With his Oki Language Project, Blackfoot actor Eugene Brave Rock is helping preserve Indigenous cultures.

Most moviegoers know Eugene Brave Rock for his standout role as a demigod in 2017’s Wonder Woman, where he starred alongside Gal Gadot, Chris Pine, and Robin Wright. In the blockbuster film, the First Nations actor speaks Blackfoot in an early instance of authentic Indigenous representation within contemporary pop culture. Brave Rock knew that was a rarity at the time, but he didn’t fully comprehend the meaningful impact it would have on audiences — especially his own people.

“My love of language and culture was instilled in me by my grandmother, so having the opportunity to share our language on Wonder Woman was huge,” says the 46-year-old actor, who grew up on the Kainai Nation reserve in Alberta, Canada. “I didn’t realize just how powerful it was until I went home and all these people were telling me that they cried when they heard our language on the big screen.”

Although that happened by chance (more on that later), it brought together Brave Rock’s passions for acting and language while also setting him on a path to quietly found the Oki Language Project back in 2020. The nonprofit organization takes its name from the Blackfoot word for “hello,” which speaks to the initiative’s seemingly straightforward mission: to document and celebrate greetings and other common phrases in as many Indigenous languages as possible. While that ambition may seem simple on the face of it, it has taken the actor on a great journey — both literally and figuratively — to learn from elders in tribal communities across North America.

“Language is so powerful because it helps us understand who we are and where we come from,” explains Brave Rock, whose rugged exterior belies his sensitive, soft-spoken nature. “Most people don’t know whose land they stand on. My goal is for all of us to be able to acknowledge the people whose land we stand on, whether you’re in Santa Fe or Los Angeles, and to recognize their culture and way of life by speaking their language.”

Scroll down to find out how to donate to and support the Oki Language Project and get an original Joseph Kayne illustrated tintype.

Speaking From Experience

Long before launching the Oki Language Project, Brave Rock was learning to better speak his own language with the help of Blackfoot elder Sheldon First Rider, who has dedicated much of his life to this work. They even joined forces on the Blackfoot Language Revival, which strives to marry tradition and technology with apps and other educational tools.

In mentoring Brave Rock, First Rider impressed upon him the role that they play in this work. “It’s the elders who deserve all the credit,” says First Rider. “I’m very proud of Gene for all the work he does, but we both understand we’re just instruments in preserving our way of life and showing that we’re still here.”

Brave Rock carried that guidance with him as he kicked off his Oki initiative, naturally starting with his own language. “We sat with 10 elders from the four Blackfoot tribes for five days listening to their stories and recording common words and sayings,” he explains. “It’s so powerful to be able to sit with our elders and learn from them. I’m not there to extract or steal anything; that has happened too many times to our elders. Instead, this is about them telling their stories. I always come with protocol, offering sweetgrass, sage, tobacco, food, water, blankets, and other gifts as a sign of honor and respect.”

When he’s not busy on set acting in shows such as AMC’s Native-themed noir Dark Winds or Netflix’s spaghetti Western That Dirty Black Bag, Brave Rock is on the road visiting Indigenous communities. Those efforts began in earnest last year, and within a matter of nine months, he had put an estimated 40,000 miles on his 2018 Chevy Silverado. He uses his own truck to haul an Airstream trailer (provided by the project’s solo partner) where his listening sessions take place.

Voices That Carry

The project is still very much a labor of love, though Brave Rock hopes more sponsors sign on to help fund the worthy mission. “At this point, it’s just a one-Indian show,” he says with a laugh. Jokes aside, there’s plenty of voiced support for the Oki Language Project from the Indigenous luminaries who make up the organization’s council, including Cherokee actor Wes Studi, Hunkpapa Lakota actor Zahn McClarnon, and Shoshone/Hopi/Mexican rapper Taboo Nawasha of the Black Eyed Peas.

Studi immediately signed on when Brave Rock asked for his backing. “Our language is reflective of our personhood; it’s how we honor our ancestors and carry on the ways of life that created who we are today,” says the septuagenarian actor, who exclusively spoke his Cherokee language until he was 5 years old and began attending public school, then boarding school. “It’s also important in terms of sovereignty, which most Native tribes here in the United States have been working toward for decades. It’s a matter of preserving who we are and our ideas about the world around us.”

Among the elders Brave Rock has sat with is Rose Tsosie-Gomez, a Diné artist who lives on the Navajo Nation. Like Studi, she spoke only her people’s language until she went to boarding school at age 6. She was there for a decade, followed by public school. She points to boarding schools and policies like the Indian Relocation Act — which aimed to assimilate Indigenous communities into American society by moving them off Indian reservations and into urban areas — as major causes of the erosion of Native language knowledge.

“The way of life was very different 60 years ago; we all spoke Navajo at home back then,” says Tsosie-Gomez. “Learning English was a very hard task, and I believe the younger generations started speaking more in English so that their children didn’t have to go through that experience. But now we do have schools where they teach only in Navajo, and it’s so nice to hear the kids speaking and singing in our language. It’s vital for our identity and our heritage.”

First Rider doesn’t mince words about the harm done to Indigenous communities through oppressive colonial-era practices, like forcing tribal nations to sign unjust treaties. “Who would sign to have their lands taken away from them?” he says. “Who would sign to have their children taken away from them and put into those jails that they call residential schools? Who would sign to have their language, their culture, and their history taken away from them? When colonization came, they outlawed our languages and a lot of it was lost. But it is only through language that we stay connected to creation.”

For The Record

To date, Brave Rock has compiled more than 100 hours of video and audio recordings from his time with culture bearers, some of whom have passed away since their time together. That highlights the crucial nature of this work, given that much Indigenous knowledge stands to be lost if it’s not passed down orally by these elders. This information gathering will be an ongoing endeavor, and Brave Rock intends to eventually develop a language library with assets that can be shared far and wide across social media and beyond. But using his platform to promote Indigenous cultures in this way is just the start.

“I really want to produce movies and develop video games featuring our languages and telling our stories through the lens of who we are,” he says. “Being that kid from the reservation who was raised by my grandmother, I feel so blessed to be able to carry on one of our oldest traditions: storytelling. Acting is a contemporary way of keeping our stories alive.”

Which brings us back to the backstory behind the Blackfoot language making an unplanned appearance in Wonder Woman. As Brave Rock tells it, when he tried out for the role, he didn’t know he was reading for the blockbuster film and came away from the audition feeling like he’d totally flopped.

“It was my first time in Los Angeles, and even though I had been studying my lines for two days straight, when it came down to the audition, I froze and couldn’t do it,” he remembers. “The casting director had me read my lines off the paper. I had taken a big swing, and it was really hard to accept that I had bombed it.”

He must not have made such a terrible first impression, because two months later, Brave Rock was on a plane to London to meet with the movie’s director, Patty Jenkins. Over breakfast, she asked if he was comfortable with the moniker “the Chief,” given that it’s written that way in the DC comic books, then inquired if he spoke his Native language. Upon learning that he indeed does, Jenkins made an impromptu decision to let Brave Rock come up with his character’s name and introduce himself in his language — a stark contrast to most of his acting and stunt-performing experiences up until that point.

“At the beginning of my career, I didn’t have any power to advocate for this kind of representation,” he says. “I remember once playing a warrior going into battle, and we were portrayed as dirty — like we didn’t bathe for a month. I explained to the producer that if we were going into battle, we’d actually be dressed in our finest clothes and have our hair braided a little tighter and neater. The answer back then was, ‘This is my story, not ours. Do you want to work or not?’ So to be a part of this movement today introducing people to our cultures and our languages is really amazing.”

To accomplish the task Jenkins asked of him, Brave Rock did his due diligence researching, laid down some tobacco, and prayed. Then his character’s name and identity came to him: Napi, a trickster demigod who features prominently in the Blackfoot creation story.

“I thought, if Wonder Woman’s father could be the Greek god Zeus, why can’t my character come from a Blackfoot god?” he recalls. “In our [Blackfoot] stories, we learn lessons from Napi by watching him do what he isn’t supposed to do; he is both Cain and Abel in one. That gave us an entire backstory, and Patty loved it. I’m so thankful for her giving me that power, because that was never in the script.”

The universe seems to have put that opportunity in front of Brave Rock in order to remind him, his community, and his fans of his superpowers: promoting and protecting Indigenous languages.

“As a future ancestor, I know my power is in my voice,” he explains. “This is about respecting our elders but also bridging that gap to our youth. It’s about celebrating those differences that make us unique as Indigenous people.” And it’s about recognizing the power of something as seemingly simple as a kind hello.

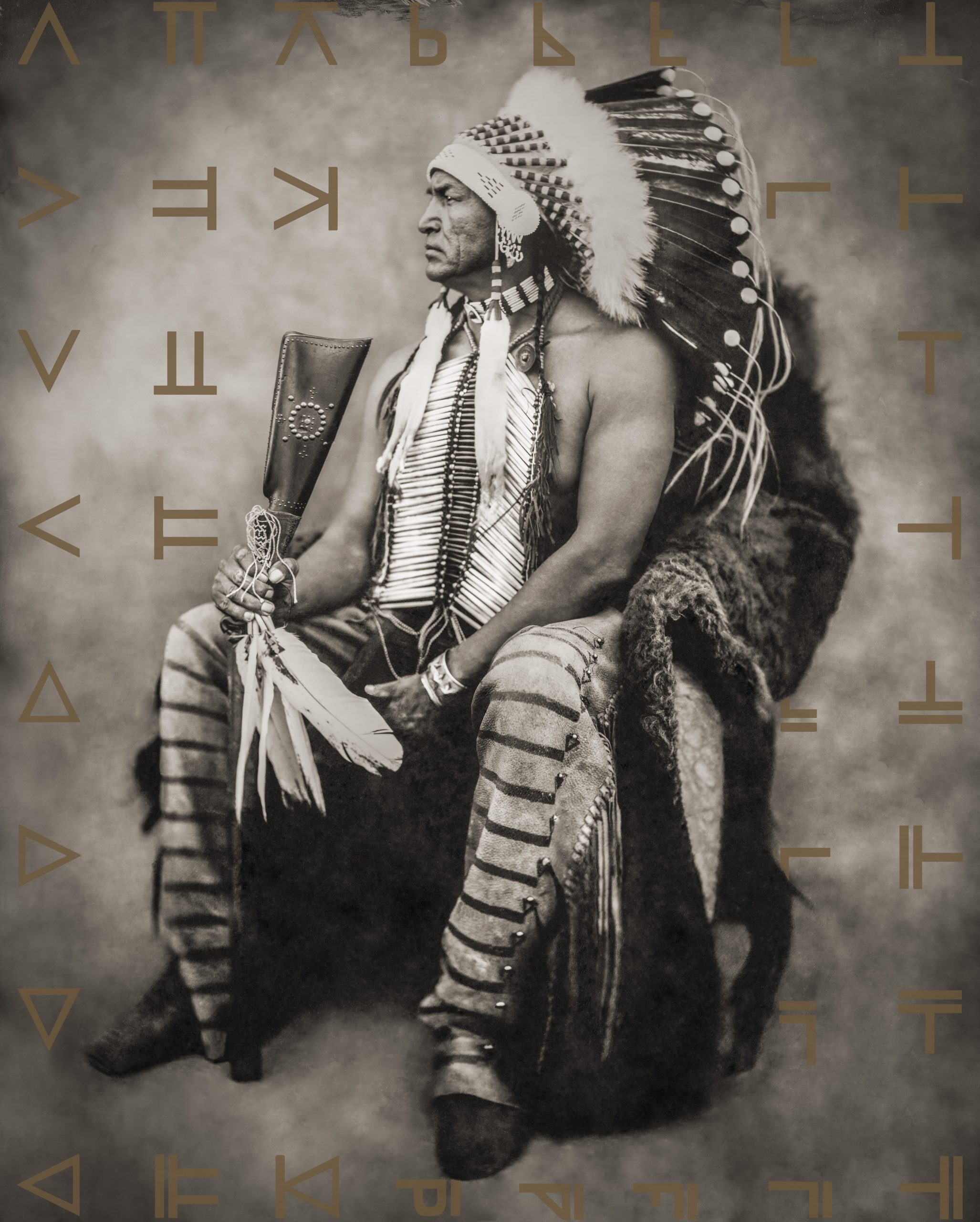

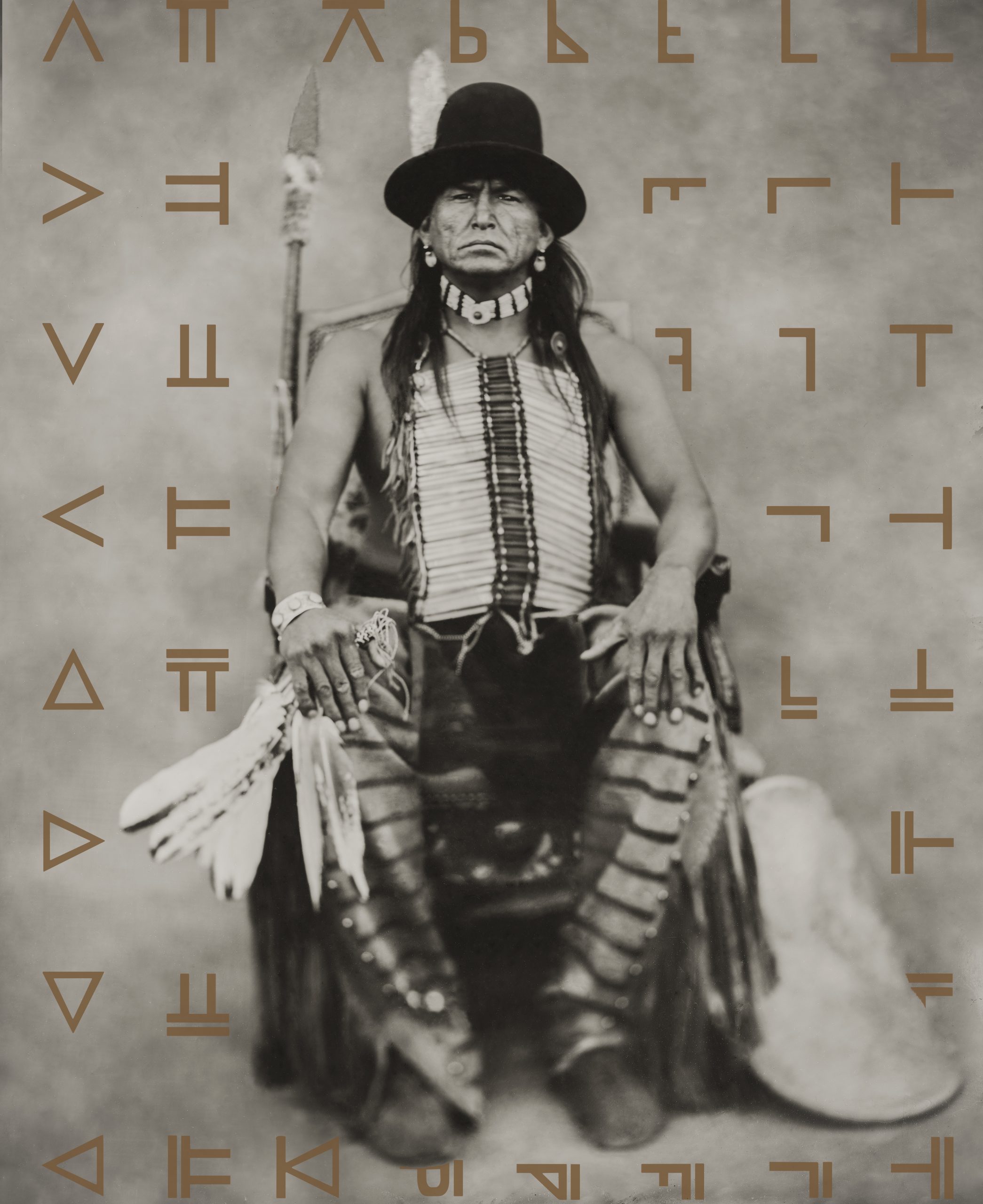

Support the Oki Language Project with the purchase of a limited-edition signed tintype digital print.

In collaboration with Cowboys & Indians and photographer Joseph Kayne, who specializes in the bygone art of wet plate collodion tintype photography, Gene Brave Rock is pleased to present an exclusive opportunity to support the Oki Language Project. For a limited time, you can get a signed tintype print, with proceeds supporting this worthy cause.

>>> Make a donation and find out how to receive a signed print here.