Find out exactly what happened when bank-robbing murderers Bonnie and Clyde met their fates in a hail of bullets on May 23, 90 years ago.

On this day 90 years ago, Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow were brought to a just and ignominious end on a dusty road in northwestern Louisiana, much as they had long predicted for themselves. The foundational couple of the notorious Barrow Gang — better known to later generations as Bonnie and Clyde — both lived and died in a hail of bullets. The ruthless and unapologetic duo had sworn never to surrender, a promise for which they took 13 lives in their effort to keep.

In early 1932, the gang of alternating career criminals — centered around Clyde — embarked on a two-year multistate robbery, kidnapping, and murder spree. Contrary to popular myth, their victims were mainly average citizens and small mom-and-pop shops and gas stations, not banks. The handful of bank robberies they did attempt were mostly failures, which led to discontent and frequent attrition within the gang.

Always determined to evade responsibility for their litany of brutal crimes, the gang rebuffed any effort to give them their day in court with a barrage of automatic gunfire. They brazenly ran roadblocks and blasted their way out of at least a dozen arrest attempts, murdering many of those who stood in their way. Bonnie often bragged that she and Clyde would “go down together.”

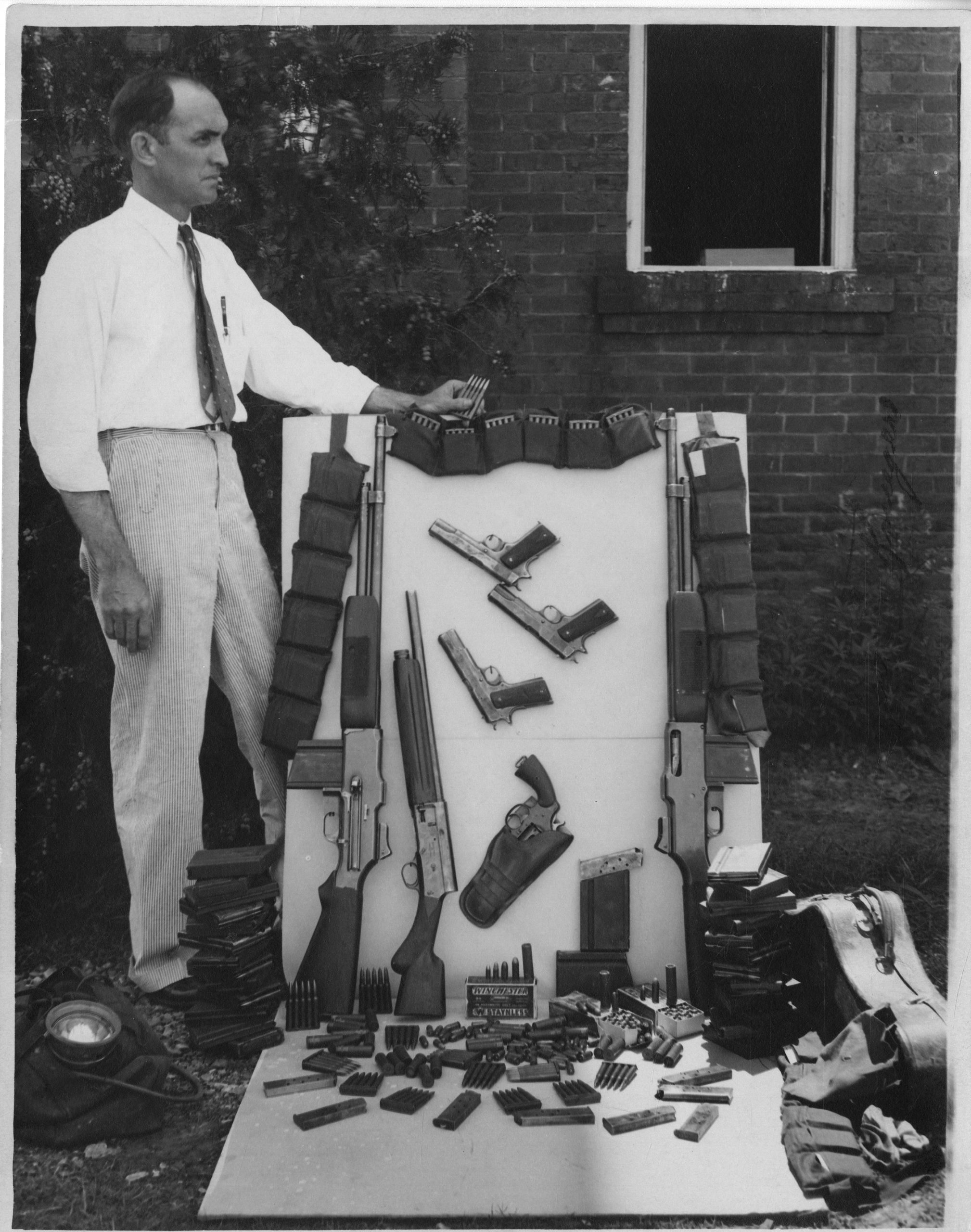

Photo of part of the weapons cache found in the Bonnie & Clyde “Death Car" (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of the Texas Rangers Hall of Fame and Museum).

Photo of part of the weapons cache found in the Bonnie & Clyde “Death Car" (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of the Texas Rangers Hall of Fame and Museum).

Federal agents, plus multiple state and local authorities — over a thousand officers in all — spent two years in a fruitless and often deadly attempt to bring the gang to justice. In the end, the team of resolute lawmen who finally tracked down Bonnie and Clyde was led by none other than Texas’ most famous lawman, Francis Augustus “Frank” Hamer — former senior captain (“chief”) of the Texas Rangers. Hamer was officially brought into the chase by Lee Simmons, general manager of the Texas prison system, after Bonnie and Clyde’s daring and deadly Eastham Prison break.

Over the course of his pursuit of the homicidal duo, Hamer ended up carrying three separate law enforcement commissions, including one from a Dallas County district court, another from the Texas prison system, and the third from the Texas Highway Patrol. After Bonnie and Clyde murdered two Texas highway patrolmen near Grapevine, Hamer asked his neighbor and fellow former Texas Ranger Maney Gault to join him. Gault had been working as a Travis County deputy since leaving the Rangers — along with Hamer and several others, in protest of the notoriously corrupt “Ma” Ferguson’s reelection — but accepted a commission from the highway patrol in order to join Hamer as a representative of that agency. Together with a team from Dallas County and Bienville Parish, Louisiana, they formed the posse of law enforcement officers who finally “put [Bonnie and Clyde] on the spot.”

Despite Hamer’s much higher public profile, every officer on that team made specific and unique contributions to the successful hunt for Bonnie and Clyde. Sheriff Henderson Jordan of Bienville Parish, together with his deputy Prentiss Oakley, provided both the legal authority for the team to operate in Louisiana as well as contacts within the local community that were essential to smoking the clandestine couple out of hiding. Dallas deputies Bob Alcorn and Ted Hinton were both knowledgeable about the deadly duo’s accomplices and methods, and could identify them both on sight. Together, the team devised a classic dragnet to ensnare the elusive and deadly fugitives from justice.

After midnight on Wednesday, May 23, 1934, the posse assembled in the woods along a remote road in northwestern Louisiana to await their savage quarry.

At approximately 9:15 a.m., the depraved duo unwittingly drove into that carefully laid trap, drawing their murderous reign to a violent conclusion. The mostly veteran officers who lay in wait for them were well-aware that the Barrow Gang’s modus operandi was to blast their way out of any arrest attempt, often expending in excess of 1,000 rounds of ammunition and taking as many lives as necessary in the process. Despite modern mythology to the contrary, a warning/opportunity to surrender was given on the day of their demise — the lawmen involved all independently reported that fact. However, both Bonnie and Clyde and the officers all knew they would never heed it. Sure enough, their reaction to the warning was to grab for their firearms. Such would be the final choice of their short and violent lives.

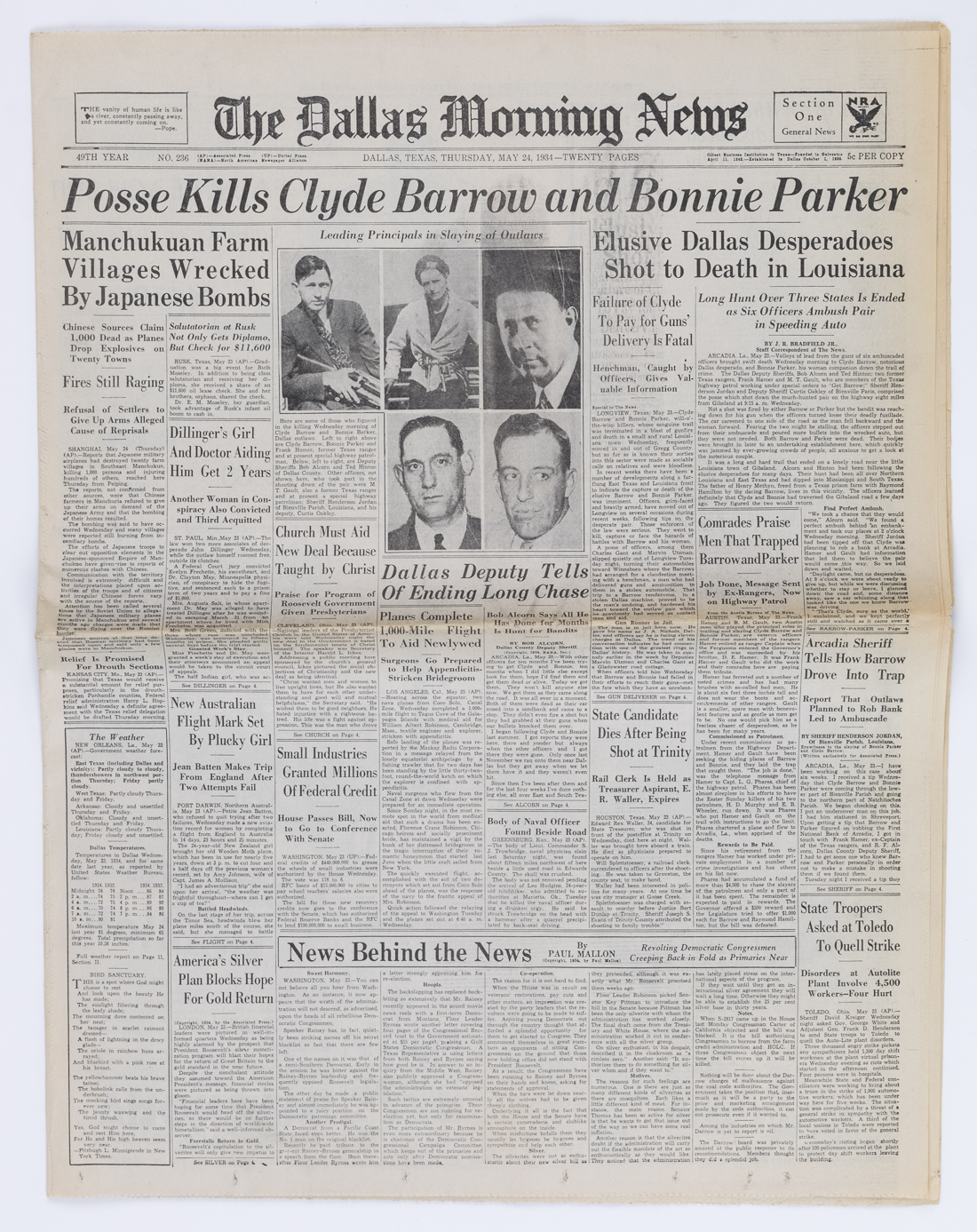

Dallas Morning News headline article dated May 24, 1934, the day after Bonnie & Clyde’s murderous crime spree was finally ended (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of the Texas Rangers Hall of Fame and Museum).

Dallas Morning News headline article dated May 24, 1934, the day after Bonnie & Clyde’s murderous crime spree was finally ended (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of the Texas Rangers Hall of Fame and Museum).

Clyde grasped the Browning automatic rifle (BAR) that he always kept at his side while driving, and Bonnie raised a Colt 1911 semiautomatic pistol. Having anticipated as much, the ever-vigilant lawmen unleashed a volley of gunfire into the stolen 1934 Ford V-8, Model 40B Fordor Deluxe Sedan.

Clyde was struck in the head, although it did not explode as reported in some exaggerated accounts. Bonnie’s pistol hand was shredded by the first salvo, and her blood-soaked weapon fell onto the seat beside her. She also had a .38 revolver strapped inside of her hip and a custom-altered shotgun — used to murder the two highway patrolmen at Grapevine — nearby, as well. Meanwhile, Clyde’s right hand was still gripping the stock of his BAR. Contrary to another popular myth, Bonnie did not have a sandwich in her hand, only the gun. If there were sandwiches in the car, they were not anywhere to be seen in deputy Hinton’s film of the car’s contents, which was shot immediately after the ambush.

The total number of bullets fired at the pair is a matter of some debate. Each trigger-pull for a five-round shotgun loaded with buckshot would result in a minimum of 16 projectile impacts in the car and the fugitives. Therefore, five trigger-pulls from each resulted in a minimum of 80 holes — 120 if there were, in fact, three shotguns employed. That’s roughly half to almost three-quarters of the highest estimate asserted, which is 167. Therefore, if only two of the posse-men were firing shotguns, then the other four expended, at most, a total of 20 rounds each, which would equal the emptying of a single magazine by each shooter. However, the most reliable sources indicate that only Ted Hinton was carrying a fully automatic BAR with a 20-round magazine. The other rifles involved, whether two or three, at the most, were Remington Model 8 semiautomatics with fixed, five-round magazines. In any event, the 167 “bullet holes” are, arguably, not as “excessive” as many have made them out to be.

In contrast, the Bonnie and Clyde “Death Car,” as it has come to be called, was loaded for bear with at least 17 fully loaded firearms, including three BARs, two sawed-off shotguns, 10 Colt automatic pistols, and two revolvers. They also had a total of approximately 3,000 rounds of ammunition. Most of that arsenal was hidden underneath a robe in the back seat, except for the four or five weapons immediately on Bonnie’s and Clyde’s persons or beside them in the front seat.

If there had been any question in the minds of those intrepid lawmen as to the threat that the bloodthirsty twosome posed to them on that fateful morning, it was quickly answered. Bonnie and Clyde’s vow to “go down together” was no idle expression of bravado, and the posse had been wise to take them at their word.

Having endured two years of the gang’s wanton and indiscriminate violence, both the American public and all the lawmen who had been pursuing them could finally breathe a sigh of relief. Finally, that inexplicably brutal episode in American history was brought to an unavoidable and just conclusion.

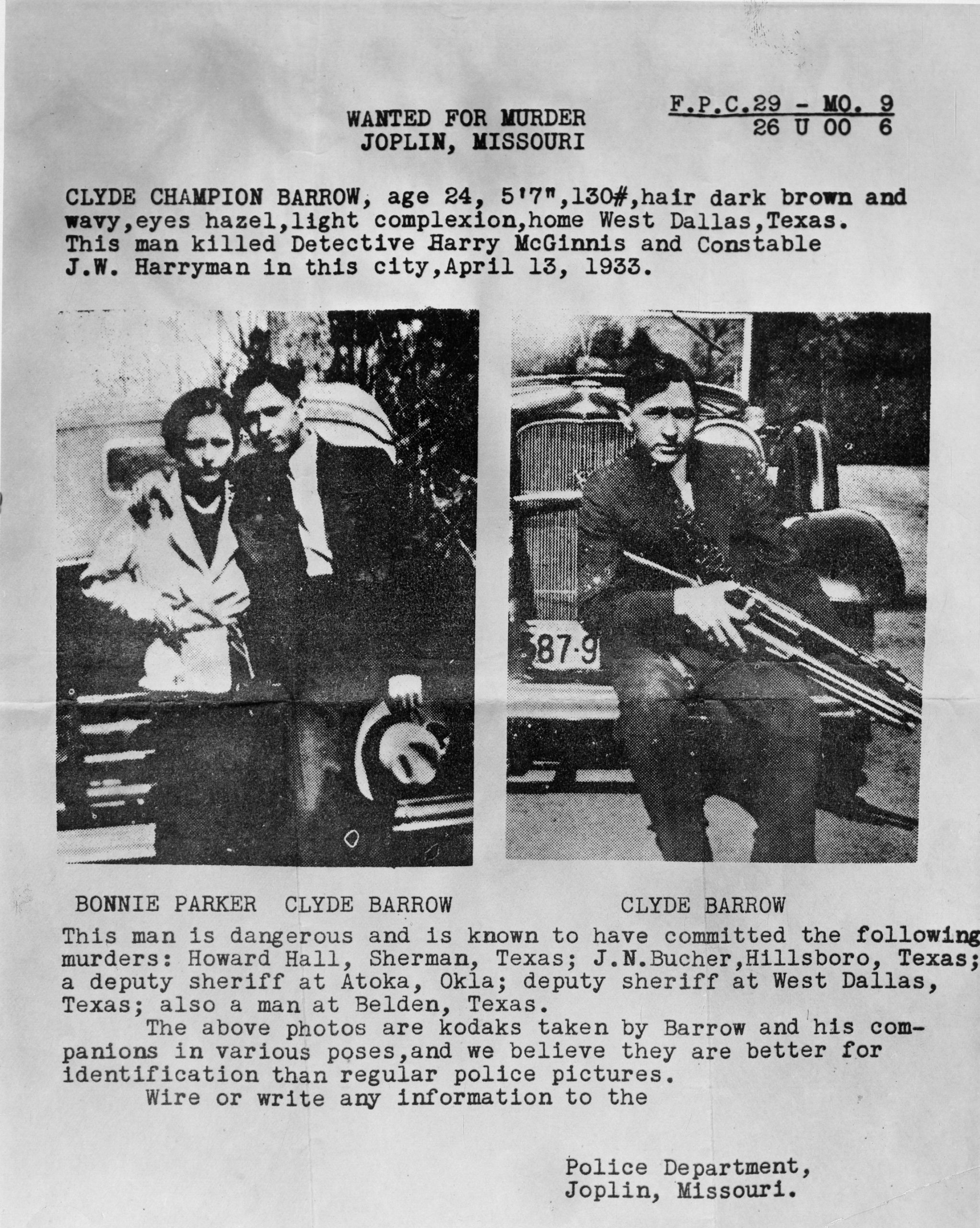

Bonnie Parker jokingly points her rifle at Clyde Barrow in a rare photo of the duo (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Dr. Jody Edward Ginn).

Bonnie Parker jokingly points her rifle at Clyde Barrow in a rare photo of the duo (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Dr. Jody Edward Ginn).

As Bonnie and Clyde had dealt, so had they received.

Notwithstanding the early criminal careers of each member of the Barrow Gang, they are most remembered for those final two years, during which they engaged in a cross-country odyssey of unbridled violence. While Bonnie and Clyde were no longer of this world, the families of their victims would never truly recover from the losses inflicted by such barbarous outlaws.

From April 1932 through May 1934, the Barrow Gang inflicted many atrocities upon the American public. They stole dozens of cars, often through the threat or use of violence. At a time when even the most affluent Americans were struggling to survive financially, cars often represented not only one of their most costly investments, but they were also essential to their ability to earn a living. Many, if not most, of those vehicles were irreparably damaged by the time they were abandoned for the next stolen vehicle, a total and considerable financial loss for the victims. And, it was those cars — along with the arsenal of weapons stored inside them — that enabled the gang to avoid accountability for their crimes for so long.

The gang committed countless armed robberies, most of which were — contrary to popular myths — committed against small mom-and-pop businesses just trying to stay afloat during the Great Depression, as well as against average, ordinary, working-class individuals. The gang frequently beat — and even murdered — robbery victims who dared to defend their property. They also robbed a train station, a meat-packing plant, and two National Guard armories — the latter to replenish their stock of automatic weapons lost during some of a dozen violent escapes, including the one they blasted their way out of in Joplin, Missouri. Those robberies were how they supported themselves financially, as they chose a life of crime instead of honest employment. While the vast majority of Americans remained hardworking, law-abiding citizens throughout the Great Depression, the Barrow Gang chose to take what was not theirs and kill anyone who dared challenge them.

The Division of Investigation for the US Department of Justice (now, F.B.I.) was able to join the hunt for Bonnie & Clyde based on their having violated federal laws by crossing state lines in stolen vehicles. Both were also indicted in state courts for multiple murders (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of F.B.I. - Famous Cases and Criminals: Bonnie & Clyde file).

The Division of Investigation for the US Department of Justice (now, F.B.I.) was able to join the hunt for Bonnie & Clyde based on their having violated federal laws by crossing state lines in stolen vehicles. Both were also indicted in state courts for multiple murders (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of F.B.I. - Famous Cases and Criminals: Bonnie & Clyde file).

The Barrow Gang also took up kidnapping as a means of escape, mostly of law enforcement officers but also of civilians. They kidnapped and beat Dillard Darby and Sophia Stone, after the unwitting pair attempted to follow junior gang member W.D. Jones, who had stolen Darby’s car from in front of their boardinghouse, while they were watching. The killer couple, who had been living in their car for weeks, did their worst: Clyde pistol-whipped Darby, and Bonnie subjected Stone to the same treatment, all while taunting them with death threats.

Over the course of their two-year crime spree, the Barrow Gang also kidnapped up to seven law enforcement officers. When they released a severely wounded Percy Boyd, chief of police in Commerce, Oklahoma — whom they had kidnapped after Bonnie gunned down Constable Cal Campbell — Bonnie admonished Boyd to tell the press that the picture of her smoking a cigar was staged in jest. She offered no denials regarding the numerous accusations of her participation in armed robbery, shootouts, and murder — other than Grapevine, which she, Clyde, and Henry Methvin all denied on behalf of each other (and all later recanted) in that moment. Clyde also ordered Boyd to warn all of law enforcement that they would continue to murder any officers who attempted to take them in to custody.

Those invested in the myths perpetuated by the almost completely fictionalized 1967 film — among other irreputable sources — often complain that the lawmen should have provided Bonnie and Clyde with more of an opportunity to surrender. They argue that the way they were killed was unfair and suggest that the killer couple might well have complied and were entitled to have had their day in court. Of course, such protestations belie the fact that the gang blasted their way out of at least a dozen such opportunities and repeatedly promised to continue.

In fact, it was precisely in response to such overtures that the gang committed the lion’s share of their murders — which totaled at least 13. Bonnie and Clyde knew better than anyone that they were guilty and had no intention of returning to prison or taking their leave via the electric chair. Instead, they chose what today is commonly referred to as “suicide by cop.” The posse merely chose the timing for them.

Photograph of the team that took down Bonnie & Clyde, each identified in handwriting. The senior officers seated front, left to right: Deputy Bob Alcorn, Dallas County S.O.; Sheriff Henderson Jordan, Bienville Parish, La.; and Frank Hamer, Texas Prisons/Texas Highway Patrol; Standing in back, left to right: Deputy Ted Hinton, Dallas S.O.; Deputy Prentiss Oakley, Bienville S.O.; and Maney Gault, Texas Highway patrol (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of the Texas Rangers Hall of Fame and Museum).

Photograph of the team that took down Bonnie & Clyde, each identified in handwriting. The senior officers seated front, left to right: Deputy Bob Alcorn, Dallas County S.O.; Sheriff Henderson Jordan, Bienville Parish, La.; and Frank Hamer, Texas Prisons/Texas Highway Patrol; Standing in back, left to right: Deputy Ted Hinton, Dallas S.O.; Deputy Prentiss Oakley, Bienville S.O.; and Maney Gault, Texas Highway patrol (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of the Texas Rangers Hall of Fame and Museum).

Those robbed, kidnapped, and murdered by the gang were far from their only victims. They also left 10 widows, a fiancée, and at least nine orphans and their families to fend for themselves, having stolen their husbands, fathers, sons, and brothers from them — sole breadwinners, in that place and time — amidst the most desperate economic times in American history. Those families all suffered multigenerational trauma from that loss. They were also subjected to the worst sort of insult-to-injury when, barely more than a generation later, the gang was fictionalized, romanticized, and immortalized as counterculture antiheroes in a major motion picture viewed by millions worldwide. It would be another half-century before a comparably platformed feature film, Netflix’s The Highwaymen, would — at long last — set the record straight.

Lee Simmons — who as general manager of the Texas prison system first put Hamer on the trail of Bonnie and Clyde — bluntly yet thoughtfully concluded: “Clyde and Bonnie were put on the spot. I make no apology for that. I never have, and I never will. The criminals’ mothers [both convicted coconspirators] said that their children had been shot from ambush without ever having a chance. That was true. But none of the victims of Clyde and Bonnie ever had a chance for his life. … As they had sowed, so also had they reaped.”

Dr. Jody Edward Ginn is a former law enforcement investigator and U.S. Army veteran who works as the director of development for the Texas Rangers Hall of Fame and Museum, in Waco, Texas. Ginn has been a historical consultant to museums, educational institutions, and filmmakers, and is a former adjunct professor of history at Austin Community College. Ginn has authored publications on various Texas history topics, including “Texas Rangers in Myth and Memory,” in Texan Identities (UNT Press, 2016). Ginn’s latest book is East Texas Troubles: The Allred Rangers’ Cleanup of San Augustine (OU Press, 2019).