Summers spent on the Chitimacha Reservation in Louisiana led the artist to join two worlds — blending contemporary photography with traditional basket weaving.

In re-creating the traditional baskets of her Chitimacha ancestors, visual and mixed-media artist Sarah Sense doesn’t use river cane harvested from the banks of the Bayou Teche in Louisiana, where the tribe cuts, splits, peels, dries, and dyes it red, black, and yellow before weaving and bending it into time-honored patterns that have been passed down for generations. Nor does she shape her woven creations into vessels meant to store or carry the corn, squash, and other crops her skilled horticulturist ancestors cultivated in the Mississippi River Delta for the thousands of years the tribe has inhabited the region.

In fact, Sense doesn’t weave baskets at all — her “basketry” is actually woven photography. Sliced like river cane, strips of images are woven into tribal patterns, which in turn become finished works of art that hang everywhere from the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., to the Tweed Museum of Art in Duluth, Minnesota.

It was life on the Chitimacha Reservation and journeys well beyond it that led Sense to her distinctive art. Raised in Sacramento, California, the daughter of a half-Chitimacha, half-Choctaw mother and a father of European descent, Sense attended California State University, Chico, where she received her B.F.A., focusing on painting and abstract expressionism. But her summer vacations were spent on the Chitimacha Reservation in Charenton, Louisiana. There, she worked among the community — a condition for a college scholarship she’d received from the tribe — and fell in love with the art of basket weaving.

But Sense encountered difficulties learning the disappearing craft. So it was serendipitous when the tribe’s cultural department asked the then-18-year-old to visit the Southwest Museum of the American Indian in Los Angeles to investigate rumors that a cache of rare Chitimacha baskets was stored among its artifacts. At the museum, Sense delved into the archives and discovered that it did indeed own about 100 baskets, some with woven patterns that the cultural department had never known existed.

The elders were shocked — and the young artist was smitten. “The baskets were very precious,” she says. “They were traditional. They represented the present, and they represented the future. I loved the idea that I felt like I connected to them in a spiritual way, in a physical way.”

After her exciting discovery, Sense continued to live on the reservation during the summer months, bonding with newfound family members and deepening her cultural ties to the Chitimacha Nation. But while her desire to re-create the baskets of her ancestors grew, she lacked the time to fulfill the traditional requirements — including harvesting and preparing the cane — to learn the closely guarded sacred practice.

Sense became her own weaving instructor after landing at Parsons The New School for Design in New York City for her M.F.A. in studio art. There, she spent hours in the library, unearthing books on the Chitimacha Tribe, poring over basket patterns, and presenting her findings to her professors and classmates. “I wanted so much to weave, and I wanted other people to see the importance of weaving,” she says.

During the summer of 2004, Sense revisited the Chitimacha Reservation, this time viewing it through the fresh eyes of an artist and scholar. She took photographs of the community and purchased a basket from one of the tribe’s weavers. Most important, she scheduled a meeting with Alton D. LeBlanc Jr., the then-chairman of the Chitimacha Tribe of Louisiana, to seek his permission to weave tribal baskets using nontraditional materials.

“I asked for his blessing,” she says. “I knew that it was time, [but] I had no idea what it was that I was going to weave.” LeBlanc gave her his blessing, reassuring her that “being Chitimacha is part of who I am; it is my community.”

Back in New York, Sense studied the basket she’d bought and examined its construction. She then took a photograph she’d shot of a Native tanning salon and Photoshopped it into yellow, red, black, and white hues. Next, she cut the picture into small strips and wove them together in a Chitimacha basket pattern. “I didn’t really know what I was doing. I had never seen anything like this before,” she admits, but her teachers saw the final product’s promise and encouraged her to produce similar works.

“Things progressed, and I did a few more landscapes,” Sense says. “I made them different sizes. I was making baskets, little things.” Before she knew it, she was no longer just a painter. She was also a weaver and a photographer.

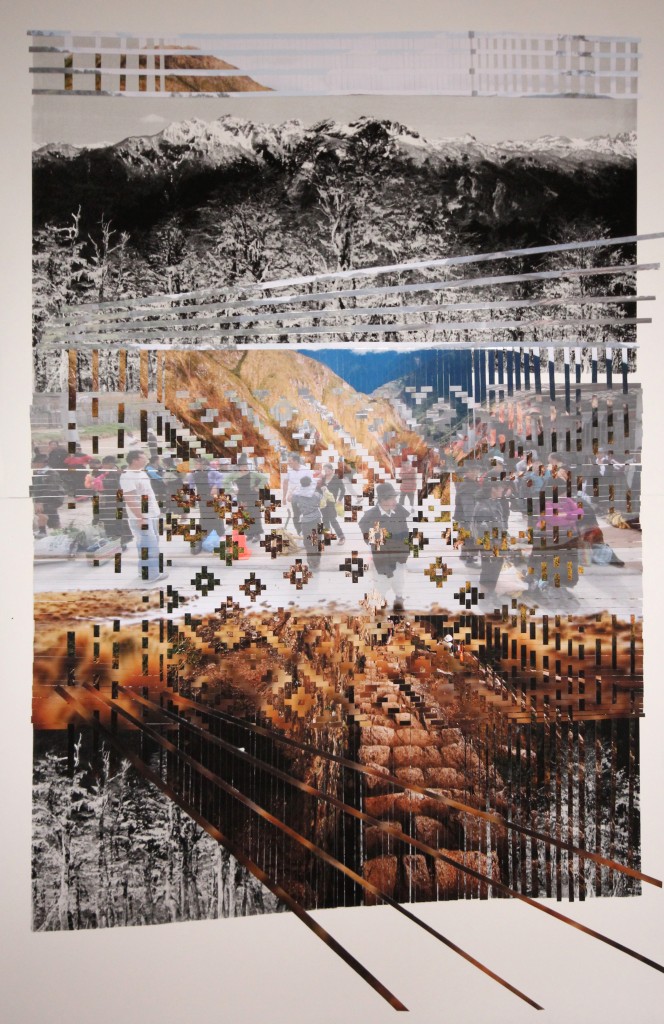

Sense’s art begins with photos of far-flung places she has taken with her digital camera. She then prints the images onto paper, sometimes after digitally combining multiple images or manipulating the colors. Slicing the paper into thin strips, she manually plies the shredded shots back together into the intricate designs of her tribe, superimposing them over photo silk-screen prints.

Sense sometimes also threads handmade paper, ripped-up journal entries, family portraits, and personal documents into her elaborate compositions. The result? A deeply personal collage-cum-photographic-landscape of sorts — with a basket texture where each of the individual “fibers” pays homage to the disparate cultures, histories, and heritages that influence Sense’s artistic identity.

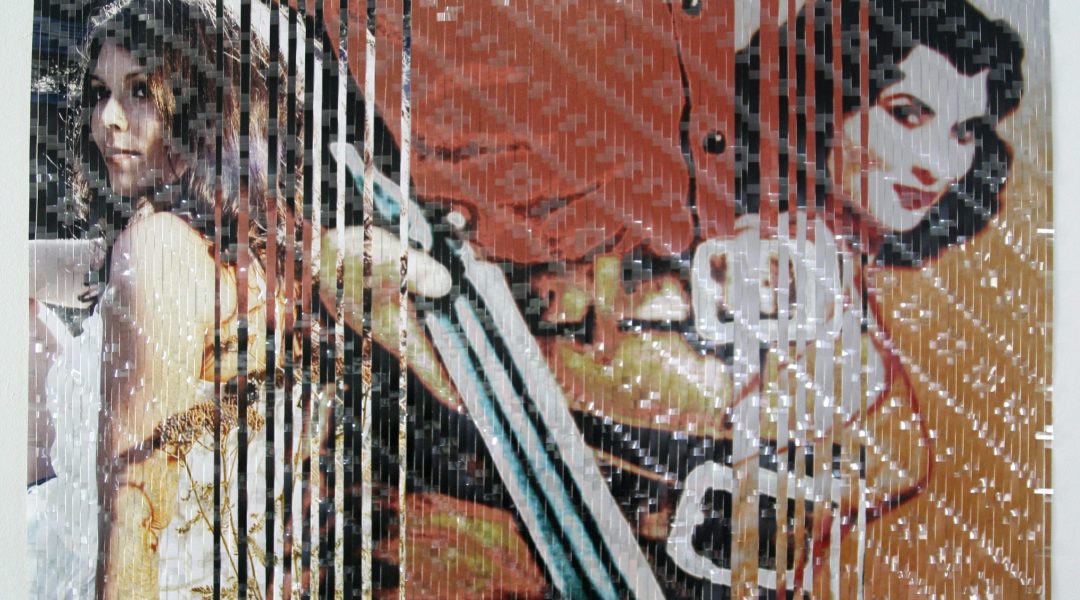

In the years since weaving her first 8-by-8-inch photo “basket,” her work has evolved into a prolific career filled with exhibitions, travel, and various themed projects. She has deconstructed cultural and gender stereotypes in western movies through her Hollywood series, in which she wove juxtaposed images of Indian princesses, cowgirls, and American Indians. Most recently, she took photographs of landscapes across North and South America, Southeast Asia, and the Caribbean and wove them together with disparate materials — handmade bamboo paper from Thailand, for example, which resembles the cane of the Bayou Teche — in an attempt to trace native art forms that link indigenous tribes across the world.

In 2012, Sense published Weaving the Americas: A Search for Native Art in the Western Hemisphere, a color catalog that chronicles her art, journal entries, and interviews with artists from her travels through a dozen countries ranging from Canada to Chile. The cross-continental journey landed Sense her first traveling solo exhibition, the aptly titled Weaving the Americas, which premiered at Museo de Arte Contempráneo in Valdivia, Chile. Subsequent works inspired by trips to the Caribbean and Southeast Asia were showcased in Weaving Water, a 2013 exhibition at the Rainmaker Gallery in Bristol, England.

While diverse in subject matter, all of Sense’s works share the same goal: to entwine the world’s stories with her own. “I see things coming from north, south, east, and west and colliding,” she says, “and then quite literally being woven together.”

Sarah Sense is represented by King Galleries in Scottsdale, Arizona, and Sorrel Sky Gallery in Santa Fe.

From the February/March 2015 issue.