The Tejana-Indigenous multihyphenate currently is directing the play 26 Miles at Main Street Theater in Houston.

Her name may not be familiar, but you’d likely recognize her face, almost immediately, if you saw Amelia Rico in either Dark Winds or 1923.

In Dark Winds, the San Antonio-born Tejana-Indigenous actress made an indelible impact as Ada Growing Thunder, a spell-casting witchy woman who’s sufficiently intimidating to stop the normally formidable Sgt. Bernadette Manuelito (Jessica Matten) dead in her tracks with a stern look, a pointed finger, a whiff of magic dust — and a haughty farewell of “Walk in beauty, Officer!” Just how scary was she? Put it this way: We’re supposed to think Ada perished in a housefire the fifth episode — but damned if we weren’t fully expecting her to somehow show up in Episode 6.

Rico was on the side of the angels in the Taylor Sheridan-produced 1923 as Issaxche, grandmother of Teonna Rainwater (Aminah Nieves), a brave runaway from an Indian School where she vengefully spilled the blood of two tormentors before she vamoosed. Unfortunately, lawmen figured Teonna might be seeking refuge at her grandmother’s home, and showed up on Issaxche’s doorstep. Even more unfortunately, they cavalierly swatted the poor woman out of their way, causing her to have a fatal head injury.

A resident of Houston ever since she attended University of Houston, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in Theatre Acting/Directing, Rico boasts a resume that also lists roles on the TV series Yellowstone, Grey’s Anatomy and Walker, and in the 2018 indie film Rich Kids.

She’s currently returning to her roots in theater as director of 26 Miles, a play by Pulitzer Prize-winner Quiara Alegría Hudes (Water by the Spoonful) that she is staging at Houston’s prestigious Main Street Theater. The production is set to open Saturday, Feb. 10, and continue through March 3.

The plot: “The custody battle left them estranged for eight years. The road trip destination is two thousand miles across the country. The mother’s skin is brown; the teenage daughter’s skin is white. So what if reality’s nipping at their heels? This reunited pair runs frantically and hilariously from the secrets in their lives, hunting valuable antiques, chasing arctic explorers, getting lost in Wyoming’s wilderness – and finding their way again as mother and daughter.”

We were able to catch up with Amelia Rico between rehearsals for 26 Miles, to talk about her life and work. Here are some highlights from our conversation, edited for brevity and clarity.

Cowboys & Indians: OK, so you’re traveling on a plane, and someone sits next to you — and they recognize you from television.

Amelia Rico: [Laughs] That’s actually happened.

C&I: And they ask, “What are you up to now?” And you respond, “Well, I’m actually directing a play, Quiara Alegría Hudes’ 26 Miles, in Houston.” And they say, “What’s it about?” And you say…

Rico: Well, on the surface it’s about a mother and daughter reconnecting on this road trip. But of course, my job as a director is to find what’s underneath that surface. And to me, I feel the overall theme is, it’s about reclaiming your identity, reconnecting with your ancestry.

Because the young girl in the play, she’s white passing. She lived with her father, who's Jewish, so she hasn’t been acclimated to the culture of her mother, who is Cuban and of Arawak Indian ancestors — Taino ancestry, really. And so when I saw there was this line in the script where the mother says, “Your blood is my blood. Your skin is my skin. Your grandfather was full-blooded Arawak,” I went straight to Google, looked up, started researching the Arawak culture, and I found that that’s sort of a generalization word for Taino, which are the first contacts Natives down in Cuba and in the Caribbean, that whole area.

So I really started to research that culture and that specific group of Indigenous people. And I found such a rich way to tell the story, because the play starts, first of all, with a monologue from the young girl to the audience. And you don’t have any kind of grounding to that monologue, so it feels sort of super purposeless. You don’t understand what is the point of this story, how does it connect to the rest of the play?

But once I had that grounding of culture, I knew, OK, this is an Indigenous story, and Indigenous people tell their myths, tell their stories. And teach. They teach their young, they tell their stories in a very theatrical storytelling ceremonial way. So once I start getting those ceremonial, storytelling, Indigenous elements into the overall play, then I really started to connect all the pieces. That’s where it started. It gave me my theme of reclaiming Indigeneity, reclaiming your ancestry, and not feeling, “Oh, I don’t look Native enough, I’m not with my mother all the time. I don’t feel connected to that.” Now she’s going to feel connected to that community.

C&I: Did the plot element of mixed ancestry have a special meaning for you?

Rico: Yes, for a long time. As a Tejana, I was raised to believe I’m specifically Mexican. Like, I’m Mexican. I'm from Mexico. My family is from Mexico. And Mexico is seen as its own thing, very specific, and not attached at all to Indigenous culture. But even as a child, growing up in a Latin community, going to school with people that also see themselves as Mexican or Latinos or Chicanos — I always felt different. I felt outside of that. I was made fun of for my straight hair. I was made fun of for my slanted, almond shaped eyes. I would be called Asian a lot of the times for my darker complexion. And I never really felt connected to that as just seeing myself as Mexican.

People would ask me all the time, “You don't speak Spanish. Why don't you speak Spanish?” Or even if they didn't know me at all and they'd see me, they’d be like, “What are you?” I get that question a lot. “What are you?” Because they couldn't really place me as any one specific ethnicity.

At first, I was kind of offended. Why are people always asking me “What are you?” And then I started asking myself, “Well, what am I? That's actually a valid question. What am I? Let me start really digging deep.” And when I started to dig deeper into my ancestry and found that my grandmother actually was born in Lytle, Texas. She and a lot of her family were from there — and some of them, yes, were just south of the border. My grandfather’s family goes back to San Luis Potosi, which is still North Mexico, but a little closer to Central Mexico.

But then I started to realize, OK, when you look at the history of Mexico, we have Indigenous communities all over Mexico, all over Texas, all over America, all over North and South America and Central America. And we have an integration happening. So unlike with the Navajo and with the northern tribes who got separated and segregated and put into reservations, the natives of South Texas and of Mexico got integrated into Spanish.

So I’ve been trying to figure out how do you identify when you don’t have a tribe? My tribe, Uto-Aztecan. was of course lost in colonization. That's something you discover when you start looking at the Mexican tribes — there are very few that still survive, that survived colonization. Most people integrated, or just went away, were killed off or what have you. And it gets difficult because I don't have a native card. I can’t get a native card, because I don’t have any tribes where I can go through those lines, go through that red tape, of getting a native card. Because getting a native card, that’s something that was created by American government to put you in a certain box or put you in a certain element. And with us, because we integrated with the Spanish culture, we don't have any of that.

C&I: On the other hand — and I know this may be cold comfort in some ways — but your mixed ancestry has helped you get cast in a wider variety of roles, right?

Rico: Sure. Yes. Once I started to really dig deeper into my ancestry, I started to receive more opportunities because then I was reclaiming something that was mine. And I felt for once like myself. I felt like I wasn’t putting anything on. I wasn’t trying to be something that was expected of me. For a long time, I was trying to learn Spanish because everybody kept saying, “Well, you have to know Spanish because you’re Mexican. You’ll get more roles.”

And one of my first kind of bigger roles was a Spanish-speaking mother in a movie called Rich Kids. I loved that role. I had a great time with the filmmakers. I still speak to them a lot. But one of my second would-be roles would’ve been a Spanish speaking-maid that I was offered without having to audition. Just from seeing my role on Rich Kids, somebody was going to give me a straight to offer, no audition, a Spanish-speaking maid. And I turned it down because I was like, I didn’t want that to be my brand. I didn’t want that to have two things under my belt where I’m a Spanish-speaking mother type character or caretaker.

Was that a good choice? I was worried about it for a long time, and I spoke to my husband about it, and we really had to think about what’s going to be best for me. And even though I was scared about it for a while, in the end, I ended up getting Yellowstone, which was filmed at the same time as that indie film. So if I had said yes, I would not have been available for Yellowstone…

C&I: And missed your chance to enter the Taylor Sheridan Universe.

Rico: [Laughs] Yes. But also, that opened doors to Grey’s Anatomy, to Dark Winds, and to 1923. And so sometimes it’s good to say no. You just have to know yourself, know what you're going for.

C&I: Speaking of Yellowstone and 1923, there are times when I suspect Taylor Sheridan keeps a close eye on everyone he ever casts in anything, even day players or people with walk-on parts, and always keeps them in mind for his next project.

Rico: I think that’s how it works for any director, really. If you find somebody you like to work with. and you feel like they bring something to the table, then you’re going to want to work with him again. And I was very lucky that he knew my work and he handpicked me for 1923. I wasn’t old enough to play that role. But when I was in the make-up chair, the hair stylist said that Taylor Sheridan had called him and told him, “There’s an actress I really want to cast for this role, but she’s not old enough to play the role. Would you be able to make her look older with hair extensions, whatever, to give her an older appearance?”

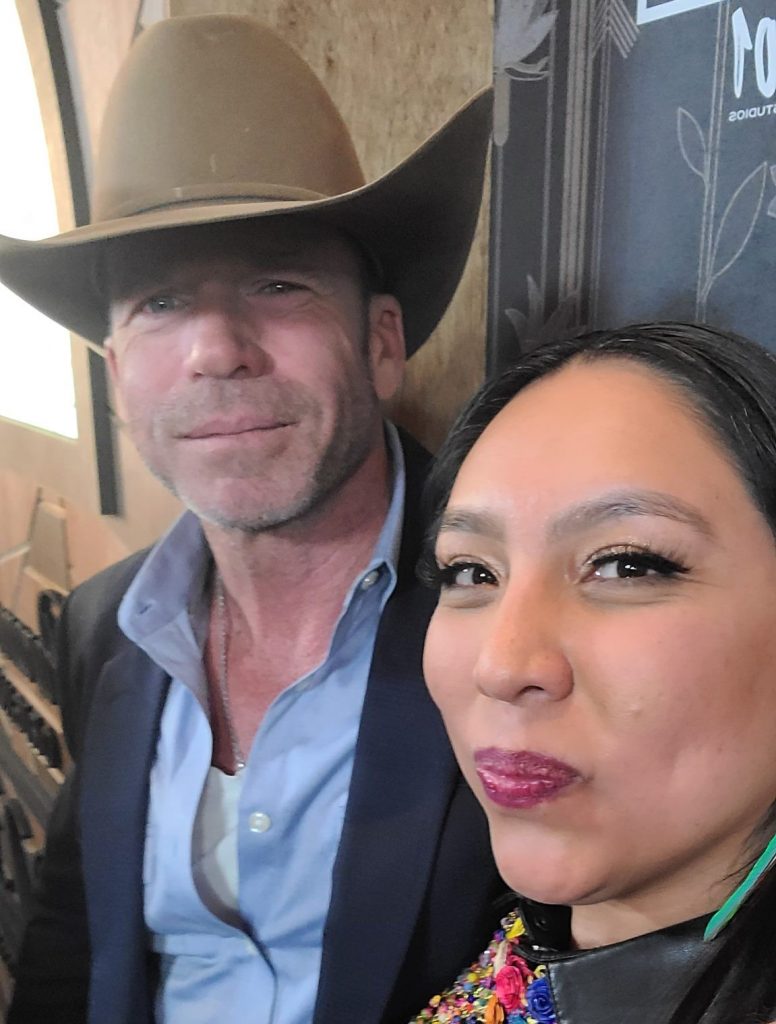

“And the same thing with the makeup artist. Taylor had made sure his staff was going to be up for the task to make me look older, because he wanted me for that role. He knew I wasn’t old enough, but there’s something he could do that maybe could be done about that. So that made me feel like, “Oh, wow, that's very nice” So at the premiere in Las Vegas, I went up to him and I was like, “Hi, Taylor. I play Issaxche. And he was like, “I know who you are. I cast you.” And I was like, “Oh, yeah, okay.”

C&I: So one role really can lead to another?

Rico: With a lot of actors, sometimes they don’t realize the impact they have on the people that see them. In Yellowstone, I was in a little co-star role, so you would think, “Oh, Taylor Sheridan’s not going to notice me. That's not anything.” But obviously that helped me in the end. And even in Grey’s Anatomy, I remember standing outside Prospect Studios waiting to go in. I didn't want to go in too early, so I was just waiting out there. And someone passed by me, and then they passed by me again, and they stopped and said, “Are you Amelia Rico?” And I hadn’t really done much at this point, so I’m not someone that someone’s going to recognize. Even now, I’m not someone that’s someone’s going to just stop and recognize.”

C&I: Well, except maybe when you’re seated next to them on a plane.

Rico: [Laughs] Well, anyway, I told her yes, and she’s like, “Oh, I’m the writer of this episode. I’m so excited to have you here.” And she was talking to me. Because even the writers, they get people’s head shots. And so you never know who’s going to see your work, or see your self-tape. That’s one thing I tell my actors. I have a weekly acting class, and one thing I always tell my students is, you don’t know who you’re connecting with, so you need to make sure that, whatever you put out there in the world, it’s your best. That it’s something you can be proud of. As long as you’re proud of it, you’ll reach the right people.

C&I: Finally, is there ever a downside to someone recognizing you for your work? Like, after Dark Winds, did people you meet ever appear scared you were going to blow dust their way and put a hex on them?

Rico: That’s so funny, because I remember when I was doing 1923 and I was out just hiking, I ran into a couple of people on my hike, and we kind of started hiking together because we were afraid. We had heard some kind of wild animal was in the area, so we were like, “There's strength in numbers, so let’s hike together.” So we started chatting, and they asked why I was there, and I said, “Oh, I’m here for a role in 1923.” And one of them was like, “Oh, I’m an extra in 1923.” So we started talking about it, and I told him how I was in Dark Winds, and he was like, “Oh yes, I remember.” And then he said, “Oh my God, they did a good job on your makeup. You looked scary.” I was like, “They didn’t put any makeup on me.”

C&I: Oops!

Rico: Yeah, they literally just put SPF sunscreen on me, just something to help me from getting a sunburn, and then they would just send me on my way. So I thought that was hilarious, and I started laughing. He was like, “I’m so sorry. I just put my foot in my mouth.” I was like, “No, that’s hilarious.” Because it just goes to show that my acting was enough. Just the change in my face, change in my demeanor, and how I put that out there in my role made it look like my face changed. He thought I had prosthetics or something. He thought I had major makeup to make me look scary. But he was looking at me and he didn’t see that in me as a person. But in the role, he saw me as this really scary creature.

C&I: Hey, that’s why they call it acting.

Rico: It’s like I told him: “Don’t feel like you offended me. I feel flattered. I feel flattered by that. It means I did my job. I did a good job.”