Eliciting emotion through art, this Native painter remained an optimist fueled by hope.

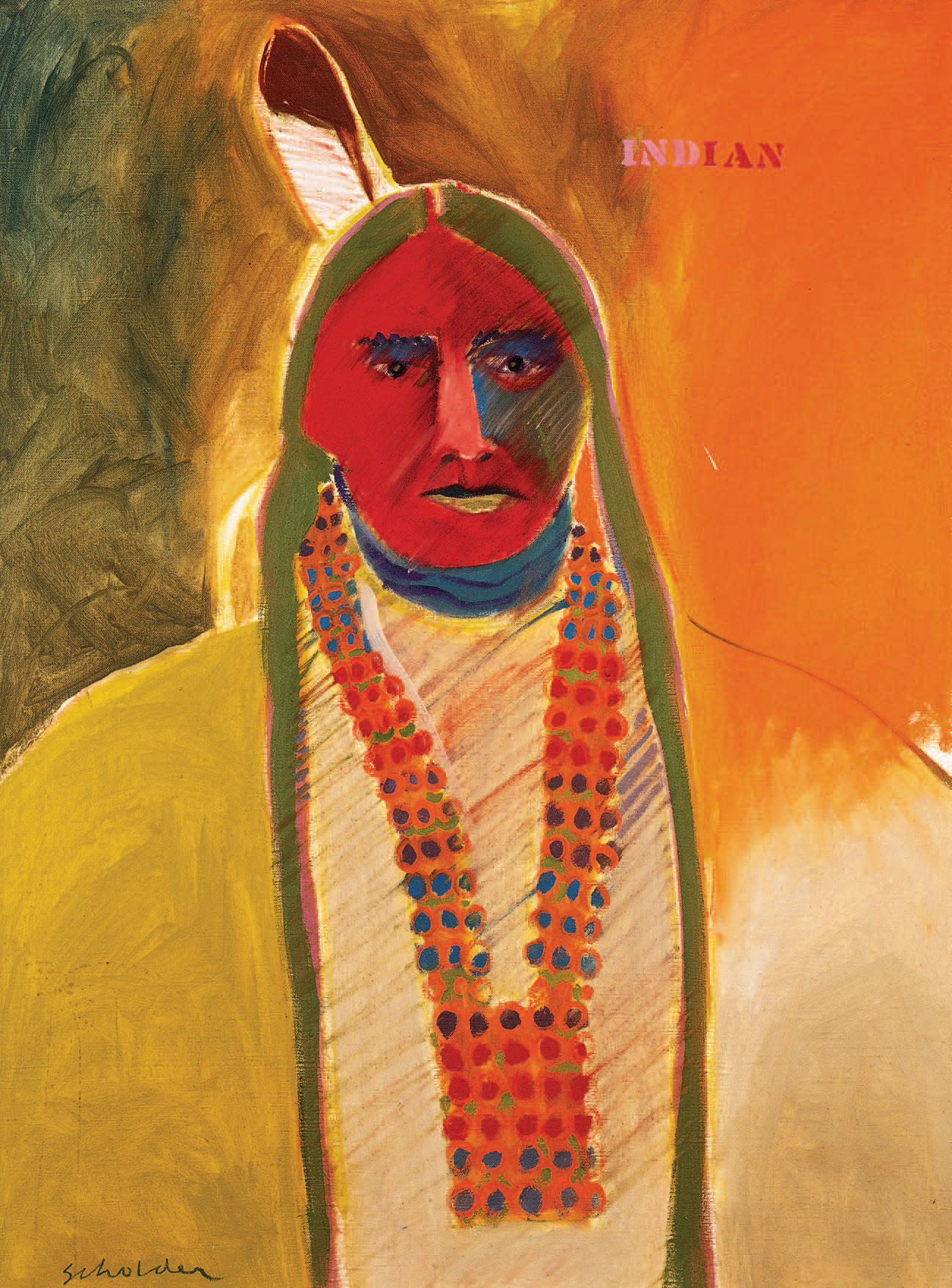

Fritz Scholder once vowed never to paint Indians. An enrolled member of the Luiseño Mission Tribe who didn’t embrace his Indian identity until he was an adult, he disavowed the label “American Indian artist.” Then again, he said he was proud of being an American Indian and became famous for painting Indians. But don’t focus on those much-trodden seeming contradictions of Scholder’s life and art — focus instead on his paintings.

That’s the urging of John Lukavic, associate curator of Native arts at the Denver Art Museum and curator of Super Indian: Fritz Scholder, 1967 – 1980. The traveling show, which opens at DAM in October, mounts more than 40 rarely seen monumental paintings and lithographs by the renowned 20th-century artist, including early Indian series, pop art, psychological portraiture, stereotypes and representation, and “dark, mysterious” subjects.

“This is the first exhibition to really feature Scholder as a figurative artist and colorist, which I think he wanted to be his legacy,” Lukavic says. “Many of these paintings are 68-by-80 inches. If you take that one step closer, the subject matter is obscured and you’re confronted with his use and pairing of color. He said one color is boring — the buzz of energy is when you put one color with two or three. He was trying to elicit emotion through the use of paint. People were shocked when they saw the subject matter, and he polarized the art world. People either love or hate his work, but one way or another they are impacted. It’s really about the paint and the emotion generated through his use of paint. We’re talking about Fritz all these years later because of the emotion he captured in his paintings.”

Born in 1937 in Breckenridge, Minnesota, Scholder spent an artistic youth in the Midwest. By the time he was 20, he had relocated to Sacramento, California, where he trained under influential painters Wayne Thiebaud and Gregory Kondos. He would also be influenced by Irish-born British figurative painter Francis Bacon, whose bold, emotionally charged, raw imagery earned both acclaim and revilement, as would Scholder’s. But where Bacon was a bleak chronicler of the human condition, Scholder maintained that even at his darkest and most morbid — Dog and Dead Warrior, Massacre in America, Dying Indian in Nebraska — he was an optimist fueled by hope.

Like Bacon, Scholder painted in series. “When Fritz started to paint the Indian series,” Lukavic says, “it was not subject first, then technique. It was technique first. He always said the most important things were, one, color; two, composition; and, three, subject matter.” Still, subject matter was hardly relegated as the artist pushed against romantic past notions of Indians in painting and determined to portray them as “real, not red.” Hence, he might memorialize a buffalo dancer taking a break from performing to enjoy a strawberry ice cream cone from a concession stand. “That very famous Super Indian No. 2 and others, like Indian and Contemporary Chair, Indian with Strawberry Soda Pop, and Indian in Car, all put the Native American in a context that breaks the stereotype of the 1880s and brings a contemporary feel of what it is to be Native in contemporary society into American consciousness.”

The years the exhibition focuses on — 1967 to 1980 — see Scholder in the heyday of his career: “This is when he created some of his best work.” A very active painter who got through his works quickly, Scholder, Lukavic says, has been unfairly labeled a regional artist because he worked so much in the Southwest. “He’s no more a regional artist than Georgia O’Keeffe. He certainly enjoyed a lot of fame in his life, but I don’t think it was anywhere near what he deserved. He was such an important part of the world art scene at the time. I’m hoping this exhibition will help solidify his place in American art history and world art history and achieve name recognition for Scholder that is commensurate with his art.”

Super Indian: Fritz Scholder, 1967 – 1980 is on view at the Denver Art Museum October 4, 2015 – January 17, 2016; it then travels to the Phoenix Art Museum February 26, 2016 – June 5, 2016, and the Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art in Overland Park, Kansas, June 23, 2016 – September 18, 2016.

From the October 2015 issue.

HEADER IMAGE: American Portrait with Flag (Photography: Courtesy Denver Art Museum)