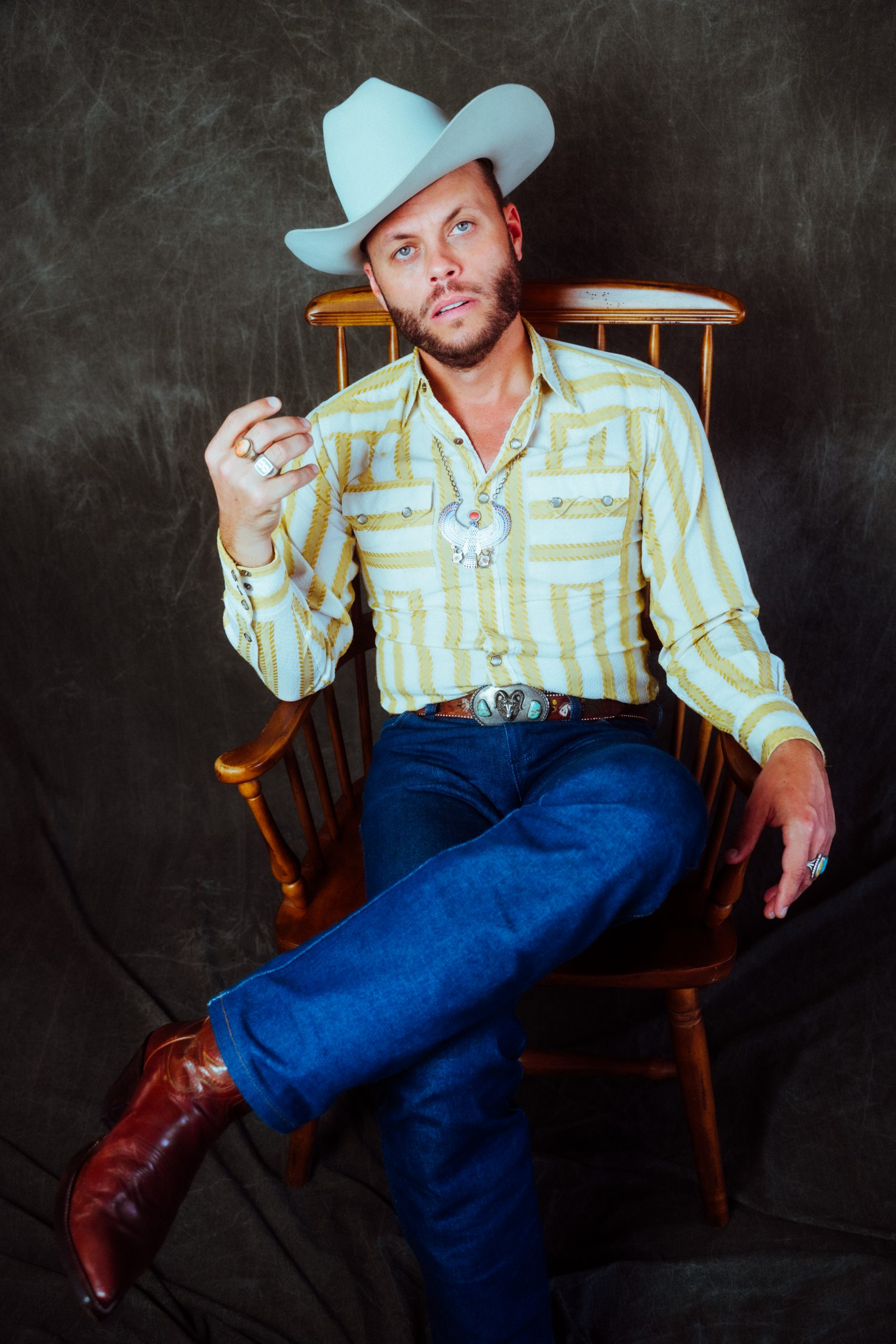

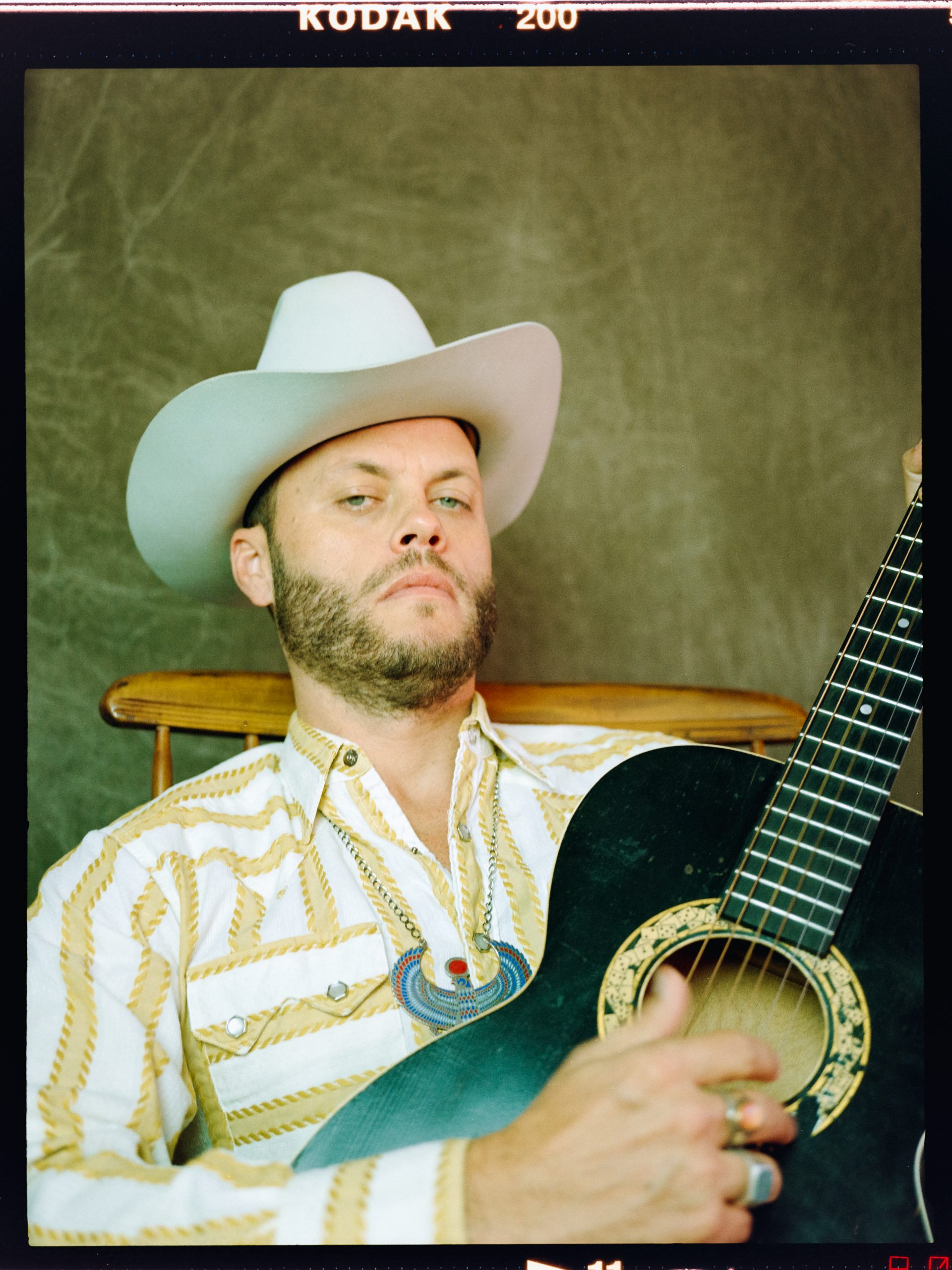

With vocal prowess and unparalleled vintage cowboy style, up-and-coming Texas crooner Charley Crockett is laying down the tracks of a lasting musical legacy.

Charley Crockett is the Cowboy Singer for the 21st century. He possesses a husky voice with a slight lisp that every now and then breaks — a honky-tonker with vulnerabilities. He’s immediately recognizable, just like you know it’s Willie by the first two notes on the guitar strings. “Cain’t” really is in his vocabulary, belying his South Texas roots; “warsh” most definitely isn’t. “No, sir. That’s some Panhandle s--t,” he said to me in all seriousness.

Listen close and you’ll pick up whiffs of old country legends like Ernest Tubb, George Jones, Lefty Frizzell, Hank Williams, Willie Nelson, and Jerry Reed, from whom Crockett borrows. Listen closer and you’ll discover an exceptionally suave crooner who has crafted an original sound he calls “Gulf & Western.”

With his Blue Drifters band and a work ethic that doesn’t know quit, he plays venues around the world and attracts audiences of all ages, all while cranking out records at a prodigious pace. Instead of starring in movies like the original Cowboy Singer, Gene Autry (another native Texan), he stars in a string of his own western-themed music videos. At 40, Charley Crockett is an overnight sensation who has burnished a legend that happens to be pretty much true — a genuine Cowboy Singer.

He was born in San Benito, in the Rio Grande Valley of far South Texas — hometown of Tejano music giant Freddy Fender — and raised in trailer homes nearby on South Padre Island and Los Fresnos before moving at age 9 with his divorced mother to Irving, just outside Dallas.

The singer part of the proposition came into focus during teenage summers spent in New Orleans with a favorite uncle who worked as a cook in the French Quarter. That’s where Charley first saw guitarists, rappers, trumpet players, sax players, drummers, and tap dancers performing on sidewalks and street corners, making all kinds of music. The fire was lit.

With a guitar his mom bought him at a pawn shop in Irving, he taught himself enough to try to play on the street himself. In New Orleans, he met a trumpet player named Charlie Mills who showed him how to play, where to play, when to play, and what to play if he wanted to fill his guitar case with bills and coins. He learned standards and popular songs that people would recognize: “Drivin’ Nails In My Coffin,” “Bill Bailey,” “Basin Street Blues,” “Bei Mir Bistu Shein.”

Busking provided the means to move around, which was his life for 10 years as he bounced from Dallas and New Orleans to New York, Copenhagen, Paris, Spain, and Morocco. Cowboys, including the Singing variety, are a restless breed. He worked the marijuana fields of northern California, transporting illicit loads to faraway destinations. He got involved with a Ponzi scheme that a stepbrother was running and almost went to prison. Hopping freights, hitching rides, and sleeping in strange places while dodging the law, he kept playing guitar, singing songs, and writing some too. He got good at it.

That decade of rambling and roaming has been followed by a decade of exceptional creativity and a whole lot of work: 12 albums, 200 playdates a year. Despite a past that didn’t have a whole lot of Western culture in it, his Texas roots played a big role in his jump from street to stage.

Charley Crockett reminded me of all that when I caught up with him in the hospitality room of the Whitewater Amphitheater on the banks of the Guadalupe River near New Braunfels, Texas, late last summer. He was finishing a plate of enchiladas alongside his fiancée, Taylor Grace, before playing the last gig of an extended U.S.-Canada run that started in late April. With an outside temperature of 105 degrees, everyone was staying indoors before hitting the outdoor stage.

Casual, pre-show Charley was a modern good ol’ boy in his green “Kiss My Bass” gimme cap, short-sleeve striped pearl-snap shirt, jeans, and pigskin boots.

It had been a year since we last talked. “How are you doing?” I asked.

“Well, I’ve been trying to answer your question ever since you posed it,” he answered with a straight face.

What question was that? (I tend to ask a lot of questions.)

“‘Are you going to transcend Texas music?’”

Oh, that question. Well?

“Well, I’m going to take Texas music with me to the world. It’s just got to be my brand of it.”

That was his acknowledgment that he’d climbed another step on the show business stairway, and he was still doing it his way.

He was big enough to perform in three-to-five-thousand-seat venues, a long way from when he would work Adair’s, the Pecan Lodge BBQ joint, a Deep Ellum barbershop, a public radio fundraiser, and a beer festival around Dallas over a long weekend.

In previous conversations, Charley talked my ear off, always sounding like a man on a mission trying to jam a whole lot into just a little bit. But here in a spacious, air-conditioned backstage area with all the creature comforts within reach — “Topo? Ranch water?” — and a luxurious touring bus parked outside (“I got it from Florida Coaches with Willie’s recommendation”), he was more relaxed, measured.

Years of playing on the street, years of playing with bands, appeared to be paying off.

“I just got lucky from where I was stepping off of the street and learning how to front bands and play clubs, mostly through informal blues jams around Dallas, Fort Worth, New Orleans, and in Austin,” Crockett said.

“I remember, s--t, walking into Sam’s Town Point [in Austin] for Breck English’s blues jam. I was afraid to get on that damn stage because I was such an itinerant.”

He said he’d been nervous when he first started playing big stages, but wasn’t anymore.

Bobby Cochran met Charley at an events center in Ukiah, California, near the marijuana fields of Mendocino County, back in 2012. “He came up with a buddy of his and asked if he could play during our band’s set break,” Cochran recalled. “A few months later, he came into this coffeehouse I managed and asked if he could play in the corner. A week later he came in and played for the afternoon. Mostly it was us, the employees, and him back in the corner. It wasn’t long after that he was collaborating with Kyle Madrigal, a guy I played with in a band. He recorded his first album at Kyle’s house.”

Madrigal recorded Charley singing and playing guitar, then added his own bass and Cochran’s drums. That was the foundation of A Stolen Jewel, Charley Crockett’s first album.

“I got a good vibe from him,” Cochran said. “He seemed like a solid dude, warm, friendly.

“That was the deal: He’d disappear back to Texas, come back to town, play a handful of gigs, hang out, then disappear again. Then he found his band in Dallas.”

The singer had met guitarist Alexis Sanchez at a Dallas blues jam. Even though Sanchez fronted his own band, Charley talked him into joining forces. Sanchez admired his new collaborator’s hustle, which included leaving giveaway copies of his record in the restrooms of clubs where he was playing. He played fair.

Sanchez: “Whatever he’d make from tips or selling CDs, he’d split it with the band.”

“Those guys would be with him whenever he’d come back to Mendo after that,” said Bobby Cochran. “That was the end of my playing in his band. Once he found what he wanted, he was locked into it.”

Charley dodged jail time again, this time for his involvement in marijuana production. He got a $10,000 fine when he showed the judge the record he had just made. He wasn’t an outlaw. He was legit.

The artist first caught my ears and eyes with the video of his original version of “Trinity River,” where he sports a fedora and wingtips, all vintaged-out like a sideman for the Squirrel Nut Zippers, while playing on a Deep Ellum street corner and inside the studio of KNON, Dallas’ cool community radio station. No one ever sung about the Trinity River. The only song I knew was by Oak Cliff ’s T-Bone Walker whose very first record featured “Trinity River Blues,” and released in 1929, years before Walker became the king of electric blues guitar. T-Bone Walker sang, “That dirty, dirty river sure has done me wrong.” Charley Crockett sang his Trinity was the “dirty little river gonna get me clean.”

Crockett said he was in New York City crashing in a Brooklyn indie band’s rehearsal space when T-Bone Walker made him realize the best, easiest way to explain himself.

“I was flipping through an old blues reel book, seeing all these blues names,” he said. “I remember stopping on T-Bone Walker and looking at him, looking at the song, the little chord chart that was denoting the unique style of kind of jazzy blues chord, the shapes he was holding. It was surprising because I’d been holding chords that way since I was a kid. I just never knew what they were called.

“That was the day I no longer was running away from

Texas. I turned around and realized that it was just who I

was.” He affirmed his Texan-ness in a Q&A for Texas Highways magazine: “I got all these managers calling me saying, ‘Look,

Charley, you know the world is bigger than Texas.’ I know this sounds brash, but this is the policy that I have adopted going forward: The world is not bigger than Texas. There is only Texas, and we take Texas to the world. That’s what I have to do. That’s how Stevie Ray Vaughan did it, that’s how ZZ Top did it, that’s how Willie done it, that’s how Selena did it, that’s how Freddy Fender did it.”

Sharing big stages with two of those role models — Willie Nelson and Billy Gibbons of ZZ Top — on the 2022 Outlaw Music Festival tour provided more serious schooling.

That was the day I no longer was running away from Texas. I turned around and realized that it was just who I was.

“When I was out with Willie on the Outlaw Tour, one of the coolest things about it, every time I was near Willie it felt like a cultural event,” he said. “His 90th birthday was absolutely a singular cultural event.” Billy Gibbons — whose band ZZ Top blazed their way into rock arenas wearing cowboy hats, sparkly Nudie suits, and boots, selling an idea of Texas — offered direct advice. “We were talking after one of the shows,” Charley said. Gibbons told him, “Man, that minor [chord] s--t you’re doing with your guitar ... don’t let anybody talk you out of that. Keep doing all that minor s--t.” Charley beamed.

“I end up eating off the plate of a simple thing like that for the rest of my life,” he said, reaching deep back to when his legend began. “There was a woman on the street in New Orleans when I was much younger. They called her Angel. She said, ‘Baby, you got a beautiful voice, but you need to learn this one thing. You got to start low if you want to get high.’ She was telling me that I needed to develop and use the power of the lower part of my voice for my diaphragm.” His band, the Blue Drifters, became fully formed in 2017 with the addition of Kullen Fox, a multi-instrumentalist who plays trumpet and accordion as well as keyboards. He’s from Austin, where Charley had relocated.

Crockett’s version of “Jamestown Ferry,” an early ’70s country hit for 13-year-old Tanya Tucker, got traction on social media when the track was released on Lil’G.L.’s Honky Tonk Jubilee, an album of old country covers, released in 2017. More country classics — George Jones’ “The Race Is On,” Ernest Tubb’s “Saturday Satan, Sunday Saint,” Tom T. Hall’s “That’s How I Got to Memphis,” and Danny O’Keefe’s “Good Time Charlie’s Got the Blues” — appeared on 2018’s Lil G.L.’s Blues Bonanza album of covers, along with Crockett blues favorites “T-Bone Shuffle” and “Travelin’ Blues” by T-Bone Walker, and Jimmy Reed’s “Bright Lights, Big City.”

An extended tour that year, opening for the Turnpike Troubadours, the hugely popular Red Dirt indie country band from Oklahoma, tapped into what would become his core audience.

Mark Neill, who had co-produced The Black Keys’ retro rock, reached out to Crockett after hearing some tapes, luring him to his Georgia studio with the promise of making “a real country record.” Two breakthrough albums came out of the collaboration, Welcome to Hard Times and Music City USA, Charley’s country-est records yet. Just as significantly, Neill stressed to Crockett, it’s important to think of songs cinematically.

Lil G.L. Presents Ten For Slim: Charley Crockett Sings James Hand took the hard country affinity to the extreme, paying tribute to the late James “Slim” Hand, an older Texas honky-tonker who became Charley’s mentor and muse for a spell. Hand became such a presence, he played the lead character in the video for “That’s How I Got To Memphis.” The band took to calling him “the man from Waco,” the inspiration for the title of Crockett’s next album, released in 2022.

The Man From Waco, recorded with the Blue Drifters, was supposed to be a demo produced by Bruce Robison at his studio in Lockhart outside of Austin. The tracks would get the full studio treatment later, most likely with mega-producer Rick Rubin at his Shangri-La Studios. Crockett had signed a publishing deal with Rubin, but Rubin as producer would have to wait. The demo was so good, it had to be an album.

The Man From Waco is a western saga, from the first twangs introducing the title track to the lonely Marty Robbins’ trumpet lines. Places that don’t get mythologized much like Waco and Odessa are enshrined. There is a sweet murder ballad, “July Jackson,” a new version of “Trinity River” that passes for swinging jazz, and a nod to his personal marketing strategy, “Name On A Billboard.”

In September 2023, Live from the Ryman, documenting his first performance at the Mother Church of Country Music in Nashville, was released as an album and video, capturing Crockett’s smoldering, restrained appeal. If bending the knees was good enough for Hank Williams and swiveling the hips defined Elvis, those stage moves were good enough for him.

That same month, he released a track “Killers of The Flower Moon,” produced by T-Bone Burnett, based on his reading of the book about the murders of Osage people in Oklahoma for oil, the basis for director Martin Scorsese’s movie. The single coincided with the film’s release. That was followed a couple of weeks later by the exclusive Amazon release of Crockett’s renderings of Link Wray’s “Fire & Brimstone” and “Jukebox Mama” from an obscure album, timed with the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame’s induction of Wray, the distinctive “Rumble” guitar instrumentalist and the first Native American honored by the institution.

The latest album, $10 Cowboy, was recorded at Arlyn Studios in Austin with the Blue Drifters and several outside players, with longtime collaborator Billy Horton assisting on production. It’s a cohesive collection of songs with a big sound — voice out front, steel guitar floating around ethereally in the background, horns providing a punchy response to vocal calls. Darkness lurks beneath the surface, pushed by Sanchez’s spaghetti western guitar and Fox’s soul organ fills: undelivered promises in “America,” the post-classic decadent imagery of “Crystal Chandeliers,” jackals roaming the valley in “Solitary Road,” the refrain of “Tired Again” ... The street took all my money. The street took all my money. The street took All. My. Money!

A $10 cowboy singer, it turns out, is a lot like a $10 cowboy, according to the last lines of the album’s title track: When I was out there on those street corners, standing behind this guitar, ten dollars was a whole lot of money. Cowboys, cowboy singers are both highly hazardous occupations. Look out!

The notion of “Charley Crockett, Cowboy Singer” came into focus in 2019, right after the crooner almost died.

“I had an ablation and then open-heart surgery [to repair fused aortic valves] a week apart,” he said matter-of-factly, acknowledging a congenital condition. After recovering, he returned to Mendo where Bobby Cochran shot a simple video of Charley riding a bicycle around rural Mendocino Country, wearing a cowboy hat, lip-synching to the catchy, accordion-driven tune “River of Sorrow” from the album The Valley.

In early 2020, COVID hit, shows were canceled, and Crockett’s career went on hold. With the album Welcome to Hard Times scheduled for July release, Crockett asked Cochran to drive around the Southwest and make some videos.

Charley, his fiancée, and Cochran hit the road. “The best thing we could do was be out in the middle of nowhere sleeping in the truck, pitching a tent, because it’s the damn pandemic,” Charley said. “You couldn’t stay in a hotel if you tried. We were just camping out and hitting those national parks and all those really beautiful places I’d seen over the years.”

“It was insane,” recalled Cochran. “We started in Bishop [California], went to Death Valley, Zion, the north rim of the Grand Canyon, New Mexico. We filmed ‘Fool Somebody Else’ at the Opera House of Amargosa Hotel near Death Valley, It was closed because of COVID so we decided to film outside until this young guy, who turned out to be the caretaker at the hotel, walked over and asked, ‘What are y’all doing?’ We kind of explained and he went, ‘Oh, you’re Charley Crockett! I saw you in Indiana a year ago. Sure, you guys can go in and film. Right on.’ ”

The footage shot by Bobby Cochran completed Crockett’s transformation to Cowboy Singer. The sprawling landscapes fit his songs to a T. Each video is introduced by the shot of a rotary telephone or pay phone out in the middle of nowhere, ringing.

What does the phone imagery mean?

“Okay, I’m going to tell you the truth,” Charley said, drawing closer, speaking conspiratorially. “All right. You see how that cord’s hanging out of the back of that phone unplugged? That’s so all my real friends can get through. It rings all the time.”

He grinned. I would just have to abide by the mystery. His imagery set to music was catching on. The Lone Star Film Festival in Fort Worth recognized him for his western-themed videos. December and January were spent along the 411 mile route between Austin and the High Plains town of Littlefield, Texas, home of Waylon Jennings and home of Waymore’s Drive-Thru Liquor Store and Museum, run by James Jennings, Waylon’s brother. Charley Crockett was filming his first full-length movie.

When I was playing on the street in New Orleans, the best gig that I could imagine myself getting was the 4 p.m. gig at the Apple Barrel.

The day before our visit, Charley had been in New Orleans at Esplanade Studios recording those Link Wray tracks that turned into his first Amazon exclusive (all rights reverted back to him at the first of the year, he pointed out proudly. )

While in the Big Easy, Charley also dropped by the Apple Barrel on Frenchmen Street. “When I was playing on the street in New Orleans, the best gig that I could imagine myself getting was the 4 p.m. gig at the Apple Barrel,” he said. “I thought that that was the cream of the crop. [New Orleans hoodoo blues guitarist] Coco Robicheaux, he died in that bar.

“He died sitting in the bar stool right about where I was sitting when the bartender was telling me, ‘The last thing [Coco] said was the next round’s on me.’ That bartender made a funny joke.

“He said, ‘That’s the first round that was ever on him.’ ”

Charley was recognized at the Apple Barrel and recognized on the streets of New Orleans, where he’s known as a blues singer. He’s still a NOLA local, just like he’s a Dallas local and an Austin local. But on a global scale, he’s a Cowboy Singer now.

Was he getting recognized a lot?

“Everywhere,” he said flatly.

Is it a hassle?

“It can be,” he admitted in a plaintive voice before catching himself and straightening up. “Hey man, we signed up for this.”

Yep, the Cowboy Singer sure did.

Charley Crockett’s album $10 Cowboy comes out in April. Find out more at charleycrockett.com.

From our April 2024 issue.

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy Jackie Lee Young