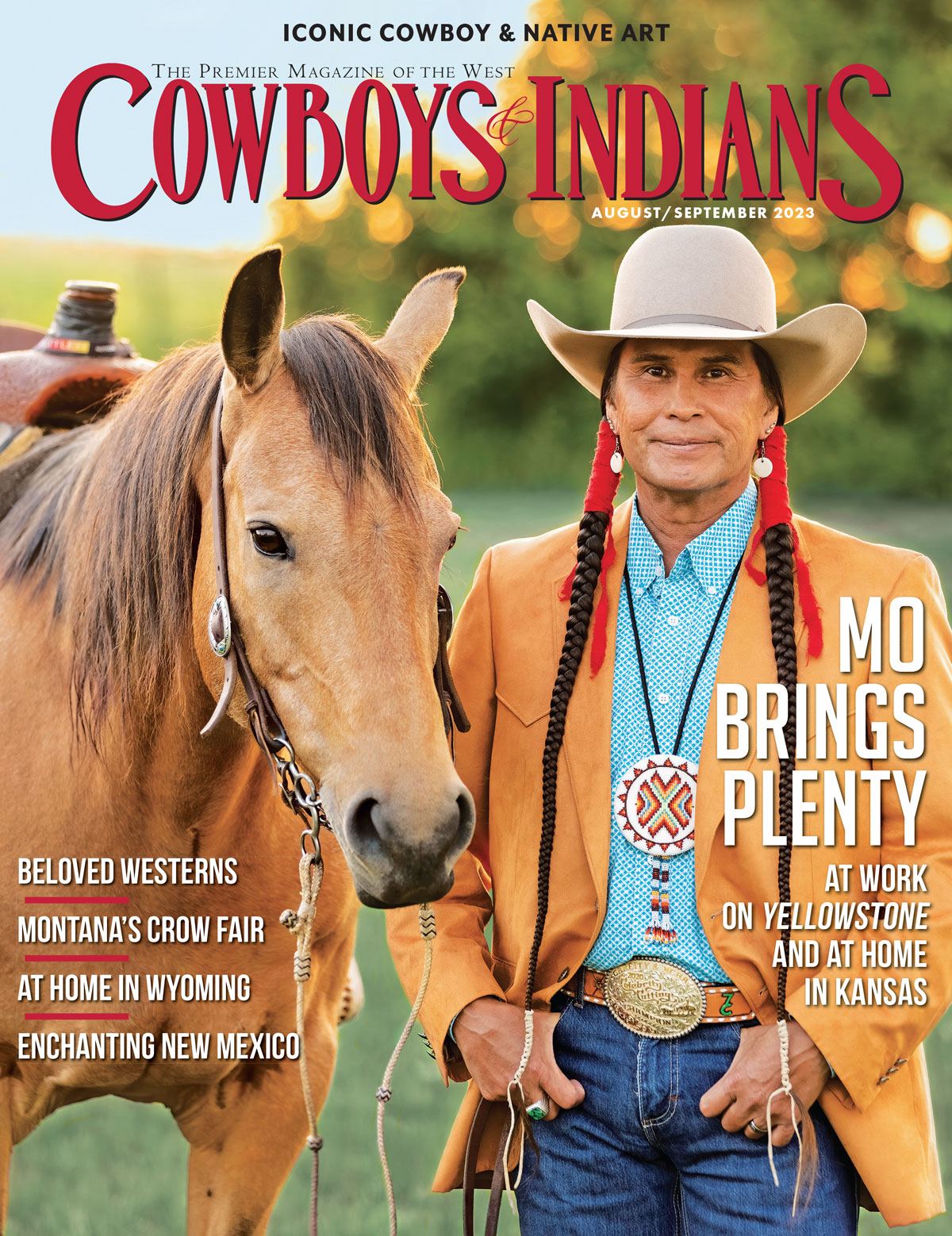

From an abusive boarding school to standing alongside Taylor Sheridan on the set of Yellowstone, Native actor and activist Mo Brings Plenty clues us in to where his insatiable love and compassion comes from.

Dusky twilight slowly gives way to the blackness of night as we're preparing to begin a sacred ceremony in the sweat lodge that Mo Brings Plenty has meticulously built on his family ranch in rural Kansas. Nature comes alive in the darkness that surrounds us, with coyotes layering their cheerful yips onto the sounds of the crackling fire nearby. He explains that he and his wife, Sara Ann, feed the pack through the winter to ensure their survival. Someone asks if the coyotes disturb the array of animals on the property: both domesticated and wild horses, cattle, buffalo, dogs, cats, and a hodgepodge of rescued ducks, geese, and other birds. In his characteristic gracious manner, Mo responds that his family lives in harmony with the coyotes, which are so often considered pests and predators.

This seemingly inconsequential conversation perfectly embodies Mo's life mission: to usher in a renaissance of coexistence among all human beings, animals, and Mother Nature. Most recognizable these days for his role in the blockbuster modern western Yellowstone, the 53-year-old actor has been pursuing that goal all his life, though he couldn't articulate it early on. In fact, he spent much of his younger years at odds with his Lakota identity — at once embracing the rich cultural heritage passed down by his ancestors yet feeling the deep shame that has plagued Native communities for centuries due to pervasive colonialism and forced assimilation.

My goal is to bring forth our cultural identity in this modern day but still keep our sacred truths and ceremonies protected. I hope to see more productions be fearless in incorporating American Indian people into their stories. Taylor Sheridan says it best: "You cannot tell a story of this country without including American Indians. ~ Mo Brings Plenty

Seeing Mo today — standing tall in his power as the American Indian affairs coordinator of Taylor Sheridan's ever-growing universe and as one of the most renowned Native actors alongside the likes of costar Gil Birmingham, Kimberly Norris Guerrero, Zahn McClarnon, Will Sampson, Wes Studi, and more — it's hard to imagine a time when he didn't fully embrace who he is. But he confides: "One day I went to my father and told him, 'When I grow up, I'm going to move away, change my name, and cut my hair off. And if I could change the color of my skin, I would, because my we're taught to be ashamed of what God created us to be.' That's what society teaches us, and I really struggled with that."

In those moments of inner conflict, his cultural traditions helped keep Mo grounded. "But then I'd get refilled with life, especially in the summertime when ceremonies were going on," he says. "It all boiled down to remembering the sacrifices that our ancestors made for us. Whenever I found myself at a crossroads, I would always pick the right path that helped me understand more and more who I am."

And just who is Mo Bring Plenty? He is an Indian, a cowboy, a rancher, an actor, an activist, a musician, a family man, and an animal lover. He is a descendant of Brings Plenty on his father's side and Makes Room on his mother's side, two Lakota warriors who fought at the Battle of Little Bighorn, with direct connections to Sitting Bull. In so many ways, he represents the confluence of traditional and progressive values seen across Indian Country — his surname reflecting his tribal lineage and his first name, Moses, reflecting Christian influences.

Mo came of age in the '70s and '80s across South Dakota's Lakota Nation — at his birthplace of Pine Ridge as well as on his mother's Cheyenne River Reservation and his relatives' Rosebud Reservation — without electricity or running water. "Those were the best days of my life," he recalls. "My childhood was filled with great teachers and a lot of culture and tradition. We had to work for everything. My brothers and I would haul water and cut and gather wood with my dad. Our imaginations were endless. We would literally sleep under the stars. For us, punishment was staying inside, because we always wanted to be outside."

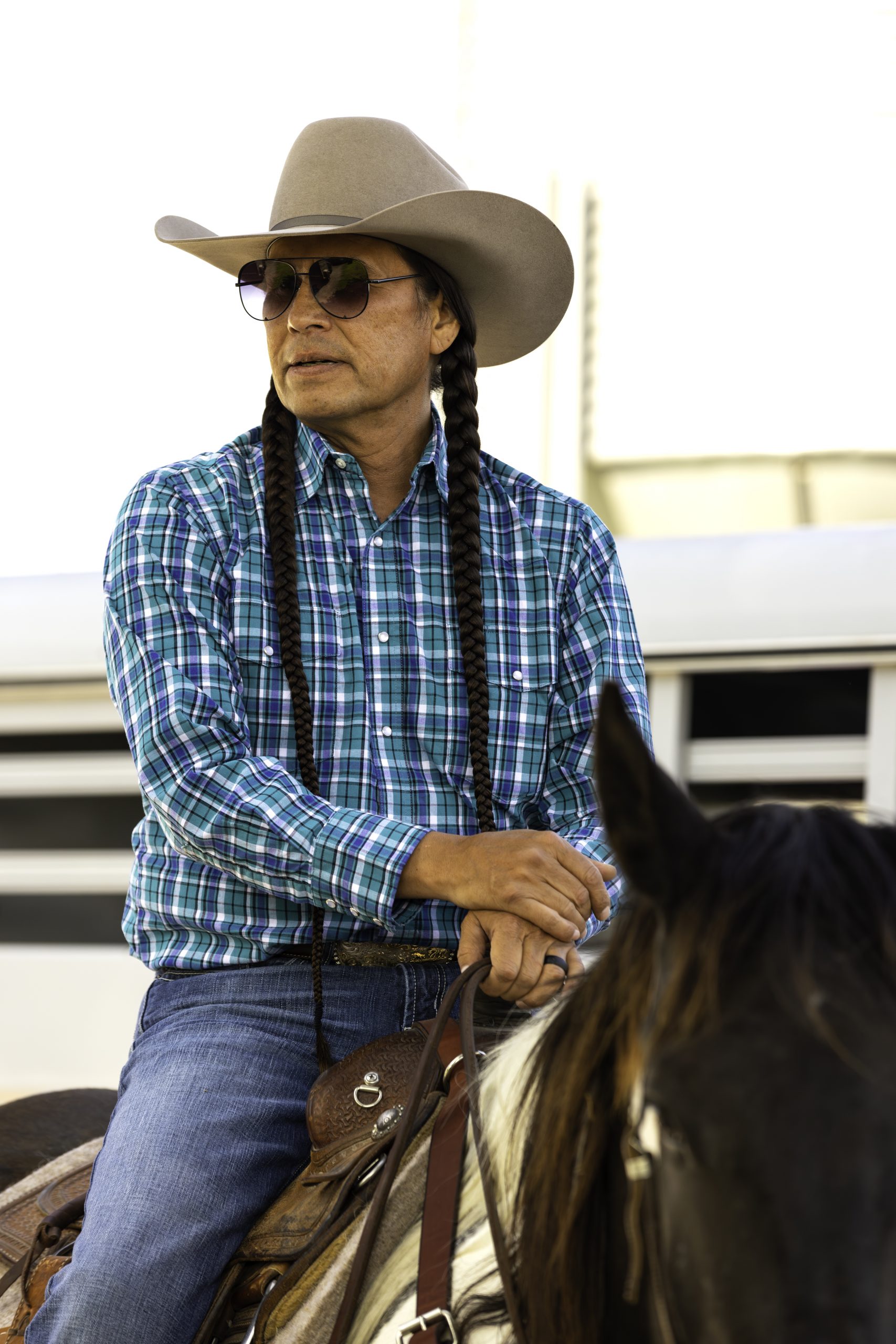

True to his traditional name — Ta Sunke Wospapi, meaning "catches his horse" in Lakota — Mo has spent his entire life around horses, growing up riding bareback and eventually testing his mettle at rodeoing. "I had a lot of heart, but no talent," he says with a laugh. "But there was this brotherhood among the athletes, even though we were competing against each other. It was one of the first places where I didn't feel judged for my race, my faith, or my political views."

After more than a decade trying to make it riding bulls (and sustaining plenty of injuries), he called it quits at 28. "But I can still ride horses like there's no tomorrow," Mo says. "I can honestly say that horses saved my life. If it weren't for them, I don't know who I'd be today. I wouldn't know what humility is. I wouldn't know how to stand up in a strong way that's still respectful to others."

That profound connection with horses is one that runs deep not only within Mo's blood but within larger Native history. "Our horse culture was vibrant long before the Spanish brought their horses here," he notes. "As Lakota people, we have songs and ceremonies that are specifically for the horse. Just like American Indians, they've always been here." Indeed, recent research confirms that Natives' longstanding partnerships with horses predate European contact by a long shot.

Horses are such beautiful medicine. I can still ride horses like there's no tomorrow. I can honestly say that horses saved my life. If it weren't for them, I don't know who I'd be today. I wouldn't know what humanity is. I wouldn't have known how to stand up in a strong way that's still respectful to others.

But all of the joy of Mo's upbringing is interlaced with trauma, like experiencing abuse at the hands of a Catholic priest at Red Cloud Indian School, a Jesuit-run former boarding school that's still in operation today. He tried to escape "a world that didn't want his kind" by attempting to take his own life as a teenager. Mo recalls the visceral memory: When he was 16, he stuck a gun barrel in his mouth and pulled the trigger, but nothing happened. His dad came in to find him and discovered that although the firing pin had hit the bullet, the gun hadn't gone off — a miracle to be sure.

Tribal leaders like Selo Black Crow, Leonard Crow Dog, and Roy Stone, along with his parents, aunties, and grandmothers convinced Mo he had a greater purpose in life. That translated into the slow start of his acting career, spurred on by the 1990 film Dances With Wolves.

"When you look back at the old westerns, American Indians were always portrayed as the villains," he says. "But Dances With Wolves showed the truth of who we are: compassionate, loving, and understanding. That production made me strong in who I was again." Even all those years ago, Mo recognized the part he could play in bringing about more authentic Native representation in media — and the incredible impact that could have on rez kids like him.

So at 32, he packed up his belongings and moved to Nebraska to pursue acting at the Omaha Community Playhouse, where Marlon Brando and Henry Fonda made their debuts. That theater work eventually led to stunt work on films like The Revenant, which eventually led to supporting roles in television hits like Hell on Wheels and House of Cards. Although he relished portraying notable figures like Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull, Mo remained disappointed by Native characterizations and felt insulted by ignorant requests to compromise his Lakota identity, like wanting him to cut his trademark long braids. He contemplated stepping away from it all.

Around that same time, his friend Frank Kuntz invited him up to North Dakota to witness the magnificence of the Nokota horse — believed to have descended from Sitting Bull's horses — which Kuntz and his brother have been preserving since the wild breed was driven out of Theodore Roosevelt National Park in the '90s. To Mo's surprise, Frank gave him a young roan gelding, now known as Roany. The first time Mo sat on his back, the experience filled the nagging void he'd been feeling.

"In that moment, it dawned on me that this horse's grandparents carried my grandparents," he says. "We were separated, but here we are, back together. Horses are such beautiful medicine. The Nokota horses in particular are very important because they still have a great knowledge that we no longer have today as a people. But if we rebuild that relationship, they will share with us again that great knowledge that we need."

Call it fate, serendipity, divine intervention, whatever you will — but shortly after having this epiphany, Mo landed the job on Yellowstone. What began as a smaller acting role as the driver for Thomas Rainwater (Gil Birmingham) blossomed into one of the series' most beloved characters and expanded into a position as American Indian affairs coordinator across Taylor Sheridan's entire universe. He'll appear in Sheridan's forthcoming Lawmen: Bass Reeves as Minco Dodge, a Choctaw who is friends with David Oyelowo's title character, the first Black deputy U.S. marshal west of the Mississippi. And Mo brings his full self — the good, the bad, the everything — to his work.

"Every ounce of fear, anger, frustration, and even joy from my past goes into my acting, so that I never forget where I came from," he explains. "Even as coordinator, I need to be able to express that emotion. I was forced to eat soap as a kid. I was yanked around by my hair. I was hit with rulers. I was told by my school counselor that I would get nowhere in life because I was Indian. But thanks to Taylor Sheridan, I proved them wrong."

In his work as coordinator, Mo ensures all aspects of Native culture showcased — from regalia to language to ceremonies — are accurately depicted. He taps knowledge keepers from the specific tribes represented to help guide the cast and crew on set. For 1923 breakout star Aminah Nieves' speaking scenes, for instance, that involved learning the Crow language from tribal elder Birdie Real Bird.

"I am simply the bridge," Mo demurs. "I myself am still a student, and just witnessing these elders' knowledge is so inspirational. They have sacrificed so much to keep these traditions alive, and now they are finally getting the respect they deserve, not just in their own communities but worldwide. I hope this sparks a hunger for more knowledge within our young people so they learn about their culture while these elders are still here."

It's that younger Native generation, whether on the reservation or in suburbia, that Mo is aiming to reach. "If I fail at my job, then I've failed our people and our ancestors," he says. "My goal is to bring forth our cultural identity in this modern day but still keep our sacred truths and ceremonies protected. I hope to see more productions be fearless in incorporating American Indian people into their stories Taylor says it best: 'You cannot tell a story of this country without including American Indians.'"

Showcasing the rich diversity of the many tribes across Turtle Island is of the utmost importance to help dispel the myth that Native culture is a monolith. "So many people imagine us still in leathers and feathers and think we all live in tepees and go to powwows," he says. "But in Indian Country, we don't all share the same culture and speak the same language. These are certain values that are universal, but we are very diverse."

Bearing witness to traumatic scenes, like 1923's hyperreal reenactments of boarding school horrors, brings up a plethora of emotions for Mo, who is always on set for the filming of Native plotlines so he can ensure accuracy and a safe environment. "There have been some very emotional scenes where I have had to walk away from the monitor to have a moment by myself," he admits. "I'm not going to lie — I've cried because it feels so real. But thanks to our amazing cast and crew, we're able to come back and understand we are all safe together."

He also helps younger actors understand the significance of their roles. "For 1923, we id a casting call on the Flathead Reservation and got a bunch of kids who probably never thought they would ever be part of a television show," Mo says. "The first day of shooting, I told them, 'If we want people to know about us, we must know ourselves first. If we want people to respect us, we must respect ourselves first. But understand that we are not then — we are now. And we are still here.' Because what better way to make a statement to the world that, although we have been through a lot, we are still strong in our identity in our culture, in our language?"

Acting alongside Kevin Costner, who directed, produced, and starred in Dances With Wolves, has been a full-circle experience for Mo. "He introduced who American Indians really are to the world, and the world accepted us," he says. "But even though that production won so many awards, there was a huge gap after Dances With Wolves because no one wanted to tap into who we are — until Taylor Sheridan."

Mo is encouraged by the honest Native representations we're seeing in pop culture today, pointing to Sterlin Harjo and Taika Waititi's groundbreaking Reservation Dogs — the first series to feature all Native directors and writers and an almost entirely Native cast and crew. Like Yellowstone and its prequels, Reservation Dogs doesn't shy away from showing the real issues tribal communities face: the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women crisis, the Indian boarding school atrocities, and high rates of poverty, disease, addiction, and suicide. These issues hit close to home for Mo, who has a relative who's been missing since the '80s.

For all his work in media, Mo's advocacy goes beyond the screen. Having experienced firsthand the life-changing influence of rodeo, he is a proud spokesperson for the Indian National Finals Rodeo and wants INFR athletes to be afforded the same opportunities and acclaim as those in the PRCA. He also serves on the board of the Bronc Riding Nation and as a consultant with Western lifestyle and entertainment company Teton Ridge. And Mo might even one day affect policy in America, having recently participated in a U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs panel alongside 1923 stars Michael Spears and Cole Brings Plenty, his nephew.

Despite his undeniable impact, Mo wants his legacy to be unknown to future generations. "I wonder how many of my own people know who Crazy Horse's parents and grandparents were," he muses. "So few of us know our ancestors beyond the heroes who made a stand during trying times. But we don't think about the people before them, because life was good then. So I hope people don't remember me, because that means life is finally good once again."

Which brings us back to the concept of coexistence, a seemingly lofty goal in today's highly divisive times. But to hear Mo explain it could convince even the most resistant skeptic. "I'm living proof that we can coexist," he says plainly. "I can coexist with anyone in any setting and remain true to who I am. We're all given an opportunity in this moment in life to find a way to coexist. We can't change the past, but what we do today can make tomorrow a better world for all people. At the end of each day, I reflect on what I've done and ask myself if my ancestors want to be in my presence as much as I want to be in their presence."

Mo Brings Plenty working at Teton Ridge’s TR9 Ranch alongside TEAM:TR athlete Corey Cushing, the first rider of the National Reined Cow Horse Association to surpass three-million-dollar in lifetime earnings.

When he finds himself in times of trouble, Mo returns to the traditional ceremonies that reconnect him with his ancestors. On this summer evening on his idyllic home ranch in Kansas, he is sharing a part of himself and his people, inviting a handful of friends to partake in inipi, a spiritual sweat lodge ceremony of rebirth, rejuvenation, and reawakening. In doing so, Mo is educating Natives and non-Natives alike — something he does skillfully and selflessly. He's also reminding himself who he is — someone he once hated but has come to love. And he's leading a life that will no doubt make his ancestors proud to someday stand beside him.

Photography by Eugene Tapahe

TR9 Photography by Tim O'Keefe

This article appears in our August/September 2023 issue, available on newsstands or through our C&I Shop.