Close friends, historians, and artists shed light on the life of Earl Biss, the Crow artist who helped spearhead the contemporary Indigenous art movement.

My favorite artist is Earl Biss. No. 2: Vincent van Gogh. When I say Earl Biss is my favorite artist, I’m not grading on a scale. I don’t mean my favorite painter or Native American artist; I mean my favorite artist.

I’ve felt a spiritual connection to Biss’ paintings, and him, from the moment I first saw his work. It’s unlike anything before or since. That first time was at The James Museum of Western and Wildlife Art in St. Petersburg, Florida, and I remember the moment as distinctly as I recall seeing my wife for the first time.

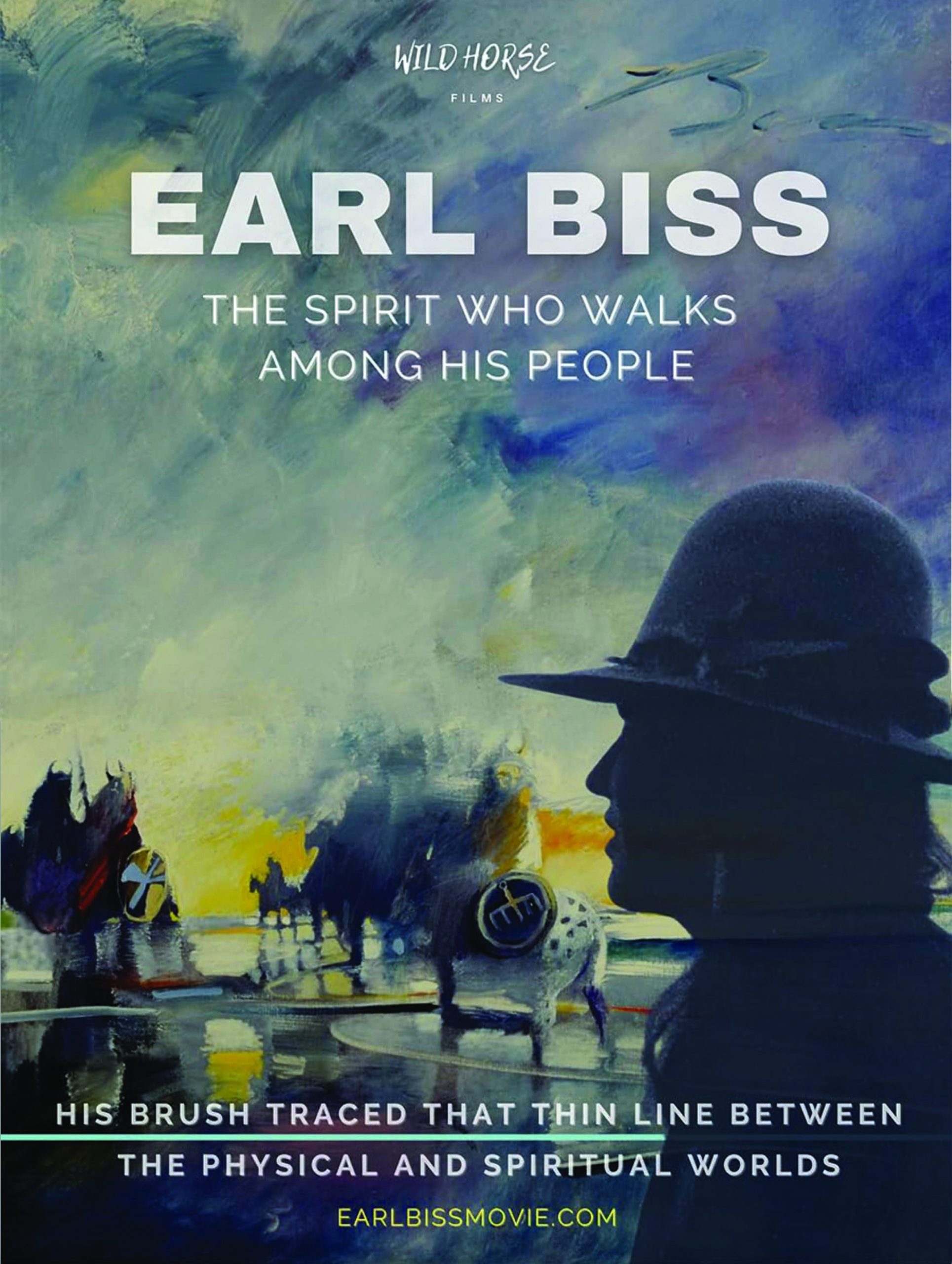

Lisa Gerstner’s documentary Earl Biss: The Spirit Who Walks Among His People, released in late April 2023, shares Biss’ genius and spirit and Gerstner’s personal background with Biss.

Gerstner first met Biss at a party in Aspen, Colorado, in 1994 through a mutual friend, who thought Gerstner should write Biss’ biography. Gerstner was not a professional writer and, with only a few published articles under her belt, had never attempted a project so ambitious.

In her book Experiences with Earl Biss: The Spirit Who Walks Among His People, Gerstner recalls the artist sizing her up at the party. Without fanfare, she asked him plainly, “Am I your biographer?”

“Yes. I can just tell,” he answered, never having talked to or spent any time with Gerstner.

Biss as a toddler with grandmother Margaret Spotted Horse Stewart, Crow Agency, Montana (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Loretta Stewart Thomas/Dana Ivers).

Biss as a toddler with grandmother Margaret Spotted Horse Stewart, Crow Agency, Montana (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Loretta Stewart Thomas/Dana Ivers).

Gerstner worked directly with Biss on and off for the next year and a half before losing track of him. Four years later, by happenstance, she saw an ad in a Denver newspaper for one of his upcoming shows. At the exhibit, Gerstner asked him if he wanted to finish the book. He did.

It was the last time the two would see each other in the flesh. Biss died a month later at 51 years old.

“It was a leap of faith,” Gerstner said, referring to writing Biss’ biography. She didn’t realize that 20 years would pass before the project she took on resulted in a finished product. The book was published in 2018, and the documentary was completed in 2021.

An astonishing trove of video footage and photographs from throughout Biss’ life highlights the production. Biss was born in 1947 and raised on the Apsáalooke Reservation in Montana. It’s not surprising video and pictures exist from when Biss was an art world superstar in highfalutin Aspen in the 1980s. But how so many pictures and videos were taken, let alone remain, of the artist’s childhood — including early childhood photos with his grandmother, who raised him, when he couldn’t have been more than 3 years old — is miraculous. This was 60-some years before everyone held a camera and video recorder in their pocket. These items couldn’t have been cheap or commonplace on the reservation.

Not long before his death, Biss candidly revealed his thoughts on art, life, spirituality, and indigeneity in 1997 during an extensive on-camera, sit-down interview with Dana Ivers, which the film incorporates considerably.

Riders of the Foothills With a Witching Moon, oil on canvas (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Galerie Zuger Santa Fe).

Riders of the Foothills With a Witching Moon, oil on canvas (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Galerie Zuger Santa Fe).

The years — and hard living — are visible on Biss in this footage. He’s no longer the lithe, energetic artist he was earlier in the decade — vibrant, full of vim and vigor, painting in darkened basements with both hands at the same time, removed from this physical world yet plugged in to another spiritual world.

His Apsáalooke name was Iláaxe Baahéeleen Díilish, the Spirit Who Walks Among His People.

“I’m holding the brush and someone else is doing the painting and the thinking,” Biss says in the documentary.

Footage of him painting recalls Michael Jordan dunking from the free throw line or Jimi Hendrix playing guitar. Staggering genius. You can’t believe your eyes.

Earl Biss At IAIA

Beyond a biography of Biss, the film adeptly documents the so-called Miracle Generation of initial enrollees at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was Biss, Kevin Red Star, Doug Hyde, T.C. Cannon, Linda Lomahaftewa, and their classmates — under the direction of Lloyd Kiva New, Fritz Scholder, Allan Houser, and Charles Loloma — who invented contemporary Native American art.

In the same way that Monet, Renoir, Degas, and their colleagues invented impressionism and forever altered the course of modern art, Biss and his contemporaries similarly invented a genre, one which has yet to achieve its zenith, gaining greater recognition every day in the hands of their successors, including Wendy Red Star, Biss’ niece.

Land of the Free, Home of the Brave, 1991, oil on canvas, 60 x 84 inches, private collection (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Galerie Zuger Santa Fe).

Land of the Free, Home of the Brave, 1991, oil on canvas, 60 x 84 inches, private collection (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Galerie Zuger Santa Fe).

She’s Kevin Red Star’s niece as well, and if the film has a co-star to Biss and his artwork, it’s Biss’ longtime friend, second cousin, IAIA classmate, and fellow Apsáalooke Kevin Red Star, who refers to Biss as “little brother.”

Numerous intimate photographs from these early days at IAIA are shown in the movie. An amazing sequence of Biss dressed in regalia clowning around with Cannon, who’s wearing street clothes, stands out.

Remarkable items of Biss ephemera from the voluminous collection of the IAIA Native Artist Files are seen. News clippings, gallery show opening announcements, a college recommendation letter for Biss written by Scholder. IAIA, at this time, was a high school.

Earl Biss Stories

They’re true. All of them. The stories you hear about Biss. My personal favorite comes from Bill Rey, owner of Claggett/Rey Gallery in Edwards, Colorado. Rey’s been working the art scene in the Colorado mountain resort towns since Biss’ career was at its apex. He remembers a scheduled show opening for Biss on a Friday night. An hour before the show, there was no artwork.

Minutes before opening, Biss and some friends — he always had a lot of friends — pull up in a dump truck with a load of giant wet canvasses. Masterpieces produced in a frenzied trance of activity that could have lasted multiple days uninterrupted by sleep. Biss tended to paint that way at the time.

They all sold.

Earl Biss painting in San Francisco, 1969 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Dana Ivers).

Earl Biss painting in San Francisco, 1969 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Dana Ivers).

He was selling paintings for more than $50,000 in the mid-’80s when that was real money, even in Aspen and Vail.

Not that he kept any of that money.

Another of my favorite Biss stories is how he was advanced something like $20,000 the night of a gallery opening by the owner. But come Monday, he was back asking for the rest of his cut because he’d spent it all.

Biss lived for the moment. Cadillacs. Champagne. Drugs. He lived the monied, celebrity ’80s lifestyle as outrageously as any actor or rock star. In Aspen, he debauched with fellow wild man and gonzo journalism creator Hunter S. Thompson.

T.C. Cannon, Fritz Scholder, and Earl Biss, 1975 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Dana Ivers).

T.C. Cannon, Fritz Scholder, and Earl Biss, 1975 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Dana Ivers).

The film makes no attempt to hide this, nor should it. Biss was not perfect by any means.

He was a womanizer. He was married about 10 times — a precise accounting of wives no more possible than a precise accounting of the number of oil paintings he produced. He drank hard. He partied hard. Hard drugs. Jail time. IRS trouble.

His mischievous smile a window into his soul.

Through Gerstner’s interviews with Biss’ ex-wives, family, friends, attorney, the former sheriff of Pitkin County where Aspen is located, colleagues, collectors, and adopted son Dante (a successful artist himself), Biss is revealed as playful, generous, the life of the party, the Spirit Who Walks Among His People.

Title unknown (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy Galerie Zuger Santa Fe).

Title unknown (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy Galerie Zuger Santa Fe).

Postscript

Biss suffered a massive stroke at age 51 on October 18, 1998, in his Santa Fe studio. For most people, that seems young. Biss squeezed at least 100 years of experiences into his 51. His most recent 51, anyway. Biss firmly believed he had lived past — and would likely live future — lives.

He loved, he saw the world, he helped invent an art form, he made a fortune, he spent a fortune, he helped uphold his culture, and he found a calling at which he possessed a unique brilliance he is still esteemed for today.

Gerstner magnificently reveals this in her film.

Iláaxe Baahéeleen Díilish.

Earl Biss at San Francisco Art Institute, 1968 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Marlene Rogoff, courtesy of Dana Ivers).

Earl Biss at San Francisco Art Institute, 1968 (PHOTOGRAPHY: Marlene Rogoff, courtesy of Dana Ivers).

The Restless Spirit Moves

The art of Earl Biss defies categorization. So did the man and his “medicine.”

When fully engaged, Earl Biss moved like an athlete, dynamic and with certainty, flinging paint at the canvas, rhythmic, plugged in to a power source we cannot see, using brooms and mops and rags to “move paint around,” as he described it. Biss was not modest when assessing his ability to do so. Nor should he have been.

His biographer, Lisa Gerstner, took video that captures much more than a virtuoso with paint, a genius; viewers are shown the supernatural. Biss is seen painting with both hands simultaneously, using multiple brushes in concert, pouring water on the canvas, using his hands—not his fingers—conjuring images from only he knows where to create his breathtaking expressionist scenes.

What was it like being in the room as Biss spent his “medicine” on the canvas?

Title unknown (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy Galerie Zuger Santa Fe).

Title unknown (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy Galerie Zuger Santa Fe).

“I would describe it as Earl becoming more himself,” Gerstner explains. “Not like you hear about people channeling something other, but he became more who he was as a soul, beyond the mind and emotions, and there was this connection to his culture and this other realm where these other Crows—whether they were still alive or passed on and were visiting—you could feel hundreds of Crows in the room when he was painting and he was very open about that. He said, ‘Yeah, they’re coming through the paint. I didn’t do that; they did that.’ You could feel the presence of all of these souls of the Crow culture. The beautiful, powerful way of being, he captured that in paint, and he could tune into that and the other realms and bring it into the physical realm.”

In Gerstner’s documentary, Kevin Red Star, a fellow Crow and friend of Biss, recalls an extraordinary story of Biss flying to the Crow Reservation in Montana simply to observe one sunset and the following sunrise to make sure he had his colors right.

Big Fat Chief, oil on canvas, 38 x 36 inches (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy Galerie Zuger Santa Fe).

Big Fat Chief, oil on canvas, 38 x 36 inches (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy Galerie Zuger Santa Fe).

No camera. No sketch pad. He only needed to look.

“There was something about the environment and the people. You notice a lot of his work has these giant skies with masterful colors. I’ve never seen anyone work with color like him before. He just knew everything there was to know about color and everything there was to know about the way oil paint feels under your hands,” says Gerstner, who’s also a painter with a fine arts degree. “He’d say things like, ‘Between the atoms and molecules there’s a lot of space, so there has to be something there. The spirit is between those atoms and it’s alive, and that’s what I’m painting.’”

Movie poster for Earl Biss: The Spirit Who Walks Among His People, directed and produced by Lisa Gerstner (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy Galerie Zuger Santa Fe).

Movie poster for Earl Biss: The Spirit Who Walks Among His People, directed and produced by Lisa Gerstner (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy Galerie Zuger Santa Fe).

The book and documentary: Find both as well as a list of the streaming platforms where you can watch the film (earlbissmovie.com).

The exhibition: An Earl Biss art show will be on view August 16, 17, 18 during Indian Market at Galerie Züger Santa Fe; Biss biographer Lisa Gerstner will be in attendance (galeriezuger.com).

The biopic: A feature film about Biss—working title Cry of the Thunderbird, to be shot in New Mexico with a large Native cast—is in development (cryofthethunderbird.com).

Reprinted from Essential West, with the permission of Mark Sublette/Medicine Man Gallery (medicinemangallery.com).

From our August/September 2024 issue.