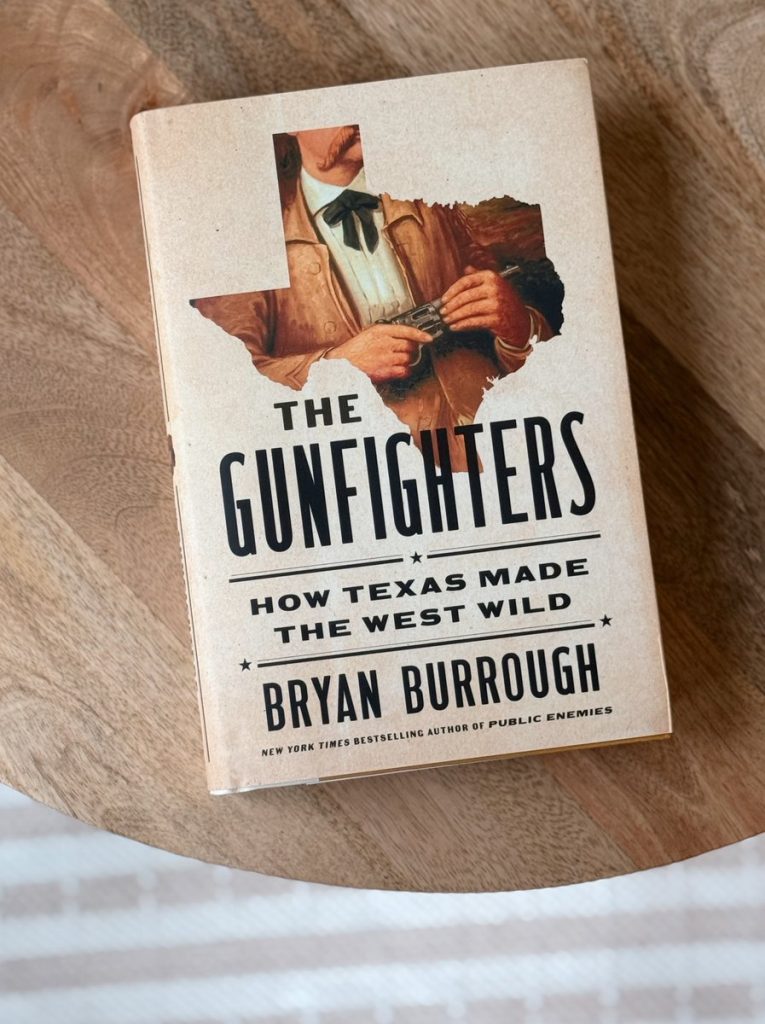

Bestselling author Bryan Burrough reveals the real stories behind the Old West’s most infamous gunfighters—and why their legacy still grips the American imagination.

In this episode of Writing the West podcast, we sit down with journalist and historian Bryan Burrough, author of the riveting new book The Gunfighters: How Texas Made the West Wild. Known for his bestsellers Barbarians at the Gate and Public Enemies, Burrough brings his sharp investigative lens to the gunfighter era, tracing its roots in Texas honor culture, post–Civil War violence, and the rise of Western mythology. From Wild Bill Hickok to Wyatt Earp and lesser-known legends like Pink Higgins and Luke Short, Burrough explores how these men became the American archetype of rugged individualism—and how their stories continue to shape pop culture today.

(This interview has been edited for length and clarity).

Cowboys & Indians: You’ve written about everything from Barbarians at the Gate to Public Enemies—what led you to the American West and to writing The Gunfighters?

Bryan Burrough: It was really the process of writing Public Enemies, which a few people may remember from 20 years ago. More people may be familiar with it as the Johnny Depp–Christian Bale movie from a few years back. But writing about gangsters and bank robbers and outlaws in the 1930s—and talking about how they came about—obviously makes you glance back at the last time people with guns attracted fascination from the American public.

Look, I got my first gunfighter book—I don’t remember which one it was, I think it was Billy the Kid—when I was 11. So I had been reading about it for a long time. But it wasn’t until then that I really began to think of it as something I wanted to do next. The problem was, I couldn’t come up initially—this was 20 years ago, back in ’04 or ’05—I couldn’t come up initially with a way to tie it all together. I didn’t want to write one more of those books—and some of them are okay—that has 17 chapters on 17 gunfighters. I wanted to tell the whole story as a single story. It took me off and on over 10 years to come up with a way to do that. I worked on this book off and on for seven years.

C&I: What made the gunfighter the focal point for you, out of all the possible Western subjects?

Burrough: It was not the West that drew me. It was the gunfighter that drew me to the West, rather than the West drawing me to the gunfighter. The first thing to understand when writing a book is that you're withdrawing into a room—physically, literally, and emotionally—for five years. So you'd better be fascinated by the topic. And I was.

So the question became—look, I set my bar pretty high. The publisher expects it. People who’ve read my books expect it—that if I’m going to go into a new field, I’ve got to say something big. I’ve got to, in my mind, reimagine the field. I’ve got to really contribute something. So it just took me a while to figure out what I could do in the field of gunfighters—which people have been writing about for 150 years. What could I do that felt fresh and new and reimagining? And I like to believe, obviously, that I’ve done that. We’ll see if your readers agree.

C&I: You’ve written on both contemporary and historical subjects. Did your process change at all when researching and writing this one?

Burrough: Yes and no. I mean, look—this is my eighth book. My first five or six were classic, top-down, serious, research-heavy books. Something changed on the last book I wrote four years ago, called Forget the Alamo. In an effort not to alarm or upset Texans, I wanted the book not to be preachy, because it was advancing alternate ideas about the Alamo and the creation of Texas. So I really wanted it to be—what I kept saying—a friendly book. Conversational. Not “important author,” but more like a guy you were sitting down to have a beer or a cup of coffee with.

And I found that that voice was natural to me. I just wrote the way I talked, and people responded pretty positively. So I decided that’s what I wanted. That was the first thing I wanted to do with Gunfighters—make it friendly and accessible and easy for people. I’m forgetting your question, but I hope I answered it.

C&I: You did. And your opening scene—the Hickok–Tut duel—immediately hooks the reader. Why begin there?

Burrough: If you’re just a layperson sitting in your car, you think “gunfighters,” and it’s this enormous subject—hundreds of these people, or at least dozens. How do you make a single story out of that?

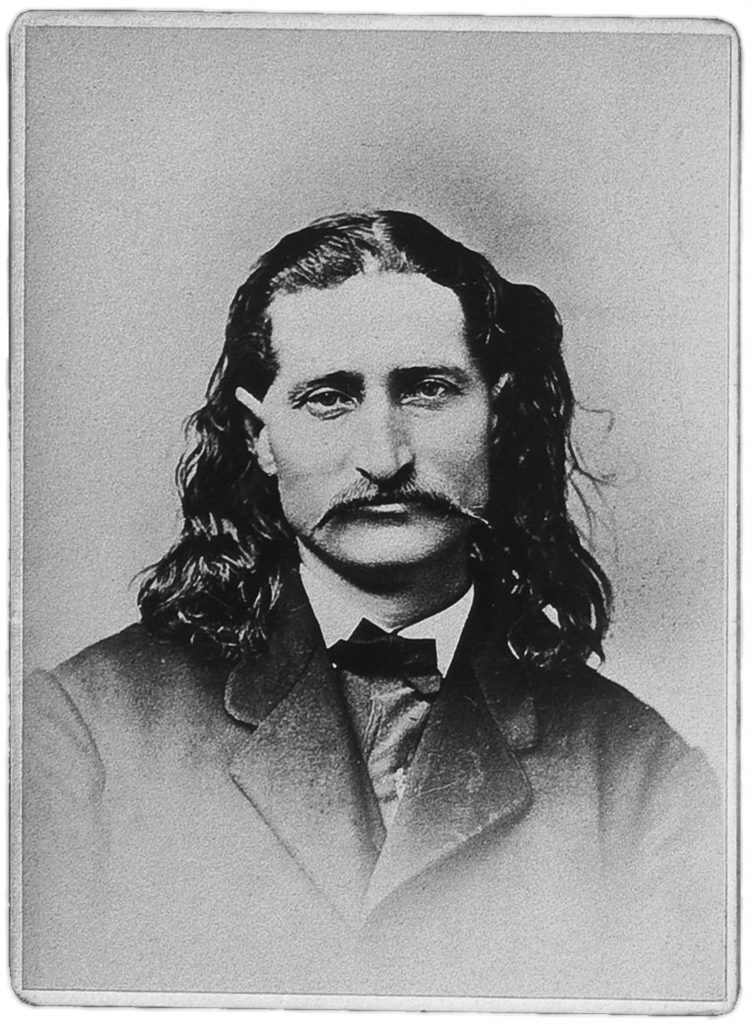

Well, the wonderful thing about the gunfighter era, as I’m calling it—from 1865 to 1901—is that it has a beginning. And that is the Cock–Tut gunfight. It was not, as some would have you believe, the first Old West gunfight—but it was the first Old West gunfight that attracted national attention after the Civil War. So I thought, wow, that is the natural place to start.

Now, as you no doubt know—and as aficionados no doubt know—a lot of Western histories tend to talk about gunfighters only after the Civil War, and they leave out entirely the 10 years of kind of manic gunfighter violence in Gold Rush–era California. So I do back into that—I don’t forget California—but I really treat it as a kind of prologue. I’m trying to write what I view as the first narrative history of what I’m calling the Gunfighter Era, beginning with Hickok and Tut in Springfield, Missouri, July 29, 1865. And the story ends when Butch and Sundance get on that freighter in Brooklyn for South America in 1901. I thought I could make that work.

C&I: Why does that 1865–1901 window define the gunfighter era for you?

Burrough: Well, you’re right that it’s arbitrary. I’m the one defining it as the gunfighter era, so that’s fair. But look, 1865 to 1901 encompasses the beginning and the career of everyone you’ve ever heard of. From Billy the Kid to Wild Bill Hickok, to Wyatt Earp—none of them were shooting people before 1865, and none were doing it after 1901. Of well-known gunfighters, I’d say Frank Hamer, the Texas Ranger, is one of the few whose career extended past 1901.

But I knew I wanted to include Butch and Sundance—even though they’re more outlaws than gunfighters—because it felt like their story belonged in the book. And what better way to end the story of this era than with the last brand-name outlaws literally fleeing the country? It just felt like a natural place to end. I make it very clear: gunfights went on, bank robberies still happened. But after 1901, you get a sense that the frontier had closed—that this was all moving from headlines to history.

C&I: In the book, you describe gunfighters as America’s Achilles, Thor, or Lancelot. What about that archetype felt uniquely American to you?

Burrough: To me, it all came down to—what’s the principal allure of the West? And when I drilled down into it, after reading a lot of smart academics—a lot smarter than me—it really came down to American worship of individualism.

You can look at a lot of things that make the American character unique, but when you compare it to the German or Swiss or Austrian or Libyan character, a lot of it has to do with individualism. And I suspect that one reason—not the only one—but a key reason the West, with all its myths and facts, remains so appealing is because the frontier years were a unique period for the American as an individual.

Back East, you had politicians and preachers everywhere, and lots of rules and laws. But the fact is, men shot each other on the streets every day in Boston and Baltimore—and nobody remembers them. But when they did it in Abilene or Tombstone, we remember them. I think a lot of that has to do with American reverence for individualism.

C&I: Were you surprised by how short the gunfighter era was compared to its long-lasting legacy?

Burrough: The reviews so far have been very generous, and that’s something a couple of people have said surprised them—that all these gunfighters were out there during the same 35-year stretch, or at least overlapping during it. It didn’t surprise me at all.

Like you, I’ve been reading this stuff since I was 11. I never really thought about gunfighters before the war. I certainly didn’t think about them after 1901—or at least not until the Depression-era bank robbers of the 1930s. So no, that didn’t surprise me. I’m surprised people are surprised. Because if you love the West, this is the water you swim in, right? I’ve been swimming in this water a long time. I get every new book that comes out.

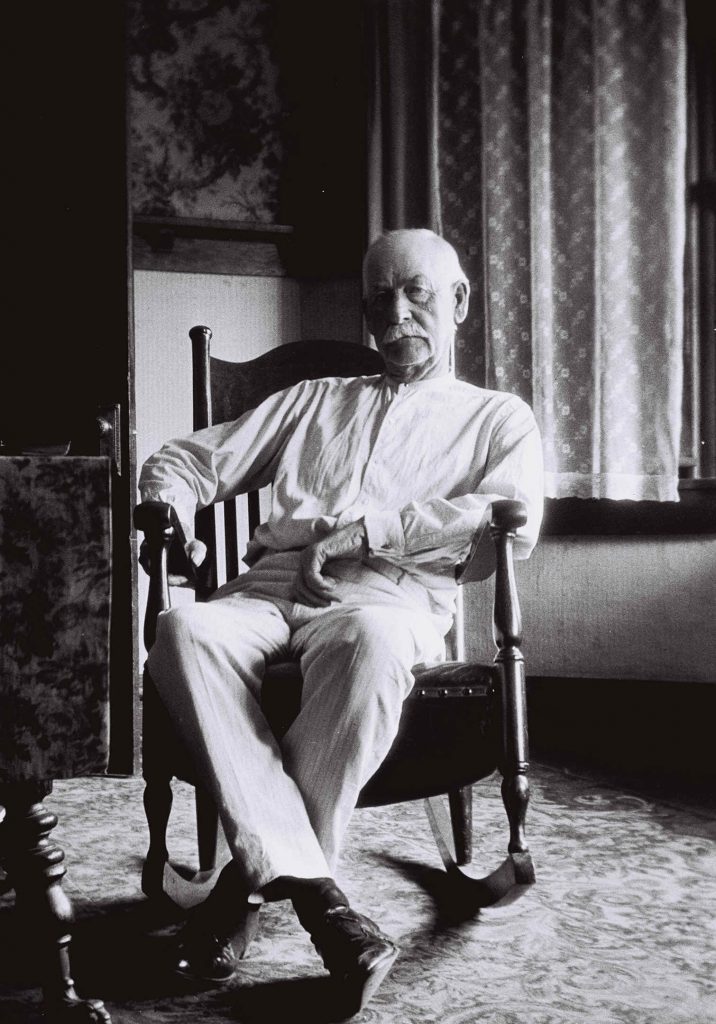

Wild Bill Hickok

C&I: One of your big arguments is that the gunfighter was, in many ways, a Texan. What made Texas such a breeding ground for them?

Burrough: That ended up being a major theme. If Bryan Burrough’s going to try to write a book about an entire era, there has to be something that links these gunfighters. And to me, it had to be behavioral, since their individual stories are so different.

The question became: Why did this culture of gunfighters emerge in the Old West? Why did it fascinate us? And more importantly, was the Old West really as violent as it appears in the movies? The answer: yes, absolutely. We know that now thanks to 21st-century data science.

And if you accept that, the first thing that hit me was, “Holy God, there were Texans in seemingly every major gunfight!” I didn’t understand that at first. But then I realized I had to understand the behaviors that led to gunfighting. I traced it to the antebellum South—the dueling culture, the importance of male honor. Texas was every inch a Southern state.

What really changed was the immense violence that broke out in Texas right after the Civil War. From 1865 into the mid-1870s, Texas was a proud place that had not been conquered during the war—it was only occupied afterward. That sparked two big waves of violence. First, a backlash against the occupation. Second, the rise of the cattle industry—the first great business of the Old West.

Because it was open range, cattle ranching was especially vulnerable to theft. So Texas cattlemen got good at stopping, killing, and lynching rustlers. That wellspring of violence in Texas, I argue, broke across the West. And the first step in that spread was the cattle trails—the Chisholm Trail and others. That’s why those Kansas cow towns became, as I put it, the Madison Square Garden of the gunfighter era.

C&I: Beyond culture and honor, did these men have anything in common personality-wise?

Burrough: I wanted to be alert to that. But one of the things I liked most is that, while we can generalize about the behaviors that led to all these gunfights—the primacy of male honor and so on—each of these guys is startlingly different.

There are gunfighters you might like, maybe even want to have a beer with—Bat Masterson, Wyatt Earp. I think they were pretty great guys. John Wesley Hardin, for instance? Probably not so much. I think he was pretty much a maniac.

One thing I wanted to avoid was turning them into cartoon characters. If I’m going to be credible, I have to retrieve them as men—as real people. Like most men, they had good qualities and bad ones.

A few commonalities: maybe a quarter of them were diehard rebels—Jesse James, Hardin, Doc Holliday—people deeply marinated in Southern traditions who didn’t take to Yankees, especially Yankee sheriffs. That was especially common early on. But beyond that, it’s hard to generalize. Many of them were outlaws, obviously, and didn’t care for the written law. But personality-wise? Everything under the sun.

C&I: We’ve talked a lot about the Civil War’s influence. How did service on either side shape who these men became?

Burrough: I can cite a few things. One, obviously, is the lingering bad blood between Southerners and Northerners. That clearly contributed to some of the gun violence we saw—especially some of the gunfights in Kansas.

There’s also been some writing in the last 20 years—Smithsonian had a great exhibit—about PTSD after the Civil War. So you at least have to consider that some of these gunfighters who were veterans were suffering from PTSD. You can’t prove it, but we know, for example, Clay Allison, the New Mexico gunfighter, was discharged in part because of episodes he had. I speculate that Ben Thompson, the famous Texas gambler and gunfighter, showed a lot of behavior that feels like PTSD. But that’s just speculative. You’ll never be able to prove it.

What you can point to, though, is the incredible change in the use of personal weapons. In the 1860s, after the war, a lot of men returned home with guns—but even more got guns because the federal government auctioned or gave away 1.3 million sidearms.

You see it a lot in memoirs written during or about that period. Open carry wasn’t unheard of in the U.S. before, but it became much more prevalent in the years after the 1860s. The whole nature of violence changed. Dueling, for instance—once everybody has a revolver—kind of goes away. One of my favorite memoirists said that even grappling, wrestling, and fistfights diminished, because, as he put it, “Those things are now handled much quicker—with guns.”

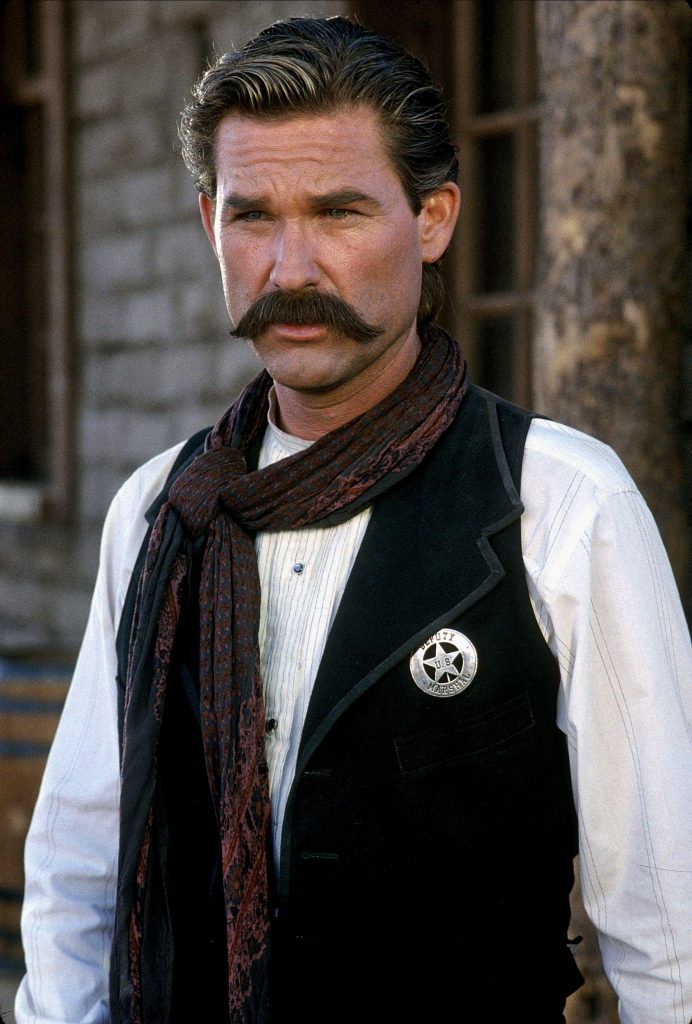

Kurt Russell as Wyatt Earp in Tombstone

C&I: You mention that many of our ideas about gunfighters were shaped by Hollywood. How accurate have those portrayals really been?

Burrough: It’s like asking about portrayals of doctors, lawyers, or journalists—some are good, some are bad. I’d say that over time, movies have generally gotten more accurate. That’s thanks in part to the internet and to individuals out there who care about these details.

The gunfighter didn’t become a popular figure until silent films. He was really rediscovered in the 1920s. The first 30 or 40 years of Hollywood westerns were usually less accurate than what we’ve seen in the last 50 years. Starting in the 1970s, you begin to see films make a real effort—like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, which is maybe 80% accurate.

I think Tombstone, the Kurt Russell one, is great. Even the Kevin Costner Wyatt Earp movie—which kind of puts me to sleep—was pretty close to accurate.

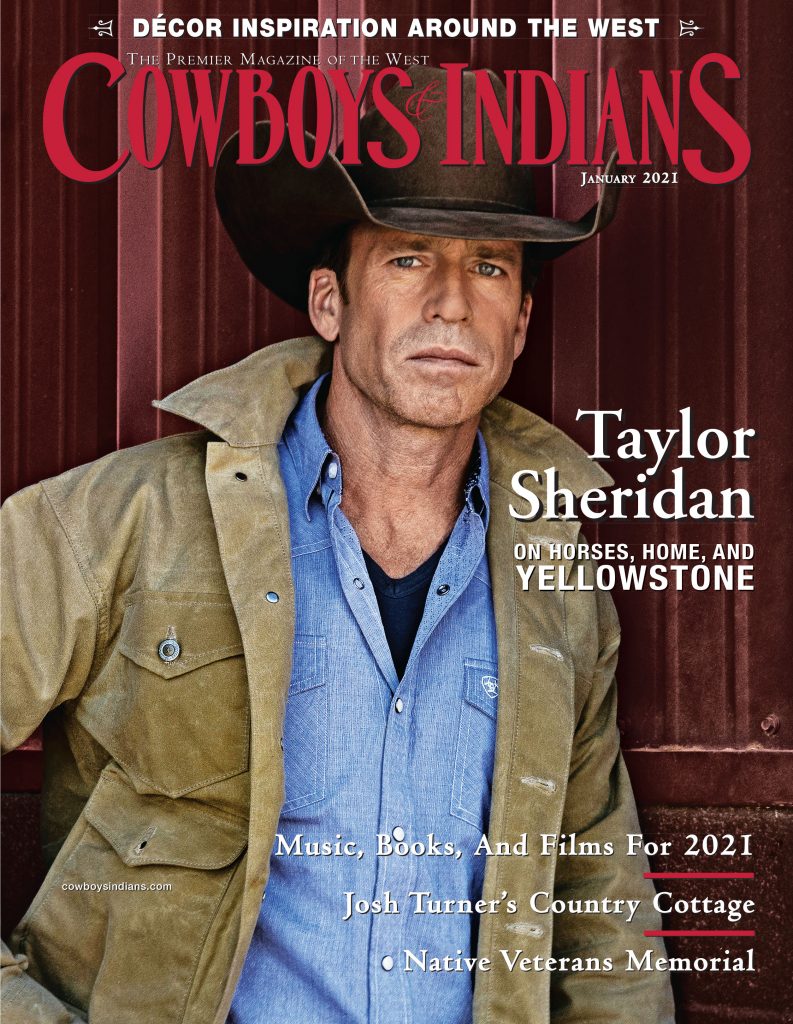

The sad thing is, as westerns got more accurate, they also became less popular. There just aren’t as many now. I think a lot of those old western stories are being told elsewhere—often in outer space. That said, I do have to tip my hat to what Taylor Sheridan is doing today.

C&I: One common myth you mention is the quick-draw duel. What were real gunfights like?

Burrough: The fast draw was first written about and popularized in a book from the 1930s. Then, yeah—Texas, Hollywood, and especially television in the 1950s really ran with it.

We know from Hickok’s own comments—and from Herb and Ben Thompson—that the best gunfighters didn’t prize speed over accuracy. In the Hickok–Tut gunfight that opens my book, Davis Tutt does the thing you see in every bad movie. From 70 yards, he pulls and fires from the hip. That’s not an accurate shot.

Hickok takes a split second longer. He thrusts his left arm forward, places the barrel of his Navy Colt across his left forearm, aims, and shoots Tutt in the chest. From what Hickok, Thompson, and Earp said, you can tell that accuracy mattered more than speed.

If you look at the shootout near the O.K. Corral, those cowboy gang members died mostly because they did the same thing—fired from the hip. Earp and Doc Holliday took just a second longer to make sure their bullets hit.

All that said, a formal gunfight like Hickok and Tutt’s—where two men square off in the street? That was actually pretty rare in the West. You can maybe find a dozen true examples like that.

What you saw a lot more of were saloon arguments that escalated. One guy would say, “Let’s take this outside.” That’s really just an informal invitation to a duel. So even though Westerners had less appetite for formalities than Easterners, you can still hear echoes of the Old South dueling culture in that behavior.

C&I: You suggest that reputation played a major role—that these men were risking their lives over words. Why was honor so important?

Burrough: Yeah, I’m like you. When you look at what triggered the gunfight on Fremont Street in Tombstone, it was just arguments. Really? You’re going to shoot each other over that?

And the only way I can really understand it is to believe that, at that time, especially in rural and frontier areas, the way American men measured themselves was by honor—or respect. That was the currency.

Not many people were rich. One cowboy wasn’t going to be that much richer or more educated than the next. So how do you measure status? I remember how we did it on the playground in elementary school—it was who was tougher. Who was scarier. Who was the bully. I think that’s what you saw in the Old West.

Billy the Kid

C&I: Today, we mostly admire gunfighters in hindsight. But were these men admired in their own time?

Burrough: Great question. It’s something I’ve always found fascinating—how big a deal were these people during their own time?

As a group or archetype, the term “gunfighter” dates back to 1874—the first time anyone’s found it in a newspaper. The idea of a man who’s famous for killing people really started with Hickok. It was created for him in a magazine article back East.

So, yes, people knew who Hickok was. They knew Earp. But mostly, they were regionally famous—not nationally.

And while we often roll our eyes at Easterners writing dime novels, let’s be clear—these figures were biggest in the places they lived. As John Boessenecker and others have pointed out, gunfighters weren’t a huge deal in 19th-century fiction. If you go back and read dime novels, they’re mostly about Indian fighters and detectives. Gunfighters might rank fifth or seventh in terms of archetypes.

It really wasn’t until the 1920s that the gunfighter was rediscovered. One magazine article even opened by asking, “Who remembers Billy the Kid?” That was in 1925. It kicked off the rediscovery of the Old West in books and, eventually, in Hollywood.

C&I: We recently spoke with George Matthews, who wrote a biography of Billy the Kid. He noted that many people in Billy’s own time saw what he did as justified. Did you find that with other Texas gunfighters too—or were most seen as dangerous outlaws?

Burrough: The reputations were all over the place. But what’s interesting is, when you think about it, a gunfighter—to be successful—has to kill people. So you’d think these people were constantly being arrested and put in prison. But you’d be wrong.

There was a legal doctrine at the time—what we’d now call “stand your ground”—and also, certainly, a broad American belief, especially in rural and frontier areas, that it was okay for a man to defend his honor with deadly force.

So you see a lot of these guys getting arrested over and over. Ben Thompson, down in Austin, was arrested a half-dozen times. He got off every single time.

It was unusual for a gunfighter to get put away. One of the few big names who did was John Wesley Hardin—he got 25 years, served 17. Another was Wild Bill Longley, once considered the second most famous Texas gunfighter. He’s since been exposed as a fraud, but he was one of the few to go to the gallows. Tom Horn in Wyoming was another.

But especially in the early years—the 1860s and ’70s—you didn’t see many consequences for all the killing.

C&I: Gunfighters had little economic or political power in their time, yet they’ve become central to American identity. Why has the myth endured so strongly?

Burrough: Well, part of it is that the gunfighter isn’t a new concept. If you think back to literature and entertainment in Europe and Asia, what is the gunfighter but a 20th-century American version of the samurai or the Russian Cossack?

Many older cultures have stories built around lone men of action. That’s the first part.

Then you have America’s fascination—its worship, even—of individualism. Before the gunfighter, we were fascinated with the frontiersman. That began with James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales, then moved into nonfiction with the celebrity of guys like Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone.

All of that set the stage for the rise of the gunfighter archetype.

C&I: What’s interesting is that the gunfighter is such a lone figure, even though the country was trying to come together again after the Civil War. Do you see any contradiction there?

Burrough: I think the key here—and I want to be clear, the book doesn’t get near politics, and I don’t want to either—but just looking at facts: there is no greater equalizer in the world than a gun. If you’re under threat, and you have a gun, you can be any size, shape, or color—and you’re equal.

Unless one guy’s got a machine gun and the other has a .22—but generally speaking, the gun is a great equalizer. And in a country where the American Dream says any man or woman can make it on their own, I think the idea of a gun making people equal appeals to us.

C&I: You’ve written Public Enemies and explored more modern outlaw stories. Did that earlier research influence how you viewed the gunfighter era?

Burrough: Definitely. There’s a fascinating transition period between 1900 and 1930. There weren’t a ton of famous rural criminals during that stretch, but they existed.

You had people like Henry Starr in Oklahoma—he started off robbing banks on horseback and ended up doing it in cars. That’s just incredibly cool to me. I’m probably never going to get a whole book out of it, but it’s cool.

In some ways, I’m still that 11-year-old kid fascinated by cops and robbers. I wrote about them in Public Enemies. I think I wrote about them pretty well in Gunfighters. And a few years ago, I wrote about radical groups bombing things in the 1970s.

I like big, intricate stories of good and evil—or people in conflict. I should probably write war books. But I haven’t yet.

C&I: One thing I loved about The Gunfighters is that it includes men on both sides of the law—like Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson. Some even crossed between outlaw and lawman. What did your research reveal about that side of the story?

Burrough: Every book, when you finish, you look at it and think, “If I had one more chapter…” For me, that chapter would’ve been about lawmen—sheriffs and the Texas Rangers. I probably should have given them more time.

But I don’t spend a lot of time in good vs. evil. That’s just how I see the world. I tend to view everything in shades of gray. All these guys did some great things and some terrible things. That’s just life.

What struck me—and I’m certainly not the first to notice this—is how fluid things were. People moved back and forth between outlaw and lawman all the time. The woods are full of people like Mysterious Dave Mather, who was jailed or convicted of theft in Fort Worth and then became a deputy in Dodge City.

Almost every one of these frontier towns had a story like that. Look—small towns in the middle of nowhere with 800 people didn’t have background checks or fax machines. If a guy could twirl a gun and looked clean, that was enough to get hired.

One thing that’s really interesting in the book is how you can see the evolution of law enforcement. Early on, you’ve got these knuckleheads chasing guys like Hardin and Billy the Kid. By the 1890s, you’ve got federal marshals—guys who were incredibly professional—going after people like the Daltons. There’s real progress.

C&I: That’s always fascinated me—how law enforcement evolves based on the outlaws it’s trying to catch. I wanted to pivot briefly to modern storytelling. You mentioned Taylor Sheridan earlier. Do you see echoes of the gunfighter in today's stories?

Burrough: I didn’t really go there. One of the things I was worried about, writing about gun violence in the 19th century, was that people would try to tie it to modern politics. I couldn’t have less interest in that. So I kept my focus strictly on the 19th century. Other than a little bit about how the gunfighter emerged in popular literature and film, I stayed away from that stuff as much as I could.

C&I: And you had no shortage of great stories to tell from that era.

Burrough: No lack of stories at all. The real challenge of this book was choosing what to leave out.

Everyone knows I’m going to talk about the big four or five guys. But then it becomes a question of who else you include—and who you don’t. There are guys like Pink Higgins, Luke Short, Bill Doolin—where I’ll mention their names at a party and people just look at me like, “Never heard of him.”

But those guys have amazing stories. And that’s what I get paid to do—go out and say, “This guy has one of the coolest stories you’ve never heard.”

Wyatt Earp

C&I: The book is packed with insight, research, and incredible stories. Is there a message or takeaway you hope readers come away with?

Burrough: No. As with all my books, the first thing I want to do is entertain. I want to get you to the end.

And if, at the end, you turn around and go, “I think I learned something there too”—then I’ve done my job. But first and foremost, I want the book to be interesting and enjoyable. If readers learn something along the way, great. But I’m not going to tell them what to learn.

C&I: Last question—if you could sit down with one of these men, who would it be, and what would you ask him?

Burrough: It would be Earp. I’d want to know—he had such a reputation, well-earned, for being upright and upholding the law. But then, when his two brothers were shot—one killed—he goes rogue. He becomes a vigilante.

After years of standing in front of lynch mobs, holding them off, he crosses the line. I’d want to ask him about that.

For more about Bryan Burrough and his work, visit www.bryanburrough.com.