When archives of the late great filmmaker Sam Peckinpah were nearly lost, the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum rode to the rescue.

Maverick filmmaker Sam Peckinpah would have been 99 in 2024. Best known for his westerns and other classic films — The Wild Bunch, Ride the High Country, and Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid, to name a few — the controversial screenwriter and director died almost 40 years ago, but critical fascination with him and his oeuvre has only grown. A collection of Peckinpah artifacts and archives acquired by the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in late 2023 will shed new light on the filmmaker sometimes referred to as Bloody Sam, an unfortunate nickname for a cinematic poet whose keen eye did not overlook darker aspects of the American West.

The museum was already home to major collections related to mainstream western stars such as John Wayne, Barbara Stanwyck, Walter Brennan, and Roy Rogers. “But the great thing about the Sam collection,” says Michael R. Grauer, McCasland Chair of Cowboy Culture at the museum, “is that it’s a foil to the Singing Cowboy, clean-as-a-whistle Roy Rogers. Sam’s the outsider western guy. We’ve done really poorly with what I call the ‘brown westerns,’ the revisonist and the antihero westerns.”

That the collection even made its way to safe confines in Oklahoma City is something of a miracle. It almost wound up in the Livingston, Montana, city dump. Patty Miller and her husband owned the town’s historic Murray Hotel. Peckinpah had a trailer house in Malibu, bunked at the L.A. home of film composer Jerry Fielding and his wife, Camille, and spent time in Mexico, but he considered his third-floor suite at the Murray to be home from the mid-1970s until his death — at age 59 after decades of alcohol and other addictions — on December 28, 1984. He housed his business operations in other rooms at the hotel. Peckinpah also owned a cabin on land on Sixmile Creek outside Livingston, adjacent to the ranch of actor Warren Oates, a friend and collaborator. Miller felt close to Peckinpah, although it was a friendship tinged with sadness.

“His demons were in the bottle,” she wrote in a memoir, “and in other bad habits picked up way back.” The worst of those “other bad habits” was cocaine. In the 1970s, Livingston was home to a free-spirited community of young authors, artists, and filmmakers. Drugs were not hard to come by. Peckinpah was considerably older, but he could indulge himself with the best of them.

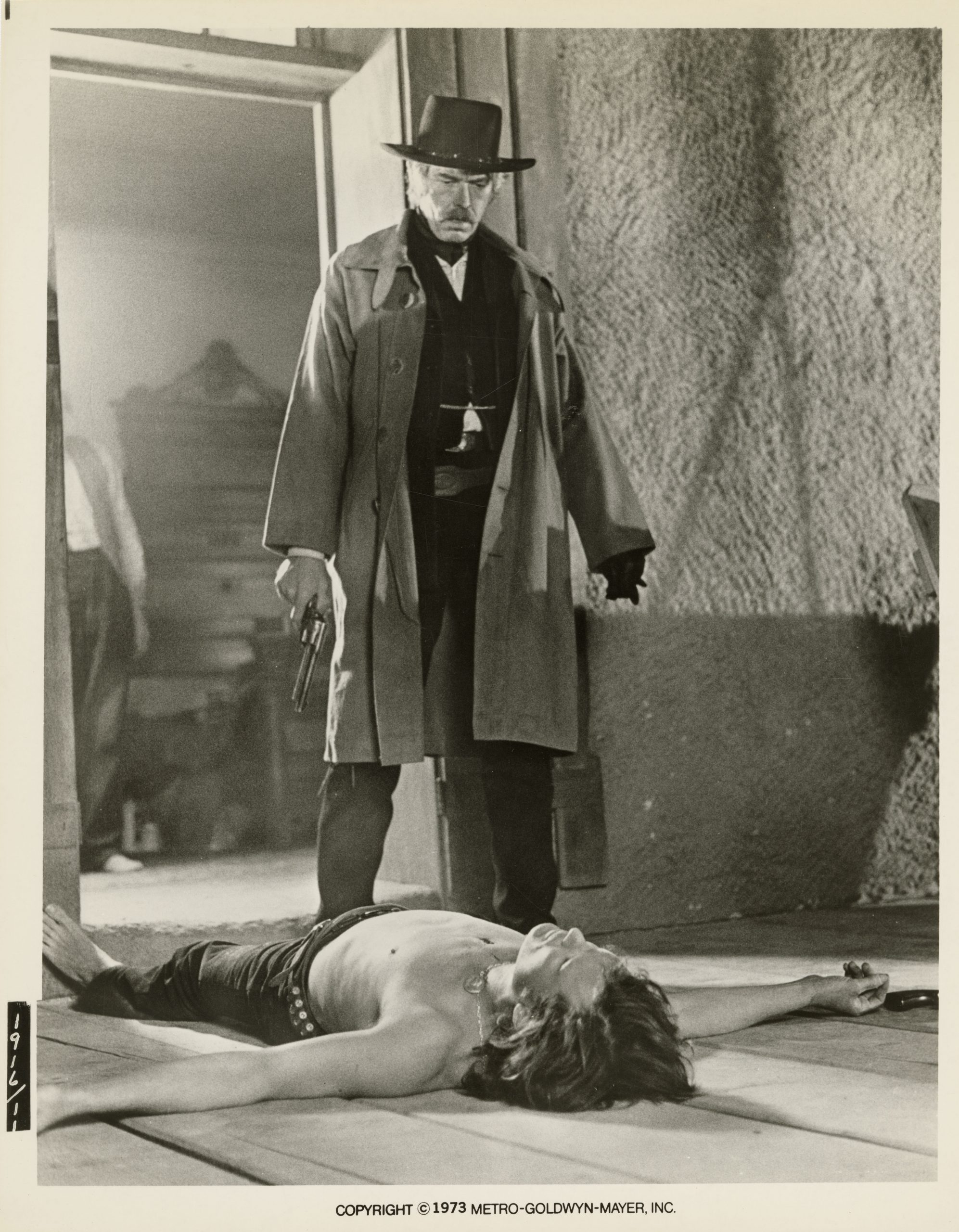

Patt Garrett and Billy the Kid, 1973 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Digital Reproduction of Film of Film Still Glenn D. Shirley Western Americana Collection, Dickinson Research Center, RC2006.067.2.02492.

Patt Garrett and Billy the Kid, 1973 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Digital Reproduction of Film of Film Still Glenn D. Shirley Western Americana Collection, Dickinson Research Center, RC2006.067.2.02492.

Regardless of Peckinpah’s excesses, Miller felt the need to protect the legacy of her friend, who called her “Boss Lady.” She rescued box after box of his work files and his personal artifacts from becoming trash-truck fodder after representatives of Peckinpah’s estate decided they had no value. Miller knew they were anything but worthless. She stored it all away in Livingston for decades.

Fast-forward 30 years. Director Monte Hellman — a friend, housemate, and mentor of Lathan McKay’s — shared an online photo of a pair of boots custom-made for Peckinpah. McKay is a film and television producer, historian, and co-founder of the Evel Knievel Museum. As a 1970s-era cinephile, he’s long been immersed in Peckinpah’s work. “I think of Sam Peckinpah as the Evel Knievel of filmmakers,” McKay says. “There is a deep kinship among mavericks, and, when you look closely, you see these parallels that thread together extraordinary legends and legacies.”

The photo of the boots led McKay to track down Miller, and he began to buy the collection piecemeal over several years. Once he had it secured, he began looking for a permanent home. He approached Garner Simmons, author of Peckinpah: A Portrait in Montage, an essential biography of the director. Simmons recommended the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. He knew that in the early 1980s the museum, when it was still known as the Cowboy Hall of Fame, had awarded Peckinpah one of its coveted Bronze Wrangler Awards for lifetime achievement. The recognition meant a great deal to Sam. “Make sure all my prints, papers, everything goes to them when I pass,” Peckinpah told his video archivist and friend Don Hyde. “I don’t want the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to have any of it. We have no use for each other. The Cowboy Hall of Fame is the only group like that that has ever recognized me for who I am.”

Peckinpah’s survivors ended up giving many of his papers to the Academy’s Margaret Herrick Library. But the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum’s acquisition of the artifacts and files rescued from the Murray Hotel will ensure that Peckinpah’s own legacy wishes expressed to Hyde will at least in part come true.

“We need historians, students, and scholars to come here and study Peckinpah’s stuff,” Grauer says. “That’s the best way for Sam to be honored.”

Search the Sam Peckinpah Collection and the Sam Peckinpah Western Film Collection.

This article appears in our January 2024 issue.

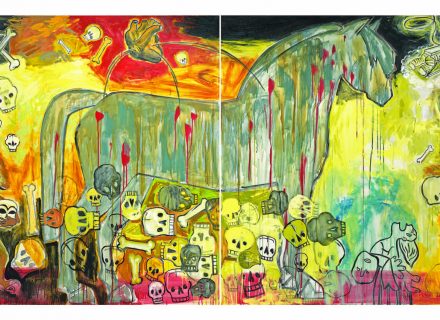

Lead Image: Pat Garrett and Billy The Kid, 1973 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Digital Reproduction Of Film Still Glenn D. Shirley Western Americana Collection, Dickinson Research Center, RC2006.067.2.02489-02.