Among dozens of historic icons who dedicated their lives to what’s been called “America’s Best Idea,” here we salute four standouts in the American West.

John Muir (1838 – 1914)

No single figure symbolizes America’s devotion to its treasure-trove of superlative landscapes more than this Scottish immigrant turned Wisconsin farm boy turned world-renowned naturalist, conservationist, explorer, author, and Sierra Club cofounder and first president. Gravitating to California’s Yosemite Valley as a young man (where he walked from San Francisco), John Muir’s dedication to the whole park idea and the wildlands of the Sierra Nevada in particular culminated in the creation of Yosemite and Sequoia national parks in 1890 (he was also a prime mover in the creation of Mount Rainier, Petrified Forest, and Grand Canyon national parks) and a famous three-night camping trip in Yosemite with President Theodore Roosevelt in 1903 that led to some of the most important conservation legislation in the country’s history, including the establishment of the U.S. Forest Service.

For more than four decades, Muir would serve as a figurehead for the national park ideal and man’s essential connection to nature, writing reams of ecstatic prose on the subject, eloquently imparting his message throughout the West, and living by example—to the point of climbing a 100-foot spruce tree in a raging Sierra wind storm just to feel closer to it all. “Everybody needs beauty as well as bread,” Muir would note. “Places to play in and pray in, where nature may heal and give strength to body and soul alike. This natural beauty hunger is made manifest ... in our magnificent National Parks— Nature’s sublime wonderlands, the admiration and joy of the world.”

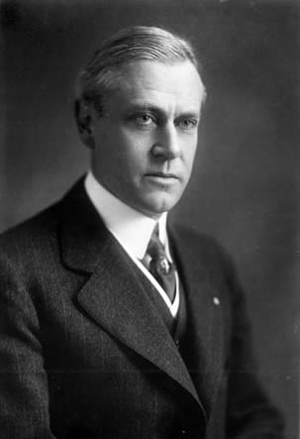

Stephen T. Mather (1867 – 1930)

“This nation is richer in natural scenery of the first order than any other nation; but it does not know it,” declares an inaugural manifesto of America’s National Park Service, stamped with the name Stephen T. Mather on the cover page. “It possesses an empire of grandeur and beauty which it scarcely has heard of. ... The Nation must awake, and it now becomes our happy duty to waken it to so pleasing and profitable a reality.”

A San Francisco-born borax mining executive, self-made millionaire, and ardent outdoorsman buoyed by an intense mission to safeguard America’s national parks from rampant mismanagement and deterioration, Mather spent much of his life and plenty of his own money to put these words into federally regulated effect. He did so by spearheading the creation of a Washington-based bureau to preside over national parks and monuments — which had not yet been created for the few already in existence.

On August 25, 1916, after years of nationwide campaigning and lobbying, Mather’s hard-fought dream — a National Park Service — was officially authorized by President Woodrow Wilson. Appointed its first director, a position he would hold for the next 12 years, Mather would help mold the NPS into one of the most prestigious arms of the federal government. “He laid the foundation of the National Park Service, defining and establishing the policies under which its areas shall be developed and conserved unimpaired for future generations,” summarizes a series of bronze plaques honoring his memory in many parks. “There will never come an end to the good that he has done.”

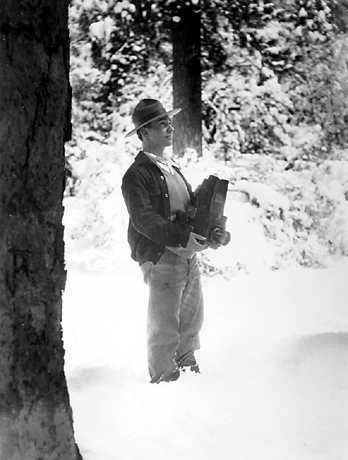

George Melendez Wright (1904 – 36)

Today, it may be hard to imagine that the concept of “wildlife conservation” was once a backwoods idea requiring the tireless efforts of a few visionaries to bring it into public view. But it wasn’t until 1929, when a young man named George Melendez Wright initiated a seminal wildlife survey program, that the issue really got its due at the National Park Service.

As an assistant naturalist at Yosemite, Wright was struck by disturbing trends among park fauna: among them, an oversupply of tame mule deer and a dearth of natural predators, the impacts of poaching, and increasing black bear dependence on human garbage as a food source. Launching his own self-funded four-year scientific survey of animal and plant conditions in national parks, Wright made observations and recommendations that would alter ingrained park practices (like killing predators and feeding bears at dumps) and lead to the formative work Fauna of the National Parks of the United States — the first of an ongoing series used to monitor and protect park wildlife.

Named the first chief of the NPS’s new Wildlife Division at the age of 29, Wright grasped the need to view national parks not just as scenic wonders but also as complex ecological systems requiring careful scientific monitoring and attention. He would pioneer modern management and conservation practices of rare, endangered, and indigenous species in America’s parks until his untimely death in 1936 in an automobile accident. The George Wright Society, a nonprofit association, honors his legacy.

Theodore Roosevelt (1858 – 1919)

No story about the evolution of our national park system could be complete without a serious nod to Theodore Roosevelt, who after becoming president in 1901 facilitated the 1906 American Antiquities Act, the first law establishing archeological sites on public lands as important public resources. He created the United States Forest Service and established 150 national forests, 51 federal bird reserves, four national game preserves, five national parks, and 18 national monuments. All told, he protected approximately 230 million acres of public land while president. His dedication to conservation is one aspect of the greatness that earned him a place on Mount Rushmore. It’s also what merited his own national park in the Badlands of North Dakota, where he regained his strength after a barrage of personal tragedy in the East and was first inspired to a life of important protection efforts that would cause him to be known as the “conservation president.”