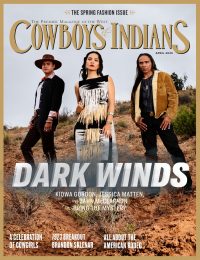

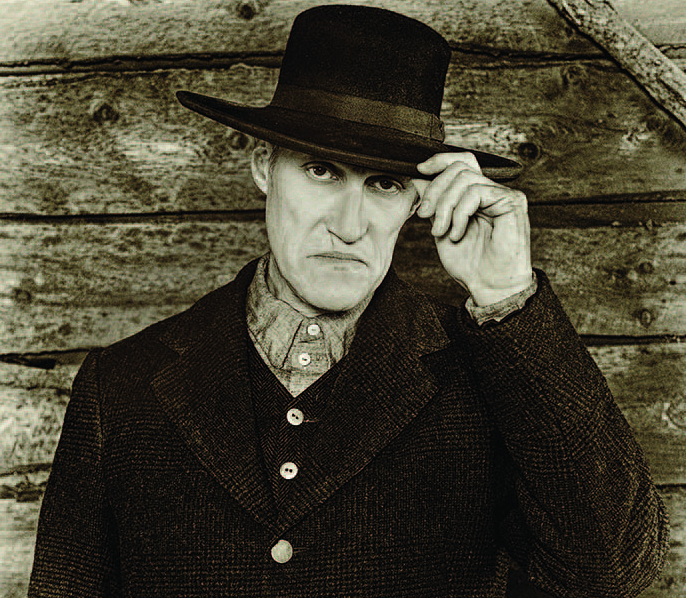

The post-Civil War drama “Hell on Wheels” begins its final run in June. Star Anson Mount reminisces about his five years on the Transcontinental Railroad and what he’ll miss most after wrapping the story of the reuniting of the nation.

Even though Anson Mount was fully aware that the end was near, he was stunned when it finally arrived. And he wasn’t the only one.

“It was the weirdest thing,” he says, recalling the final day of shooting for Hell on Wheels, the gritty AMC western drama that returns for its climactic final seven-episode run in June. “And I think it was the last thing any of us expected when we were on the last setup.”

Mount and his fellow players were shooting the last scene for the series finale, and they expected to spend an inordinate amount of time on take after take until every detail was spot-on perfect. “But after we did just one take, David Von Ancken — who was the director of the final episode and, fittingly enough, was the director of the pilot — walked out from behind the camera and just said, ‘That’s it. We don’t need another take.’

“And, like I say, it was weird. Nobody knew what to do. It was like just this pall went over the whole set. And then, slowly, people started shaking hands and, before you knew it, we were out on the front lawn of this house that we rented, and we were popping Champagne.”

And so the five-year journey of Hell on Wheels drew to an unexpectedly — but, perhaps, appropriately — sedate conclusion.

When the series premiered on November 6, 2011, it began as a classic post-Civil War tale of retribution and revenge, introducing Cullen Bohannon, the Confederate Army veteran played by Mount, as a man implacably obsessed with finding, and killing, the Union soldiers responsible for the wartime deaths of his wife and son. (In the very first scene of the debut episode, Cullen dispatched one of the perpetrators — blam! — in a church confessional.) His relentless pursuit took him westward, where he signed on as a foreman for the Union Pacific Railroad in the hope of tracking down another culprit. The show’s title, it should be noted, doesn’t refer to Cullen himself, but instead describes the itinerant “town” of gambling houses, dance halls, saloons, and brothels that trailed construction gangs building the Transcontinental Railroad through the American wilderness. Nonetheless, Cullen certainly appeared hellbent on meting out rough justice, even as he proved himself exceptionally well-suited to the job of walking boss.

Right from the start, Mount — along with series creators Joe and Tony Gayton — saw Hell on Wheels as something more substantial than a period drama about the slaying of villains and the laying of track. As he told C&I back in 2011: “If we do our job right, this show isn’t just about revenge. Or even just about the building of the railroad. It’s really about the building of a nation.” More specifically: Hell on Wheels has always been about the reuniting of a nation torn asunder by war, and the healing of the men and women who were wounded, literally or figuratively, by the bloody conflict.

Over five seasons — six, really, if you count the divided-in-half fifth season as two separate cycles — faithful viewers have seen Cullen gradually, and often reluctantly, evolve from a loner intent on avenging his murdered wife and son to a member of a makeshift community who’s given a shot at redemption with another spouse and offspring. Along the way, he has run the gamut from outlaw to lawman, coldblooded killer to evenhanded leader. He has crossed paths with such historical figures as Gen. Ulysses S. Grant (with whom he forged a mutually respectful friendship) and Brigham Young (with whom he didn’t), developed a complex and ultimately tragic bond with former slave Elam Ferguson (memorably portrayed by rapper-actor Common), and sustained an on-again, off-again, almost familial relationship with Thomas C. Durant (Colm Meaney), a real-life railroad tycoon whose murderous tendencies seemed to increase even as Cullen started to curb his own violent impulses.

(Throughout the run of Hell on Wheels, Mount says, “We just kept going back to this idea of this contentious father-son relationship” between Cullen and Durant. “So the prodigal son theme was returned to several times. And I think that people are going to be very, very pleased with how the Cullen-Durant relationship gets resolved in the end. I think it’s one of the best parts of the end of the series. I really do.”)

And then there’s Thor Gundersen — better known as The Swede, even though he’s Norwegian, and brilliantly played by Christopher Heyerdahl — a cunning and cadaverous sociopath who was introduced in the show’s second episode as an unforgiving enforcer bent on executing Cullen and has made a major nuisance of himself ever since. Much like Cullen, The Swede has repeatedly reinvented himself, sporadically leaving dead bodies in his wake as he transitioned from railroad factotum to Native American rabble-rouser to faux Mormon bishop. The only constant has been his perverse fixation on Cullen — with whom he sees himself as inextricably connected — and his determination to make Cullen’s life a living hell. Indeed, at the cliffhanger conclusion of last summer’s final episode, The Swede was dead-set on killing Naomi (MacKenzie Porter), Cullen’s estranged Mormon wife.

“I’ve always felt Cullen and The Swede had a very difficult relationship,” Heyerdahl says, chuckling at his own understatement. “If you just let them go at it with each other, only one would survive. Because otherwise, they would just go at each other until the end of time.” Even so, “There is a love there,” Heyerdahl insists. “I can only speak, of course, from my side, but I always felt that The Swede loves Bohannon. He loves him in a way because he gives him a reason for being. He is the reason he fights for his idea of justice. He is the epitome of how the Old Testament is so unforgiving in its handling of justice. Justice is very clear in that Scripture, and I think that that’s something he holds onto as a way of surviving.

“The interesting thing is that he is also prepared to modify his perspective on the world. He’ll say, ‘Oh, I admit I’ve made a terrible mistake. It turns out that you’re not lucky. I’m lucky.’ Or, ‘I’m not the devil. I’m God.’ Or, ‘It turns out, you’re not Satan. I’m Satan.’ Or vice-versa. He is constantly trying to find his place in the world. And Bohannon seems to be his divining rod for what his place in this world is.”

In a not dissimilar fashion, Heyerdahl has looked to Mount as a lodestar during the long, strange trip of Hell on Wheels. “Watching Anson take that character and make Bohannon his own is a great gift. To be able to see him go from what Bohannon was, or how he knew Bohannon from Season 1, to where he ends up at the end of [the series] is remarkable. He brought such life and such depth to the role. And he’s a wonderful leader. He led us all on one hell of a journey.”

Mount is quick to return the compliment, praising Heyerdahl for having “an incredible combination of being unbelievably focused — and it appears in his work — and yet also being a very approachable, fun goofball at the same time. I’ve definitely — definitely — learned the importance of keeping things light, particularly on the set during the heavy drama, from Chris.”

As for the ongoing animosity between their two characters, Mount agrees that “The Swede believes that Cullen is the devil, or at least his devil. ... He believes it’s his duty to reveal to Cullen his true nature — Cullen’s true nature. And it’s true that in many ways, they’ve both driven each other to be better at what they do because of the other. The Swede points out an enormous amount of similarities between the two of them. I really can’t say much about it, but by the end of the season, you’ll see that things [have been] drawing toward that.”

So how does this conflict finally resolve? Does The Swede finally get force-fed his just desserts? Does Cullen live happily ever after? Mount and Heyerdahl know, as does executive producer and showrunner John Wirth. But all three of them are keeping their cards close to their vests.

“Well, the show ends with the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad,” Heyerdahl says with a reasonably straight face. “So let me just say that there’s a golden spike involved.”

“Let me put it this way — The Swede’s story gets resolved,” Wirth adds. He is a tad more forthcoming about Cullen’s fate, noting that, all along, “I think he wasn’t reconstructing himself into the man that he was before the war started and this whole journey of Hell on Wheels started for him. I believe he was constructing himself into the man he would have wanted to be, knowing what he learned through his journey ... and applying it to who he was before he got gobbled up by the Civil War.

“I think he’s a far different man by the end of the series than he would have been had the war never happened and he stayed in the South and continued to be a husband and father and plantation owner.”

Just how difficult was it to reach the end of the line for Hell on Wheels? “It’s definitely bittersweet,” Wirth says. “Driving the golden spike represented the end of this grand enterprise, which was to build the First Transcontinental Railroad. It was also the beginning of industrialized America and a new way of doing business. It revolutionized travel. It was the beginning of many things. But when it was completed, people went on to the other things.

“There are a number of different ways to experience the end of something, and I was very interested in exploring that during this final season. Because not only was it happening on the show for the characters who populated the show, but it was happening to all of us. We were all experiencing the very same thing.”

Hell on Wheels wasn’t Anson Mount’s first rodeo — his résumé also includes roles in the TV series Conviction, Third Watch, and Line of Fire, and an acclaimed performance in the 2009 indie film Cook County — and he’s already pursuing other acting challenges on stage as well as in television and movies. But giving up Cullen Bohannon hasn’t been easy.

“I’ve never played a role that was this size, or became this size,” Mount says. “I really grew to love the process. I grew to love long-form drama and just getting to know the character to the point where I can show up at 5:30 in the morning, dog-tired, just slip on the boots — and I’m there, you know. That I enjoyed a lot, and I think that made me a better actor.

“What am I going to miss the most about the show? Being underneath those skies on the back of a horse. I finally understand why all those guys in the ’50s and ’60s did back-to-back westerns — because they got to be outside. And I dread ... well, I’m really hoping not to go into a show that’s shot completely in a studio.”

Mount admits that when compared with some of the show’s most demanding and emotionally draining episodes — especially those involving the deaths of Elam, who never quite recovered from his close encounter with a grizzly, and minister turned avenging angel Ruth Cole (Kasha Kropinski) — “I don’t think the last episode was one of the hardest ones. I think it’s a tremendously optimistic ending.”

And there was an epiphany to boot. Mount won’t let on exactly when or where it happened, but there was a moment while the cameras were rolling, and “I was trying to figure out what the whole thing was about — and it was one of the greatest moments that I’ve been able to experience as an actor. And I do not claim credit for it. I’m firmly in the mind that we as artists — we are just the wire. We are not responsible for the electricity. And there’s a moment where I just got jolted with about 10,000 volts.

“It was all pretty much a cakewalk after that.”

Hell on Wheels returns for its final episodes June 11 on AMC.

From the May/June 2016 issue.