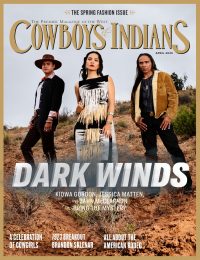

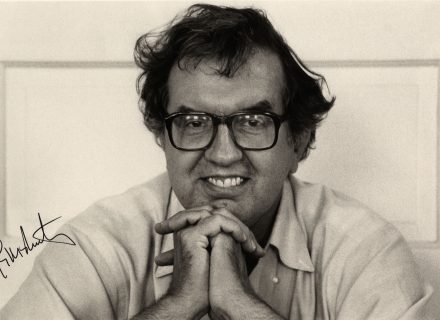

A new collection of essays written in tribute to Texas literary giant Larry McMurtry begins with a moving foreword by lauded author Stephen Graham Jones.

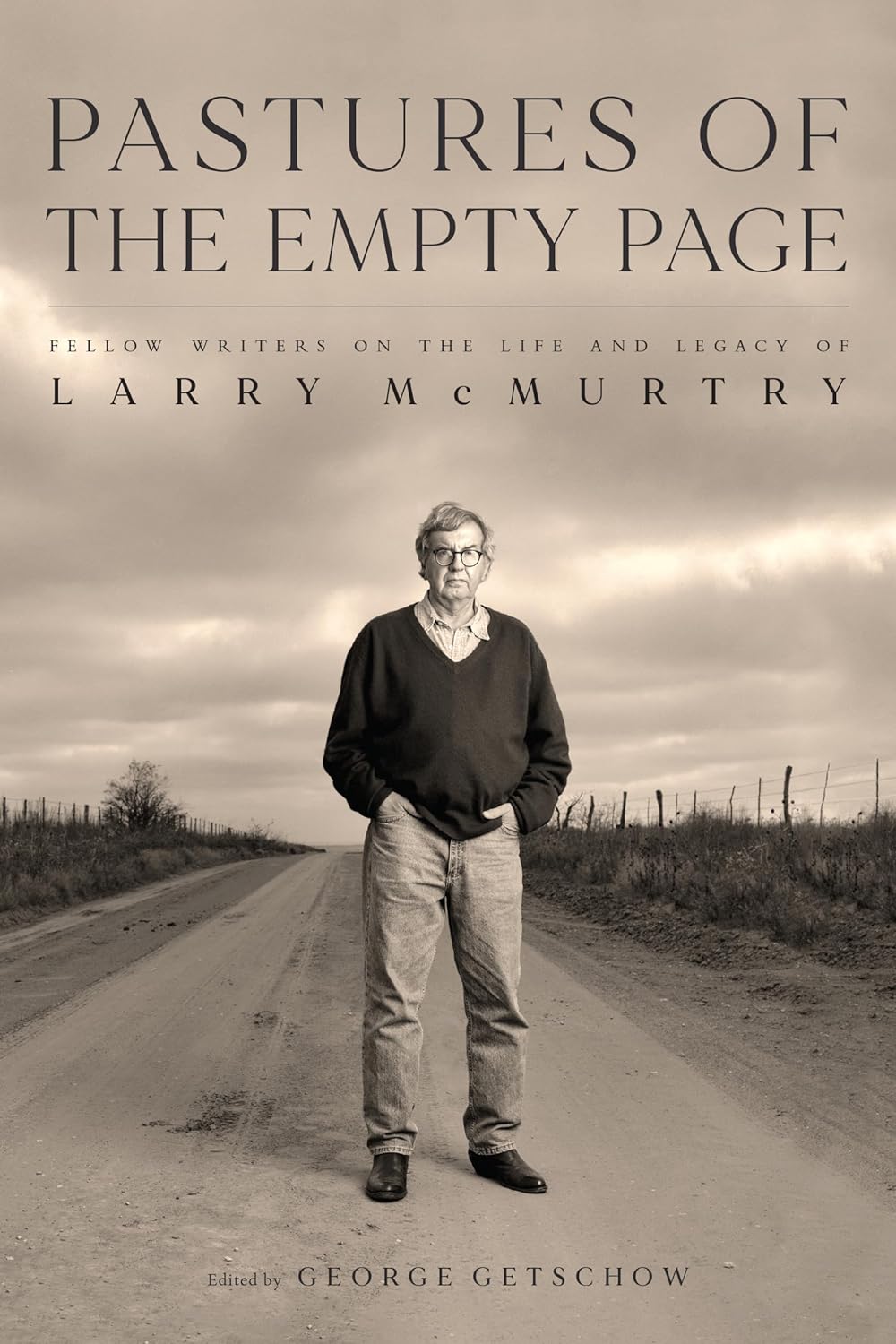

The new book Pastures of the Empty Page: Fellow Writers on the Life and Legacy of Larry McMurtry came together out of respect and admiration for the Lonesome Dove author, who died at age 84 on March 25, 2021, of congestive heart failure in Tucson, Arizona. Sales of the collection of tribute essays will help fund the nonprofit foundation Archer City Writers Workshop: A Living Legacy to Larry McMurtry.

Here, we excerpt the foreword by acclaimed author Stephen Graham Jones.

“Sam the Lion.”

Every time I start a new novel, I say this to myself. It’s a reminder. What it tells me is that this world I’m about to start creating, that I’m already dreaming up, it’s not shiny and new, it’s not created from nothing. No, if it’s to be real, if it’s to be something the reader can engage with, invest in, live in, believe in, then it has to have a past. Like Sam the Lion.

A lot of readers find Holden Caulfield at that important part of their lives. Or Jude the Obscure.

I found The Last Picture Show.

At the time, I was still living those Friday nights Larry McMurtry talks about. Friday nights with nothing to do in the vast nothing of West Texas.

In his later years, Louis L’Amour would talk about what he called “the Yondering.” It’s that restlessness to head out, your saddlebags slung over your shoulder, your boots down at heel, maybe two dimes and a nickel in your pocket.

That yondering is what so many of Larry McMurtry’s books are made of. It’s what I connect with in his stories, his characters — I want to say “his worlds,” but, really? The Texas he wrote about so much, it’s the same Texas that’s in me, and that I’m pretty sure is in all the writers in these pages, each of whom also feels a connection to Larry McMurtry, or owes him a debt, or just wants to pay homage with the best thing they have: their words.

As for me, after seeing “the Yondering” and my Texas in The Last Picture Show, man, I was hooked. There was Horseman, Pass By, which I could never understand why he disowned. Lonesome Dove, of course, and its sequel that had no right to be so good — has any sequel ever stood on its own as well as Streets of Laredo?

And on and on down the bookshelf and into television and film … if there was a story that Larry McMurtry couldn’t tell and tell well, then I haven’t heard of it.

He came at fiction in a way we don’t get to read very much. He was dismissive of attempts to intellectualize his work, to drag it into the academy — counting on that for validation is never the best bet — but what he was doing wasn’t the kind of commercial we used to see on spinner racks, either.

I think Larry McMurtry just wanted to tell a good story, and to hell with people who wanted him to be part of this movement or that era, and to hell with genre distinctions as well. I can imagine him saying that if it works, it works, so what’s all the blather about?

That doesn’t mean you can’t learn from him, though. What I learned was “Sam the Lion.” After reading about Sam, and how he used to be before The Last Picture Show, I found myself considering my uncles and great-uncles differently. I wondered what untold stories their pasts held. Because they hadn’t always been like they were now.

So?

So I started hanging around, listening to the lies they would tell about being young, and when I could keep myself from believing in them all the way, I could sometimes get the briefest glimmer of the way it actually might have been. And I could guess at why they were telling this story this way now, not some other way.

They became people, I’m saying. Broken and wonderful, hurt and proud, and moving still, in spite of what they were dragging behind them.

Every time I sit down to write something, I remind myself of this — that these characters have been shaped by their experiences. And that just because they’re not spouting those experiences, it doesn’t mean the past isn’t there all the same.

In graduate school, in a class on Robert Browning, the professor slowed a poem down to show us the grime and rust on a roomful of implements, grime and rust that meant this room had existed for decades before the story walked into it.

I already knew that, though.

I’d come up reading Larry McMurtry, I mean.

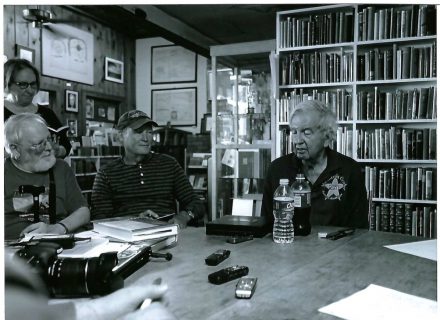

Even more than that, the year before I read that Robert Browning poem, I’d trekked over to Archer City to catch a glimpse of Larry McMurtry.

I was in Denton at the time, attending the University of North Texas, and my wife had to pack me a cold lunch because we didn’t have money for me to be stopping anywhere to eat, but I saw him.

For many of the writers in this collection, that won’t be a big thing. Larry McMurtry was in the world, he was available to see, maybe even to talk to, or to sit at a table with.

Not to me, though.

To me at twenty-three, he was made of Other Stuff. He was some higher order.

Word was, back then, that the downtown of Archer City, which he’d turned into a sprawling bookstore, would sometimes be haunted by him. That if you hung around long enough, you might could see him.

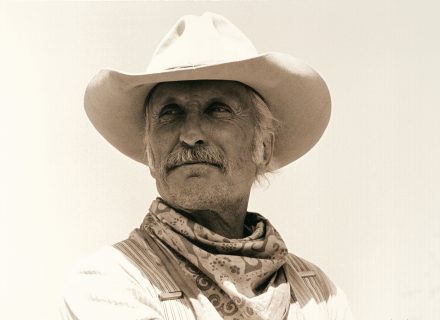

I cruised the science fiction, I cruised the thrillers, I ran my fingers down the spines of row after row of books, some of them probably by the people in this book you’re holding, and then, finally, way down at the end of one aisle, there he was.

He was guiding a book dolly, and he stopped for a moment like he’d sensed me. What I told myself was that we were making a connection. I was writing fiction by then, and knew I was destined to reach the same literary heights he already had, so I imagined a taut string of awareness connecting the two of us.

It is grandiose, yeah. Is there any other way to think when you’re twenty-three, though? If you don’t think like that, then the world swallows you. Thinking like that’s self-defense, almost.

So he looked up, Mr. McMurtry looked up. Larry McMurtry looked right down the heart of that aisle and into my future, and what I thought then, what I want to have been true, was that he could see me now, twenty-six years later, still looking back at him, and holding my breath, trying to make the moment last, to never have it end.

Thank you, sir.

I’m still in your bookstore. All of us listed in the table of contents, we’re bunched down at the end of that aisle, and we don’t really want to leave. Even after you nod once, push your book dolly back into the shadows, we’re still looking into the space you just filled.

It’s filled yet.

Stephen Graham Jones is the Ivena Baldwin Professor of English, as well as a Professor of Distinction, at the University of Colorado Boulder. He is the author of more than 25 books, including The Only Good Indians and My Heart Is a Chainsaw. Jones has been an NEA Fellow and a Texas Writers League Fellow. He won the Texas Institute of Letters Award for Fiction, the Independent Publishers Multicultural Award, the Bram Stoker Award, four This Is Horror Awards, and he was a Shirley Jackson Award finalist and a Colorado Book Award finalist.

Excerpted from Pastures of the Empty Page: Fellow Writers on the Life and Legacy of Larry McMurtry, edited by George Getschow © 2023, published with permission from the editor.

Pastures of the Empty Page: Fellow Writers on the Life and Legacy of Larry McMurtry is available from University of Texas Press. Out respect for Larry McMurtry and his remarkable body of work, the contributors to the essay collection are dedicating royalties from the sale of the book to a nonprofit foundation called the Archer City Writers Workshop: A Living Legacy to Larry McMurtry. The purpose of the foundation is to create a permanent writing center in Archer City for students and professional writers who hope to channel McMurtry as their muse.