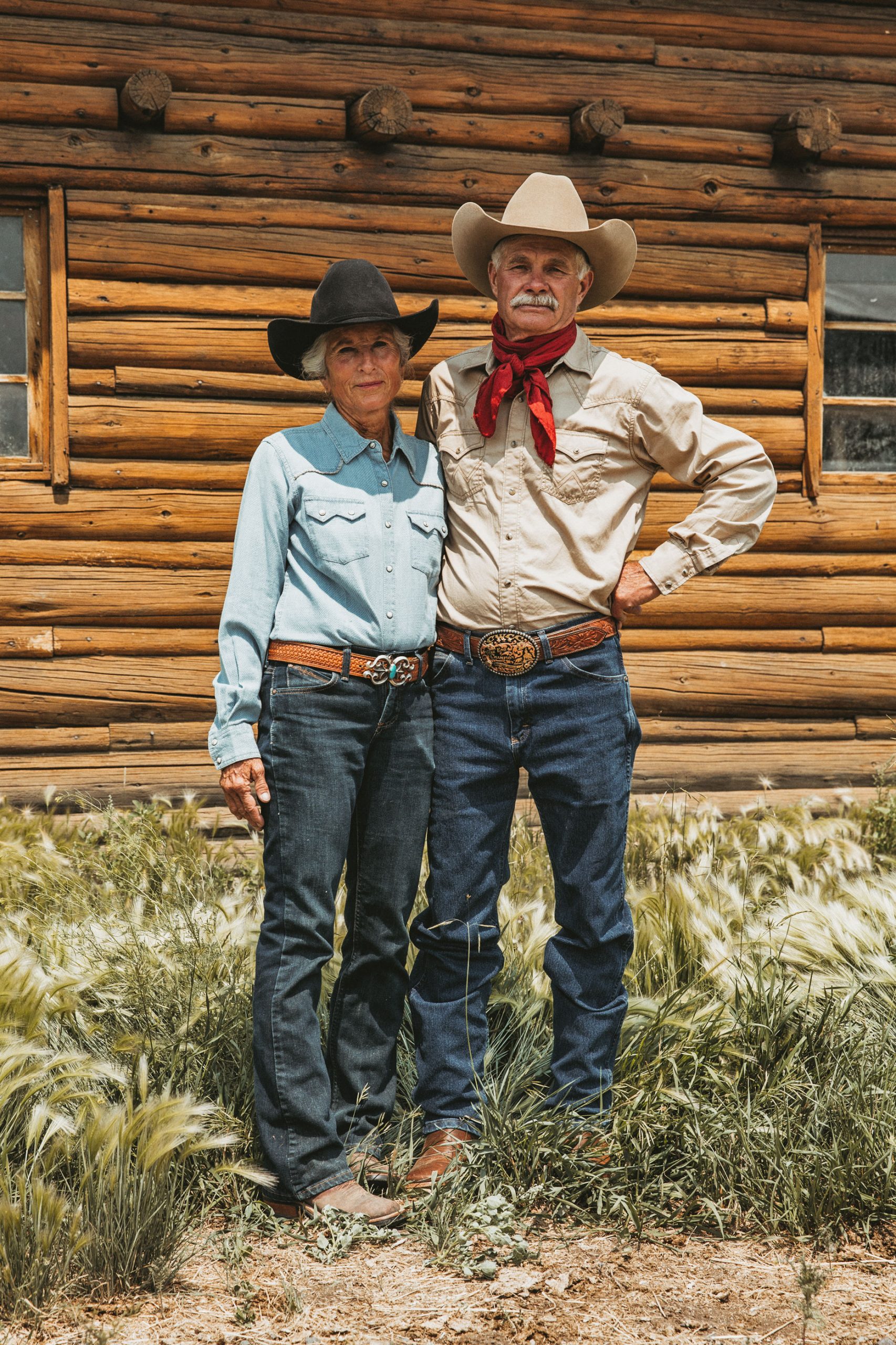

Holding on to heritage in one of the most competitive Rocky Mountain real estate markets is no small feat. But the Diamond Cross has made it work over four generations. Today, Jane Golliher, her husband, Grant, and their children host guests from around the globe on what started as a humble homestead.

Humble Beginnings

Anyone who made it homesteading in Jackson Hole had to be determined. The first settlers here were about as rugged as the jutting mountains and rocky soil they staked their lives on. My grandparents, Frederick and Caroline Feuz, were among them.

Fred and Caroline left Switzerland to join relatives who had immigrated to Utah. From there they headed to Driggs, Idaho. Struck by the Tetons’ resemblance to the Alps, my grandfather came over the mountain in 1912. It would be another two years before the town of Jackson was formally incorporated, but most homestead plots had been bought up. Instead, my grandparents moved on 25 miles north to Spread Creek, a seasonal tributary to the Snake River near the base of the Tetons, in Buffalo Valley.

They built a two-bedroom cabin while my grandmother was pregnant with their third child, through the summer months into the fall. The house wasn’t completed when the first winter storms blew in, but the young family toughed it out.

Because of a short growing season and harsh winters, this was a difficult place to make a living. My grandmother diligently tended her gardens and mostly grew potatoes. My grandfather guided elk hunters. They had some cattle, which eventually became the focus for my father, Walter.

Fred and Caroline ended up with 10 children. Dad said they seldom wore shoes in summer because they had to save them for winter. Most of them never went into town until they were about 13 years old. But a small schoolhouse in the community of Elk, Wyoming (today, Moran), provided homesteader kids with a good education. The children walked to school, took a team of horses, or pulled each other on sleds. My grandparents were farsighted. When the kids reached 8th grade, they sent the girls to Driggs to live with relatives so they could attend high school. They felt the girls needed a profession. The boys could use their land skills to make their way.

My father was a good bronc rider and traveled around Wyoming competing. He enlisted in the military during WWII and ended up stationed in California, where he competed in the World’s Rodeo. Shortly before the war, Dad started ranching with his brother, Emil. When he returned, he bought the whole outfit.

My mother, Betty, came from Chicago. Her mother vowed to never speak to her again if she didn’t marry a suitor from Texas. So, she married him but quickly got it annulled. She reconnected with a childhood friend, Esther, who had married one of the Craighead brothers, famous naturalists who studied grizzly bears in Yellowstone. Mom used her father’s railroad job to reach the train station in Rock Springs, Wyoming. She worked at the Moose Post Office. Esther and her sister-in-law lived nearby, three miles as the crow flies. They cross-country skied to one another’s houses, which we also did as kids.

Mom met Dad at a barn dance. They married soon after. Even though she came from a middle-class suburban family, she fell into this wild pioneering adventure. They had no electricity, only a generator. The highway that runs in front of our property today was nonexistent. When I was a child, we’d drive our team from the house to the road, where we left the car parked for winter.

Rockefeller Comes Around

Starting in the 1920s (under the guise of Snake River Land Co. to ensure he got fair-market pricing), John D. Rockefeller, Jr. started purchasing ranches across the valley, which were later handed over to the federal government to create Grand Teton National Park.

My grandparents were approached about selling their homestead. But the Feuzes were determined. They didn’t sell. It wasn’t until decades later, after my grandfather died and my grandmother moved, that our family eventually traded the 160 acres in Spread Creek to Grand Teton National Park for 400 acres up the valley, which today is the Hatchet Ranch. It was a good trade — better ground and a lifetime lease to run cattle on the National Forest.

Not that long ago, ranchers ran their cattle together during the summers. When I was young, my first husband and I punched cows for the Hansens and the Porters. We ran all these Herefords up and down the Jackson Hole valley. I trailed cattle from Jackson, 35 miles to Moran. Dad didn’t get any cowboys; he got us four cowgirls. My sisters and I were respected because we were some of the few girls living out in the middle of nowhere and punching cows.

Jackson was a quiet cow town then. It was agriculture-friendly. But even before it shifted into more of a conservation and recreation scene, cattle was a tough way to make a living.

Soon after I first got married, I worked for Laurence Rockefeller on the JY Ranch. It’s where my boys were born. When I got divorced, I returned to Buffalo Valley. The ranch had gone on with my parents and sister. Eventually, Dad fell sick and Mom had to sell most of the herd. My sister and her husband took some cattle and kept their permit. It’s not enough for them to make a living, but they’ve held onto the ranching.

Diversifying Beyond Cattle

We joke that even if my parents hadn’t had health issues, the reality of Jackson Hole by then was that we were raising hundred-dollar cattle on million-dollar grass. Then there was the wolf reintroduction and the grizzly bear recovery. Conservation groups bought up remaining grazing permits. It got tougher for ranchers who were left to find open land. We saw the cowboy way of life going away.

As the land went up in value, Mom and Dad worked with an attorney to gift down the ranch to the family. When Dad passed away, they had the boundaries laid out as to who got which piece so that the ranch could still run continuously. That planning helped us diversify and hold on to the land.

Oddly enough, I met Grant through his first wife, who, in the 1970s, worked at the Heart Six guest ranch across the river. After he retired from playing polo in California, Grant too moved to Wyoming. Some 20 years later, both of us then divorced, he and I reconnected at church in Jackson. We married in 1997.

We stumbled into the hospitality industry — or more like, God directed us into it, though we couldn’t see it at the time. My parents always had a real sense of hospitality. If someone showed up hungry, it didn’t matter if the rest of us had eaten, Mom fed them. There was a wonderfulness about living with a hodge-podge of people. Some ranch hands were around only for a few weeks. But there was always a sense of family. We strive to treat each of our guests that way still today.

Grant and I started out with horseback rides and “Cowboy for a Day,” taking out dudes to help move cattle. We ran yearlings and were paid to put weight on them. But we also found we could use them for team penning and cutting, which opened new doors of opportunity. This was the first of our experiments with “creative agriculture” — finding new ways to make the ranch profitable. At the same time, we worked a lot of odds and ends to pay the bills — cleaning houses and shoveling roofs in the winter. Grant shod horses and put on clinics.

Over the years we’ve been directed by dreams and visions many times. God has often spoken to us this way. Many we have never shared, just tucked away to see how they unfold. That’s what led us into hosting events.

In the late ’90s, Grant had a dream about a big white tent out in our pasture. We didn’t make much of it until we were approached by Microsoft about putting on a private rodeo for their executives. We gave it a shot. Mostly winging it, we hosted the event for 300 of their top executives. On that one day, we made more money than we did all summer breaking and shoeing horses or leading rides. We bought the big white tent.

We had $5,030 in our savings account. The tent cost $5,000. We had to cut down our own poles to prop it up. In those early days, we put up a sandwich board on the side of the road, hoping passersby would stop in. We got by on prayers, tips, and God’s grace.

But it wasn’t long until Grant’s horse-whispering demonstrations and cowboy poetry began to draw in groups from Jackson Hole’s big resorts. In the first five years, we hosted Sandra Day O’Connor, members of Congress, the Young Presidents’ Organization, and the American Bar Association.

The tent wore out. We sold 20 acres and built a 13,500-square-foot barn with full-window views of the Tetons. We moved the horse-whispering demonstration into the barn to beat the elements. We’d always been land-rich and cash-poor. The land sale also helped us put the two boys through Ivy League schools. Luke was the first student to graduate from Jackson public school to go to Harvard. Peter went to the University of Pennsylvania. Now they’re using their educations to rethink how we do things. We’re so grateful they didn’t just take off.

Over the years, our circle of influence has grown. We’ve hosted Fortune 500 leaders, heads of state, and foreign dignitaries. We still couldn’t tell you which dining utensil is the salad fork and which is the soup spoon. But we’ve wrangled cattle with the Kardashians and broken bread with two U.S. vice presidents. We’ve been on billboards even while we’re digging out our ditches.

Grant’s demonstration is like a parable. People are drawn into it. They see the horse, feel its fear. They watch the transformation and relate that to themselves. We’ve found the message resonates most with people who have little or no horse experience. What Grant teaches is about much more than breaking a horse — it's lessons for relationships, careers, marriages, children. People from all walks of life can draw parallels between his work with a horse and their own lives.

The Future of Diamond Cross

We feel what God has given us is a three-legged chair. First, the unobstructed view of the Tetons, a 360-degree view without sign of human habitation. Second, a building to host groups and events on a scale we never dreamed of before. And, finally, Grant’s message through horses, which has touched leaders from across the globe.

It’s been quite a ride, and it owes mostly to the necessity of having to find new ways to do things when the old way doesn’t work anymore. We could sell out, but we don’t want to. Our kids want to continue to build on what was started over 100 years ago. And they want their children to be able to experience this remarkable way of life, too.

We’re only here for a short season. Each of us feels we’re stewards of the land, that our responsibility is to hand down the land and opportunities we inherited to the next generations. And not just that, but to share it with people from around the world, rather than gate it off.

We want to share our story for years to come, because if we don’t tell it, it dies.

The Next Generation

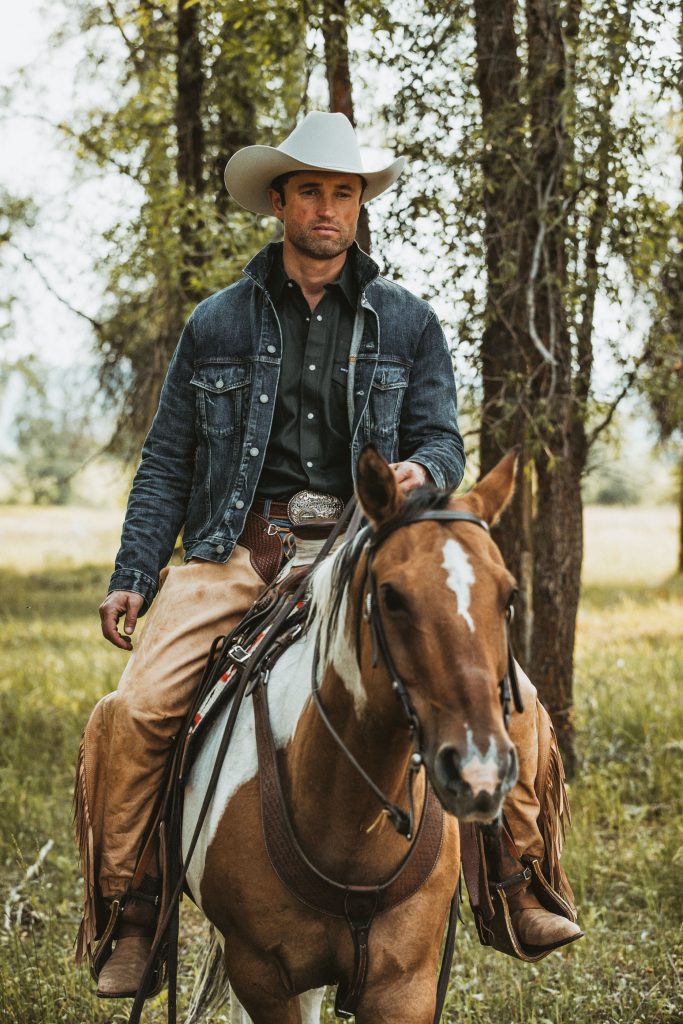

Heritage and legacy, family and the future — brothers Luke and Peter Long strive to preserve the Diamond Cross Ranch for the sake of authenticity and posterity.

Jackson is a one-way door: You can leave, but you can't return if you change your mind. It's a microcosm of the gentrification going on across the Rockies.

Not long ago, it was an eclectic cattle town with a ski hill. That appealed to people, along with the scenery. Now, drive through historically blue-collar areas and there are massive mountain modern homes. First, there was the loss of historic ranching families. Recently, there's been an attrition of outdoor enthusiasts. Many sold homes during the pandemic because they couldn't turn down sky-high offers. The community has been supplanted with the feel of one big destination resort. We're struggling with middle-class housing, healthcare, childcare.

Despite the challenges, we're optimistic. The pride in the land, all that was invested before us, has encouraged us to keep the ranch as open space. The goal is to pass it to our children. We get to do it as a family, with everyone offering skills. When we were boys, it felt like the rug was being ripped out from under us, as it did for a lot of ranchers. But now, with Grant's horsemanship demos and hosting destination weddings, it feels like we have a solid plan for the future.

Within each revenue stream is the heritage of the ranch — focused on the horses and making the ranching part of all those activities. We try to be true to that legacy. With everyone growing up on social media, kids will want to get back outdoors and experience riding a horse. People want things that are family-owned, to know where it comes from, what it stands for. The world is full of brands that are invented stories that are labeled "Western." Consumers want to know if the story is true.

We hear, "We love this because there's history. It's real." It's worked out well that we've come into a time in which authenticity is valued. We're keeping Western heritage alive, not selling out to condos, and because of that, we'll hopefully tell the Diamond Cross story for generations to come.

~ Luke and Peter Long

Diamond Cross Ranch was recognized as Jackson Hole’s Best Wedding Venue for the fourth year running, and their affiliate Teton Cabins were honored with second place in the Best Hotel category. To learn more about Diamond Cross, visit ranchjacksonhole.com.

This article appears in our July 2023 issue, available now on newsstands or through out C&I Shop.

Photography: Chris Douglas