As the old song goes, "Open up that Golden Gate!" We're heading to the Golden State for some C&I-style good times.

Marin County

Where: Just north of the Golden Gate Bridge

Don’t Miss: “The best tree-lovers monument that could possibly be found in all the forests of the world”

Don’t just gaze at the Golden Gate. Cross it. That’s certainly what entrepreneurial sorts had in mind when they took in the narrow 335-foot-deep strait at the mouth of the San Francisco Bay and decided there needed to be a better way to get from the north end of the San Francisco Peninsula across to the southern end of Marin County on their way to the gold fields beyond. Though the idea for the bridge goes as far back as 1869, construction didn’t start till 1933 and wasn’t finished till 1937. You can walk across for the best in windblown scenic experiences, but a car gives you the freedom to explore the other side, where some of the true wonders of Northern California await, such as Muir Woods, one of President Teddy Roosevelt’s lesser-known acts of conservation. He used the powers of the Antiquities Act of 1906 to make Muir Woods a national monument, wanting to name it after William Kent, who donated nearly 300 acres of coastal redwoods to make sure they were protected. But Kent and wife Elizabeth wanted the forest to be named for the great conservationist John Muir instead. On learning of it, Muir is said to have exclaimed, “This is the best tree-lovers monument that could possibly be found in all the forests of the world.”

The Mission Trail

Where: 600 miles, along El Camino Real, the “Royal Road”

Highlight: Mission Santa Barbara, “Queen of the Missions”

You could make it your life’s mission to see all the Spanish missions in California — that’s how picturesque and historic they are. There are 21 of these gems in “Alta” California, built between 1769 and 1823 (along with four forts, or presidios). Stretching along the coast from San Diego in the south to Sonoma in the north, they were the frontier outposts of Spain. When the first, Mission Basilica San Diego de Alcalá, was built, the Declaration of Independence was still seven years away from being inked.

Try to imagine the great landmass that would become the United States, under British control in the East and Spanish in the West. While the Redcoats and Revolutionaries were coming to muskets and rifles in the 13 colonies, on the other coast, the Spanish king was dispatching military troops and Franciscan missionaries to both colonize what would become California and Christianize its indigenous peoples.

The cities of Santa Barbara, San Diego, San Francisco, San Jose, and a half-dozen others with Spanish saint names would eventually grow up where missions were planted by Franciscan friars Junípero Serra and Fermín Francisco de Lasuén. The critical question of whether the system was “salvation or slavery” aside, the missions were important frontier institutions, and each has its Catholic colonial charms and unique history.

Our favorite? Old Mission Santa Barbara, the “Queen of the Missions,” which rises in elegant sandstone against a Santa Ynez Mountains backdrop. Local Chumash Indians, superb basket makers with their own monetary system, lived and worked on the grounds, becoming farmers and herdsmen to the mission’s many cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, mules, and horses.

Tours can be had of Mission Santa Barbara’s 10 acres of beautifully landscaped grounds and gardens, the lovely church, historic cemetery, and museum. Seeing it all, you can try to imagine hearing it, too — what it must have been like when Chumash ensembles played European violins, woodwinds, and brass instruments, and Indian choirs sang.

Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail

Where: Throughout California

Raise a Glass: Toast Juan Bautista de Anza’s legendary expedition at Arguello, a new restaurant in the Presidio’s historic Officer’s Club

Charged with exploring Las Californias and establishing a Spanish colony in what is now the Bay Area, the 18th-century commander in New Spain Juan Bautista de Anza embarked with the call, “¡Vayan Subiendo! ” (“Everyone mount up!”) on October 23, 1775, with second-in-command José Joaquin Moraga, Father Pedro Font, a party of more than 240 men, women, and children — military and nonmilitary families, Indian guides, vaqueros, mulateers,

servants — and 1,000 head of horses, cattle, and mules.

The 1,200-mile national historic trail that commemorates Anza’s 1775 – 76 expedition — from Tubac Presidio, near present-day Tucson, across Arizona, along what is now the California-Mexico border, and up through what was then Alta (as opposed to Baja) California — immerses you in California history, geography, flora, and fauna. You can drive it or hike it, appreciating all that is the Golden State in places like the Upper Virgenes Canyon Open Space Preserve — once the 2,983-acre Ahmanson Ranch and now one of the last undeveloped areas in Southern California — and Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, where, in December of 1775, Anza’s historic expedition traveled up Coyote Canyon, watered and pastured their animals, and recovered from a leg of their epic journey.

In the Bay Area town of Martinez, Anza’s expedition intersects with the life of the Scottish father of the U.S. national park system, John Muir, whose influential exploration and advocacy of wilderness throughout California make him a hallowed figure in the state. Muir lived here from 1880 until his death in 1914. His home, now a fascinating museum, is part of the John Muir National Historic Site, where you’ll also find the Anza Trail Exhibit housed in the 1849 Martinez Adobe.

But it’s across the bay in San Francisco that Anza’s story reaches its climax. In 1776, with his colonists deposited for the time being in Monterey to the south, Anza, Lt. Moraga, and Father Font headed out to choose sites for a presidio and the mission that would become Misión San Francisco de Asís/Mission Dolores, the sixth in the chain. They found their ideal location at the north end of the San Francisco Peninsula. On seeing it, Father Font took in the bounty and beauty of the empty landscape and prophetically imagined a future city that would be one of the most glorious in the world.

Indian Canyons

Where: Agua Caliente Indian Reservation, Palm Springs

Featuring: World’s Largest California Fan Palm Oasis

Many moons before Gene Autry Trail and Bob Hope Drive were etched onto the Palm Springs grid, ancestors of the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians made their own inroads in what would become SoCal’s fabled desert oasis. Specifically at Indian Canyons, a Shangri-La of surprisingly lush backcountry hiding less than 5 miles south of town.

The Native American-owned and -operated preserve features a trio of picturesque snowmelt-rich canyons laced with walking trails, natural springs, and vestiges of ancient everyday life left behind by the area’s original native inhabitants — an area the Spanish called la palma de la mano de Dios, “the palm of God’s hand.”

Today, a Trading Post gift shop marks the entrance to Palm Canyon, the real hiking crowd-pleaser here. Home to the world’s largest grove of California Fan Palms, the dense forest of tall frond-skirted palms really is an amazing sight — and an impressive example of California’s only native palm in its native environment, unlike the imports that grow in lanky rows on the beach or like emaciated loners beside Los Angeles freeways. “They’re actually not trees at all, but a rather large member of the grass family,” one ranger recently clarified at the trailhead.

NoCal footnote: An equally vital off-the-beaten-path Native-operated canyon hides about a dozen miles south of Hollister at Indian Canyon — in one of the few patches of federally recognized “Indian Country” on the California coast.

Teeming with birds and canopies of cottonwoods, oak, and sycamore, the Ohlone-held site is furnished with sweat lodges, a round house, and quiet arbor areas open to all indigenous populations for ceremonial use. The general public is welcome to visit as well, by appointment and during the 19th annual Indian Canyon Storytelling and Indigenous Gathering on July 11, when the place will resonate even more than usual with the rich cultures and histories of Native California.

Wyatt Earp's Gravesite

Where: Hills of Eternity Memorial Park, Colma

Trivia Bullet: Founded as a necropolis, the town of Colma (pop. 1,479) dedicates more than 75 percent of its land to cemeteries, with the dead outnumbering the living by more than 1,000 to 1

Impulsive gambler. Unscrupulous saloonkeeper. Itinerant fortune chaser. Occasional swindler. Uncanny bullet dodger. Shameless tall tale teller and Hollywood fame seeker. Wyatt Earp (1848 – 1929) was reputedly all of that, and plenty of other things to boot — including world’s most unlikely guy to reach octogenarianhood. But that doesn’t mean you can’t still pay respects to the most enduring name in Old West, uh, law enforcement, however ambiguous or arbitrary the title may be.

By all accounts, Wyatt was also a loving husband to his wife, Josephine, who interred his ashes in a quiet Jewish plot (in keeping with her family faith) in cemetery-suffused Colma. Josephine would join him 15 years later. Only here — and not in Tombstone (the place or the movie) — can one sum up the 50 shades of Wyatt Earp with a simple epitaph: “... That nothing’s so sacred as honor, and nothing so loyal as love!”

Coronado

Where: Across the bay from San Diego

Gotta Do It: Sunday brunch in the Crown Room at the landmark Hotel del Coronado

Like many Golden State gambles, California’s most illustrious resort peninsula began with a dreamy idea. In 1885, a pair of businessmen dropped $110,000 on a sunny, vacant thread of land hiding on the far side of San Diego Bay, where the Kumeyaay Indians lived seasonally, hunting quail and enormous rabbits, fishing for sea bass large enough to feed the tribe for a month, and collecting abalone and lobster in the tide pools.

Maps were drawn. Cheap labor was barged in. Lots were sold to raise more cash. Ground was broken on the Hotel del Coronado — the world’s largest resort hotel at the time — which welcomed its first guests, amazingly, within the following year.

Coronado’s first wave of privileged vacationers were adventure-seeking Victorian aristocrats journeying by train and rail car from back east — a seven-day trip, each way. Then came the 20th-century’s who’s-who guest list of Hollywood A-listers, dignitaries, and American presidents.

Today, the nicknamed “Crown City” (Coronado is Spanish for “crowned one”) and its iconic hotel are the Golden State’s quickest transition from urban grit to small-town seaside charm. Crossing the dramatic boomerang-shaped San Diego-Coronado Bridge from downtown San Diego onto the picturesque blocks of Coronado’s Orange Avenue (once lined with orange trees, now with flowers, topiaries, restored classical-revival-style buildings, and window-shoppers) plants you in one of the country’s most storied and successfully revived coastal resort communities.

Will Rogers State Historic Park

Where: Pacific Palisades, Los Angeles

Double Your Pleasure: On a tour of Will Rogers’ home and horseback ride through his rugged “backyard”

Will Rogers was at home everywhere. On the screen, stage, page, airwaves, and in most American living rooms throughout the 1920s and 1930s until his untimely death. But the legendary cowboy humorist was comfiest at his 31-room family house on his 186.5-acre ranch nestled between the ocean and mountains of coastal Los Angeles.

Back in the day, Rogers and buddies like Walt Disney, David Niven, and Gary Cooper mounted their horses and galloped around the estate’s fabled near-regulation-size polo field before retreating to the nearby Beverly Hills Hotel’s Polo Lounge for grub — which is supposedly how the place got its name. Players and spectators still gather at Rogers’ old digs for weekend games, but the real prize at this beautiful park — granted to the state by Will’s widow, Betty, in 1944 — is a tour through the rest of the grounds.

Start at the old ranch house, where docent-led tours show off the humorist’s quirky, decidedly Western decorative tastes. Then take a guided horseback ride through the park’s extensive trail system, or a hike up to Inspiration Point, enjoying the same immortal views prized by one of the West’s most beloved icons.

Alcatraz

Where: San Francisco Bay

Look Up: The infamous graffiti from 1969 is still visible on the water tower

Say “Alcatraz” and people think penitentiary, not pelicans. But upon seeing that rocky protuberance, Spanish explorer Juan Manuel de Ayala, the first European to navigate San Francisco Bay, named it la Isla de los Alcatraces, “the Island of the Pelicans.” Twenty-two rugged acres topped with a lighthouse (the original, lit in 1854 to facilitate the Gold Rush, was the first on the West Coast), there’s a lot more to Alcatraz than notorious criminality.

As compelling as it looks 1½ miles offshore, ironically, it’s Alcatraz that has the great view: across the bay with its hazardous (escape-deterring) currents, to a sweeping panorama of the San Francisco skyline. Not that Al Capone, George “Machine Gun” Kelly, James “Whitey” Bulger, Robert “Birdman of Alcatraz” Stroud, and the hundreds of other bad boys incarcerated on “The Rock” during its federal pen years from 1933 to 1963 were appreciating the vista when they were doing pushups in the yard.

Centuries before maximum-security convicts did hard time at Alcatraz, members of the Ohlone Tribe — who today call themselves Muwekma, or “the people” — fished, hunted sea mammals, gathered bird eggs, left prayer sticks and offerings, and perhaps used the island to hide from the Spanish military while fleeing the missions. Centuries later, in a bold action that would inspire the American Indian Movement, Native activists seized the place on Thanksgiving Day in 1969 and declared Alcatraz Indian land, as graffiti from their famous 19-month occupation still attests today.

Native presence — and mistreatment — at Alcatraz goes way back. “Paiute Tom” became the first American Indian prisoner in 1873, but it was the plight of the Hopi 19, punished here in 1895 for resisting the government’s attempts to force Hopi children into distant boarding schools, that would go down in history as an emblematic injustice.

Today you can ferry over and tour the iconic penitentiary, which is now a national park. Don’t forget to look up at the water tower: When it was restabilized in 2012, much of the historic graffiti from the 1969 occupation was destroyed, so the Park Service invited the daughter and grandson of Mohawk activist Richard Oakes to replace it. The message is still proclaimed: Welcome to Indian Land — Home of the Free.

Bishop

Where: Owens Valley, Eastern Sierra Nevada Mountains

Pack It Up: At the annual Bishop Mule Days Celebration

It’s a place you might just pass through on U.S. Highway 395 on your way to the phenomenal skiing and snowboarding at Mammoth Mountain, the fantastic trout fishing at Convict Lake, or the rugged two-wheeling at Mammoth Mountain Bike Park (named No. 1 bike park by Outside magazine in 2013). But if you’re in Bishop over Memorial Day Weekend (May 24 – 29, 2016), you can be among the 30,000 fans, 700 mules, and their trainers, riders, and packers getting packing season underway at the annual Bishop Mule Days Celebration.

Any Old West miner or backcountry explorer could have told you how indispensable the mule — with its strong back and sure feet — was to Western expansion and the growth of California. How best to honor that curious cross between a male donkey and a female horse today? With 181 events, including mule shows, skills competitions, barbecues, parades, country music concerts, dances, and the crowd-pleasing and crazy “Packer’s Scramble.”

While you’re in Bishop, be sure to pick up some sheepherder’s bread at Erick Schat’s Bakkerÿ, where they’ve been baking the hearty stuff in stone hearths since 1907. Stash a loaf in your saddlebag and arrange for a pack trip into the rugged and breathtaking Eastern Sierra backcountry. Numerous pack stations and outfitters in the area are at the ready to design whatever kind of outing suits your Western fancy — mule or no.

Point Reyes National Seashore

Where: Marin County Coast

Coolest Camping Experience: A night on the coast at Wildcat Camp and a morning walk

along the beach to nearby Alamere Falls

One would naturally expect a crowd at Point Reyes. Nestled between the hills of Marin and the crashing Pacific and only about 30 miles up the road from San Francisco, this sublime national seashore sees about 2.5 million annual visitors.

Fortunately, it’s rarely a problem shaking all this company. Or (speaking of shaking) forgetting that this tranquil setting is a tectonic hot zone in disguise, straddling the Pacific and North American plates on the world’s most famous fault line — the San Andreas.

You can acknowledge all of that on the short Earthquake Trail. Then head up the Bear Valley Trail (mind the horses and bikes) and promptly disappear along any number of quiet tributaries in the park’s 140-mile trail system to enjoy some of the sweetest stretches of NoCal coast. All furnished in groves of Douglas fir and Bishop pine, wildflowered meadows, and empty beaches that folks like Sir Francis Drake admired more than four centuries ago.

Until then, this land was the private sanctum of the Coast Miwok people, a federally re-recognized tribe now known as Graton Rancheria (after legislation in 2000) with more than 1,300 members. Honor their past at the Kule Loklo re-created village near the park visitor center, and honor their present during the park’s annual Big Time Festival in mid-July.

The Hearst Coast

Where: San Simeon, Central Coast

Don’t Miss: The best little elephant seal rookery on the coast (Piedras Blancas rookery, 4 miles north of Hearst Castle on state Route 1)

“We are tired of camping out in the open at the ranch in San Simeon,” William Randolph Hearst reportedly told San Francisco architect Julia Morgan in 1919, at the outset of their prolonged collaboration on Hearst Castle. “I would like to build a little something.”

Constructed over a span of nearly 30 years — and never totally finished — the media magnate’s humble hilltop home exemplifies the inadequacy of the word huge when describing certain properties: more than 80,000 square feet of living space divvied between the 38-bedroom Casa Grande and three Spanish-style guest houses, 127 acres of gardens, terraces, walkways, and a pair of fountain-festooned pools named after Neptune and Rome. The world’s largest private zoo has long since closed. And that’s just the brief overview.

Is there anything out here that could make Mr. Hearst’s little something — donated to the state in 1957 and now one of California’s top tourist Meccas — seem relatively small-ish? There is: the entire surrounding Hearst Ranch, which comprises more than 80,000 acres of magnificent coast and bucolic cattle lands.

Ranching has a 150-year history on the Hearst Estate, harking back to 1865, when William’s father, George, bought his first San Simeon parcel and started raising cattle, sheep, hogs, poultry, and other animals. Today, the property is one of the largest working cattle ranches on the California coast, its timeless Old Cali landscape forever preserved by one of the largest land conservation easements in the nation’s history.

“The Ranch has its own rich history, beginning long before the Castle was built,” notes Stephen T. Hearst in the foreword of Hearst Castle historian Victoria Kastner’s seminal Hearst Ranch: Family, Land, and Legacy (Harry N. Abrams, 2013), the first book to document the history of the actual ranch under the Hearst label.

All castles aside, the land is a living legacy that can put even the West’s most magnificent mansion in perspective.

Humboldt County

Where: 250ish miles north of San Francisco

Hansel and Gretel Moment: Visit Ferndale’s Gingerbread Mansion

If you’re gallery hopping in quaint coastal Mendocino, what’s another couple of scenic hours north in the car? You’re heading for Humboldt County, which is not the California of clogged freeways, but rather of towering redwoods and Victorian towns that sprang up to support mining and logging, which in turn fed a Gold Rush-burgeoning San Francisco. Ready yourself for that time-stood-still feeling of the late-1800s variety, when gingerbready architecture belied the rough-and-tumble nature of the industries fueling all the growth to the south.

The place to call your home base in these far-flung parts isn’t Eureka, the big city up this way — it’s little Ferndale, where you can make your home away from home at the delightful Gingerbread Mansion. Just south of Eureka and inland at the mouth of the Eel River, this charming great-for-a-getaway village of well-preserved “butterfat palaces” was built around the turn of the century by the area’s prosperous dairy farmers.

From Ferndale, Eureka’s an easy day trip. The port takes its name from the California motto — translation: “I’ve found it!” What you will find these days are loads of Victorians (the entire city is a state historic landmark) and industry that runs to fishing and cannabis as much as King Timber. But lumber has reigned for a long time here: When Eureka’s charter was granted in 1856, there were nine sawmills producing 2 million board feet of lumber every month.

The most famous of Eureka’s Victorian buildings — built of local redwood, naturally — is the grandiose 1886 Carson Mansion, home of lumber baron William Carson. Today you can only marvel at the over-the-top Queen Anne-style landmark from the outside (it’s now a private club) and join the many camera-toting admirers who have made the ornate confection one of the most photographed Victorians in the United States.

There are Victorian-housed antiques shops, restaurants, coffee hangs, art galleries, and bookstores to explore in Old Town Eureka, but one of the best stops in town is in a neoclassical bank building: the Clarke Historical Museum. Exhibits include Native American cultures, gold rush settlements, the lumber industry, ranching, farming, and fishing, but the terrific basket collection in the Native wing is reason enough to make a trip here. When you get outside again, walk among the big trees at Sequoia Park Garden or take a cruise on Humboldt Bay.

Get a bluff-top view of the bay and the Samoa Peninsula and a crash course in the region’s history at Fort Humboldt State Historic Park and Logging Museum just outside of downtown Eureka. Established in 1853 and staffed until 1870, it “assisted in conflict resolution” after settlers and gold seekers overran the county when gold was discovered in the Trinity River to the east and local tribes, having suffered too many attacks, finally retaliated. There are re-created surgeon’s quarters and a hospital with a re-created vintage herb and vegetable garden, and plenty of signage to paint a picture of the clash of cultures that happened here. Throw in some logging equipment (including vintage steam donkey engines), two operational logging locomotives, and an authentic redwood dugout canoe, and you’ve got a half-day’s worth of Western history like you never learned it in high school.

Catalina Island

Where: An hour ferry ride away from Los Angeles

Oh, give me a home: Zane Grey’s home is here, as well as a herd of bison descended from animals used more than 80 years ago in the film adaptation of Grey’s The Vanishing American

Ferrying 22 miles off the coast of Los Angeles with escorts of leaping dolphins and Jimmy Buffet lookalikes, one might naturally assume that Catalina — Southern California’s fabled leisure isle — couldn’t be further removed from the proverbial Wild West receding to the east in the rear view. But one soon learns differently.

Officially part of the remote Channel Islands chain, this easily accessed retreat got off the ground when chewing gum baron William Wrigley Jr. purchased the entire 76-square-mile island for a couple million bucks sight unseen in 1919, building a hilltop mansion, inviting his Chicago Cubs here for spring training, and shaping the island’s Mediterranean-style port town of Avalon into a casually refined offshore resort.

By the 1940s, Cecil B. DeMille and Winston Churchill were pulling into Avalon Bay to go fishing, and Glenn Miller and Duke Ellington were performing in Avalon’s landmark Casino Ballroom. Clark Gable, Charlie Chaplin, Errol Flynn, and Marilyn Monroe all had a good time here. So did John Wayne, who enjoyed escaping to Avalon with his family and fishing tackle between shoots.

But long before Hollywood’s A-list put Catalina on the map, legendary western writer Zane Grey made it his home.

Lured to Catalina Island by his second great passion — fishing — Grey first discovered Catalina on his honeymoon in 1906 (fishing for six straight days, as the story goes) before literary fame and fortune led the Altadena, California, resident and former Ohio dentist to build a second home here in 1926. He would spend summers in Catalina, writing in the morning and angling for record-breaking marlin and tuna in the afternoon.

One of the most prolific bestselling authors ever, Grey wrote about 90 books — more than half of them the sweeping western “sagebrush sagas” for which he is known. When he died in 1939, he’d penned so many unpublished manuscripts that they would continue to be released for years posthumously, spawning numerous film and TV adaptations that would spur the careers of emerging legends such as Gary Cooper, Randolph Scott, Wallace Beery, Ernest Borgnine, and many others.

His home — a ’20s-era Hopi-style compound — still stands, melded into a steep hillside overlooking Avalon. The longtime family residence eventually became the Zane Grey Pueblo Hotel; currently closed for renovations, it received guests for years. There, you could kick back in Dr. Grey’s old pad with a dog-eared copy of Purple Sage. Save for the faint toot of an Avalon ferry horn far below and some palm fronds swaying outside the window, coastal California would fade into the background. And you could lose yourself, not just somewhere west — but West.

Sonora

Where: Central Sierra Nevada Foothills

Featuring: The best timeless portrayal of Mayberry in Sierra country, with two classic Western historic state parks nearby

“Sonora is one large house of entertainment for bonâ-fide travellers,” penned roving English author Frank Marryat in 1851, recounting a visit to the so-called Queen of the Southern Mines during its California Gold Rush heyday. “No church bells here usher in the Sabbath,” he added. “[E]very man carried arms, generally a Colt’s revolver, buckled behind, with no attempt at concealment.”

Today’s Sonora is a mite milder. Not that traveling to this time-warpish charmer nestled in the Sierra foothills doesn’t offer plenty of here-and-now value. A lovely inn here. A popular bistro there. A tough-to-resist candy store across the road. Meandering among the town’s historic buildings of Washington Street leads past all of that and more.

Sonora’s next-door neighbors include Columbia State Historic Park, where the preserved Gold Rush-era business district is now furnished with bygone-era-style shops and proprietors in period costume. You can still pan for gold, ride a century-old stagecoach, or simply disappear into the park’s peaceful hillside trails.

Three miles south of Sonora, in equally fabled Jamestown, Railtown 1897 State Historic Park is nirvana for old-train buffs and features a still-chugging steam locomotive maintenance depot where visitors can board old iron horses for a ride through the Sierra foothills. The Virginian, High Noon, and hundreds of other westerns have all logged screen time at this hallowed rail site.

Empire Mine State Historic Park

Where: Grass Valley, Nevada County

Be Mine: Take your vows at one of California’s most popular and unusual wedding venues — the picturesque stone Empire Cottage and gardens

One of the oldest, largest, deepest, longest, and richest gold mines in California, Empire Mine produced 5.8 million ounces between 1850 and 1956 — extracted 8,500 feet down from 367 miles of shaft. An introductory video in the visitors center schools you on the 1849 Gold Rush and the technology and mechanics of 100 years of gold mining.

In the tours, you get another piece of the reality: the disparity between the lives of the mine workers and the wealthy owners. You can visit the operational blacksmith and machine shops and tour the mine yard to get the labor side. Tour the gardens, grounds, and “cottage” — the palatial residence designed by architect Willis Polk where the mine owners (the prestigious Bourn family) summered and entertained lavishly — to see how the 1 percent lived.

Besides the historical area, there’s a gold mine of nearly 850 acres for hikers, cyclists, runners, and horseback riders (bring your own mount) to explore.

Truckee/Tahoe

Where: Sierra Nevada Mountains

Cautionary Tale: Don’t let the Donner Party deter you from outdoor pursuits amid spectacular scenery

You can’t escape a couple of things in this nearly-Nevada part of North Tahoe: the incredible High Sierra scenery and the name Donner. The glories of the mountain West and the tragic emigrant story make for poignant juxtaposition — and profound experiences.

On the one hand, there are skiing (downhill, cross-country, water), hiking, camping, snowmobiling, fishing, boating, horseback riding, and mountain biking in a landscape that in any season calls to mind an ecstatic John Muir, who declared Lake Tahoe “Queen of the Lakes.” On the other hand, there are Donner Memorial State Park, where a new visitor center uses interactive displays to commemorate the local Washoe Tribe; the Chinese laborers who, among other things in the Old West, helped build the Transcontinental Railroad; and the ill-fated Donner Party.

One of the earliest pioneer wagon trains and probably the most memorable for its grim outcome, the Donner Party was forced to camp at the east end of Donner Lake in the winter of 1846 – 47, after taking the Hasting Cutoff, the supposed shortcut that ultimately caused the travelers to get stuck in the mountains for months. Enduring terrible suffering (perhaps resorting to eating those who had died of starvation and sickness), they ultimately lost almost half of their 91-person party.

It’s fitting to meditate on the almost incomprehensible difficulties those early settlers faced trying to find a brighter future in the Golden State. Fitting, too, for us lucky heirs to the promise they sought, that we should enjoy that golden good life: skiing, hiking, boating, or riding around beautiful and uncrowded Donner Lake; checking out the galleries, shops, and stiff paloma cocktails at Casa Baeza in charming historic downtown Truckee; then retiring in almost embarrassing comfort to a room at the swanky Ritz-Carlton, Lake Tahoe.

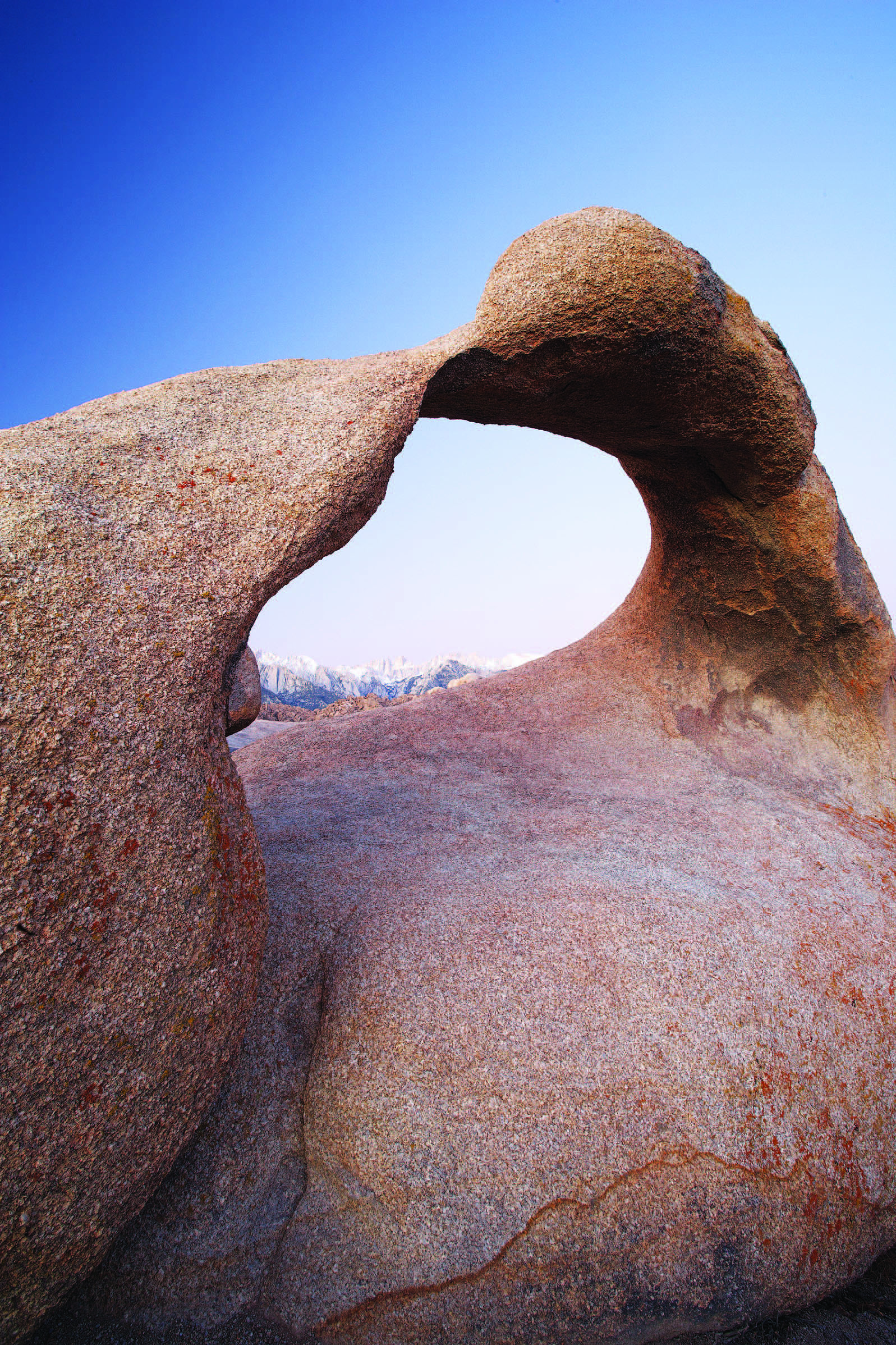

Lone Pine

Where: Owens Valley, near the Alabama Hills

Rare Sighting: A 16-mm-format screening of the first film shot at Lone Pine, The Round Up starring Fatty Arbuckle, at this year’s Lone Pine Film Festival, October 9 – 11

If places like the Alabama Hills and Mobius Arch off Movie Road look familiar, there’s good reason: More than 400 films have been shot in and around Lone Pine since the first 1920s silent western, The Round Up. Honoring the iconic location and paying tribute to its role in western moviemaking, Roy Rogers himself dedicated a historical marker in 1990.

You can find it at the corner of Whitney Portal and Movie roads, near the entrance to the Alabama Hills Recreation Area: “Since 1920, hundreds of movies and TV episodes, including Gunga Din, How the West Was Won, Khyber Rifles, Bengal Lancers, and High Sierra, along with The Lone Ranger and Bonanza, with such stars as Tom Mix, Hopalong Cassidy, Roy Rogers, Gary Cooper, Gene Autry, Glenn Ford, Humphrey Bogart, and John Wayne, have been filmed in these rugged Alabama Hills with their majestic Sierra Nevada background. Plaque dedicated by Roy Rogers, whose first starring feature was filmed here in 1938.” That feature, Under Western Stars, shares billing with The Gunfighter (1950), Bad Day at Black Rock (1955), Joe Kidd (1972), Maverick (1994), and The Lone Ranger (2013) as just some of the many films in which Lone Pine plays the part of Great Western Backdrop.

The Lone Pine Film Festival always takes place the second weekend in October. The 2015 theme: Westerns — The Early Years, paying special tribute to Tom Mix, whose 1937 Cord will be on exhibit at the artifact-filled Beverly and Jim Rogers Museum of Lone Pine Film History.

Paramount Ranch

Where: Santa Monica Mountains, Agoura Hills

Walk This Way: Stroll through “Western Town” followed by a short hike up the Coyote Canyon Trail

Tucked away on the far side of the Santa Monica Mountains on the sleepy edge of Agoura Hills, Paramount Ranch was purchased by its namesake studio in 1927 — the perfect 2,700-acre patch of mountains, canyons, and creeks to launch the busiest off-site western film set in the biz. Changing hands several times over the decades (and now managed by the National Park Service), the property has hosted the stars and crews of hundreds of movies and TV shows. Among them: vintage classics such as Gunsmoke, Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, The Cisco Kid, and more recent productions like Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman.

A daily 3-mile-loop trail ride with Malibu Riders takes you from Malibu right through the ranch. Seeing it from the saddle will put you in mind of the California of yore — Gary Cooper, coyotes, bobcats, and all.

Salinas

Where: Half-hour east of Monterey

Best Alliteration: Rodeo, writers, and race cars

Rancho Mission Viejo Rodeo in San Juan Capistrano gets props for being the richest two-day rodeo in the nation, but six hours northwest, Rodeo California Salinas is the state’s largest. Rodeo “Big Week” — this year, from July 16 to 19 — features three rough stock events (bareback riding, saddle bronc riding, and bull riding) and three timed events (tie-down roping, steer wrestling, and team roping), all PRCA-sanctioned.

Go with a little history under your trophy-buckle belt. Although Salinas is known as the Salad Bowl of the World for its agriculture and as a racing Mecca for its Mazda Raceway Laguna Seca, rodeo has been a big deal since 1911, when a local group of cattlemen known as the Salinas Coyotes held what they initially billed “a Wild West Show” on racetrack grounds. Over the years the event grew (and grew) and has hosted a passel of Hollywood VIPs, including Will Rogers and Gene Autry.

But while Salinas is all about rodeo in July, it’s Steinbeck country year-round. The Nobel Prize-winning author John Steinbeck was born here, and his ashes are interred here. The restored 1897 Queen Anne-style Victorian that was his birthplace and boyhood home offers limited public tours and a restaurant. If you really want to dig in to the author, head for the National Steinbeck Center, a premier collection of Steinbeckiana that includes Rocinante, the camper truck that carried Steinbeck cross-country for Travels With Charley: In Search of America.

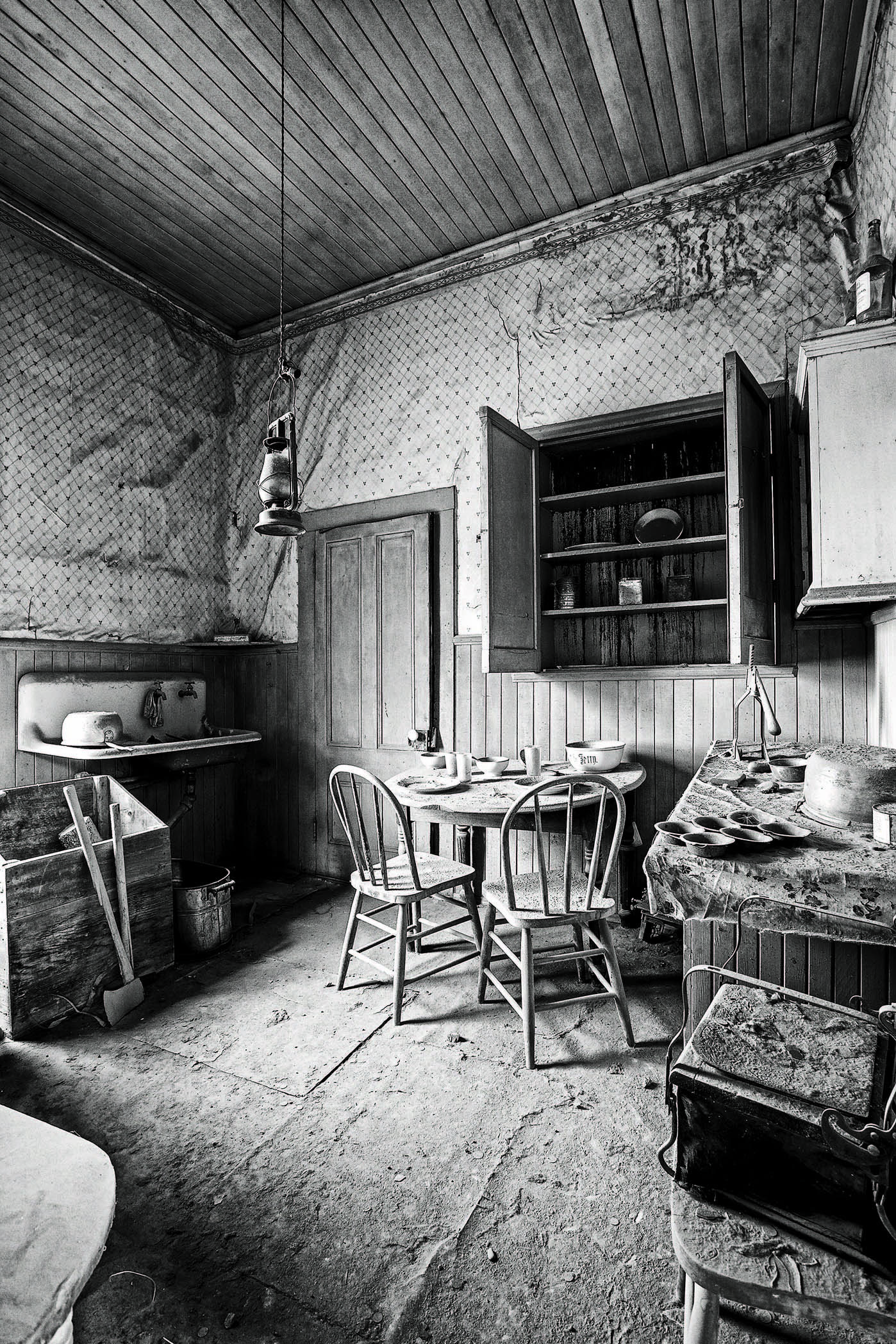

Bodie

Where: Eastern Sierra Nevada

Claim to Fame: Best real ghost town in the West

California’s foothills are dotted with historic gold-mining towns living out various forms of retirement or reinvention. The most authentic of them all, Bodie, will not be competing for your quesadilla money, souvenir dollars, or B&B patronage today. But, man, if you’d been here 140 years ago ...

The National Historic Site and state-run park (designated in 1962, when it was deemed “probably the finest example of a mining ghost town in the West”) was once booming with nearly 10,000 fortune seekers following a sizeable gold discovery in the mid-1870s after a serendipitous mine cave-in. Within a few years, new mines were everywhere. So were all the saloons, dance halls, brothels, and breweries that naturally accompany gold-fever hordes to a desolate spot perched at more than 8,000 feet on the back side of the Sierras in the middle of absolutely nowhere.

And then they were gone. The town’s last die-hard residents vanished more than 50 years ago.

Today, Bodie’s haunting grounds lined with empty buildings exist at the end of a 3-mile gravel road off a lonely highway about 20 miles from its closest existing town (Bridgeport) in a preserved state of “arrested decay.” No gift stores. No saltwater taffy shops. No inns or filling stations. Just wind, ghosts, and the sense that most manic human endeavors eventually come to this.

Santa Ynez Valley

Where: Just northwest of Santa Barbara

Put Down That Pinot: This former stagecoach stop serves up more than just wine

What most people know about the Santa Ynez Valley, they know from the wine-buddy film Sideways. But this breathtaking valley tucked between the Santa Ynez Mountains to the south and the San Rafael Mountains to the north offers a lot more than the promise of re-creating the adventures of Miles and Jack. Obviously, there are wineries — dozens of them. The tasting rooms of the 16 family-owned wineries of the Santa Ynez Valley Wine Country Association are within 6 miles of each other among the rolling hills and ancient oaks of gorgeous ranch land that stagecoaches once plied.

But before you appoint your designated driver or climb in your wine-tour limo, get your Old West fix at the Santa Ynez Valley Historical Museum and Carriage House in historic Santa Ynez. Exhibition spaces devoted to Native Americans (the Chumash were here first) and pioneers include historical clothing and other artifacts, but it’s the Parks-Janeway Carriage House, adjacent to the old Santa Ynez jail, that really evokes that bygone era. With more than three dozen carriages, it’s one of the finest authentic carriage collections of its kind in the country, and also features saddles, bridles, harnesses, and other tack by the likes of Visalia Stock Saddle Co. and The Bohlin Company.

As early as 1858, the stagecoach ran from Yuma, Arizona, to San Francisco, with stops at one time or another in or near the Santa Ynez Valley communities of Ballard, Buellton, and Los Olivos. The horse was as influential in the valley’s late 1880s stagecoach era as wine is today. Which is not to say that the horse has lost its mojo here — far from it. These days, the Santa Ynez Valley’s scenic ranches revolve largely around the sale of cattle and horses, and some of the horse ranches are nationally recognized for their Arabians and Thoroughbreds. There’s wonderful riding (for overnight guests) at the luxe Alisal Guest Ranch and Resort and scenic day rides at the historic (1896) Nojoqui Horse Ranch.

When at last you rejoin the Sideways tippling trail, it might be back in Los Olivos at the Los Olivos Cafe, where Miles denigrated merlot, or at the Fess Parker Winery (yes, as in Davy Crockett), which was a stand-in for “Frass Canyon Winery.” Or venture out of the valley to the edge of Vandenberg military base and the former Old West cow town of Casmalia, where some of the best barbecue and grilled artichokes in the West await at the Hitching Post I.

Julian

Where: Mountains of San Diego County

Highlights: Autumn foliage and awesome apple pie

Northern California’s surplus of quaint hillside towns full of Gold Rush history and mountain scenery defies choosing a single favorite. Not so in the state’s deep south, where the singular former mining community of Julian (just 60 miles, 4,235 vertical feet, and a world apart from San Diego) handily wins SoCal’s blue ribbon for revamped historic mountain town.

Originally inhabited by the Kumeyaay people, the California Historical Landmark nestled in the Cuyamaca Mountains experienced a short-lived gold boom in the 1870s, ballooning the population to 1,500 hopefuls before dwindling back down to almost nothing when most of the mines closed the following decade.

One upcoming sesquicentennial later, the happy lesson in Julian lives on: When life cleans out your gold stock, plant fruit orchards, serve up some Victorian B&Bs, and sprinkle in quaint stores and fudge shops along a fetching four-block Main Street. Oh, and make really, really good apple pie.

Greater Julian’s varied assets include a history museum stuffed with pioneer and Native artifacts in a converted blacksmith shop, the nearby California Wolf Center, a dramatic drive to the lofty observatory of Palomar Mountain, and four actual seasons in a corner of California that otherwise doesn’t really understand the term. The town’s lovely, lofty, folksy setting brings in droves of visitors on weekends and (psst) less traffic during the week.

If you take your SoCal mining towns with a slice of apple pie (for which the town and its surrounding apple orchards have become especially famous), then Julian is your real sweet spot. The “big three” pie joints here are Moms Pie House, Apple Alley Bakery, and the Julian Pie Company — all within a few blocks of each other.

Death Valley

Where: Mojave Desert

Best Reason to Get Out of Bed: Sunrise at Dante’s View

You could dig up episodes of Death Valley Days, the long-running radio and TV show presented by 20 Mule Team brand borax products and narrated by “The Old Ranger,” who would introduce “a new and exciting yarn — true, mind you — about the historic Death Valley country.” You could glean a lot from just listening to or watching them (including how a 26-year-old Clint Eastwood carried off his role in the episode “The Last Letter” and how Ronald Reagan handled his final work as an actor). Or you could go to the Mojave Desert and explore the otherworldly and strangely beautiful place yourself.

The off-putting name came from gold seekers crossing the arid expanse to get to the gold fields in California. Miners who stayed likely found work with Death Valley’s Harmony Borax Works, which from 1883 to 1888 famously used 20-mule team wagons to transport partially refined borax. It was really hard work, in a really hot place: The highest reliably recorded temperature of 134 degrees here beats all known hellish heat in the world.

The Timbisha Shoshone have been here since time immemorial. The “Old Ones” named the place Timbisha after the valley rock they used to make red ochre rouge. About 30 descendents still live in the Indian community village at Furnace Creek.

You, on the other hand, may not want to live here, but it is certainly worth a visit for the amazing natural surroundings. Just two words of advice: water bottle.

Autry National Center of the American West

Where: Los Angeles

Claim to Fame: The Singing Cowboy’s swan song — a multifaceted celebration of the American West

How exactly was the West won? Or at least vividly captured on film, TV, radio, stage and in myriad other ways? Tracing any facet of the career of legendary “Singing Cowboy” Gene Autry (the only person awarded all five achievement-category stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame) can provide several clues. None more significantly than the icon’s prize legacy: The Autry.

The main Griffith Park facility houses one of the most comprehensive collections of Western artifacts, artwork, historical docs, archival film footage, and firearms anywhere. There are additional collections at the nearby, but oft-missed, Southwest Museum of the American Indian.

Want to add to your own collection? The museum’s annual Masters of the American West, held at the beginning of the year, is one of the country’s premier Western art exhibitions and sales.

From the July 2015 issue.