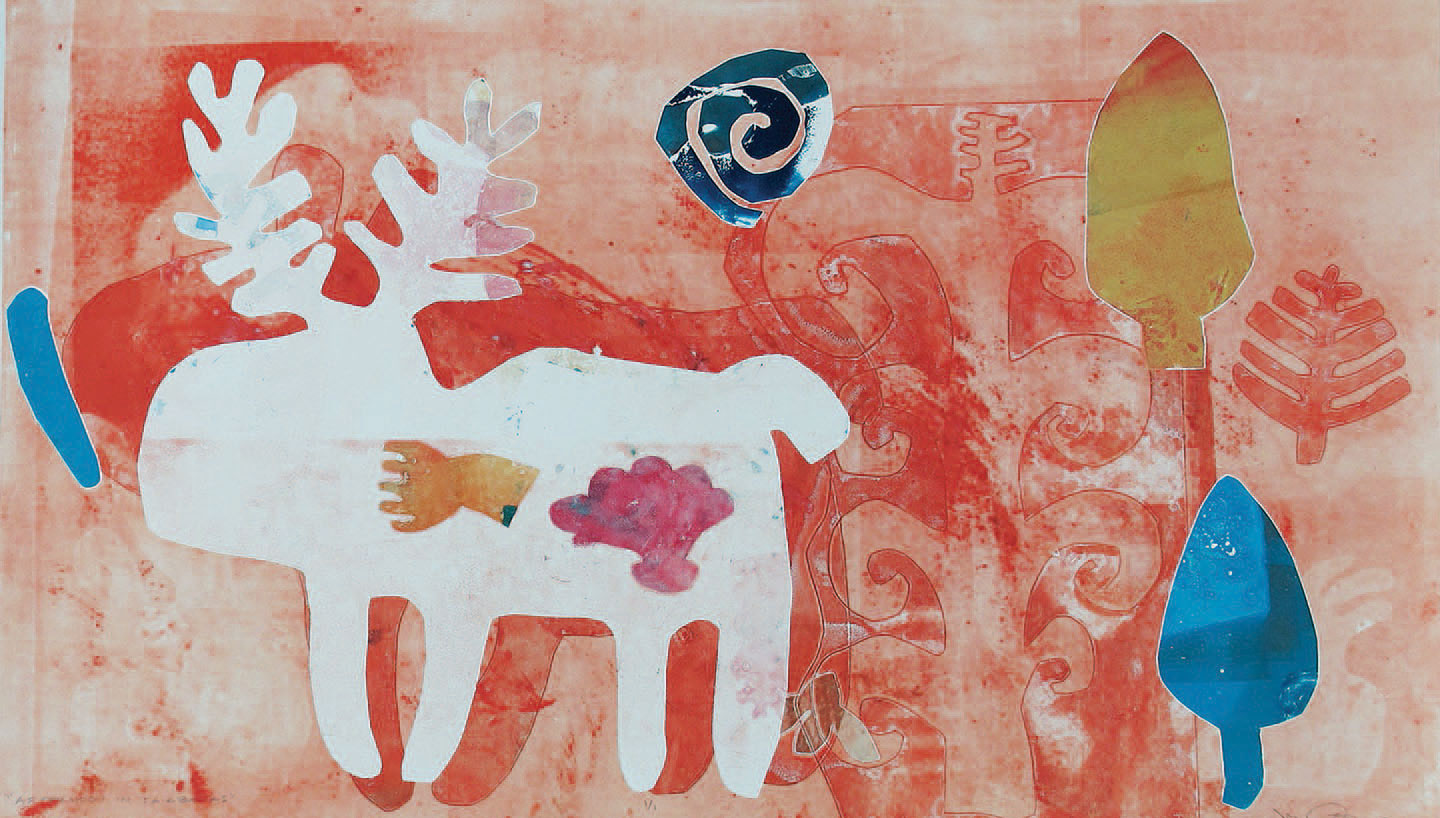

Whether it’s an image of an orange dog with puffy blue rain clouds scattered all around or a pink polka-dotted critter that might be a dog, a cat, or a little of both, Yazzie’s animals bring her artwork to life in all their whimsical glory. “It’s not unusual for my animals to be wearing cowboy boots or riding in their own car,” she says.

With her brand of joyful imagination, Yazzie could win a Caldecott Medal if she ever decided to illustrate a children’s book. But this is actually deceptively grownup stuff: Yazzie has had more than 100 group and solo exhibitions around the world, and her work is held in prestigious museums, from the National Museum of the American Indian and the Denver Art Museum to the Kennedy Museum of Art and the Rhode Island School of Design Museum.

A Navajo of the Salt Water and Bitter Water clans, Yazzie purposely blurs the lines between fact and fiction in pieces inspired by the animals she knew on the reservation. “When you live in a small area where all of the cats and dogs are inbred, there’s some wackiness that goes on and sometimes they look kind of strange,” she says. “The relationships between the animals were different. The dogs and the sheep, they were friends, and they would take care of each other. My grandfather’s dog, Beebee, would jump on the back of the horse and ride.”

These playful, lyrical images — dogs on horses, animals as pals, along with imagery that appears in her dreams — are recurring motifs. They appear in bronze sculptures, multilayered monotypes, and paper paintings created with colorful paper pulp applied via squeeze bottles.

“My grandma would see Navajo designs [based on images of sand painting Yeis, Navajo gods that keep the world in balance] on curtains or on placemats in restaurants and she said those images were important — they shouldn’t be used that way. The way I draw and make my work comes from trying to respect that. That’s why I tried to come up with my own symbols to tell my stories.”

Storytelling, Yazzie says, is her art’s chief aim. It’s rooted in her Navajo heritage. “The artworks stem from the thought and belief that what we create must have beauty and harmony from within ourselves, from above, below, in front, behind, and from our core,” Yazzie explains in a recent artist statement. “We are taught to seek out beauty and create it with our thoughts and prayers. I feel that when I am making my art — be it a print, a painting, or a sculpture — I begin by centering myself and thinking it all out in a ‘good way,’ which is how I was taught from an early age.”

It wasn’t always so. After graduate school, Yazzie’s paintings were downright heavy. But she found that focusing on the reality of her tribe was so depressing that people tuned out when she spoke to them about it. Then her health began to suffer. So Yazzie began creating art that was happier. “The work changed to creating a beautiful place and a calm place,” she says, “and I started educating a lot of different people.”

Today when she speaks to groups about how living on the reservation influenced her as an artist, it’s a short segue to a discussion about the current state of affairs on some reservations, including her own, where many live in poverty with no running water or electricity. “I’ve educated more people about what it means to be a Native American with this whimsical work,” she says. “I know these paintings empower people.”

Melanie Yazzie is represented by Glenn Green Galleries in Scottsdale, Arizona, and Tesuque, New Mexico.

From the May/June 2016 issue.