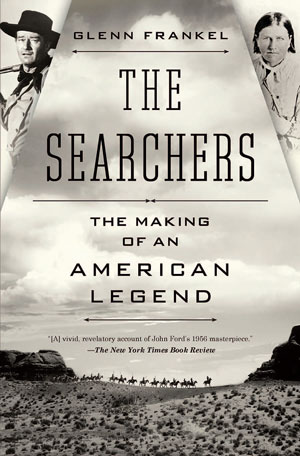

Glenn Frankel’s new book on John Ford’s iconic western film uncovers an incredible history.

Near the end of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, filmmaker John Ford has a frontier journalist dismiss any attempts at historical revisionism by memorably proclaiming: “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” But Glenn Frankel, a Pulitzer Prize-winning former Washington Post writer, takes a more even-handed approach while delving into the stories behind the story in his critically acclaimed book about another classic Ford film, The Searchers: The Making of an American Legend.

Frankel devotes much of his fascinating and multifaceted history to the stranger-than-fiction saga of Cynthia Ann Parker, who was abducted by Comanche warriors at the age of 9 during an 1836 raid on a Texas settlement and raised as a member of their tribe. Nearly 25 years later, Parker was recovered by U.S. Cavalry and Texas Rangers during the 1860 Battle of Pease River. By that time, however, she was no longer the girl her family had long searched and prayed for. Indeed, she considered herself a Comanche — the wife of a warrior and mother of his three children — and came to view her return to white society as a sentence, not salvation.

Throughout the decades following Parker’s death in the early 1870s, her remarkable life and tragic misadventures inspired plays, operas, and fancifully romanticized narratives. In 1954, veteran Hollywood screenwriter Alan Le May drew from the same source while writing his well-received novel The Searchers. The book was adapted in turn by John Ford and scriptwriter Frank S. Nugent into the classic 1956 movie starring John Wayne in his role as Ethan Edwards, the Civil War veteran obsessed with finding his beloved niece after her capture during a Comanche raid on her father’s Texas homestead.

Western fans and movie buffs of all stripes doubtless will enjoy Frankel’s richly detailed account of Ford’s grueling shoot in Monument Valley (the director’s signature movie location) with Wayne and a strong supporting cast that includes Jeffrey Hunter, Ward Bond, Natalie Wood, and Harry Carey Jr. But the story doesn’t end there.

Frankel also details the enduring afterlife of The Searchers, noting how the movie continues to inspire directors not yet born when VistaVision widescreen images of Wayne’s relentless Ethan Edwards first flashed onto theater screens. In doing so, Frankel respectfully acknowledges what, until now, has arguably been the most significant study of The Searchers as a pop-cultural touchstone: critic Stuart Byron’s oft-quoted 1979 New York magazine essay. The piece made the case for Ford’s film as the primary influence for a generation of American filmmakers.

According to Byron, everything from Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) to George Lucas’ Star Wars (1977), from John Milius’ The Wind and the Lion (1975) to Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) contain thematic and/or visual elements that can be traced to Ford’s career-highlight drama of obsession and pursuit.

Frankel doesn’t dispute the accuracy of Byron’s appraisal. In fact, he agrees that Ford’s film continues to be echoed in more recent movies. But as Frankel’s book convincingly demonstrates, the historical facts behind Ford’s fiction are every bit as riveting.

We recently caught up with Frankel at his home in Austin, where he serves as director of the School of Journalism at The University of Texas at Austin, to talk with him about the dual roles of truth teller and tale spinner he filled as the author of The Searchers: The Making of an American Legend.

Cowboys & Indians: It’s amusing to see that even you wind up quoting Stuart Byron’s famous essay about The Searchers. It’s as though that article has become almost as influential as the movie itself.

Glenn Frankel: And have you read it lately? It’s funny now to read something like, “The Searchers is a movie that will never get its full due.” But on the other hand, I guess that’s still a little bit true, in that there are still some people who think of John Wayne as this kind of plodding guy with a toupee who always plays the same part over and over. That’s always been a bit problematic.

C&I: Well, maybe that’s what some whippersnappers might say if they’ve only seen his final few movies. But surely if you look at Wayne’s entire body of work ...

Frankel: Of course. The ironic thing is the John Wayne of The Searchers — and in his movies during the years leading up to it — has a very different feel to him. In fact, I have to admit, it was a revelation for me to go back and see his earlier films, like The Big Trail [1930], at the very start of his career. Or going back and seeing Stagecoach [1939] again and seeing how he developed as an actor after that. Really, he’s a much more charismatic and wonderful actor earlier on. And that John Wayne is one of the reasons why The Searchers is such a great movie.

C&I: What surprised you the most while you were researching your book?

Frankel: One of the things that really surprised me as a researcher is there are probably more documents and readily available information about Comanches and the Texas wars in the 19th century than there is about the inner thoughts of John Ford during his life. John Ford never wrote a book. He left film notes at the beginning of his projects, but he very seldom revisited them in any way. He didn’t do storyboards. And except for conversations he had with his grandson, Dan, toward the end of his life, he didn’t give extensive interviews to anyone. In a way, Ford is very much hiding in plain sight. You just have to look at the films themselves and examine them, because Ford himself is hard to trace. That made researching him harder — but at the same time more intriguing.

C&I: You also focus in your book on Cynthia Ann Parker, whose true-life story inspired Ford, author Alan Le May, and many other storytellers. You obviously uncovered quite a bit about her during your research.

Frankel: Some of the really great finds for me were in the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History. That’s where I found these handwritten notes that two cousins of Cynthia Ann Parker left behind. One was a first cousin who did some research — some reporting, if you will — about 10 years after Cynthia Ann’s death. Susan Parker St. John was her name. She was putting together a sort of family history and actually went back and talked to people extensively. Her notes are mostly in pencil. And they’re scattered in a couple of boxes — there’s no annotation. But they’re marvelously evocative. And they have the ring of truth that so much of the macho, more triumphant histories of the period lack.

C&I: How did you come to be so fascinated by The Searchers?

Frankel: Well, of course I saw it when I was a kid. But the first time I really looked at it as a serious film was back in 1970 at Columbia University. [Film critic] Andrew Sarris was teaching his first lecture course. And since he was an auteurist — someone who considers a director to be the true “author” of a film — one of his goals in life was to sort of redeem great Hollywood films and great Hollywood directors, and cast those filmmakers as artists. He wasn’t interested in westerns, per se. He was interested in cinematic art, and who created it. And his contention was that Howard Hawks and Alfred Hitchcock and John Ford, and a handful of other Hollywood directors, were just as important as Truffaut, Godard, Fellini, and all those other foreigners we venerated as artists.

C&I: And of course you now agree with Andrew Sarris.

Frankel: [Laughs.] Obviously, I’m prejudiced. But I don’t want my book to be just for people who love The Searchers, or love westerns. I want it to be read by people who have maybe never seen it, or haven’t seen it in a long time. And maybe get them to appreciate that The Searchers is a great piece of cinematic art. That’s really what I’m interested in.

C&I: OK, the inevitable question: What is the secret of the movie’s enduring appeal? Why has it remained such a favorite of critics and academics as well as western movie fans?

Frankel: Well, if you remember, Byron had an answer: The Searchers is an important film because it played such a formative role in influencing so many contemporary filmmakers. They all saw it while they were in their teens, or really moving up and thinking about making their own movies. They always talked about it — and you can clearly see the influence of it in so many of their films. It’s constantly being quoted. And that’s been passed on from generation to generation of filmmakers.

C&I: But what do you think?

Frankel: To me, The Searchers is the apogee of Ford’s cinematic art. It’s beautiful. It takes full advantage of the technology of the time, so it’s still stunning to look at. And emotionally, it’s very, very powerful. Because when you boil it all down, it’s really about the triumph of love over hate. That’s very satisfying. And yet it’s not a romantic film. It’s not syrupy. But those last moments are so powerful — you can’t help but surrender to it.

From the July 2013 issue.