Answering the call of the desert, Georgia O’Keeffe traded the frenzy of New York City for a life of solitude at a pair of New Mexico properties and become a creative force for all time.

When Georgia O’Keeffe made the 60-mile trek from her home and studio in Abiquiú to Santa Fe for health reasons back in 1984, she fully expected to come back. Sadly, she passed away two years later, at the age of 98, without a single return trip. That means that, unlike many homes-turned-museums, her residence remains largely as it was the day she left it.

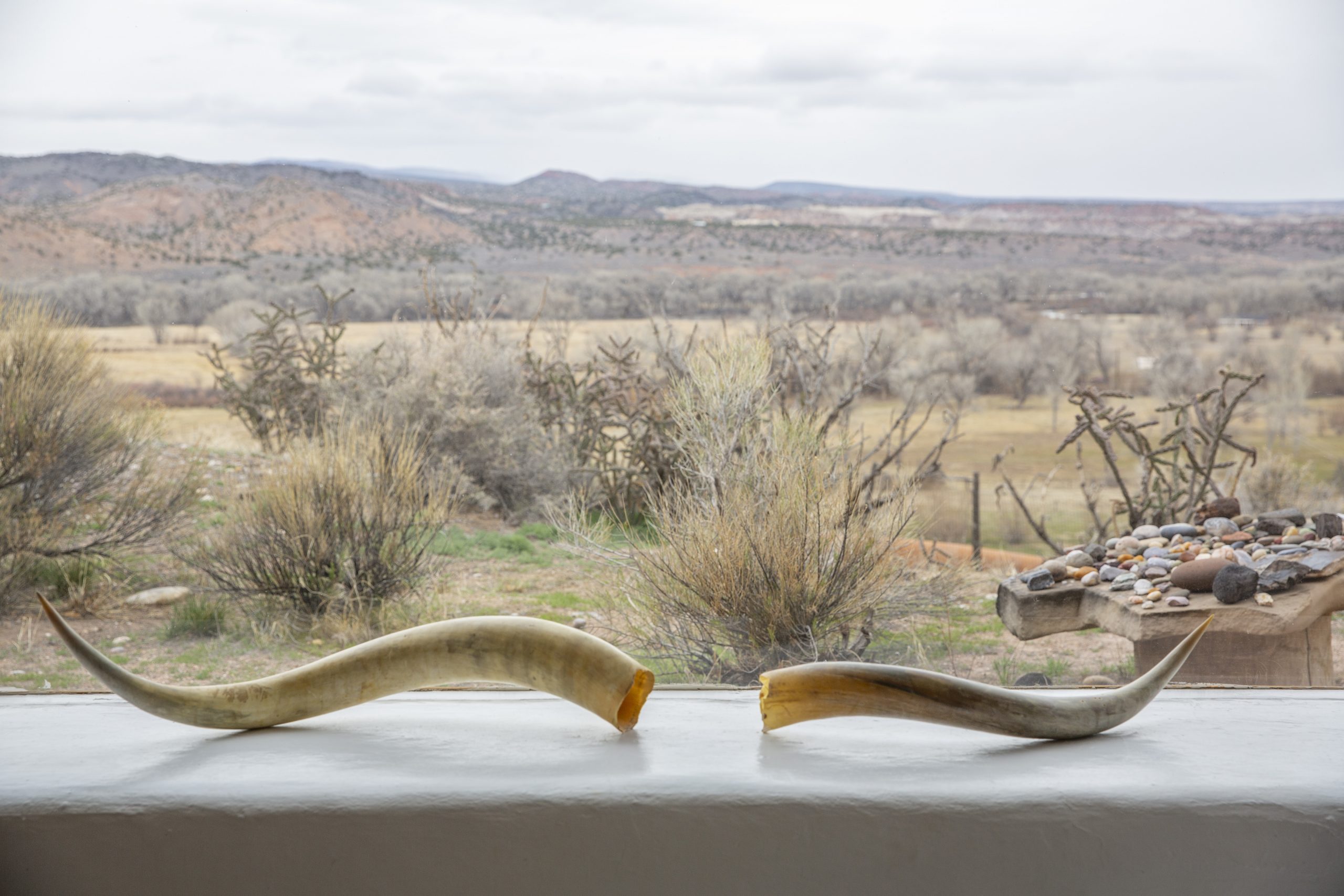

Abiquiú Sitting Room, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

Abiquiú Sitting Room, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

What has changed in the last four decades is that O’Keeffe is now largely synonymous with New Mexico, and every year, more than 12,000 people make the pilgrimage to that 5,000-square-foot hacienda and studio to study the traditional adobe architecture, stroll through her gorgeous gardens, and take in the midcentury-modern décor. To get an even better understanding of how O’Keeffe lived, Giustina Renzoni, curator of historic properties at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, says it’s helpful to get a sense of how the artist’s work, travels, and love for the landscape influenced her design choices.

Unknown. Georgia O'Keeffe, 1940 – 1960. Gelatin silver print, 8¹³⁄₁₆ x 7³⁄₁₆ inches. Georgia O'Keeffe Museum. Museum Purchase. [2014.3.93]

Unknown. Georgia O'Keeffe, 1940 – 1960. Gelatin silver print, 8¹³⁄₁₆ x 7³⁄₁₆ inches. Georgia O'Keeffe Museum. Museum Purchase. [2014.3.93]

Many artists — especially if they’re female — have to suffer through a miserable life and die before their work gets any respect from the establishment. Georgia O’Keeffe was not one of them. “She was really a rare example of a woman artist who was successful within her lifetime,” Renzoni says. While the $44 million sale of Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1 happened almost 30 years after her death (incidentally, the sale remains the highest ever achieved for a painting by a female artist at auction), Renzoni notes that O’Keeffe’s reputation as a well-respected modernist dates all the way back to the 1940s. “Her pieces sold for a quite a lot of money during her lifetime through her husband Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery, so she was very well-known and independently wealthy,” she says.

Abiquiú Garden, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

Abiquiú Garden, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

Part of what allowed O’Keeffe to become so successful was her willingness to stay open to new experiences, something that differentiated her from many of her contemporaries. “She didn’t conform to society’s standards — she was always a risk-taker, and she was willing to push the boundaries of what it meant to be a woman at that time,” Renzoni says. “She was very aware of her gender, but she didn’t want that to be her defining characteristic. She wanted to be considered an equal as an artist.”

That openness extended especially to her travels. “She liked living adventurously, and she was okay with roughing it,” the museum curator explains. Born in a farmhouse to dairy farmers in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, in 1887, she eventually moved with her family to Virginia, then took art classes in Chicago, New York, and Virginia, striking out on her art career by teaching art in South Carolina and West Texas, where she was inspired by the beauty of Palo Duro Canyon.

Abiquiú Studio, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

Abiquiú Studio, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

O’Keeffe liked to camp in rural parts of West Texas and New Mexico and went white water rafting on the Colorado River for the very first time at age 74 — she loved it so much that she went 10 more times. “Once international travel became more accessible in the 1950s, she began taking incredible trips to places like Thailand, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Egypt,” Renzoni says. “Unlimited curiosity is so critical to artists’ points of view, and she was looking for cultural experiences. It’s something I really admire about her — her willingness to subject herself to discomfort in order to deepen her relationship with nature.”

When she wasn’t touring the Far East or painting at her New York City studio, O’Keeffe headed west. She was introduced to New Mexico by way of Taos and spent a few summers with friends and fellow creatives like Rebecca Salsbury James and D. H. Lawrence in the 1930s,” Renzoni says. “There was already a real trend of artists coming to Taos then, and when O’Keeffe arrived, she initially stayed within a group setting.”

Abiquiú Roofless Room, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

Abiquiú Roofless Room, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

But O’Keeffe was notoriously private, so she had little interest in joining an artist’s colony long term. Instead, she was drawn to towns like Alcalde and Abiquiú. “When she went out into the desert there, she immediately experienced a solitude that’s impossible to find in an urban setting,” Renzoni says. The need to access the landscape alone actually inspired O’Keeffe to learn how to drive. She even purchased a totally customized Model A Ford that she drove from New York to New Mexico for her creative retreats. “The passenger seat could be removed to make room for a table, and the driver’s-side seat swiveled so she could paint on a canvas. She essentially created a mobile studio,” Renzoni says. “O’Keeffe preferred plein air and in situ painting, so she just got in the car, drove through the arroyos out to the desert, and painted anywhere she liked.”

[Right] Ghost Ranch Breakfast Nook, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. ©Georgia O'KeeffeMuseum.

[Left] Abiquiú Dining Room, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

In 1916 she had met influential photographer and gallery owner Alfred Stieglitz in New York. He had an eye and affinity for modernist talent and had come upon some charcoal drawings O’Keeffe had done. Without her knowledge or permission, he put on a show of her work at his famed 291 gallery. When she went to 291 to complain, fate changed course. She fell into romance first with modernist photographer Paul Strand and then with Stieglitz. She would become Stieglitz’s muse, the subject of countless black-and-white portraits and nudes, and eventually, his wife. In 1918, on his promise of a quiet studio where she could paint, she moved from Texas to New York. The two married in 1924 and would become one of the most storied — if complicated — unions in art history. Said Susan Stamberg in a story for NPR on the first volume of their collected letters: It was “a very modern marriage … with changes, variations, temptations, an infidelity and, of course, letters” which lasted until Stieglitz died in 1946. “Throughout, each groped for personal and professional fulfillment — and achieved so much.”

Abiquiú External, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

Abiquiú External, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

But it was in New Mexico that O’Keeffe would find the quiet she sought, and she journeyed there frequently. After Stieglitz’s death in 1946, she made the move to New Mexico permanent. She headed for her remote retreat — a cabin on a small parcel of land purchased from friends within the 21,000-acre Ghost Ranch, just outside of Abiquiú. The sublime surroundings inspired her work in a very literal way: paintings produced there include My Front Yard, My Backyard, and The Place I Live In.

Renzoni says the specificity of the names is hardly surprising to anyone who visits the area. “To outsiders, it’s hard to put your finger on what exactly it is about this area that makes it so special. There’s something so fantastical about the landscape — it’s very diverse geologically. There are bright white canyons, and up the road, there’s a gigantic red canyon,” she says. “And the sky is so expansive here — it’s also bluer.”

Ghost Ranch Studio, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

Ghost Ranch Studio, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

O’Keeffe later purchased a “winter home” a mere 13 miles away in the heart of Abiquiú. Why would she buy two homes so close together? Despite the proximity, “they’re in two totally different environments,” Renzoni says. “The Abiquiú home has a whole different landscape — a lush valley where she could have a lush garden with lots of fruit trees and flowers. She also had neighbors there, so it was a more social place, as opposed to her Ghost Ranch home, which is really remote with sandy soil, less water, and less green.”

Ghost Ranch Bedroom, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

Ghost Ranch Bedroom, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

However, turning the winter property into a home and studio fit for company was no easy task. Prior to purchasing the circa-1750s adobe structure, O’Keeffe had spent 10 years trying to persuade the Catholic Church to sell. When they finally relented, the place was in ruins. Undeterred, the artist brought in foreman — make that forewoman — Maria Chabot to oversee the complete renovation. “It was very unusual to have a woman in that role, but Maria was confident, fluent in Spanish, and very capable of working with the building community and artisans who were experts in adobe construction” Renzoni says. The latter skill proved incredibly important — while the team worked within the original footprint and added “amenities” like indoor plumbing, they also ended up having to craft more than 22,000 adobe bricks to reconstruct it.

Ghost Ranch Studio, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

Ghost Ranch Studio, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

Once the renovation was complete in 1949, O’Keeffe moved in and began making her mark on the light-filled interiors with a mix of modern furnishings and natural elements. “Everyone who visits is always blown away by how deliberate the design is, starting with the color ranges of the adobe. Each room has its own visual character, different ceiling types, and wall treatments,” Renzoni says. “She embraced the idea of finding beauty in every single part of her home, and she continued to design it throughout her life, changing the décor and furnishings. She really liked to think of her homes as her work as well.”

Even as the design scheme evolved, O’Keeffe always made room for her impressive library, which was filled with beloved novels and dog-eared nonfiction that covered a host of topics including gardening, cooking, and chow chows (her breed of choice). She also loved music and had top-of-the-line speakers installed in her studio and sitting areas. “She loved nothing more than heading to a sitting room at the end of the day, lying in a lounge chair, and listening to classical music,” Renzoni says.

Ghost Ranch Dining Room, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

Ghost Ranch Dining Room, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

When it came to accessories, O’Keeffe preferred carving out space for the rocks, skulls, and bones she unearthed on her daily walks over a more traditional art collection. “She was fond of a blank wall and rarely displayed the artwork of other artists in her home. She worried that it could interfere with her own work,” Renzoni explains. Still, she made room for select items, including a landscape by Arthur Dove, a mobile by Alexander Calder, and folk art and ceramics purchased on her travels.

As the artist’s health started to worsen — she began losing her eyesight at age 84 and eventually moved in frail health to Santa Fe, where she would die of natural causes just short of the century mark — she began to consider turning her home into a museum. O’Keeffe opted not to bequeath her home to the National Park Service. But she was okay with the idea that her home could be opened to the public as long as no major changes were made to the property. (Ghost Ranch is now operated by the Presbyterian Church and available for workshops and visits. O’Keeffe’s home at Ghost Ranch is not open to the public.)

Ghost Ranch Studio, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

Ghost Ranch Studio, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. ©Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

“The [Georgia O’Keeffe] Foundation was established after her death in 1989, and the home opened to the public in the early 1990s with the expectation that, maybe we’d do tours for five years or so, and then everyone who had an interest would have seen it. The foundation no longer exists, and the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum now maintains both of O’Keeffe’s homes. Here we are today, and the demand has shown no signs of slowing down,” says Renzoni. Still, the curator emphasizes that touring the home is only part of the Georgia O’Keeffe experience. “A sense of place was so important to her. I always encourage visitors to not just tour the Home & Studio. Get out in the landscape on a hike or picnic; visit some local stores; eat the food. She would really want you to get the full picture.”

Experience O’Keeffe

At Georgia O’Keeffe’s two places in Northern New Mexico, you can get to know the trailblazing artist, her art, and her sense of place through activities, tours, and exhibits.

There’s a lot to do in the area that inspired O’Keeffe. At the remote Ghost Ranch, there’s everything from trail rides and guided landscape strolls to movie, museum, and morning-stretch tours to hikes on five different trails and waterfront activities. While you must purchase tickets in advance for guided tour of the artist’s Abiquiú Home & Studio, you can enjoy an abundance of offerings at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Welcome Center, which is free and open to the public. There, you can check out an array of artwork, clothing, personal belongings, home furnishings, as well as the current exhibition, Around the World With O’Keeffe, which runs through March 24, 2024. Curator of historic properties Giustina Renzoni says the inspiration for the showcase began with the discovery of graphic matchboxes that O’Keeffe held onto after a flight on Japan Airlines. “Once I started looking around, I realized how much she had collected on her travels,” Renzoni says. “She visited 49 countries on almost every continent, and it impacted her work, as well as her sense of fashion and home designs.”

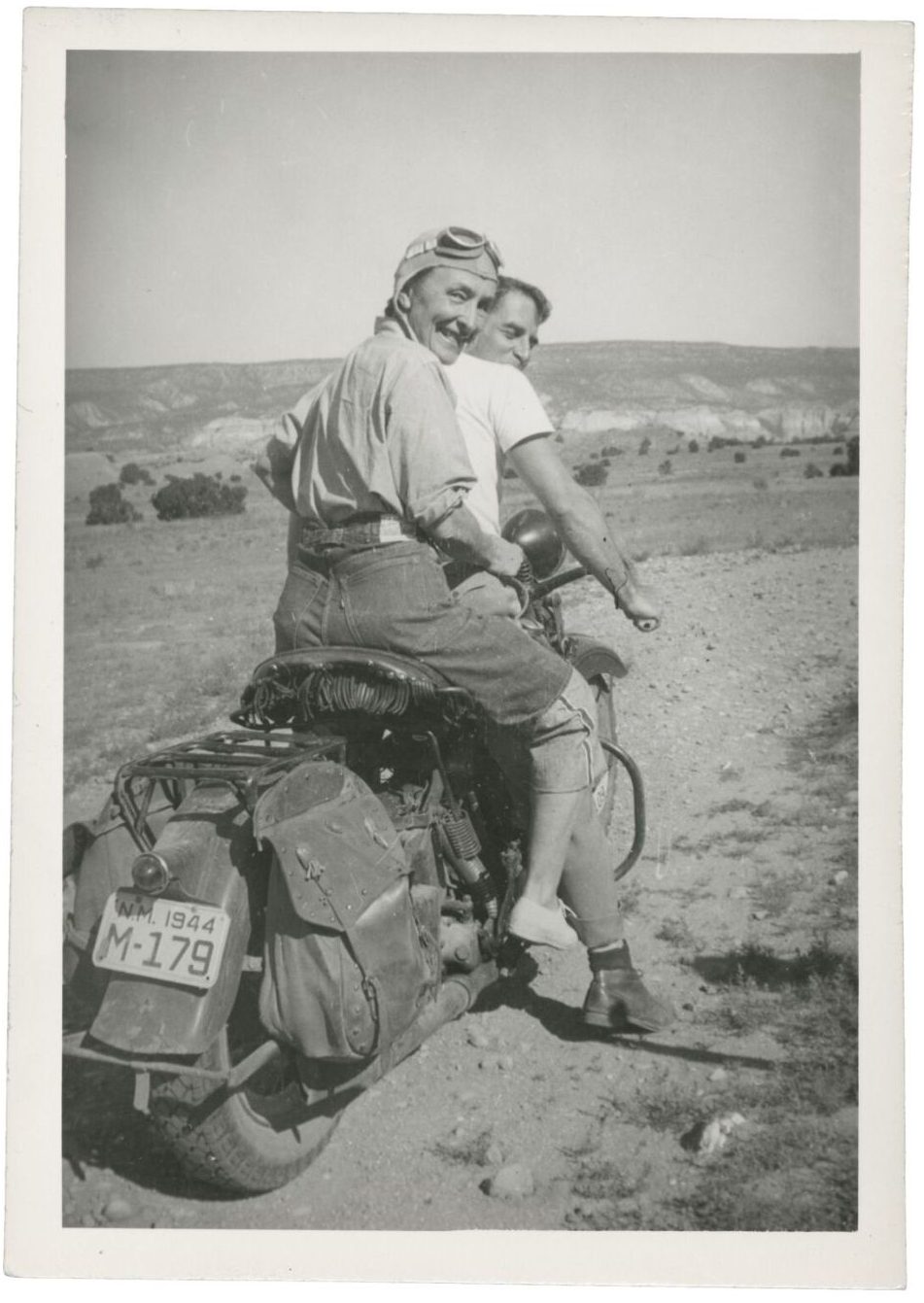

Maria Chabot. Georgia O’Keeffe Hitching a Ride to Abiquiú with Maurice Grosser, 1944. Gelatin silver print. Maria Chabot Archive. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Gift of Maria Chabot. ©Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. [RC.2001.2.140c]

Maria Chabot. Georgia O’Keeffe Hitching a Ride to Abiquiú with Maurice Grosser, 1944. Gelatin silver print. Maria Chabot Archive. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Gift of Maria Chabot. ©Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. [RC.2001.2.140c]

The curated collection includes a wide range of objects including more classic airline keepsakes, tourist pamphlets, action-packed itineraries, cooking ingredients, stylish clothing, meaningful mementos, and more. “It’s phenomenal looking at her itineraries and seeing how much she was doing,” Renzoni says. “She was jetting off to faraway places like Peru, Fiji, and Japan. I like imagining her going to places where she didn’t speak the language and doing everything she could while she was there.”

— L.K.

Find out about getting a day pass for activities at Ghost Ranch at ghostranch.org. For more information about the exhibit and to book tickets for Home & Studio, visit the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum website.

This article appears in our October 2023 issue, available on newsstands or through our C&I Shop.