The year was 1912. The Summer Olympics were in Stockholm. Jim Thorpe was poised to go down in history.

Stockholm

The decathlon was held over three days, from Saturday, July 13, to Monday, July 15. Three events the first day, four the second, three the third. Jim had already competed in two individual events by then as a means of warming up for the decathlon, finishing strongly through out of medal range in the high jump and long jump. The first day for the decathlon brought the foulest weather of the games, a persistent rain that rendered the track slippery, the footing in the throwing rings tentative, the infield landing pits sticky with mud. Pop Warner came to the stadium anxious that morning, knowing from experience with his star athlete on the football field that Jim did not like to perform in bad weather. Jim was less concerned. “At no time during the competitions was I worried or nervous as to the outcome,” he said later. “I had trained well and hard and had confidence in my ability. I felt that I would win.”

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Hulton Archive

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Hulton Archive

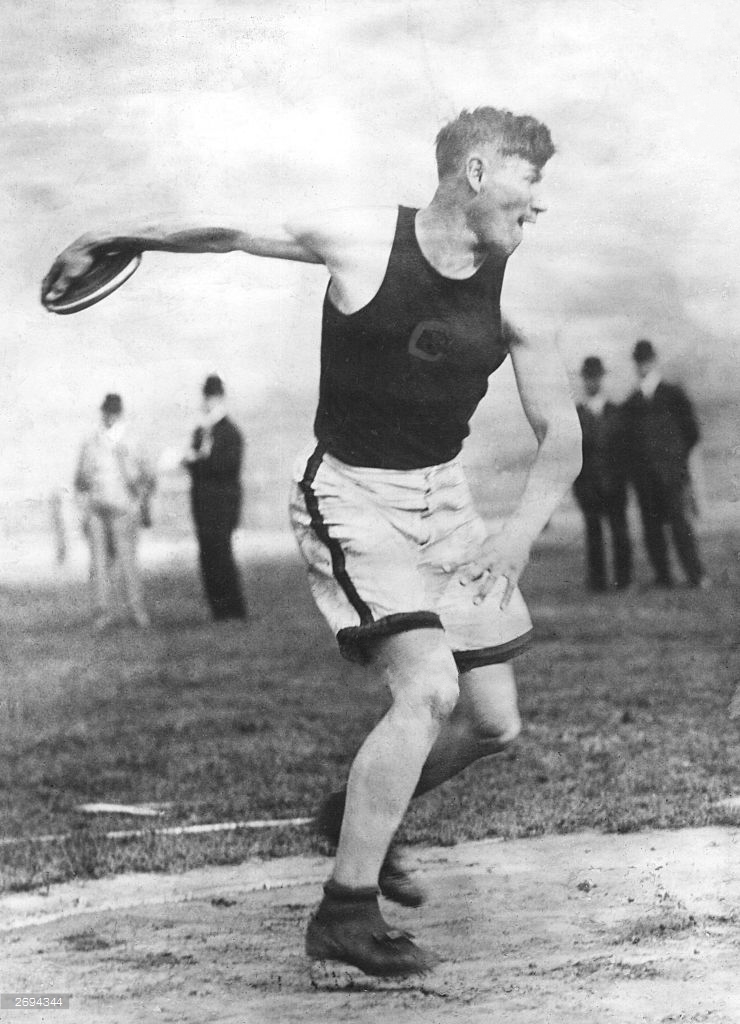

At the start, there were 29 all-around athletes in the decathlon field, so many that for the first event—the 100-meter dash—the runners were divided into 10 heats, each running against only two competitors. Thorpe finished second in his heat, but with a time of 11.2 seconds that put him tied for third place overall. As rain fell harder, spectators fled for shelter beneath overhands and tower exits, and a panoramic bloom of umbrellas protected those who remained in their seats. The athletes loitered in the drenched infield until the downpour subsided, then moved on to the next event, the running broad jump, where Pop Warner’s fears about Jim underperforming in bad weather were almost realized. The slick push-off boards made him foul on his first two jumps, but his third and final attempt was clean if not spectacular, and his 22.3 feet was good enough for third in that event, leaving him in second place overall.

Before the next event, the shot put, Jim dashed into the locker room and switched from his drenched outfit to a dry warm-up suit. In that era, there were two shot competitions, two-hand (meaning first right, then left) and best-hand. The decathlon was best-hand only. This was where Thorpe began to separate himself. Though several competitors brought more bulk to the ring, none brought more coiled strength, and Jim won easily, topping his nearest competitor by nearly three feet, sending him into first place overall after the first day. Changing clothes was the key, he said to Pop in the dressing room later. The dry uniform helped him win. Citius, Altius, Fortius was the Olympic motto—“Faster, Higher, Stronger.” Thorpe, after day one, was faster, longer, and stronger.

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of International Olympic Committee

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of International Olympic Committee

Day two of the decathlon, Sunday, July 14, broke clean and bright, the rains gone. The field was now down to 23, with six competitors already dropping out. As he prepared for the first event that morning, the high jump, Jim had a problem. “I couldn’t find my pet shoes,” he recalled. What happened to them was unclear. He thought someone either stole them or went off with them accidentally. Perhaps he’d misplaced them himself. He and Pop reacted quickly, rounding up a pair of mismatched shoes. They were ill-fitting, different sized, different laces. Here is where Warner’s many hours fiddling with equipment at the Carlisle shop proved invaluable. He jury-rigged temporary cleats and padded the heels and dent Jim into the stadium infield looking from the shins down like a ragtag interloper. The left shoe looked nothing like the right shoe, and he wore two socks on his left foot, a white sock over a black one, and a shorter, thicker sock on his right foot.

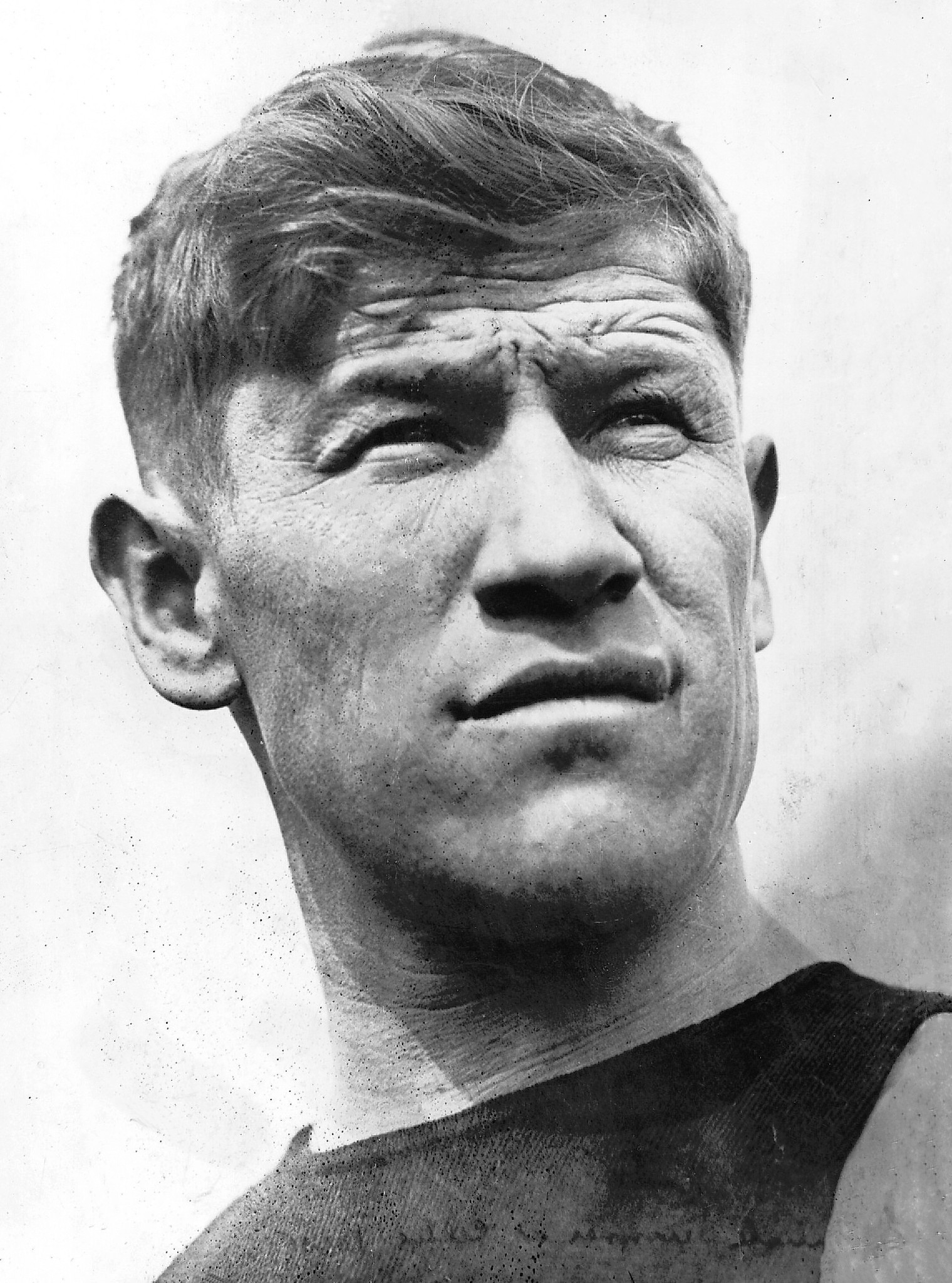

And then he went out and won the high jump, clearing the bar at six feet and one inch. A stunning photograph was taken of Jim standing on the stadium infield then. At first the viewer is drawn to the odd mix of sock and shoes, but soon the eyes move up to see his relaxed stance, hands on hips, left foot slightly forward, and then the majesty of his rugged face. Here is the beauty that poet Marianne Moore captured so well when she was his teacher back at Carlisle—Thorpe’s “equilibrium with no stricture … the epitome of concentration, wary, with an effect of plenty in reserve.” Now he was Altius, and after only four events seemed uncatchable, so far ahead that all he had to do was finish in the top six in the remaining events. …

With the field down to 12 for the 1,500 meters Thorpe held a substantial lead that the only way he could lose was if he withdrew. Instead, he ran. There were three heats, four men each. As the Olympic Games of Stockholm 1912 Official Report described: “The third and last heat was Thorpe’s, who ran the distance as good as alone, the rest of the field being a long way behind the leader.” His time was the best of all the heats, 4 minutes 40.1 seconds. It could be said that Thorpe performed the entire decathlon as good as alone, the field being so far behind. Olympic officials, spectators, fellow athletes—all were stunned by what they had witnessed. “As Thorpe went from one strenuous event to another, never seeming to feel fatigue, the wonder and admiration of the onlooking athletes found expression in what came to be a stock phrase, ‘Isn’t he a horse!’” Pop Warner later recalled, Thorpe finished 700 points ahead of the nearest competitor with 8,412 points, a record score. With that win, Jim had provided the United Stated with six points, and when added with Lewis Tewanima’s two points for the silver in the 10,000, Pop Warner’s boys from the Carlisle Indian Industrial School—two athlete who were not recognized as citizens—provided more points for America than any other educational institution.

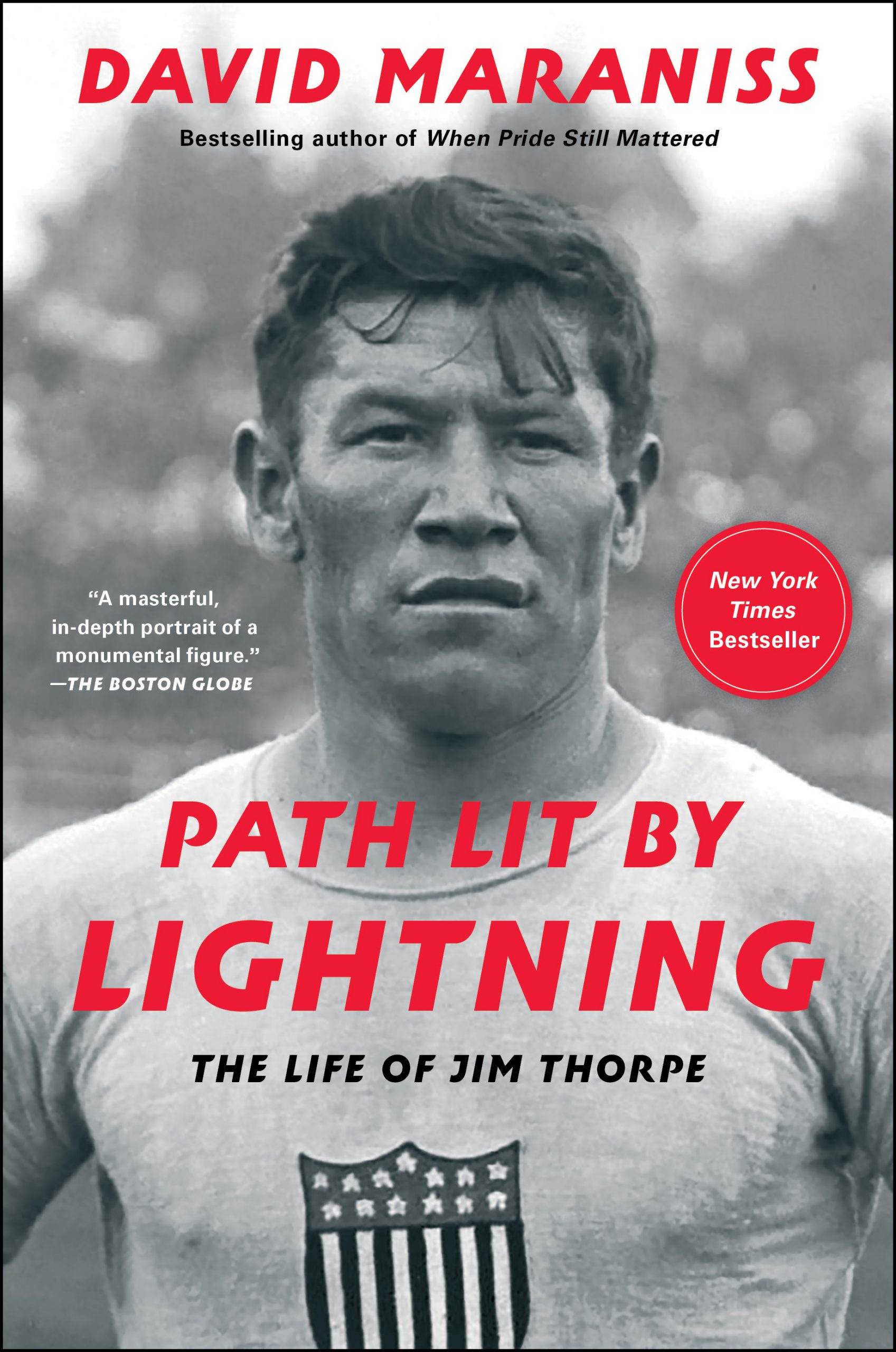

Excerpted from Path Lit by Lightning: The Life of Jim Thorpe, by David Maraniss, Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2022. Used by permission.

Excerpted from Path Lit by Lightning: The Life of Jim Thorpe, by David Maraniss, Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2022. Used by permission.