How a western film looks can be as important as who is in it.

From the silent films of William S. Hart and Tom Mix to today’s Wild West sci-fi adventures, Hollywood has long had a love affair with westerns. No film genre is more typically American. It’s also one of the more unlikely places to see good film design.

Known in the industry as production design and art direction, film design is the visual art of the narrative. Because production designers and a team of set decorators, artisans, and craftsmen create the overall look of a film, the craft is considered one of the most important aspects of filmmaking. Painstaking historical research is required for authenticity, which translates into believability. Storytelling and action must be coupled with a picturesque setting; in westerns, this can mean anything from the iconic scenery of Monument Valley to the frontier towns of Hollywood backlots.

With its dusty terrain and jagged rocks, Monument Valley has been the backdrop for John Ford films such as Stagecoach (1939), She Wore A Yellow Ribbon (1949), and The Searchers (1956). Arizona has played a familiar role in Gunfight at the OK Corral (1957), 3:10 to Yuma (1957), and Tombstone (1993). Dances with Wolves (1990) showcased the majestic landscapes of the Dakotas, while The Far Country (1954) portrayed James Stewart in Alaska (one of the few westerns to be set there) but was actually filmed in Alberta, Canada.

While the exterior terrain plays a major role, interiors are just as elemental and are quite often created from scratch. The lone homestead on the prairie with its iron stove and checkerboard curtains, the saloon with its squeaky swinging doors, and the prim Victorian boarding house were all designed with both function and history in mind. Take a bar, jail, hotel, “tonsorial parlor,” and mansion of ill repute and you pretty much have the ingredients for a true cinematic western town.

For High Noon (1952) director Fred Zinneman used Western Street A at Columbia Pictures in Burbank as the fictitious Hadleyville, New Mexico, where a lone Marshal Will Kane (Gary Cooper) faces down a gang of killers. Production designer Rudolf Sternad’s Hadleyville earned him an Academy Award for Best Art Direction. Sternad was influenced by the Civil War photos of legendary photographer Mathew Brady, and his vision was wonderfully executed by cinematographer Floyd Crosby. The production was influenced by another factor: Unplanned but atmospheric nonetheless, the famed Los Angeles smog moved in and lasted for the entire 28-day shoot, ultimately lending the film its hazy look.

John Ford’s Stagecoach (1939), which made John Wayne the quintessential western icon, also left an indelible image with filmgoers. Not only was the story of a group of stagecoach passengers traveling across perilous Indian country the first “talkie” western, it was visually striking. Black-and-white scenes filled with contrasts of shadow and light, the sight of a stagecoach meandering minutely along a dusty trail against the mammoth rock structures of Monument Valley — these unforgettable images have made the movie an icon of film design.

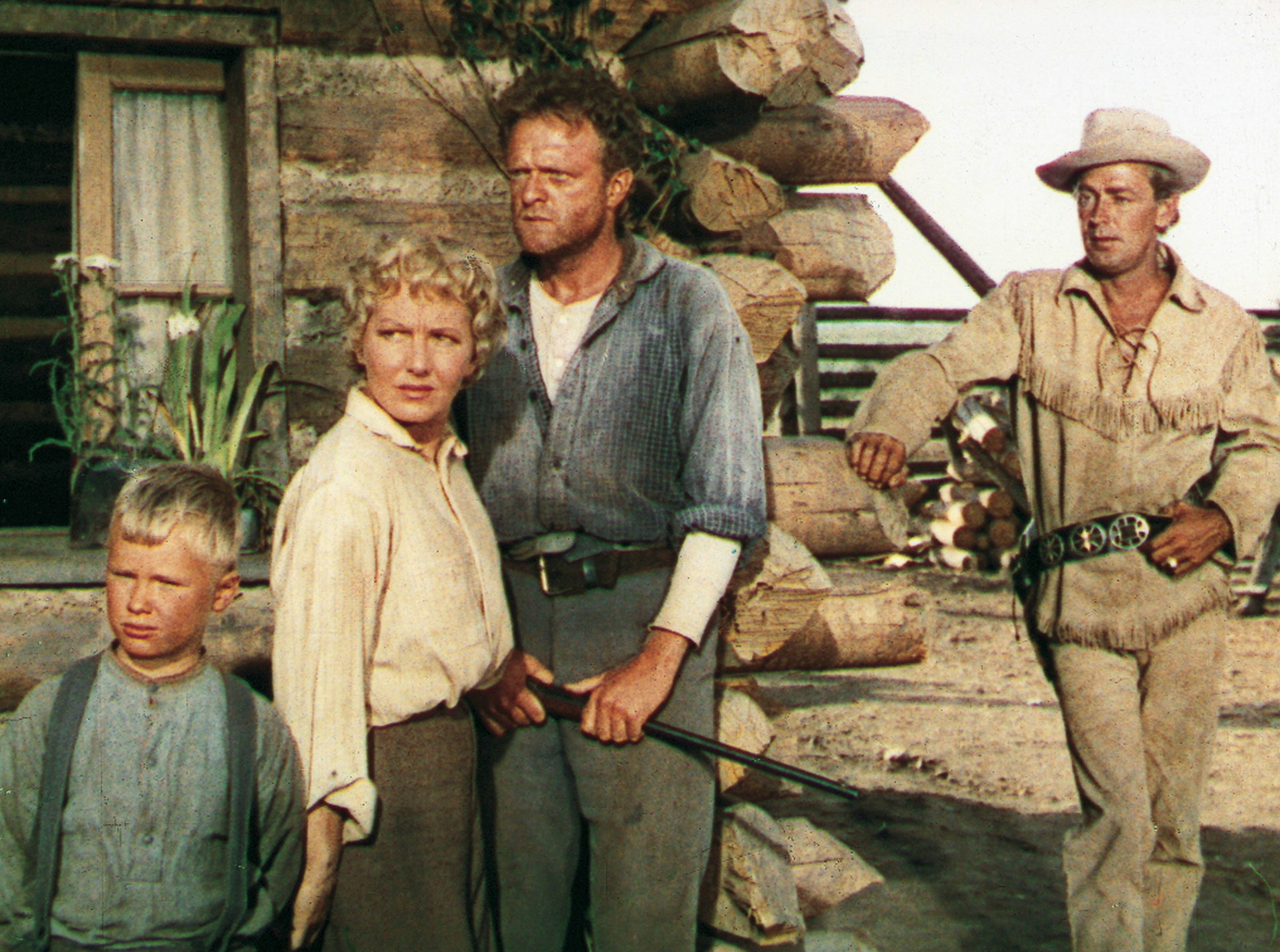

For Shane (1953), director George Stevens created the West of his dreams on location in Jackson Hole. Alan Ladd plays the weary gunfighter who yearns to settle down on the Starrett homestead but is ultimately compelled to leave. With the Tetons as a backdrop, art director Walter Tyler and supervising art director Hal Periera built the town of Grafton to scale to make the story as realistic as possible. Set decorator Emile Yuri had the entire prop department of Paramount at his disposal; his keen eye for detail and use of historical items for the homestead’s decor immediately transport the viewer back to the frontier. The movie culminates in a poignant moment remembered as much for the visual as for the dialogue and the emotion. As Joey (Brandon DeWilde) calls “Shane! Shane! Come back!” the words resound along with the final image of Shane riding off into the sunset and over the mountains. Loyal Griggs won an Oscar for capturing it all with his evocative cinematography.

For Giant (1956), another landmark western directed by George Stevens, production designer Boris Levin scouted numerous locations determined to find a solitary house in the distance that would be a metaphor for the loneliness of the oil-rich Benedict family. Levin found the perfect spot in Marfa, Texas, where the front porch and and front and sides of the Victorian mansion were erected on the desolate plains — literally, just a facade. The interiors and oil derricks were built on the Warner Brothers lot in Burbank, but the audience was none the wiser. The Marfa sets were as grand as the state of Texas and made the perfect backdrop for the roiling epic that set memorable characters immortalized by James Dean, Elizabeth Taylor, and Rock Hudson at loggerheads for generations.

For Academy Award-winning Dances with Wolves (1990) actor-director-producer Kevin Costner wanted a distinctive look and strove for an effect that would be much like a child seeing the West for the first time. Production designer Jeffrey Beecroft studied John Ford’s westerns as well as Little Big Man (1970) and Once upon a Time in the West (1968) along with the archival photographs of Mathew Brady. Filming took place in South Dakota, which had all the needed elements, including hundreds of four-legged extras at the 5,500-acre Triple U Ranch. Beecroft skillfully used a changing color palette to further create atmosphere, beginning with harsh blues, grays, and reds for the opening Civil War sequences. “As we moved west, the color drained out of the landscape and [we used] ruddy browns as opposed to blood red,” he says. Unable to shoot the opening Civil War sequence in the South, the production team built the set in the middle of South Dakota, going so far as to plant a thousand trees (which were painted gold with an orchard sprayer to depict the fall season) and to grow an actual crop of hybrid corn.

Another film that was too massive to be shot on a backlot was Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven (1992). Nominated for Best Art Direction, the film noir western marked the 11th of 13 collaborations between Eastwood and the late production designer Henry Bumstead. For it, the former USC football star turned architect and designer known as “Bummy” built an entire western town (“The Big Whiskey”) in Calgary, Canada, in a record 43 days, the fastest job he had ever completed since Eastwood’s High Plains Drifter (1973). The town had all the western essentials — billiard hall, saloon, hog farm, and bedrooms for the ladies of the night. “We had very little time to build a set and make it look lived-in, so I used all the tricks I knew,” Bumstead said. He even had a trick for what to do after a chinook storm seized the town before filming ended: The production team shipped some of the buildings to California — log by log.

The Coen Brothers’ 2010 remake of the 1969 hit True Grit saw production designer Jess Gonchor and set decorator Nancy Haigh meticulously creating a post Civil War town (Granger, Texas, became Fort Smith, Arkansas) to represent “America on the uprise,” which meant brick buildings with awnings and balconies. Gonchor, who also did the set design for the Coen Brothers’ No Country For Old Men, said his goal was to design a western unlike any he had ever seen and chose to forgo the traditional use of landscape for a very different feel altogether. For their efforts on True Grit, Gonchor and his team were nominated for an Academy Award for Best Art Direction.

“One of the pleasures of movies is creating a world,” director Joel Coen has said. When production design and art direction succeed, the world that’s created can mean the difference between a good movie and a great movie. In the end, it’s as much about transporting the viewer visually to another world as it is about telling a story that resonates in this world. As Joel Coen contends, “Every movie ever made is an attempt to remake The Wizard of Oz.” Even if it does look like the Wild West.

From the January 2013 issue.