Before his death in 1992, Glendon Swarthout wrote The Shootist, The Homesman, and seven more award-winning stories and novels that have been turned into films. His son vividly remembers them all.

Our family always loved westerns. When I was a sprout growing up in East Lansing, Michigan, and my father, Glendon Swarthout, was earning his Ph.D. in Victorian literature and teaching honors English at Michigan State University, we had a ritual. Every week I would holster my Fanner 50 cap pistol and try to outdraw James Arness in his famous opening shootout with a bad man on TV’s Gunsmoke. My dad would distract me with jokes, usually resulting in Marshal Dillon beating me to the draw. Then we’d both settle in to watch 20 minutes of exciting life unfold in black-and-white in old Dodge City, Kansas.

My father always dreamed of being a professional writer, and he submitted short stories early in his career — and even sold a few — to magazines like Redbook, The Saturday Evening Post, and eventually Esquire and Cosmopolitan. One of them was included in a short story sampler paperback that happened to be picked up by Lost in Space writer Peter Packer in the famed Schwab’s Pharmacy in Hollywood. Packer took it to producer Harry Joe Brown, who had a two-movie-a-year deal with Columbia Pictures to make low-budget B-westerns starring his partner, actor Randolph Scott. Packer optioned Glendon’s “A Horse for Mrs. Custer” for the princely sum of $2,000 and tailored the story for an older Scott, making him a captain instead of a shavetail lieutenant and adding an officer’s sister as a love interest, actress Barbara Hale from the Perry Mason mystery series.

The movie’s title was changed to 7th Cavalry, for its plot relates what befell the remnants of Lt. Col. George A. Custer’s 7th Cavalry when it was assigned to retrieve its fallen troops at the Little Bighorn a year after the debacle. Scott plays an officer who was assigned elsewhere, and who consequently fights his guilt about missing the infamous battle while he witnesses the friction that developed among the cavalry troops who either supported or decried the fabled, fallen general. Directed by B-movie legend Joseph H. Lewis, 7th Cavalry remains one of Scott’s more interesting, historically based westerns, the only one among a number of Custer movies to examine the aftermath of his infamous “Last Stand” against the Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho.

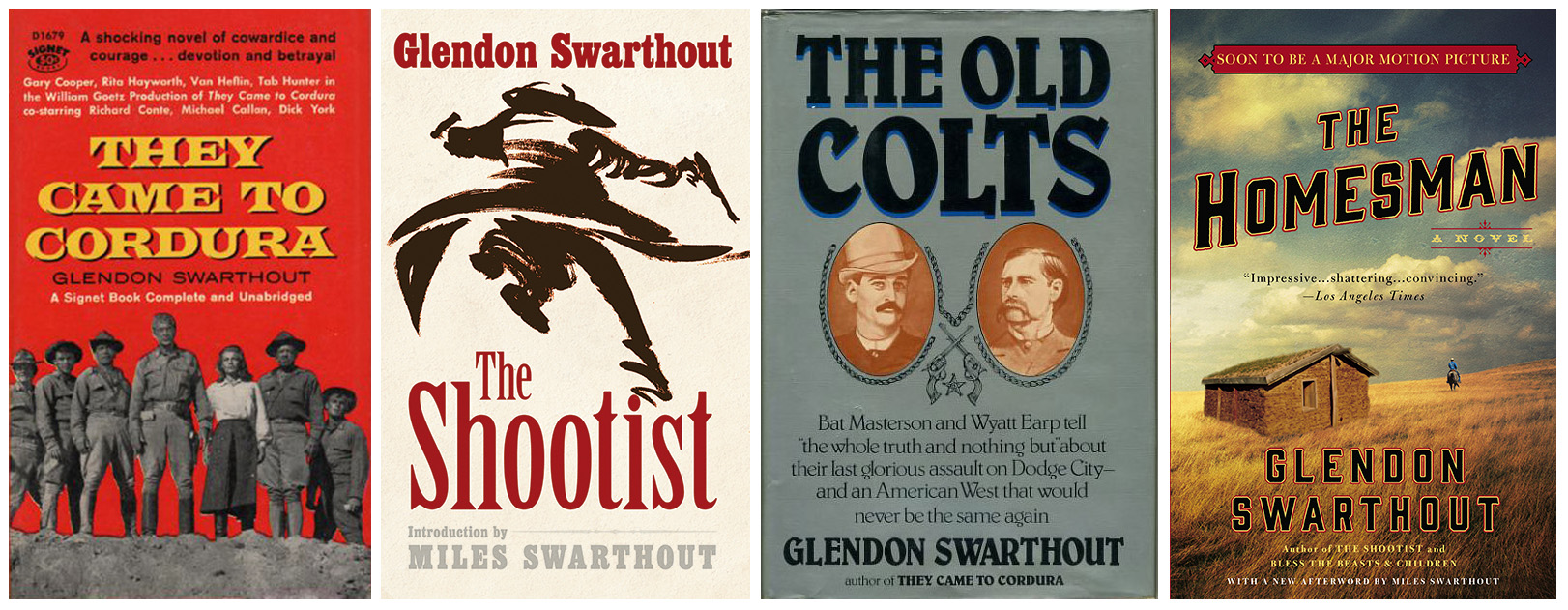

They Came to Cordura was Glendon’s breakthrough second novel in 1958. The first war novel to use Gen. John J. Pershing’s 1916 campaign as a fictional backdrop, the book told the story of Pershing’s Punitive Expedition — the U.S. Army’s first military operation to use mechanized vehicles, employing Dodge touring cars, Jeffery Quad supply trucks, and Curtiss JN-2 “Jenny” airplanes to chase Pancho Villa’s guerillas around northern Mexico for 11 frustrating months. The book received a sterling review from The New York Times Book Review, was nominated by its publisher Random House as a Pulitzer Prize fiction candidate, and quickly became a bestseller.

Columbia Pictures bought the film rights for $250,000 and hired Glendon to work on the screenplay at the studio in Los Angeles. Gary Cooper was cast as a disgraced awards officer who is ordered to escort five Congressional Medal of Honor nominees back to base at Cordura, along with a female prisoner who had given food and shelter to the Mexican enemy. The soldiers had all distinguished themselves in the last mounted cavalry attack the Army made against a foreign enemy at Ojos Azules (Blue Eyes), a large ranch owned by the prisoner, an American expatriate (played by Rita Hayworth in one of her best later roles).

The supporting actors — Van Heflin, Richard Conte, Dick York, and Tab Hunter among them — were fine in this grueling trek across desolate Mexico in 1916, but “Coop” was too old and wooden in his officer’s role, and he had evidently been diagnosed with painful cancer before filming, about which he neglected to tell the studio. They Came to Cordura was Columbia’s big-budget western ($4.5 million) for December 1959, but it wasn’t the box office hit they’d hoped for.

Glendon wrote on, a new novel coming every two years while he continued to teach college English. Where the Boys Are was a comic peek at Michigan State University kids vacationing in Fort Lauderdale, which MGM quickly turned into a high grossing, low-budget success — the granddaddy of all the spring break “beach pictures” to follow.

My parents then moved the family from Michigan snows to Scottsdale, Arizona, “where sunshine spends the winter.” Dad once again turned to his favorite genre, the American action-adventure tale — which he defined as “men with guns going somewhere to do something dangerous” — this time with a twist. The Tin Lizzie Troop is a humorous take on the same Pershing expedition he explored in They Came to Cordura from the point of view of a bunch of spoiled young lords of the Philadelphia Light Horse, who are ordered to defend the Texas border in 1916 but end up chasing Mexican banditos with a kidnapped gringa in their Ford Model Ts. Actor Paul Newman purchased the film rights in 1972, and I adapted the screenplay with my father in 1977. Locations were scouted in southern Arizona and Anthony Perkins was set to play the lead Army lieutenant before Warner Bros. Pictures suddenly pulled the financial plug on Newman’s production company in 1978.

So it too often goes in Hollywood, but Glendon had better luck when John Wayne was cast in his western masterpiece, The Shootist, which won the Spur Award from the Western Writers of America in 1975. When producers Mike Frankovich and William Self first bought the film rights, they were unable to interest any Hollywood studio in backing George C. Scott in the title role. Gen. Patton as a cowboy? No way. But The Duke had also heard about this tale of a legendary gunfighter dying of prostate cancer who rides into El Paso, Texas, in 1901 to see his trusted doctor, played by Jimmy Stewart, and lobbied hard for the part. (The location would later be changed to Carson City, Nevada, for the film.) Based on Wayne’s participation, the producers were able to raise half of the $8 million budget from Paramount Pictures for its North American distribution rights, with Italian producer Dino De Laurentiis kicking in the other $4 million for foreign theatrical rights.

A veteran supporting cast pitched in at below their normal salaries, for word had gotten around Hollywood that Wayne’s shaky health due to his earlier lung cancer surgery might well make this his last film. Lauren Bacall, Richard Boone, Ron Howard, Sheree North, and Hugh O’Brian all turned in fine performances as a prelude to Wayne’s final shootout in a fancy saloon, where he goes out with his six-shooter blazing in an attempt to rid Carson City of its hard cases rather than die in bed in laudanum-addled agony.

Over the decades since, the novel has come to be voted by the Western Writers of America one of the Ten Best Western novels written in the 20th century, and film historians consider The Shootist to be one of John Wayne’s five best westerns. I was privileged to work on that screenplay and receive a Writers Guild nomination for Best Adaptation in 1976. Film critic and historian Arthur Knight wrote, “Just when it seemed the Western was an endangered species ... Wayne and [director Don] Siegel have managed to validate it once more. It’s a film to remember.” And indeed it has been.

Motion pictures are generally plot-driven, and Glendon took great care with his story lines in a variety of genres, from a time period-jumping mystery (Skeletons), to a period romance (Loveland), to a contemporary romantic comedy (Pinch Me, I Must Be Dreaming), to a comic western about the last misadventures of Bat Masterson and Wyatt Earp (The Old Colts), to a dramatic tragedy (Welcome to Thebes). His favorite British publisher, Tom Rosenthal, felt Glendon had “the widest literary range of any American novelist of his era.” Bless the Beasts & Children, a young adult novel that advocates for animal rights — and was made into a 1971 film directed by Stanley Kramer featuring an eponymous song by The Carpenters — seals that judgment.

In theaters this fall is Glendon’s ninth filmed story and last western, The Homesman. It is an extraordinary tale — and an unusual female-oriented one at that — about a mismatched frontier couple’s long journey escorting four women back across the Missouri River to civilization, where it is hoped they can receive medical care from their Eastern relatives after being driven mad by a hard winter on the Great Plains in the 1850s. Kirkus Reviews called it “one of Swarthout’s best westerns ... an absorbing western epic of endurance,” while the Associated Press review stated “Glendon Swarthout has honed writing excellence to a nearly unsurpassable level,” calling it “a powerful novel” and “a classic of vivid realism and gripping storytelling.” The book swept the western genre awards in the late 1980s, winning both the Western Heritage Award for Best Western Novel from the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum and the Spur Award for Novel of the West from the Western Writers of America.

Glendon’s novel-to-film sale ratio was phenomenal — of his 16 published novels, seven have been made into films. Two short stories have also been adapted for the big screen, and many other stories and novels have been optioned, some several times over. I believe this cross-media success was due in part to his writing philosophy. Creative writing courses in universities often emphasize character over plot in writing fiction, but professor Swarthout disagreed. “Give me a really good story,” my father would say, “and I guarantee you the characters will show up to execute it.”

He would undertake extensive research, developing detailed story outlines and character sketches that often ran over a hundred pages. The results are strong, linear stories — without the need for superfluous flashbacks or interior monologues — that lend themselves well to film.

My father lived his dream of being a professional writer, and he became the absolute master of the western. Yet his career is all the more amazing considering the man. He was a college literature professor who grew up in a rural farming town in Michigan, never rode a horse, and never owned a Stetson — or even a pair of cowboy boots. But he sure knew how to tell a story.

Miles Swarthout’s first western novel, which was based on one of his father’s Saturday Evening Post short stories, The Sergeant’s Lady (Forge Books, 2003), won a Spur Award for Best First Novel.

Photography: Courtesy Miles Swarthout

From the November/December 2014 issue.