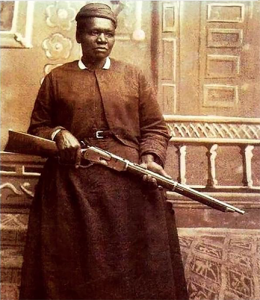

Come to 1880s Montana and meet the first African American woman Star Route mail carrier in the United States. When you discover more about the real woman, you'll understand this impassioned argument for rejecting the frontier misnomer "Stagecoach Mary."

The problem with the nickname "Stagecoach Mary" is that the Black woman to whom the tag is attached, Mary Fields, never drove a stagecoach. The innocent-sounding misnomer is not so innocent.

Scant and fictional are the supposed details about her life before she traveled west and into history.

Mary was born into slavery in the spring of 1832 in Hickman County, Tennessee, where she lived for approximately 33 years. Post-emancipation, she began a new life that eventually led her to Ohio. We take up her story in her 53rd year, when the Montana chapter of Mary Fields' life began as she boarded a train in Toledo on a dark winter's night in 1885.

Her departure was unplanned — a telegram had alerted her that last rites were being arranged for her friend Mary Amadeus, who was fighting the clutches of pneumonia. Three days later, Fields disembarked from the Great Northern in Helena, Montana, facing two more days of travel. Wagons drawn by two-horse teams, and finally, a single-harnessed sleigh delivered her across deep layers of snowpack marking entry into a wilderness known as The Birdtail, named after the monolithic rock that towered 1,000 feet above prairie hills and valleys, its peak geologically etched into the appearance of a feather headdress or a bird's tail.

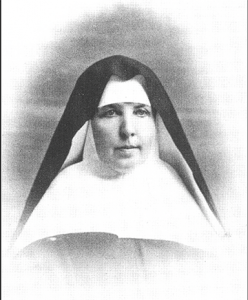

Miles of pristine splendor waned as her destination came into view. Entering a small lone cabin, dilapidated and isolated, Mary saw Native American girls cowering in a corner, hardened patches of ice clinging to walls, Ursuline nuns coaxing her into the dark interior, eyes glancing to and from Mary Amadeus placed in the center, on the floor, supine, lids closed, and most distressing, sounds of rattled breath convulsing, and lapsing into silence. The severity stifled customary greetings; whispers slide across the chill.

Mary attended to the charismatic leader while the four women wearing black busied themselves with religious and educational duties. Fields understood the purpose of the Ursuline Roman Catholic Order, founded to rescue, house, and educate young girls at risk to provide them with a chance, a new life; she had spent years working as groundskeeper at the Toledo convent school and knew the depth of her friend's commitment. Amadeus would not leave these girls; she had come in response to a tragic crisis. Reports of violence toward Indians help captive in Army forts included claims of murder, sexual abuse, and government agents who withheld food allotments until starving families conceded to reprehensible demands and handed over beloved daughters, who were then forced into prostitution.

The pioneer nuns had run out of food and money. Their sole source of heat, an iron stove, would not alleviate frostbit limbs without fuel. Following school lessons taught during the day, the undernourished sisters and their Indigenous pupils slept on the frozen earth floor, and Mary Fields would, too. She had decided to stay.

Fields not only possessed the ability to keep everyone alive short term; later, her survival, ranching, and equestrian skills would surpass expectations. Enduring hardship was nothing new to her; she had labored as a slave since her birth, until after the United States Congress ratified the 13th Amendment in December 1865. In addition to caring for Mary Amadeus, Fields quickly resolved the immediate life-threatening issues by providing food, (wild game rendered by trap and rifle), stacks of dry wood, and repairs to the hand-hewn cabin.

After Mother Amadeus' recovery weeks later, the Indian school increased in size and continued to do so during the next decade. The cabin was eventually replaced by a three-story stone building. Mission projects expanded to include livestock, crops, and religious services for nearby homesteaders. The Ursuline settlement, located within harsh polar conditions (climatic, political, social, and ethnic) managed to succeed primarily due to the dedicated efforts of Mary Amadeus and Mary Fields. Amadeus, grateful for Fields' indispensable contributions, promised Mary that her home would continue to be there with them for the duration of her life.

An Ursuline annal entry states, "Mary Fields did everything we couldn't."

"Everything we couldn't" included the following, without the job title credits:

- Hennery construction and manager: Mary's hennery housed over 400 chickens and ducks, supplying alternate sources of meat and eggs, essential for baking bread and other staples.

- Freighter: Mary routinely drove the mission horses with whatever vehicle was available — buckboard, buggy, or makeshift farm wagon — across country so rough it required remarkable knowledge and grit to avoid or recover from any number of catastrophes. She hauled lumber, stone, tools, and hardware, medicinals, dry goods, and occasional passengers — a job few pioneers could accomplish. She and her horses sustained injuries from wolf attacks and wagon crashes and found themselves, more than once, alone in prairie darkness, forging through snow and blizzard winds up to 70 miles an hour in subzero tempatures.

- Agriculture consultant and gardener: Mary evaluated locations to grow a variety of crops for mission use. She also planted and maintained large herb and vegetables gardens to feed the entire population of approximately 200 people at the height of operations.

- Ranching stockwoman: She contributed to the care of livestock: horses, cattle, and sheep.

- Mentor: A confidante to Indian and Metis girls, Mary was commended in records for her love of young people and her popularity with them. As the only woman who was neither white nor a nun, intimately familiar with the loss of personal freedom and culture of origin, she offered invaluable support.

- Musician: Mary read music and played the guitar, banjo, and harmonica.

- Caregiver: Mary nursed Indian, Metis, and white girls during epidemics and quarantines of scarlet fever, tuberculosis, and diphtheria.

- Laundress: She instructed female pupils in laundry techniques and procedures and supervised their work to produce washed and pressed clothing for themselves, the Ursulines, and the neighboring Jesuit fathers in charge of male boarding school students.

- Protector: A respected sharpshooter, Mary provided expert rifle and handgun skills.

Ursuline Mission quarters, school, and bell tower, with Mary Fields (far right) sitting on farm hayer, circa 1887

Ursuline Mission quarters, school, and bell tower, with Mary Fields (far right) sitting on farm hayer, circa 1887

Adding to Fields' attributes, Father Lindesmith, an Army chaplain and frequent mission visitor, noted in journal entries that, without fail, it pleased him to be in the company of Mary's happy disposition; he also mentioned her good cooking.

In July 1894, the first Catholic bishop of Montana, the Rev. John Baptist Brondel, used his position to circumvent Mother Amadeus' authority over the Ursuline community when he sent Mary Fields a letter, stating that he had received complaints of her bad behavior and ordered her, the mission's steadfast champion for nearly a decade, to leave immediately.

He mailed a note to Amadeus simultaneously, instructing her and the sisters to cease all contact with the "laundress." Fields traveled over 100 miles to confront him. She insisted that he present proof of the false claims; he refused to change his edict. Ursuline diaries relayed the nuns' sadness and stated, "He [the bishop] has heard aspersions of the woman's [Mary Fields'] character. ... We should like to have an account of the interview between the Bishop and Black Mary." Decades later, fictitious stories about Mary Fields alleged that she was fired from the mission due to a shootout, but archive evidence does not support the cumulative myth.

Mary Fields improved every community she chose to join, including Cascade, the Montana town nearest to the mission, where she relocated and quickly reinvented her vocation. She established an eatery, a one-person operation (not a grand saloon as depicted in The Harder They Fall). Mary closed the doors approximately 10 months later; she had continually fed customers unable to pay.

Soon after, in 1895, she obtained the position of Star Route mail carrier, driver for a 34-mile route from Cascade to the Ursuline mission and back. "Expressmen" who drove these arduous routes were well-respected for their abilities. U.S. mail delivery, protected under federal jurisdiction, made the bishop's edict unenforceable — this must have pleased Mary and Ursulines. Many worked this route for two four-year terms, driving horse and wagon, never a stagecoach, across the rocky Birdtail terrain, providing reliable service to growing numbers of residents.

Fields' contributions to the region did not guarantee gratitude or respect. In 1897, cowboy artist Charles M. Russell sketched a pen and ink drawing titled A Quiet Day in Cascade, which depicted Mary knocked down by a hog, eggs spilled from her backset onto the dusty thoroughfare. According to oral accounts, Fields, upset by the insulting image, declared that no such incident had ever occurred.

According to some Cascade whites, the town's population had already been forced to adjust to unexpected and apparently unwanted neighbors two years prior to Mary's residency, when in 1892, 200 Native American youth arrived at Fort Shaw Government Industrial School, a decommissioned, remodeled Army fort 20 miles north. The assimilation trainees were put to work farming hundreds of prime local acres appropriated by the government. In a diplomatic gesture, the school's superintendent attempted to reduce conflicts by transporting Indian student musicians to Cascade on a regular basis, entertaining locals with orchestrations of popular band tunes.

Everyone knew that change was inevitable. Broad divisions of moral and legislative codes had contributed to the development of factions, increasing the possibility that violence could interrupt plans for security, causing ordinary folk to consider extreme measures. The change in mood was reflected by Montana's own nicknames created by the White population; the Territory, originally called "Land of Shining Mountains," had been upgraded to the "Treasure State," a global destination for everyone ready to strike it rich. A local newspaper headline confronted, "Execution of a Chicken Thief at Fort Shaw — No Trial or Hearing Whatever Allowed the Accused — Are Such Acts to be Allowed in a Civilized Country?"

Mary Fields, invariably addressed as "Black Mary" or "N***** Mary," had been a fly in the ointment to those who insisted that her relocation to Cascade had only been allowed due to her longtime association with the Ursulines and her ability to freight heavy wagonloads of essential supplies during early settlement days.

Mary Fields on buggy, early Ursuline Mission, circa 1887

Mary Fields on buggy, early Ursuline Mission, circa 1887

At some point during Mary's career as the Star Route mail carrier, frustrated Cascade residents concocted a new name for Mary, channeling discriminatory opinions into a customized parody to deflect and humiliate; to change her identity from the strong freighter who forged through treacherous elements and delivered what was needed to nuns, homesteaders, and traders — the grit that made things happen — into a trivial anecdote.

They chose a name connected with, but different from, her fundamental regional role: mail delivery. The "Stagecoach" twisted conjured Wild West sentimentality, changing "the essential express freighter" into "our local dutiful driver." The effect, whether or not the denigrating implications were understood or purposeful, was to objectify the only Black resident by fictionalizing her profession and mocking her identity each time the nickname "Stagecoach Mary" was spoken.

A cunning caricature, the new moniker was utilized like a public relations trademark, drawing attention to the otherwise-unremarkable town that flanked the Missouri River — an easy transgression considering the odds of reprisal. Eager to join the legend limelight, white Cascade residents chimed in, contributing their own ideas to the fictional free-for-all. Catchphrase jingles generally included "Stagecoach Mary is 6 feet tall and weighs 200 pounds. She smokes cigars and her face is as black as burner prairie. A crack shot with rifles and revolvers, she is our mascot."

Fields was 71 when she retired from the Star Route in 1903 and established a laundry business, which she operated from her Cascade home. She also offered childcare services and spent the proceeds purchasing hard candies and fresh fruit for her charges, resulting in lasting friendships with youngsters and their parents. Some locals resented her full-time presence, preferring the mail-route arrangement that had required her absence six days a week. Mary did not leave. Armed with self-respect and willpower, she stood her ground amid powerful conflicted forces of ostracism and acceptance.

There were neighbors — men, women, and children —who, thought they may not have understood her, responded in kind to Mary's generosity, knowledge, and resolve. Parents insisted that Cascade School close its doors for a half-day every March 15th so that the Mary Fields' birthday-party tradition, initiated by Ursuline sisters, would continue. Burt Stickney, owner of the Cascade Hotel and its restaurant, House of the Well Fed, expressed personal gratitude to the illustrious pioneer by gifting her with free meals for the remainder of her lifetime.

In 1910, Mary agreed to the town baseball team's request and became the Cascade Cubs Mascot. It was no small decision, as mascots often withstood demeaning treatment during this time period. In addition to oiling the bats and washing and ironing team uniforms, Mary crafted her homegrown flowers into boutonnieres for each Cub player and cheered them on from the sidelines. At the end of each game, she presented a victory bouquet to the winning teams.

Montana towns had become eligible to petition for "city status" after the territory's admittance to the Union in 1889. Cascade's application, approved in January 1911, warranted an immediate city election. The new mayor and his aldermen passed several ordinances straight away, including an ordinance that reduced women's rights — specifically, Mary Fields' rights. The new law, not published in the newspaper along with the others, denied females entry into saloons. Since Cascade's infancy, Mary had socialized in the town's watering holes on fact-finding missions to obtain relevant news of strangers, outlaws, or local conflicts — a clever precautionary measure, essential for protection while freighting and delivering mail on the open road alone, which she did from 1885 to 1903, long before Cascade supported a newspaper. Accounts from locals contend that though the unpublished saloon ordinance applied to all females, it had been legislated solely to terminate Mary Fields' access.

The ordinance violated Mary's freedom and threw her into isolation. Opportunities for news and camaraderie with the broad range of working men she had associated with — laborers, contractors, cowboys, and business owners — had been eliminated. Social interactions had been reduced to brief exchanges with merchants, restaurant patrons, and parents of the child she babysat. Still in effect a year later, the cruel enactment may have contributed to the former mail carrier's decision to take another risk: Mary Fields marched into the post office and registered to vote on February 17. 1912. Though her house burned down within a month, good friends and neighbors build and tenacious old-timer a new one.

In 1913, D.W. Monroe, a longtime acquaintance of Fields', won the mayor's seat in Cascade's second city election. He saw to it that Mary was exempted from the "women are forbidden in saloons" ordinance. This gave Mary 18 months to enjoy rekindled freedom of movement and time to socialize freely before she died from natural causes on Decemeber 5, 1914, at the age of 82.

Mary Fields had lived in Montana for 29 years. Her conviction toward the region region reflects her arrival's intention — to save her friend's life. Though accurate numbers of people Mary rescued from death are undocumented, estimates from mission populations alone total more than a few. Mary was also an experienced survivalist and problem solver — valuable resources to brave wilderness travel and confront the unexpected. Her circle of interest grew from voluntary efforts, driving horses and wagons through fierce conditions to deliver essentials to those living miles apart with little contact from the world — a chivalrous service she undertook regardless of the recipients' race or ethnicity.

Against all odds, the reliable Montana pioneer cultivated a place to call home within the region's thorny heart.

Mary Fields, mascot for the Cascade Clubs baseball team, circa 1911

Mary Fields, mascot for the Cascade Clubs baseball team, circa 1911

Mary's funeral was well-attended, though local obituaries memorialized her by addressing her as "Stagecoach Mary," "Cascade Cubs Mascot," and their "Town Mascot" — nicknames that continued to objectify the extraordinary frontier woman. Bouquets of flowers, likely a fond gesture given Mary's history of flower propagation, abounded, yet the small tin cross that marked Mary's grave offered no identification. It remained blank.

As decades passed, awareness of Mary Fields and her dedicated achievements faded. Remembrance publications occasionally reiterated the usual legend, often in conjunction with regional Ursuline history. In 1959, Ebony magazine published an article about "Stagecoach Mary" as relayed by actor Gary Cooper, a Montana native. While briefly generating broader awareness of Mary Fields, the account also contributed to increased levels of misinformation. By the 21st century, it was nearly impossible to discern fact from fiction. None of the Mary Fields or "Stagecoach Mary" legends included Mary Fields' voter registration, a public record.

The original "Stagecoach Mary" moniker and legend were created by people of Mary's generation. It was the next generation — the children with whom Mary shared genuine, less-biased relationships — who relayed their personal memories of the woman, the friend, the babysitter they knew and loved. Their words created the oral history that lived on the into the hearts of their descendants, enabling the legend to survive long enough to be rediscovered and inspire a new chapter — the careful excavation and examination of complex frontier interactions that, in this case, revealed substantial regional history and viable additions to Montana and United States history.

Mayor Monroe's son, Earl Monroe, the last living person to have known Mary Fields, recalled in an interview shortly before he passed, "Mary was gentle and love. She held me in her lap and sang to me with a deep voice. She was a second mother to all us kids."

Years after Mary's death, it was Earl who returned to right a communal wrong. Why did Cascade residents include their Black neighbor in the town's "hallowed ground" yet eliminate evidence of their decision and Mary's identity by leaving her grave marker blank? Does this reflect strong opposing sentiments of the populous? Certainly it illustrates how easily vital history can be lost.

In honor of Mary Fields' significance, both to his family and the Birdtail region, Monroe placed a large granite boulder at the head of her grave in Cascade's Hillside Cemetery. The ancient stone, inscribed "Mary Fields 1832 – 1914," attests to the woman's actual name and dates of birth and death, marking proof of Mary's final resting place and testimony to her importance.

At long last in 2006, the correct status of Mary Fields' mail carrier route was actualized. Newly discovered documents established Mary's authentication as the first African American woman Star Route mail carrier in the United States. Former claims that Mary Fields was "the first African American woman hired by the U.S. Postal Service" or "the second woman and the first black woman to have a mail route in America" were put to rest.

Mary Fields' voter registration record was also discovered in 2006, followed by formal regional acknowledgment that Mary Fields was the first African American to register for the vote in Cascade, Montana.

To correct a few of the "Stagecoach Mary" legend claims: Mary was not 6 feet tall, was not violent, and did not participate in shootouts. She was strong, tough, smoked cigars, and wore men's coats and hats to stay warm. Mary boldly exercised her legal rights and worked independently on her "own account" devising methods to obtain more freedom whenever possible. Her steadfast strength and positivity generated trust and goodwill. Her life epitomizes the strength of the human spirit.

By rejecting the derogatory and reductive nickname "Stagecoach Mary," along with the false assertions within the legends, we reduce the perpetuation of racism and preserve the truth of Mary's life, bestowing our nation with an American hero's genuine identity, a historical legacy worthy of appreciation, contemplation, and celebration.

Mary Fields manifested a fearless belief in herself and in humanity. Let us follow her lead. We can begin by addressing this inspired human being by her given name.

Mary Fields in Cascade, Montana, circa 1908

Mary Fields in Cascade, Montana, circa 1908

Mianae Metcalf McConnell is the author Deliverance Mary Fields, First African American Woman Star Route Mail Carrier in the United States: A Montana History, a 2018 Oprah Top 10 book. McConnell's more than 10 years of research established the historical authentication that enabled USPS archivists to verify Mary Fields as the first African American woman Star Route mail carrier in the U.S. and the discovery and verification of Mary Fields' 1912 voter registration. Visit miantaemetcalfmcconnell.com.

This article appeared in our May/June 2023 issue, which can be found on newsstands now or through our C&I Shop.