Martha Canary, aka Calamity Jane, wasn’t who you think she was.

Excerpted from Calamity Jane: The Woman and the Legend by James D. McLaird.

“A complete and true biography of the life of Calamity Jane would make a large book, more interesting and blood-curdling than all the fictitious stories that have been written of her,” remarked the editor of the Livingston (Montana) Enterprise in 1887, “but it would never find its way into a Sunday school library.” He added that Calamity Jane at that moment “was on a ranch down in Wyoming trying to sober up after a 30 years’ drunk.”

More than one hundred years have passed since the editor made these observations, and although numerous accounts of Martha Canary, better known as Calamity Jane, have been produced, none can be considered a “complete and true biography.” Most popular accounts make Calamity Jane a gun-toting heroine, claiming she was an associate of Wild Bill Hickok and served as a frontier mascot, stagecoach driver, and pony express rider. Conversely, most scholars debunk her purported legendary achievements and depict her as little more than a drunken prostitute. “With Calamity Jane we have the problem of the hero who performed no heroic deeds,” said biographer J. Leonard Jennewein. Since “we must not destroy our heroes, we manufacture deeds as needed.”

Favorably disposed writers did indeed invent adventurous tales about Calamity Jane. And, in order to overcome her seedy reputation, they emphasized her acts of charity and lack of hypocrisy. This produced a quandary: “Was she a frontier Florence Nightingale, Indian fighter, army scout, gold miner, pony express rider, bull-whacker, and stagecoach driver,” asked Merrit Cross in his essay for Notable American Women, “or merely a camp follower, prostitute, and alcoholic.” It also became a perplexing problem to explain Calamity Jane’s fame if she did nothing to deserve her reputation. The common response, that dime novels made her famous, begged the question. If she did nothing noteworthy, how did she come to the attention of dime novelists?

It was difficult for biographers to provide conclusive answers to these questions because few reliable sources were available. Since Martha Canary was illiterate, there was no personal correspondence, and few of her closest acquaintances bothered to describe their relationships with her. Although Martha, with the help of an amanuensis, published the Life and Adventures of Calamity Jane, By Herself, in 1896, it is brief and so filled with exaggeration that it confuses as much as it explains her activities. Even such basic facts as her name and the date and place of her birth have remained controversial.

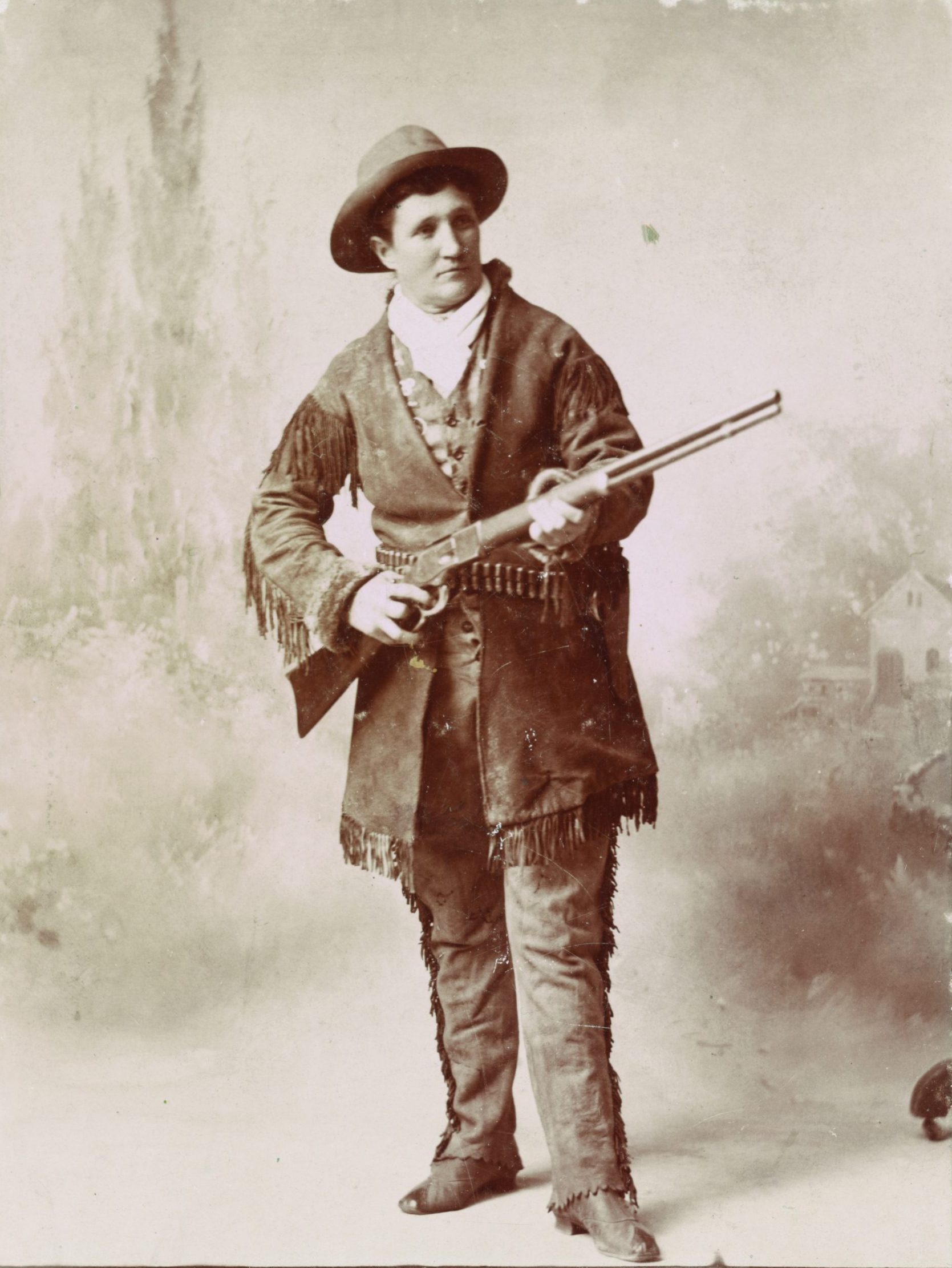

A photograph by H.R. Locke, ca. 1895: Calamity Jane, Gen. Crook’s scout, no. 2 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Retrieved from Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Item 91483145).

A photograph by H.R. Locke, ca. 1895: Calamity Jane, Gen. Crook’s scout, no. 2 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Retrieved from Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Item 91483145).

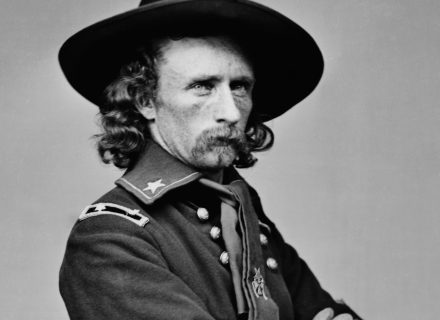

Although Martha Canary lived only 47 years, from 1856 to 1903, her life encompassed a dramatic period in the history of the American West. She experienced first-hand that era of western expansion in the late 19th century that has been the subject of endless romantic stories in popular fiction and history. Even though she never served as a scout, Martha accompanied military expeditions commanded by Colonel Richard Dodge in 1875 and General George Crook in 1876. Martha was not an intimate companion of Wild Bill Hickok, but she was with his party when it entered Deadwood during the gold rush of 1876. It is doubtful she ever helped construct railroads, but she did frequent the booming settlements established as the Union Pacific in Wyoming, the Northwestern in Dakota, and the Northern Pacific in Montana were built. There is no evidence that Martha ever panned for gold, but she joined mining rushes to the Black Hills, the Coeur d’Alenes, and possibly the Klondike. Like other well-known frontier figures, she occasionally joined shows touring eastern cities, where she related her role in the conquest of the West. By the latter period of her life, however, the West had changed and Martha’s independent and free-spirited lifestyle was out-of-place. As the legendary Calamity Jane, Martha was welcomed when she revisited earlier haunts and proudly announced that she belonged among the founders of these communities. However, positive impressions soured when Martha engaged in drunken escapades, and she often received jail sentences and requests to leave town.

In many respects, the woman who emerges from the evidence is dramatically different from the person typically portrayed in popular biographies. Illustrations depicting Calamity Jane in male attire, combined with descriptions of her scouting, bull-whacking, stage-driving, shooting, drinking, and swearing have obscured Martha’s feminine qualities. “She dressed, after her first appearance in Deadwood, as other women dressed,” wrote John. S. McClintock, who knew her during the Black Hills gold rush, “and although she was the last word in slang, obscenity, and profanity, her deportment on the streets, when sober, was no worse than that of others of her class.” Most photographs of Calamity Jane in male clothing were taken in studios for publicity purposes. Less formal pictures show her attire was a dress.

Martha also was a mother, having at least one son and one daughter, and seems to have loved her children dearly. When talking about her daughter to a reporter in 1896, Martha remarked, “She’s all I’ve got to live fer; she’s my only comfort.” Concerned about social appearances, she referred to her various male companions as “husbands.” In addition, Martha most often worked in what were then regarded as female occupations. She generally made her living as cook, waitress, laundress, dance-hall girl, and prostitute. Occasionally, she operated her own business establishments, including restaurant, laundry, saloon, and bagnio. In later life, she earned a living by exploiting her national reputation, telling her story on stage and selling her autobiography and pictures.

Martha’s downfall was alcohol. In fact, Martha’s enduring poverty derived from her acute alcoholism rather than from lack of enterprise. From the first newspaper story describing her in 1875 to the last day of her life, drunkenness was a constant refrain. Although she struggled to end her dependence upon alcohol, she failed. Sadly, her friends, despite understanding the hold it had on her, joined her in binges and supplied her with liquor.

Calamity Jane: The Woman and the Legend by James D. McLaird

Calamity Jane: The Woman and the Legend by James D. McLaird

The bleak details of Martha’s daily life stand in stark contrast to her colorful reputation. Indeed, Martha’s career offers an outstanding case study in legend-making. Minor episodes were magnified into heroic adventures and generic tales were adjust to fit Martha’s circumstances until her reputed activities bore little resemblance to reality. Despite the divergence of the Calamity Jane legend from the experience of Martha Canary, these two strands are interrelated: Being a celebrity had an impact on Martha’s attitudes and behavior, and because she was famous society responded to her differently than to other women in her circumstances.

What most separated Martha from her female companions in the West were her charisma and bold actions that gained attention from the press. Even before dime novels using her name appeared, she achieved considerable regional notoriety. But it was the appearance of her name in yellowback literature that led to her national fame. Although Martha occasionally denounced the dime novel stories about her as lies, she spun similar yarns herself, expanding her role in events she knew only indirectly.

… Sadly, after the romantic adventures are removed, her story is mostly an account of uneventful daily life interrupted by drinking binges.

Martha’s efforts to maintain family life and her employment in menial jobs relegated to women have been overshadowed by her image as a gun-toting, swearing, hard-drinking frontierswoman. Not surprisingly, histories of women in the West emphasizing monotonous daily chores and the difficulty of managing family, home, and work, find Calamity Jane an unacceptable model. In fact, historian Glenda Riley says that writers who romanticize the lives of “famous women who acted more like men than women” suffer from the “Calamity Jane syndrome.” Evidence showing Martha to be a caring, if incompetent, parent working in commonplace jobs will require that Calamity’s image as “bad woman” be modified.

… Martha, like Buffalo Bill, is an anomaly in the history of the West. Her importance rests not on the similarity of her life to that of other frontier women, but on the manner in which her life was reshaped to fit a mythic structure glorifying “the winning of the West.”

From Calamity Jane: The Woman and the Legend, the University of Oklahoma Press. Available from OU Press, Amazon, and everywhere books are sold. Used by permission.

From our November/December 2024 issue.

HEADER IMAGE: Calamity Jane at “Wild Bill” Hickok’s gravesite in Deadwood, Dakota Territory, c. 1890s