Frank Eaton, aka Pistol Pete, shot his way into the legends of Oklahoma and the lore of the West.

The scene was pure Americana. Four desperadoes hold their horses still waiting to see what the lone lawman blocking their escape will do. Words are exchanged. Suddenly the lone lawman shouts out, “Fill your hand, you son of a bitch!” as he charges into the outlaws, firing his pistols while holding the horse’s reins in his mouth.

It is the most famous scene in Charles Portis’ 1968 novel True Grit. The quote and the incident, though, were pure Pistol Pete (aka Frank Eaton), documented in his 1952 autobiography. Instead of a fat one-eyed marshal, it was a young Eaton with his long hair in braids, bringing rustlers to a reckoning in a meadow near Webbers Falls, Oklahoma.

Born in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1860, Frank Boardman Eaton would begin his transformation into Pistol Pete at age 8. That was when the Ferber-Campsey gang rode up to his family’s farmhouse in Kansas calling out his father. When the elder Eaton opened the door, they shot him dead in the moonlight. Mose Beaman, his father’s friend and neighbor, is said to have told young Frank, “My boy, may an old man’s curse rest upon you, if you do not try to avenge your father.” Beaman gave him his first gun, an old Navy revolver, and taught him how to handle it. Three days after his father’s funeral, Frank was already practicing with the pistol, bent on revenge.

His mother remarried, and the family moved to a homestead just south of modern-day Bartlesville, Oklahoma, in the Cherokee Nation. A teenage Frank began earning a reputation for his shooting ability in weekend contests with neighboring Cherokees. To improve his skills with a gun, he traveled to Fort Gibson. There he outshot U.S. soldiers in every shooting match — to the point that the commanding officer dubbed him Pistol Pete. The nickname stuck, and his reputation got around.

Eaton couldn’t have known it at the time, but the long-awaited showdown pitting him against his father’s killers was soon to unfold. And it would take place in the Cherokee Nation.

The remote Indian Territory had long been a safe haven for criminals from bordering states. White outlaws not only took refuge in the thinly populated Cherokee Nation, they took cattle and horses. But the local law, the Cherokee Lighthorsemen, were hesitant to act: Since the Goingsnake Massacre in 1872, all Cherokees had shied away from shootouts with whites. In that incident, in the Goingsnake District of the Cherokee Nation, the trial of Ezekiel Proctor — who was accused of shooting and killing Polly Beck — erupted into a shootout in the courtroom. In the bloody tragedy, eight U.S. deputy marshals as well as three Cherokees were killed. Cherokee authorities granted amnesty to the Cherokees who had done the shooting. The affair had damaged relations with the federal government, and Cherokees wanted the matter to heal.

When the Cherokees discovered the Campseys and Ferbers were rustling cattle, they felt young Frank Eaton, Pistol Pete, might be a solution. They guided him to Ferber and Campsey’s hide-outs, where Eaton took on his father’s murderers one at a time. He killed both Doc Ferber and a Campsey in the same gunfight by himself. Wyley Campsey had escaped Eaton’s wrath, riding west. Pistol Pete was only 16.

The Cherokees were impressed. Famed Cherokee Captain of the Lighthorse, Sam Sixkiller, took young Frank under his wing and taught him how to read men. Pistol Pete began hunting men for Judge Isaac Parker, “the hanging judge,” out of Fort Smith, Arkansas. (Records show he rode for Judge Parker, but his status is marked as “unclear.”) Frank liked to boast that by age 17 he was the youngest U.S. deputy marshal in history. “When I rode for Parker,” Eaton wrote in his autobiography, “some 65 officers were killed.” One of them was Capt. Sixkiller, gunned down in an ambush in Muskogee, Oklahoma.

Eaton eventually became a cattle detective and began seeing a woman named Jennie. When Eaton was ordered to Texas, Jennie placed a large crucifix around his neck. During a running shootout with rustlers outside of Fort Worth, the cross caught a bullet that would have killed Eaton. Hurrying back to propose, he found Jennie had just passed away from pneumonia.

Revenge trumped tragedy when word came that Wyley Campsey had a saloon in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Eaton made his way there and one fateful night walked through the saloon doors to confront the last of his father’s killers. Flanked by his two gunmen, Campsey stood before Pistol Pete telling the kid how foolish he was. Eaton interrupted, “I am not here to talk.” Five shots echoed against the walls of the small saloon. Three men lay on the sawdust floor, but only a badly wounded Eaton was alive.

The Old West now had a saying, “hotter than Pete’s pistol,” but the legendary figure was finished with the vengeance trail. He obtained a farm during the 1889 Oklahoma Land Rush outside of Perkins at age 29. He married twice and had 10 children before he died in 1958 at age 98.

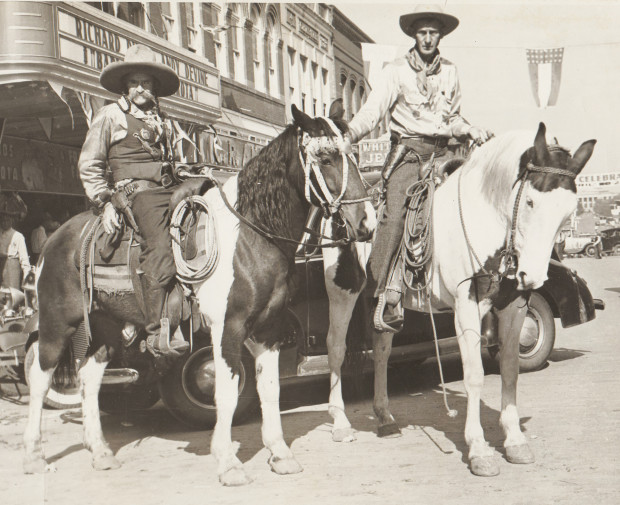

In 1923, the sight of Pistol Pete riding in the Armistice Day Parade in Stillwater, Oklahoma, gave Oklahoma A&M (now Oklahoma State University) students the idea of using his image as the school’s symbol. Today, the heavily mustachioed cowboy modeled after Pistol Pete is the mascot for OSU, the University of Wyoming, and New Mexico State University — a symbol of the enduring West. The living cowboy mascots modeled after him are the public part of the Pistol Pete picture. For a more private impression of the man, visit the Frank Eaton Historic Home in Perkins, Oklahoma, where Frank lived with wife Anna from 1929 until 1958 and where he wrote a colorful column called Pistol Pete Says for The Perkins Journal. Originally at 119 E. Chantry St., the restored house was moved in 2008 to its current location at 750 N. Main St. on the Oklahoma Territorial Plaza.

From the July 2015 issue.