Quashing myths and exploring the real history of the infamous outlaw duo Bonnie and Clyde — what The Highwaymen got right.

Almost 90 years ago, Bonnie and Clyde were finally brought to justice on a remote dirt road in northwestern Louisiana. Shortly thereafter, the Barrow and Parker families found themselves charged in federal court with having aided and abetted interstate fugitive murderers. It was then that numerous myths about the gang were first created by the defendants, in an attempt to avoid responsibility for helping their notorious relatives. Most notably and insidiously, members of the Parker family began insisting that Bonnie was simply a sort of “good girl led astray” by Clyde, and in particular insisting that she never shot or killed anyone. Nevertheless, and despite such protestations of innocence, multiple juries found them all guilty as charged and sentenced even the killer-couple’s mothers, Cumie Barrow and Emma Parker, to federal prison terms.

As the jurors clearly understood, the families’ claims were unsubstantiated hearsay at best, and from demonstrably biased actors. Furthermore, their claims were contradicted by the available evidence. In the case of the Easter Sunday murders in Grapevine, Texas, Methvin reported to the FBI in a sworn statement that he had been asleep in the car all day while Bonnie played in the grass with a pet rabbit she had gifted to her mother, and that he was awakened by gunfire. Methvin’s statement jibes exactly with the sworn eyewitness accounts. Those include that of Jack Cook, who saw a male and female couple outside the car just prior to the shooting, as well as those of Schieffer and his two daughters, all of whom consistently stated that there were two shooters and that one of them was female — and matched Bonnie’s general description.

Also, the claim that there was a lone shooter using a Browning Automatic Rifle cannot be reconciled with the ballistics evidence from the scene — six large buckshot shotgun shells, five .45 auto pistol cartridges, and only one 30.06 shell casing, not to mention the wounds suffered by Wheeler and Murphy. Those findings also match the Schieffers’ testimony that the shooters used shotguns in their initial attack on the unsuspecting officers.

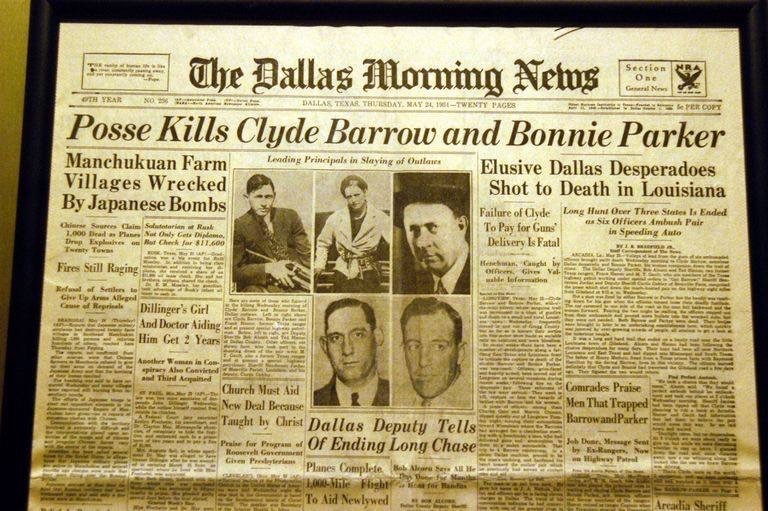

The deaths of Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow made headlines at The Dallas Morning News.

The deaths of Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow made headlines at The Dallas Morning News.

Still, there are those today — including a number of widely read published accounts — who passionately defend Bonnie Parker, often insisting that she “never fired a gun” at any point during the Barrow Gang crime spree. Some even go so far as to insist that she was “afraid” of guns. Yet, evidence and accounts of Bonnie’s involvement in shootouts and murders are as prolific and well-documented as that of Clyde’s. In fact, she’d only known Clyde for a few weeks when she snuck a pistol into him at the Waco, Texas, City Jail, facilitating his escape and the beginning of their life on the run.

In another example, a year before the Grapevine murders, a police raid on an apartment in Joplin, Missouri, led to one of many accounts of Bonnie discharging firearms with the gang. This time, Clyde, his brother Buck, and W.D. Jones fired on and killed Detective Harry McGinnis and Constable Wes Harryman. To aid their escape, Bonnie laid down cover fire with a Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR). The fusillade forced Highway Patrol Sergeant G.B. Kahler to seek cover behind an oak tree while the .30 caliber bullets shredded the other side. Trooper Kahler recounted, “That little red-headed woman filled my face with splinters on the other side of that tree with one of those damned guns.” More widows and orphans were created that day, so that Bonnie and Clyde could get away again. A month later in Lucerne, Indiana, Bonnie provided cover fire for the gang’s getaway, that time wounding two women. A week after that, in Okabena, Minnesota, she fired indiscriminately at civilians, barely missing a school bus full of children. Bonnie proved time and again that she was every bit as ruthless as Clyde, if not more.

The simple fact is that the protestations of Bonnie’s alleged innocence are, for the most part, strictly after-the-fact attempts to whitewash the brutal truth of the matter, rather than accurate or honest assessments of contemporary evidence and perspectives. They are also and often heavily influenced by romanticized popular culture and media depictions of the pair. The fact remains that Bonnie was no stranger to crime when she met Clyde, and she took to robbery and murder with great enthusiasm, according to numerous eyewitnesses from around the country. In fact, she was known to be so trigger-happy that on at least two occasions Clyde was known to have chastised her for committing murders even he hadn’t intended. One of those was shortly after the Grapevine murders, when she gunned down Oklahoma Constable Cal Campbell and then, at Clyde’s direction, they took Police Chief Percy Boyd as a hostage.

Given such documented instances, it might be that the story of Clyde having intended to take Wheeler and Murphy hostage may have been half-true, although it was Bonnie who “jumped the gun” rather than Henry Methvin, as the family tried to claim. The fact remains that Bonnie had long been attracted to and reveled in the criminal lifestyle, and she showed no regard or remorse for the gang’s many victims. To the contrary, she wrote many bragging letters and poems, repeatedly asserting her intention to continue their crime spree until death, insisting that she and Clyde would “go down together.”

Guns owned by Bonnie and Clyde on display.

Guns owned by Bonnie and Clyde on display.

The plain truth is that Parker and Barrow were not antiestablishment antiheroes, standing up against banks and oppressive authorities and sharing their booty with the poor and oppressed like some sort of 20th-century Robin Hoods. Their criminal careers predated the Great Depression by almost half a decade. Not to mention those tens of millions of Americans who survived such desperate times without ever robbing or murdering anyone. The fact is, Clyde has only been documented to have even attempted to rob less than a handful of banks during his eight-year criminal career, none of which resulted in a substantial payday. While Clyde was an excellent getaway driver, he was an ineffectual thief, burglar, and bank robber. His shortcomings in this regard are the principal reasons the gang lived by the seat of their pants and ran through members who quickly became disillusioned with his apparent lack of criminal acumen.

Under Clyde’s amateurish, hair-trigger leadership, the gang merely scraped by, primarily by stealing cars and robbing individuals, families, and small independent businesses struggling to stay afloat, often murdering their prey or responding law enforcement officers to avoid arrest. Quite simply, their motivation was that they preferred to steal rather than work, and to kill rather than risk being caught — as even Clyde’s own sister and mother attested to after his death. At Eastham Prison Farm, Clyde once had a fellow inmate chop off his toe with an ax so he could get transferred out of work detail. Bonnie had dreamed of being a Broadway or movie star (she adored Myrna Loy); front page photos, stories, and her own published poetry provided her the fan base she had dreamed of as an impoverished West Dallas girl. She called the American people who bought into the media depictions of the deadly duo as antiestablishment rebels with a cause “[her] public.”

The bottom line is that the contemporary evidence of Bonnie’s culpability at Grapevine — and many other violent encounters with the gang — includes the clear and consistent testimony of eyewitnesses to those murders, plus the ballistics analysis that matched Bonnie’s custom altered shotgun — a weapon she was frequently photographed with and that was found in the death car after the ambush. Various published claims that William Schieffer’s testimony was later “refuted” or “recanted” have failed to produce any contemporary evidence to support such contentions. Furthermore, Bonnie Parker was, in fact — and again, contrary to published claims — under indictment for the Grapevine murders before she died. Original documentation of this fact resurfaced in 2019, as part of an archival digitization project.

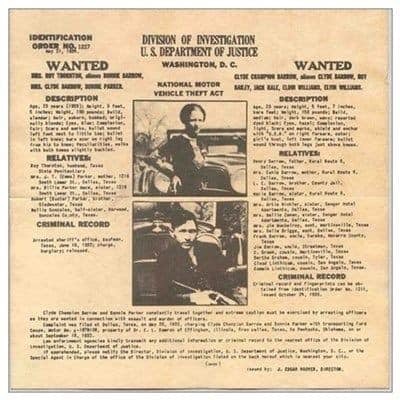

Wanted posters for Bonnie and Clyde distributed by the U.S. Department of Justice Division of Investigation.

Wanted posters for Bonnie and Clyde distributed by the U.S. Department of Justice Division of Investigation.

Romanticized spin by Bonnie-apologists regarding the Grapevine murders — such as assertions that the key eyewitness was “several hundred yards away” from the scene — lead them to erroneously conclude that Schieffer could not possibly have made a reliable identification. In fact, he had been as close as 10 yards from the killers at least at one point earlier in the day and was — along with his two daughters — only 100 yards distant and with an unobstructed view at the time of the murders. The three Schieffers provided investigating officers, the press, and later in court, consistent and detailed descriptions of the shooters and their activities leading up to and during the crime. As the people who were present the longest, closest to, and who had the clearest view of the scene, their key eyewitness accounts should not be discarded in favor of claims by those with dubious objectives and who were not present.

The fundamental question is, did Bonnie Parker pull the trigger at Grapevine, and during many of the gang’s other violent episodes? And the answer is yes. Just as for Clyde, all the physical, forensic, and eyewitness evidence from the time indicates that she did —despite the many mischaracterizations to the contrary. The only originating sources for such erroneous claims that she did not are the Barrow and Parker families, who were obviously not present at the scene and were not objective affiants.

Finally, the effort to dispute Bonnie’s role in Grapevine ignores her lengthy and violent criminal career. She was involved in at least 10 other shootings, two jail/prison breaks, up to 10 kidnappings, and more than a dozen armed robberies. She was even known to have pistol-whipped a female kidnap victim. Her crimes left at least six men dead and eight wounded, and left as many widows and even more children to survive without their husbands and fathers in the midst of the Great Depression.

One of the most influential sources of misinformation about Bonnie and Clyde is Arthur Penn’s celebrated 1967 film. A cinema landmark, Penn’s film used some real-life names but was never intended to document the real-life crimes and the very real human costs of the choices made by members of the Barrow Gang. As a result, and shortly after the film’s release, Frank Hamer’s fearless and implacable widow, Gladys, sued Warner Bros. and Penn over their fictionalized portrayal of her late husband. Warner Bros. chose to settle with the aggrieved family over those misrepresentations, and Penn personally offered a tearful apology at the settlement meeting.

Bonnie and Clyde embracing one another in a rare photo.

Bonnie and Clyde embracing one another in a rare photo.

Until recently, most modern Americans received what little they think they know about the homicidal duo from that work of movie fiction. Still others have been misled by those seeking to exonerate Bonnie out of some misplaced sympathy, often influenced by antiestablishment narratives or Parker family relations. Such efforts are particularly dubious given that, when provided the opportunity during her lifetime to “correct the record” from her point of view, Bonnie’s only concern was about being thought of as a woman who smoked cigars. This was in reference to a photo recovered and widely published after she had helped shoot their way out of yet another arrest attempt, in Missouri, in which she had posed with a cigar in her mouth while holding multiple guns. She offered no objections regarding the label of “gun moll” nor any denials of the many heinous crimes for which she was already accused.

Whatever the motivation, the effect of efforts to romanticize Bonnie and Clyde in a litany of articles, books, and even feature films over the decades is the erasure of the experiences, perspectives, and memory of the many victims and their families, thereby compounding the injustice inflicted upon them. Friends and family of Marie Tullis, highway patrolman Holloway Murphy’s fiancé, report that “she was never the same” and she never married. In the words of E.B. Wheeler’s widow, Doris, “[P]opular culture ... made heroes of the gang who killed my husband ... nobody ever thinks about those of us who were left behind.” Doris lived on, to the age of 96, but “the anguish never ended.”

Dr. Jody Edward Ginn is a former law enforcement investigator and U.S. Army veteran who works as the director of development for the Texas Rangers Hall of Fame and Museum, in Waco, Texas. Ginn has been a historical consultant to museums, educational institutions, and filmmakers, and is a former adjunct professor of history at Austin Community College. Ginn has authored publications on various Texas history topics, including “Texas Rangers in Myth and Memory,” in Texan Identities (UNT Press, 2016). Ginn’s latest book is East Texas Troubles: The Allred Rangers’ Cleanup of San Augustine (OU Press, 2019).

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Dr. Jody Edward Ginn