Almost 70 years ago, the marshal of Conniption rode into the nation’s newspapers courtesy of Montana cartoonist Stan Lynde.

This is a tale of two cowboys — both good guys. The first is Rick O’Shay, the boyish, amiable marshal of a town called Conniption. From 1958 to 1981, the comic strip exploits of Rick, gunslinger Hipshot Percussion, and gambler Deuces Wild appeared daily in the nation’s newspapers.

The second was Stan Lynde — Montana-born and raised in a world of cowboys, ranchers, and Native Americans from the Crow Indian Reservation. He grew up with a love of the West and Charlie Russell and a talent for drawing, which he put to good use when he created Rick and his friends.

At a time when newspapers are struggling for survival, it’s hard to imagine the devotion newspaper comic strips once held for millions of Americans. From Little Orphan Annie to Flash Gordon to Dick Tracy, their stories captivated generations. Western fans were not forgotten on what used to be called the funny pages, with strips featuring characters like Red Ryder, Vesta West, and singing cowboy Gene Autry. But there was something about Rick O’Shay that seemed to resonate more deeply with fans.

“Stan felt the longevity of Rick O’Shay was due to those rural values he acquired in childhood,” said Stan’s wife, Lynda, several years after he passed away in 2013. “He paid special attention to authentic detail in his work; he knew those who followed the strip would know if he wasn’t accurate.”

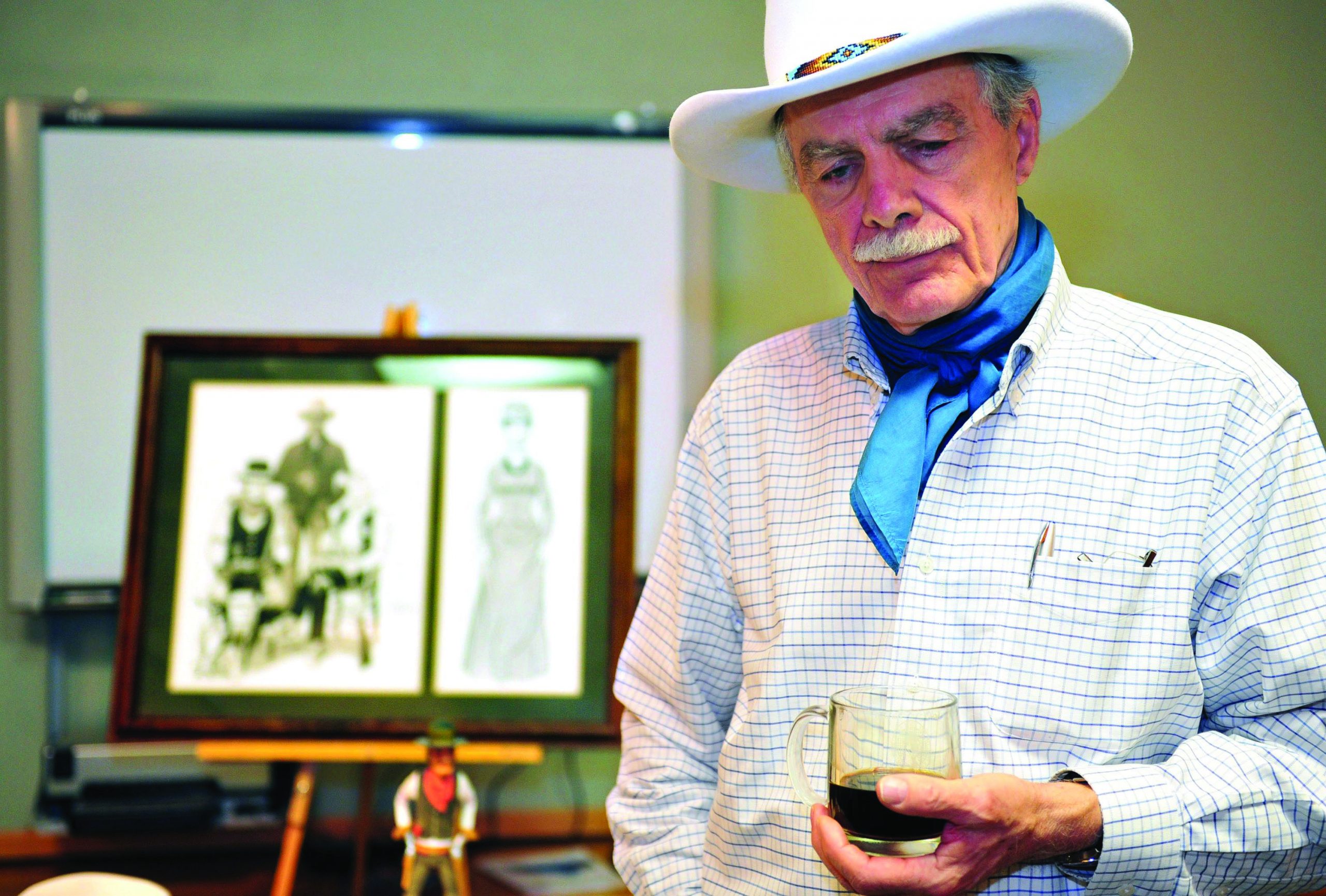

Inspired by the cowboys of his Montana youth, Stan Lynde created the long-running comic strips Rick O’Shay and Latigo; pictured here in November 2012, he died at 81 in August 2013.

Inspired by the cowboys of his Montana youth, Stan Lynde created the long-running comic strips Rick O’Shay and Latigo; pictured here in November 2012, he died at 81 in August 2013.

The year Rick O’Shay debuted there were more than 25 westerns on television. This was not a coincidence. “While a few of these series were very good, many were not really westerns at all,” Lynde wrote in his book Rick O’Shay, Hipshot, and Me. “My goal from the start with Rick was to produce a feature which would satirize the fictional western from the standpoint of the authentic West, the West in which I had grown up.”

Thus, the early strips featured stories like “Tom Foolery,” in which a historical Western figure returns after 50 years and is outraged to find his life has become the subject of a television series. He rides to Los Angeles to confront the producers. “Kyute Movie” has members of the local tribe filming their own movie about Native American life to protest Hollywood stereotypes.

Character names were among the strip’s signature delights. Among the most memorable (if sometimes unseemly by today’s standards) were saloonkeeper Gaye Abandon (who became Rick’s wife), town doctor Basil Metabolism, Rick’s deputy Manuel Labor, and an orphaned baby dubbed Quyat Burp.

The charismatic mustachioed outlaw Hipshot Percussion became more popular with readers than Rick himself. Newspapers threatened to cancel the strip after a 1966 story left the gunfighter critically wounded. Montana governor Tim Babcock expressed his concern by offering Hipshot a full pardon for “all misdeeds committed in Montana ... and amnesty for all other misdeeds.”

By that time, the strip was already evolving from its satirical roots. Cold War intrigue reached Conniption in 1966’s “Plenty Tooth,” and “Bearcat” raised awareness about saving the environment just one year after the first Earth Day in 1970.

The high point of the strip’s mature era may have been “Trackdown,” a grim revenge tale published in 1974 – 75 in which Hipshot is targeted by an old enemy. Stan Lynde’s richly detailed drawings were by then enhanced by Denney NeVille, who helped produce Lynde’s pencils in the strip’s final six years.

“Most of his inkers at that time used a pen, but because of my art training I was more intrigued by doing it with a brush, which gave the strip a more fluid edge, and Stan really liked that,” NeVille recalled. “It was a lot of work. It probably took Stan eight to 12 hours to draw a Sunday page, and it took me four to five hours to ink it. But he had a drive for quality work, and that was one thing I admired about him. I would show up at 7 a.m. to start my day and find that he had been there all night. He had a capacity to work like no one else.”

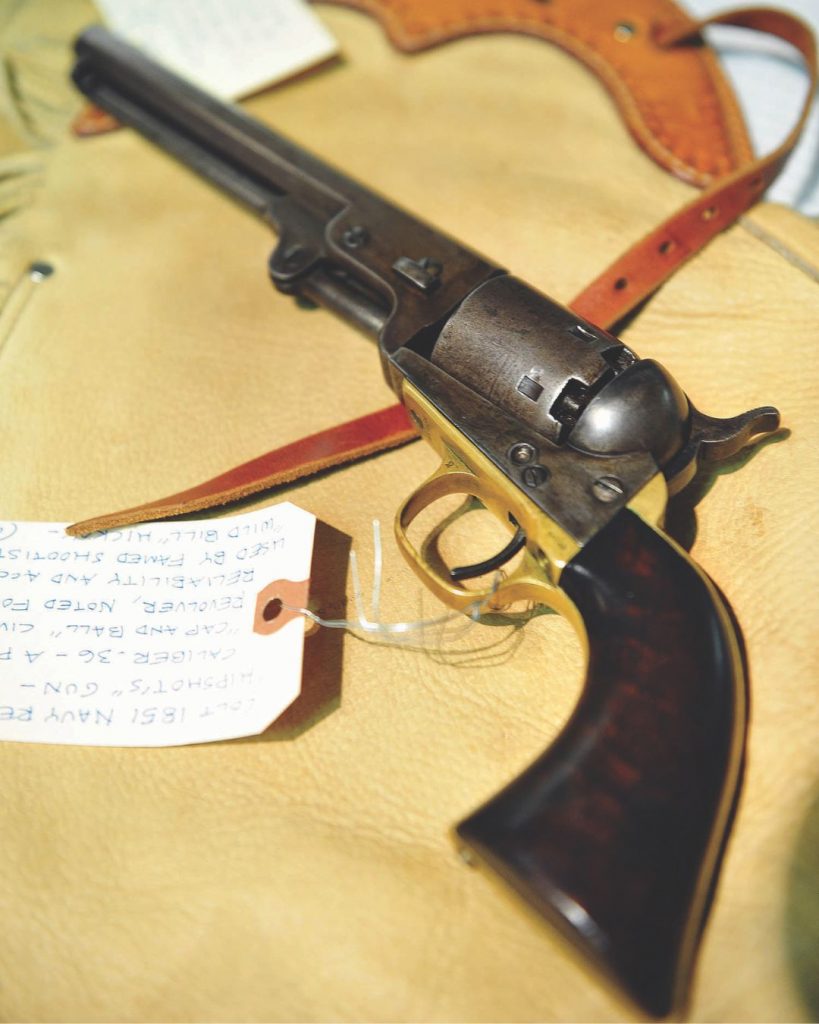

Left: A cup emblazoned with the character Hipshot was among Lynde memorabilia donated to the Montana Historical Society. Right: A Colt 1851 Navy revolver used by Wild Bill Hickok was comic-strip character Hipshot’s gun. Lynde wore these chaps (shown under the revolver)— which have his registered brand, RIK, on the hip—during the Great Montana Centennial Cattle Drive in 1989.

Sadly, Lynde’s connection to his beloved characters ended before the comic strip did, when he gave notice to his newspaper syndicate following a revised agreement he thought was unfair. The company figured it could keep the strip going with a new writer and artist. Bad move.

“They did not consider [Stan’s] knowledge base of the characters or the authenticity generated from his Western background or his unique storytelling voice,” Lynda remembered. “I grew up on newspaper cartoons, but I personally never went searching for a cartoonist as his fans did with him. Many said they saved the clippings every day, so even after it was no longer in the newspaper they could share it with the next generation. He was given a great deal of credit from them for the wisdom he imparted through Rick O’Shay. When he left there was a huge outcry from fans, and the strip subsequently could not continue under a new team.”

Almost 50 years after the last strip, fans still write to the Stan Lynde website to request prints of memorable O’Shay Sunday strips that were rerun over the years, such as Rick’s “Happy Birthday, Boss” message as he looks skyward at Christmas, and Hipshot’s New Year’s “Moderation” Sundays.

“I don’t kid myself that my readers have been so loyal because I’m some kind of genius. ... I simply share the same attitudes and values that people who have grown up with the land and with nature hold, and have held before me,” Lynde wrote in his book Rick O’Shay, Hipshot, and Me. “The difference is only that I had the platform, and that I have been fortunate enough to be considered a kind of spokesman. It is an honor, and one I value for which I am profoundly grateful.”

When those fans ask where Rick O’Shay and Hipshot are today, Lynda tells them what Stan used to: “They are where they’ve always been, somewhere in the mountains near Conniption.”

Stan Lynde’s spurs, also worn in the Great Montana Cattle Drive, were among items Lynde donated to the Montana Historical Society before his anticipated relocation to Ecuador with his wife, Lynda.

Stan Lynde’s spurs, also worn in the Great Montana Cattle Drive, were among items Lynde donated to the Montana Historical Society before his anticipated relocation to Ecuador with his wife, Lynda.

Stan Lynde Post Script

On August 6, 2013, just two months before he would have turned 82, Myron Stanford Lynde died of cancer in Helena, Montana. He and his wife, Lynda, had barely embarked on their new lives in Ecuador, where they had planned to live out their retirement. To lighten their relocation, they had donated much of their materials and memorabilia to the Montana Historical Society. Among the artifacts: ornate spurs Lynde wore in the Great Montana Cattle Drive (a gift from Les Kellum in 1989); a Colt 1851 Navy revolver (“Hipshot’s” gun) used by famed shootist Wild Bill Hickok; chaps with Lynde’s registered brand, RIK, on the hip, made by Carol Kellum in Gardiner, and first worn by Lynde during the Great Montana Centennial Cattle Drive in 1989.

In a farewell talk to the Montana Historical Society in December 2012, Lynde had called the move the first chapter of a brand-new book. The couple had packed their belongings in four suitcases, two backpacks, and a camera bag to settle in South America, thinking they would go back to Montana for a few months every fall. But when Lynde got sick with what turned out to be squamous cell lung cancer, they returned to his home state permanently.

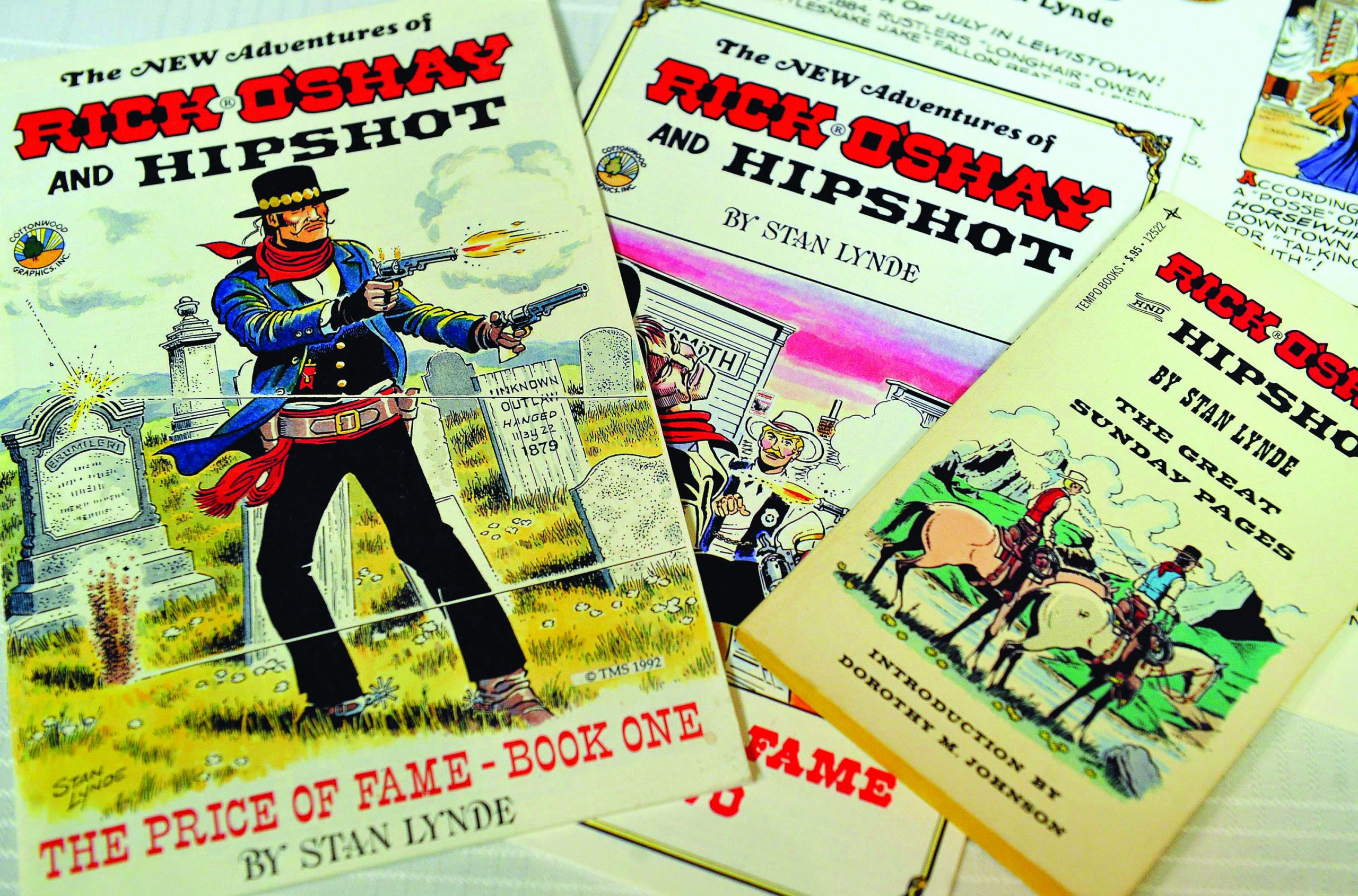

Rick O’Shay, Hipshot, and Me: A Memoir by Stan Lynde includes 10 complete stories from the daily comic strip and an introduction by Charlton Heston.

Rick O’Shay, Hipshot, and Me: A Memoir by Stan Lynde includes 10 complete stories from the daily comic strip and an introduction by Charlton Heston.

“I feel very blessed,” he said in an interview with Helena’s daily newspaper, Independent Record. “I’ve been able to do the work I love for an appreciative audience. I love this state and people of this state. If my tombstone said something about Montana, I’d be really happy. I’ve never met any state with people who have such character.”

Lynde was buried in his birthplace of Billings. Instead of a quote, his tombstone bears an image that conveys something about the man and Montana. A cowboy on horseback in the mountains—(somewhere near his fictional Conniption?) his hat in hand, his face upturned—appears to be giving thanks.

From our August/September 2024 issue.

PHOTOGRAPHY: Eliza Wiley/Independent Record