Bush pilots, fishermen, tourists, miners, Eskimos, and lawyers mingle in remote western Alaska. And it’s the mighty king salmon that brings all their interests together.

In Alaska, “the West” means something different than it does in other places. Across the state it means “western Alaska,” the most rugged, remote, and unsettled major parcel of land left in the country. It’s the literal embodiment of “frontier,” a word conjured for mostly euphemistic purposes in the rest of the world.

In Anchorage and Juneau (where I grew up) and the Inside Passage, where cruise ships bring floating cities from the Lower 48 every day from spring through fall, Alaska’s whole “last frontier” gambit often comes off like a stale department of tourism pitch. Last frontier? Well, sure, it says so on the license plates ... which you can easily find on all the Hondas and Subarus parked in front of the local Costcos and McDonald’s.

Not so in western Alaska, where just getting to the place requires a crazy airborne epic — two hours in a 10-seat de Havilland Otter that takes off from Anchorage and then floats, bobs, dips, and shimmies for 200-plus miles over saber-toothed glaciers, hostile mountain peaks, kamikaze valleys, treacherous hillsides, suicide waterfalls, man-eating rivers, muskegs, meadows, hillocks, sloughs, and, once every 30 miles or so, some lonesome settlement, a loose collection of outbuildings and oil tanks clinging to the vacant tundra like the last leaves of autumn.

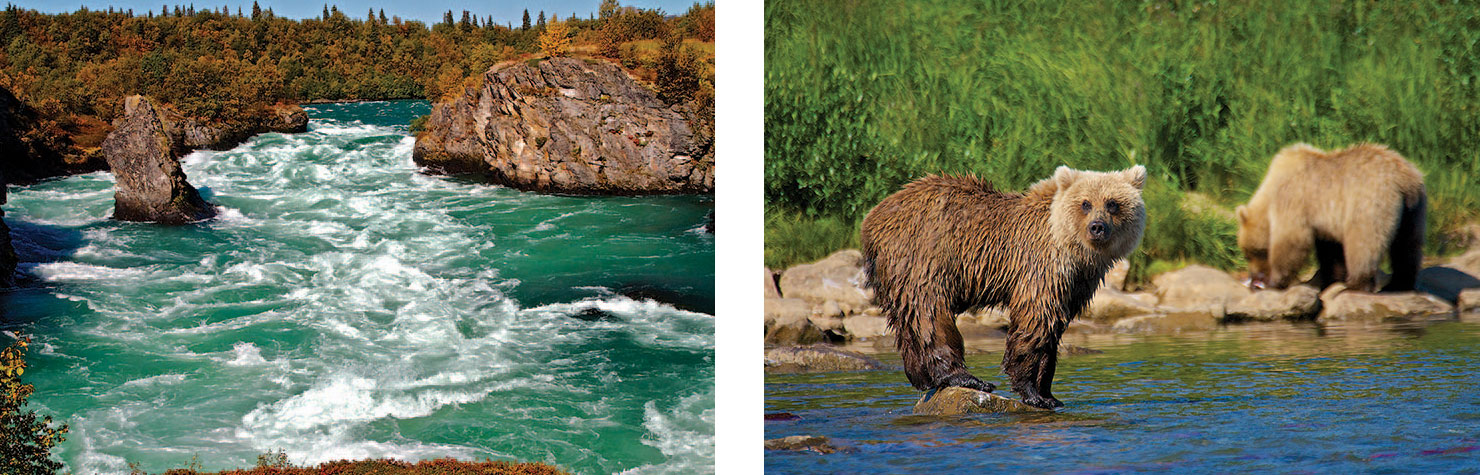

West of Anchorage, the most dramatic wonders are found over Lake Clark National Park & Preserve, a wilderness filled with salmon, bears, and the most majestic body of water you’ve probably never heard of. Lake Clark is the milky-green love child of melting glaciers, the central feature of a landscape so forbidding that few modern travelers will ever set foot in it, though ancient tribes have inhabited the area since the end of the last Ice Age.

You have to fly past this place to get to Iliamna.

God, Country, Family — And Fishing

“I’ll tell you what the problem is: It’s the entire country turning away from God and not wanting to face up to the real world around them.”

This salty observation comes from a miraculously energetic 85-year-old fisherman named Jim Miller. A lifelong Oklahoman, Jim and his retirement-age son, Carl, have been regular visitors to Iliamna for the last 20 years.

The “problem,” as Jim sees it, is the widespread contemporary abandonment of the hunting, fishing, and outdoor lifestyle that’s been a birthright for men of his generation. Before the sit-and-watch ascension of the NFL, NBA, and that foreign spectacle of guys in knee-high socks running around for 90 minutes not scoring any points, rifles and fishing poles defined sport in this country. As Jim, Carl, and a lot of other men over 50 will warn you, when our collective wilderness zeitgeist and skills vanish, so too will an irretrievable part of our unique national character.

As the kind of guy who gets antsy when strangers start talking about God wanting us all to own personal firearms, you might suspect I’d be quick to dismiss Jim as a rabid reactionary. But I’m not.

For one thing, I agree with a lot of what he says. For another, it’s hard not to like an 85-year-old guy from Oklahoma who has a folksy Will Rogers facility with the English language.

The day I meet Jim, we’re fishing for king salmon in an open skiff on a cold and wet morning on the Nushagak River. He flashes his optimistic flatland wit when assessing a cranky sky that seems almost ready to surrender a temporary clear patch: “Well, boys, it looks like it’s going to stop raining some more.”

Jim and Carl are guests at Rainbow King Lodge in the Native village of Iliamna (population 109). The town rides the banks of Lake Iliamna, one of only two lakes in the world with freshwater harbor seals. These are not to be confused with the Iliamna Lake Monster, or Illie, as locals call the rumored beast that inhabits the lake, ostensible sightings of which have haunted Native tales and prompted a visit from Animal Planet’s River Monsters.

Rainbow King is a fascinating outfit. Comfortable and equipped with everything from ESPN to a world-class chef, it’s nevertheless not as gaudy as the four-star luxury lodges scattered around western Alaska. It’s a “real deal” throwback fly-out lodge from the glory days of Field & Stream. As its name suggests, this place is all about the fish. Though novice fly-casters are welcome and soon brought up to slaying speed by a crew of first-rate guides — “You want to learn a double-fisted whip cast? No problem!” — its top customers are the types who place fishing somewhere very high in the pecking order of God, country, and family.

“It’s a first-class operation. They do everything right,” says Carl when I ask why he and his father keep coming back to Rainbow King. “If it can be done, they’ll do it for you, and if it can’t be done, they’ll have someone working on it,” Jim chips in with his irresistible Sooner drawl.

Like Jim and Carl, more than half of the lodge’s customers are repeat visitors. A lot of that has to do with the staff, but a lot has to do with the fishing, which is stone-cold ridiculous out here. On good days, Iliamna feels like a place out of those sourdough tall tales featuring streams so full of fish that you could walk on their backs from one bank to the other without getting your boots wet. My first day in Iliamna, less than 15 minutes after my first cast into Fog Lake, I pull in two pike and then, in the nearby Copper River, the biggest rainbow trout who’s ever had the honor of having his picture taken with me.

Because it’s one of the more established lodges, Rainbow King has longstanding deals with the local Native corporation that give it exclusive access to some of the area’s best fishing spots. At a secret hole called “the Gorge” my luck isn’t quite as strong as it was on Fog Lake (meaning it takes about 30 minutes before the graylings start jumping into my net), but that’s a small nuisance considering the surroundings. At the head of a placid pond, cloudy jade glacial runoff barrels down a set of steep falls through a rock-walled salmon stream, creating a perpetual geyser of churn, foam, and mist.

“When I die, bury me at Lion’s Head,” says my Rainbow King guide for the day, indicating the gorge’s most prominent rock feature. It’s this kind of aside that makes a guide a good fishing companion. Focused on casting, I haven’t really stopped to look closely at the outcropping. When I do, I see that from the right angle, it really does look like a lion — and, not incidentally, a reasonable place to be buried.

The Cost Of Fuel And The Endangered Bush Pilot

It’s almost impossible to get your head around Rainbow King Lodge’s fuel bill. Not that you’re thinking about that when you’re gaitering up for a day of fishing for king salmon. But compute the cost of flights from Anchorage to Iliamna and daily bush flights in small aircraft from Iliamna to otherwise inaccessible rivers, lakes, and streams at fuel consumption rates that make a Hummer seem fuel-efficient, and you begin to understand the expense of high-end wilderness travel.

With aviation fuel at about $8 a gallon and a Beaver float plane sucking down 25 gallons an hour and an Otter guzzling 40, it takes a group of guys with special interests and special resources to get out to the frontier we’ve pushed so far away in this country. Besides being avid fishermen who will go a great distance to have the best experience and pass the tradition from father to son (or daughter), Jim and Carl can go to great expense: They’re bankers.

Jim, Carl, and I take one of those Beaver flights to a fishing camp an hour west on the Nushagak River, into which all five species of Pacific salmon — king (chinook), coho, sockeye, chum, and pink — spawn. The view from the air is the kind of beautiful that just shuts you up and makes you not want to bother insulting The Landscape by trying to take pictures with your crummy little camera. Better just to silently take it all in, fuel burn the furthest thing from your mind.

Our pilot, Jack, is a scruffy, heavyset guy in his mid-50s. He sets us down on the choppy river like he’s placing a Ming vase on a sheet of Tiffany glass.

Arriving at the fishing camp from the bustling metropolis of Iliamna feels like being dropped into a forlorn cavalry outpost from the Kansas Territory. Split log fires burn in front of white canvas tents that flap in the breeze. At similar camps up and down the riverbank, the stars and stripes fly from the tops of makeshift wooden flagpoles.

There’s food ready when we wander into camp courtesy of Jerry, another 50-something who also flies bush planes. Jerry pulls double duty as chief cook, bottle-washer, and utility man for hire. He learned to cook in the Army, which he says explains why he puts enough food on a plate to drop an adolescent mastodon into a food coma.

“All my recipes are in gallons and pounds,” he says cheerfully.

This sounds plausible, though Jerry’s Army background doesn’t explain why his scratch beef stew, grilled salmon, fried potatoes, and warm oatmeal cookies are so damn good.

“You can’t get young guys to come out here anymore and do anything and everything,” Jerry says, lamenting the endangered virtues of the well-rounded bush pilot. “To do this job you gotta be able to chop wood, gut fish, cook, haul gear, mend a wound with needle and thread, and fly a plane. When we started out flying, you had to do all that for $900 a month.”

“Now they just train pilots to work for the airlines,” Jack grouses. “The young guys are great with programming GPS, but they don’t really have a feel for the basics ... stall, flap, dive ... real bush pilots are dying out.”

Jerry responds with a whaddya-gonna-do expression. Jack is more of a curmudgeon — plenty of dirt beneath those fingernails and enough open resentment of modern society to come off as a little bit crusty.

A few days later, I’ll sit in the copilot seat of a single-engine Cessna 206 flying east out of Iliamna. Next to me is the kind of pilot Jack is disenchanted with. Nate is a 32-year-old from Nome by way of Ohio who flies for a tiny charter and local service outfit called Lake Clark Air. He’s thin, cleanshaven, wears a beaded necklace, and is outgoing to an almost nerdy degree. He refers to fishermen in the camps as “mosquito feeders” and compares a huge boulder field on top of a glacier to chocolate chips.

When we land in Port Alsworth (population 159) to drop off a teenage girl and her uncomplaining husky (both ride comfortably in the back seat), I ask Nate about what it’s like being a pilot in Alaska’s treacherous interior.

“I never tire of the flights here,” he says. “I’ll turn around and go back from Port Alsworth to Iliamna tonight and it’ll be all different — light, clouds, snow, mist. You see something different every time. The good Lord deserves a round of applause for all this. I’m just blessed to have an office window like the one I have.”

I come away from the flight with greater hope for the new generation of bush pilots than Jack had given me. Nate might not yet have the Ming-vase skills of some of the older guys, but he clearly knows his way around more than just a GPS tutorial.

Battle On The Last Frontier

Like the bush pilots, western Alaska’s King Kong scenery won’t be going away anytime soon, but there are worries that its extraordinary fishing might. Near Iliamna, an enormous international mineral exploration project called Pebble Mine is underway. Vast deposits include copper, gold, and other minerals worth an estimated $350 billion.

Still in the study and pre-permitting phase, the future opening of the mine is already being vigorously opposed by groups who believe that mine tailings and waste rock — an estimated 10 billion tons — will disrupt the entire Bristol Bay watershed, with lethal effects on the area’s salmon and other fisheries. Robert Redford has attached his name and environmental outrage to the fight. In a Huffington Post blog editorial, he cites a long-awaited EPA study that confirms the Pebble Mine “would spell disaster for Bristol Bay, its legendary salmon runs, its pristine environment and its people.” During the month I was in Iliamna, a group called Renewable Resources Coalition bought the back cover of Alaska magazine to advertise its opposition to the project.

“All of this fishery could be gone in a hundred years due to the mine,” a contract worker in Iliamna tells me. According to Redford, who has been battling the Pebble Mine alongside the Natural Resources Defense Council since 2010, “an overwhelming 80 percent of Bristol Bay’s residents — including its Native peoples and commercial fishermen” — oppose the project. But most of the locals I meet seem to shrug off the notion of an impending mining calamity. Yes, you see the Pebble Limited Partnership logos on shiny pickups around town, but the mine is years away from opening and so apparently not an immediate concern to residents.

Connected to Iliamna by a 5-mile road, Newhalen (population 189) is a village of Yup’ik, Alutiiq, and Athabascan Alaska Natives on the banks of the Newhalen River, a place where the contemporary nuisances of earthmovers and environmental lawyers filing their 9,000th appeal feel eons away.

“Last night, two big bears crossed the river right here in front of my house,” a soft-spoken 60-year-old Native named William tells me. “Half the village came out to watch. They come up the bank of the river all the time looking for fish.”

I approach William as he’s pulling a pair of king salmon out of a set net on the beach and force a conversation. This isn’t easy. There isn’t a ton of interaction between the Natives and transient workers from down south. When I ask one of the white workers in Newhalen what he knows about the Natives he says, “They’re out here doing their subsistence thing, just existing, not much else.”

William doesn’t exactly scoff at this — Natives in Alaska aren’t known for confiding in interlopers — but clearly he does more than exist.

“I just got back from New York visiting my mother,” he tells me. “I don’t like it there — too many people. Italy is better.”

The median household income in Iliamna is $112,650. A for-profit subsidiary of Iliamna Natives Limited, the Iliamna Development Corporation is a busy and successful enterprise.

Fishers Of Men

Iliamna is a “damp” town, meaning you can have alcohol and consume it, but you can’t sell it. There are no bars and no restaurants that serve alcohol. Actually, there are no restaurants.

Guests at lodges like Rainbow King have to bring in their own booze. At dinner someone usually breaks out a nice bottle of wine or a sixer of fancy beer. While I’m at the lodge, a group from California arrives and lines up 12 bottles in the dining room to have with their meals.

A devout Gideon, Jim doesn’t drink, but after dinner on my last night he tells me he has a gift for me. First, though, he wants to continue our conversation, not about fishing but about his mission traveling the globe spreading the Word.

“There’s a warrant for my arrest in Vietnam for trying to reestablish the Gideon word in Vietnam so Bibles could be distributed through underground Christian churches,” he says. “I got out of there by the hair on my teeth.”

Jim is concerned about my eternal reward. He reaches into his gear bag, fishes out a pocket-size New Testament with a brown Leatherette cover, and hands it to me.

“It’ll keep you good company at the end of the world,” Jim says.

I take the mini-Bible, shake his hand, and head out the door. A Ford Econoline van taxi with a few dozen dents and a factory cassette deck still in the cracked dash is waiting. By the time the double-edged logic of Jim’s folksy farewell hits me, I’m at the little airport outside of town, folding myself into another tiny aircraft, putting my life in the hands of another frontier flier, turning away from one end of the world and heading back to the other, one way or another taking a little piece of Jim’s deliverance with me.

Names have been changed to preserve anonymity. For more information about the lodge or to make reservations for the June to September season, visit Rainbow King Lodge’s website.

From the May/June 2013 issue.