The life of the exceptionally gifted and important Yankton Sioux writer, musician, and activist Zitkala-Ša proved a bicultural journey that would defy her times and gender.

It would stand to reason, given the deep-rooted bias against her race and her sex, that a Sioux Indian girl born into late-Victorian, predominantly white America might have little to no chance for growth and fame. Nonetheless, against all odds, the woman who called herself Zitkala-Ša grew to become a teacher, a widely read author, a concert violinist and classical composer, co-founder and president of the National Council of American Indians, and a world-recognized advocate and lobbyist for the rights of both women and Native Americans.

The year of Zitkala-Ša’s birth, 1876, was significant, representing as it did the 100-year anniversary of the founding of the United States. It also marked the Native Americans’ last great victory over the nation’s military, when the troops of Lt. Col. and presidential hopeful George Armstrong Custer were soundly defeated by a combined force of Sioux, Arapaho, and Northern Cheyenne warriors.

Gertrude Kasebier, 1898

Gertrude Kasebier, 1898

For the American Indians, it was the victory that heralded their imminent subjugation. Isolated instances aside, their resistance that had impeded Anglo-America’s expansive drive to the Pacific Ocean had been neutralized. It now became a time of forced assimilation, in which, under the mantle of “civilizing the savage,” tribal cultures were being systematically demolished. One way in which this was achieved was through the “reeducation” of Native American children in government-sponsored, Christian-run boarding schools.

This was the world that the child named Gertrude Simmons inherited. She was born on South Dakota’s Yankton Agency, to a Sioux mother and a white father. The Yanktonai had signed a treaty with the federal government in 1858, and although they had avoided the bloody resistance that had resulted in the subjection of other regional tribes, life on the reservation was harsh.

Gertrude’s father had earlier abandoned the family, leaving her traditional upbringing in the hands of her mother and the tribe. She learned beadwork at her mother’s knee and was weaned on the folktales and origin stories that would later appear in her books. “I was as free as the wind that blew my hair,” she later wrote, “and no less spirited than the bounding deer.”

When Gertrude was 8, Quaker missionaries came to the reservation seeking children to enroll in White’s Manual Labor Institute, their federally funded Indian boarding school in Wabash, Indiana. Such schools represented a national program to systematically remove children from their tribal environment, in order to assimilate them into white society. Some of Gertrude’s friends had already been given permission to go, and for the child, it was an easy sell. Gertrude begged her reluctant mother, who warned her, “Don't believe a word they say! Their words are sweet, but, my child, their deeds are bitter. You will cry for me, but they will not even soothe you.” She finally relented, and Gertrude boarded the train that would take her far from her mother, and farther still from her tribal identity.

The school, she later recalled, “bound my individuality like a mummy for burial.” As did nearly all the other Indian boarding schools, it ran on the principles and objectives of Richard Henry Pratt, a former military man who had founded the Carlisle Industrial Indian School in Pennsylvania five years earlier. Looked upon as the model for all such institutions, the Carlisle School operated on Pratt’s personal philosophy: “Kill the Indian, save the Man.” All traces of tribal influence were to be eradicated. Drawn from various tribes and thrown together, the students were forbidden to wear their native garb or speak in their own tongue, which was especially difficult for Gertrude, who spoke no English. They were prohibited from communicating with their families and from maintaining a belief in the Great Spirit.

Conversion to Christianity was mandatory, as was the cutting of the students’ hair. As she later wrote, “Our mothers had taught us that only unskilled warriors who were captured had their hair shingled by the enemy. Among our people, short hair was worn by mourners, and shingled hair by cowards!” Although Gertrude tried to hide under a bed, she was dragged out, tied to a chair, and forced to endure the shame of a shearing, her long, flowing hair cut close to the scalp at the nape of her neck.

Anonymous, 1898

Anonymous, 1898

The training that the uniformed children received was designed to prepare them for nothing beyond jobs as handymen, laborers, maids, and housekeepers. The treatment was harsh, and corporal punishment was a common recourse for slow or recalcitrant students. The mortality rate among Indian children in the schools was staggering, due to malnutrition, poor living conditions, disease, and often simply despair. “Not a soul reasoned quietly with me,” Gertrude recalled, “as my own mother used to do; for now I was only one of many little animals driven by a herder.” In an article for Atlantic Monthly several years later, she wrote, “Like a slender tree, I had been uprooted from my mother, nature, and god. Now a cold bare pole, I seemed to be planted in a strange earth, trembling with fear and distrust. Often I wept in secret.”

As did tens of thousands of other Native American students, Gertrude became a child who straddled two worlds, belonging in neither. It was an ambivalence that would haunt her throughout her life, eventually destroying her relationship with her mother and distancing her from her tribe. In a 1913 letter to a friend she complained, “I seem to be in spiritual unrest. I hate this eternal tug of war between wild and becoming civilized. The transition is an endless evolution, that keeps me in a continual purgatory.”

Over the next three years, Gertrude became relatively fluent in spoken and written English. Returning home, she discovered that she no longer felt a visceral connection to her mother’s traditional lifestyle. Nor was her mother inclined to tolerate this child of two cultures. “During this time,” she wrote in a 1900 article for the Atlantic Monthly, “I seemed to hang in the heart of chaos… . My mother had never gone inside a school house and so she was not capable of comforting her daughter who could read and write. Even nature seemed to have no place for me.”

After four years on the reservation, she returned to White’s Institute to complete her education. She then entered the Quaker-run Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana, where she excelled as a poet, essayist, and orator. Her debating skills won her several prizes, and a number of her works were published in the college newspaper.

However, her ambivalence toward assimilation was evident in her work. In 1896, as a representative of Earlham College, she delivered an award-winning speech titled “Side by Side,” at the 22nd Indiana State Oratorical Contest. In it, Gertrude spoke movingly about the Indian’s right to seek vengeance for the wrongs inflicted on him and his way of life: “The white man’s bullet decimates his tribe and drives him from his home. What if he fought? ... Do you wonder still that in his breast he should brood revenge?” In the same speech, with equal intensity, she stressed her desire to see her people become a part of the American mainstream: “We come from mountain fastnesses, from cheerless plains, from far-off low-wooded streams, seeking the ‘White Man’s ways’ … seeking the Sovereign’s crown that we may stand side by side with you in ascribing royal honor to our nation’s flag. America, I love thee. ‘Thy people shall be my people and thy God my God.’”

An extended illness prevented Gertrude from graduating, and she left Earlham following her sixth trimester. Fearing a confrontation with her mother, she chose not to return to the reservation. Instead, Gertrude—now a slender, striking woman of 21—decided to teach Indian children and took a job as an instructor at the Carlisle School. This was the institute founded by the same Richard Henry Pratt whose solution to the Indian “problem” was total acculturation. “The school’s narrative … judged all that was Christian and white as good, and all the attributes that marked indigenous peoples as constituting heathenism,” writes Tadeusz Lewandowski in his biography of her, Red Bird, Red Power: The Life and Legacy of Zitkala-Ša. It was a philosophy that Gertrude would soon come to reject.

During this time I seemed to hang in the heart of chaos, beyond the touch or voice of human aid ... My mother had never gone inside of a school house and so she was not capable of comforting her daughter who could read and write. Even nature seemed to have no place for me. I was neither a wee girl nor a tall one; neither a wild Indian nor a tame one. This deplorable situation was the effect of my brief course in the East.

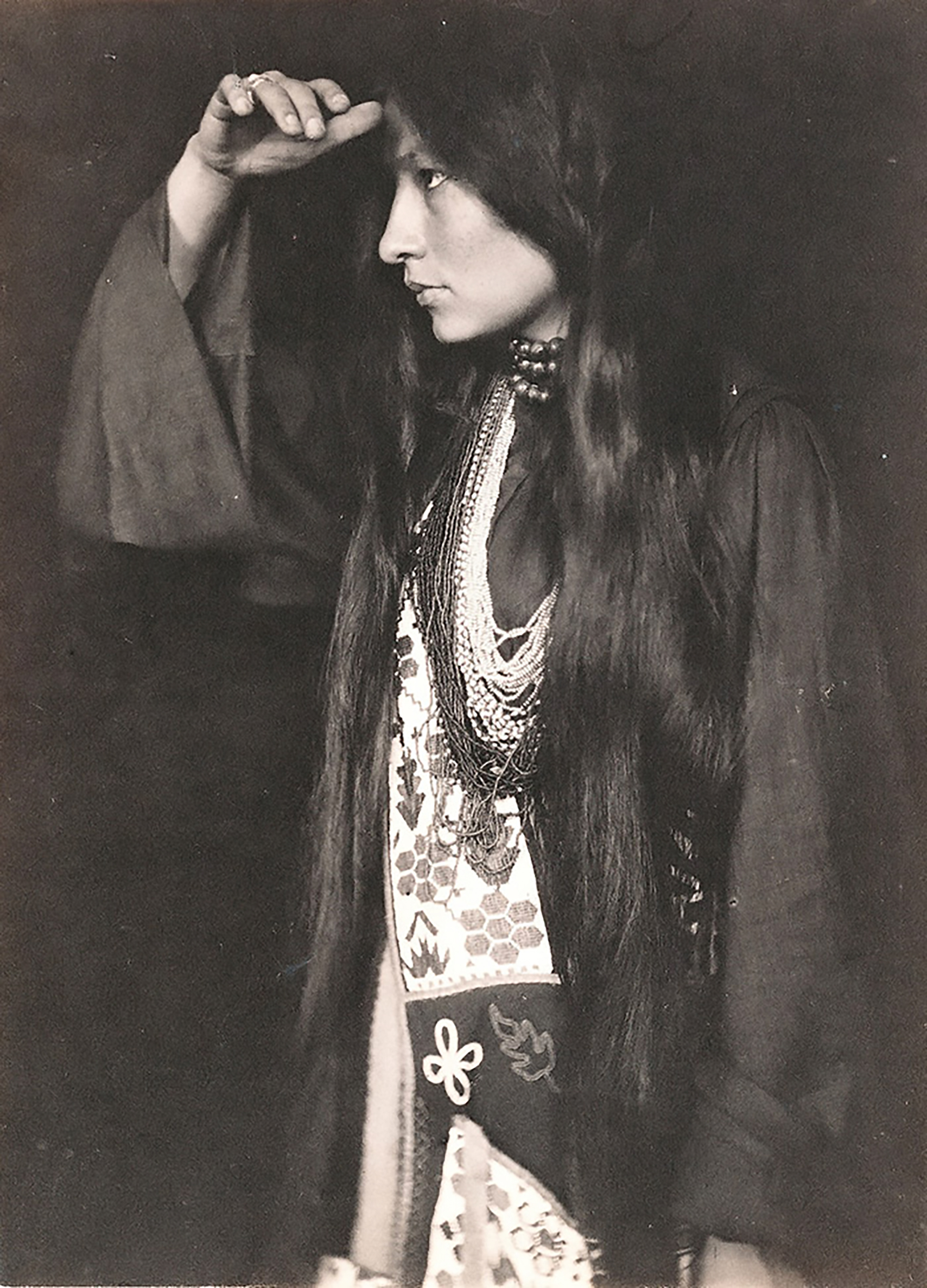

She had begun to play the violin at Carlisle and showed a true talent for the instrument. On her spring break in 1899, she traveled to New York City to further her studies. It was around this time that she met Gertrude Kasebier, the most noted female photographer of her era. The two became fast friends, and Kasebier and her colleague, Joseph Keiley—who was captivated by the young writer’s delicate beauty—took a series of romantically posed photographs, featuring the young author in both modern and tribal dress. The prints sold in 1900 for an impressive $1,000 apiece, a value of over $33,000 today.

Traveling to Boston, Gertrude engaged a highly renowned violin instructor from the New England Conservatory of Music. Something of a prodigy, she attained a proficiency that would one day see her perform at the White House for President and Mrs. McKinley.

Gertrude’s writing flourished as well. She had begun to write both autobiographical articles and tales derived from her tribal culture. In 1900, three of her pieces were published in the Atlantic Monthly: “Impressions of an Indian Childhood,” “The School Days of an Indian Girl,” and “An Indian Teacher Among Indians.” In addition to telling her story in beautifully wrought text, each work was a clear-cut, searing indictment of both the Indian boarding school system and the “Palefaces’” treatment of the American Indian in general.

She also created a Lakota nom de plume, for the first time signing her articles Zitkala-Ša, meaning Red Bird. Her work was widely applauded, and Gertrude found herself the darling of the Boston literary circle. Harper’s Bazar praised her “beauty and many talents” in its “Persons Who Interest Us” column, and The Outlook featured her as well.

Both magazines, however, missed the point of her writings, tending to focus instead on her “progress” from barbarism to civilization. Before becoming “civilized,” wrote Harper’s, she was “a veritable little savage, running wild over the prairies.”

Joseph Turner Keiley, 1898

Joseph Turner Keiley, 1898

Not surprisingly, Richard Henry Pratt was furious. Viewing his young teacher as both wrongheaded and ungrateful for the opportunity he had given her, he publicly denounced both her and her writings. Nor was he alone in his criticism. Many of Carlisle’s teachers looked at her as misguided at best, and libelous at worst. As Zitkala-Ša, however, Gertrude Simmons had found her voice as the spokesperson for her people. There would be no going back.

Honoring an earlier commitment, Gertrude temporarily returned to Carlisle to participate as solo violinist and orator in the 53-piece school band’s tour of the Northeast. The tour was an unqualified success, with Gertrude’s violin playing and recitation from Longfellow’s “Song of Hiawatha” the featured event. “She held every ear,” read one newspaper review, “and the recourse frequently to handkerchiefs told how great an effect she was exerting over her audience.”

Eventually tiring of her life among the Boston literati, Gertrude returned to the Yankton Reservation in the early 1900s, where she met and wed Raymond T. Bonnin, an Indian Bureau employee of mixed Yankton and Anglo ancestry. The two followed his job to the Uinta and Ouray Reservation in Utah, where they spent the next several years. Here, she bore her only child, a son. After the publication of her 1901 book Old Indian Legends and a few pieces for Harper’s Magazine and the Atlantic Monthly, including the provocative “Why I Am a Pagan,” she temporarily shelved her writing to work as a teacher and organizer of women’s community programs.

A few years later, Gertrude awakened her muse, resumed her writing, and collaborated with Mormon music teacher William Hanson in the creation of the well-received Sun Dance Opera. Framing the work around Sioux songs, religion, and oral history, she used her violin to transcribe traditional pieces, in a work that was both eerie and hypnotic.

Ironically, despite her long-professed aversion to organized religion, Gertrude converted to Catholicism. She also launched an anti-peyote campaign, in direct opposition to the Utes’ use of the drug for religious purposes. Citing its degrading qualities, she lectured at temperance and women’s rights meetings across the Midwest.

In 1914, the increasingly politicized Gertrude joined the Washington, D.C.-based Society of American Indians, a recently founded organization—the first national American Indian right organization run by and for American Indians—that promoted Indian self-determination and assimilation. She and Raymond moved to D.C., and Gertrude became the society’s secretary and chronicler. Within a few years, however, lack of public interest and internal dissension—much fomented by Gertrude herself—fractured the organization. She left the society, and in 1921—the same year that saw the publication of her American Indian Stories—partnered with the General Federation of Women’s Clubs (GFWC) to found the National Indian Welfare Committee. Shortly thereafter, she embarked on a GFWC-sponsored nationwide speaking tour on behalf of Indian citizenship, which would not be secured until 1924, when President Calvin Coolidge signed the Indian Citizenship Act.

Since the day I was taken from my mother I had suffered extreme indignities. People had stared at me. I had been tossed about in the air like a wooden puppet. And now my long hair was shingled like a coward's! In my anguish I moaned for my mother; but no one came to comfort me. Not a soul reasoned quietly with me, as my own mother used to do; for now I was only one of many little animals driven by a herder.

By now, the Yankton Sioux writer and activist who had become known as Zitkala-Ša had found her home in the realm of national politics. Her writings and presentations were becoming increasingly aggressive, as she made the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) her special target, and Indian rights her primary cause.

In 1924, not content with working from behind the pen or the lectern, Gertrude—along with two other activists—traveled to Oklahoma under the dual auspices of the GFWC and the Indian Rights Association, to investigate the outrages being perpetrated against the Osage. The tribe had found oil under the state’s hardscrabble ground, and many tribal members had become rich overnight. Corrupt white local courts immediately assigned the wealthy Osages “guardians”—parasites who systematically victimized them. Some whites married into Indian families just to claim their wealth. And what they couldn’t steal by guile they acquired through murder.

The result of the investigation was an extensive paper, coauthored by Gertrude and titled “Oklahoma’s Poor Rich Indians: An Orgy of Graft and Exploitation of the Five Civilized Tribes—Legalized Robbery.” It was a scathing, gut-wrenching exposé, and the trio’s goal was to use it to force a congressional hearing. It worked, but not in the way they were hoping. The committee whitewashed the whole affair, discounting the treatise and unofficially declaring a vendetta against members of government who had supported the effort.

That same year, however, a bright note helped to lessen her disappointment: Congress finally passed the law granting Indian citizenship. It was a cause for which Gertrude had fought hard, and she was justifiably proud. As she succinctly wrote on a personal list of annual accomplishments, “Helped get Act through Congress granting citizenship to all Indians.”

In 1926, Gertrude created her own nonprofit pan-Indian organization, the National Council of American Indians, with husband Raymond as secretary-treasurer. The two drove thousands of miles, visiting countless reservations in their effort to unite America’s tribes in common cause. She wrote a regular newsletter and appeared before Congress with well-documented accounts of the abysmal living conditions and historic wrongs suffered by her people.

Unfortunately, over the next several years, political dissension among the leading Indigenous groups played a significant role in lessening their overall impact, and although Congress passed the groundbreaking Indian Reorganization Act in 1934, Gertrude was ultimately disappointed in the results of her decades-long efforts. In a letter to a friend the following year, she wrote, “[T]hough it took a lifetime, the achievements are scarcely visible!!!”

Gertrude was plagued by a variety of ailments throughout her adult life. On January 25, 1938, she fell into a coma, and unexpectedly died of what were diagnosed as kidney disease and cardiac dilation. The autopsy merely listed her as “Gertrude Bonnin from South Dakota—Housewife.” Raymond died less than four years later; owing to his earlier military service, he and Gertrude share a tombstone in Arlington National Cemetery. Under Raymond’s name, the inscription reads:

“His Wife / Gertrude Simmons Bonnin / ‘Zitkala-Ša’ of the Sioux Indians / 1876–1938.”

Ultimately, Gertrude Simmons Bonnin—the half-Sioux poet-activist who renamed herself Zitkala-Ša—was a study in contradictions. She represented her people and fought for Native American rights, while working hard to establish herself in the “Paleface” society that she often railed against. The author of a heartfelt piece titled “Why I Am a Pagan,” she embraced various Christian sects during her 61 years, including Catholicism, and was given a Mormon funeral. She fought hard for the preservation of Indigenous customs yet waged a bitter campaign, alongside her former adversary, Richard Henry Pratt, against the traditional tribal use of peyote. She disparaged the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ boarding-school methods of educating and assimilating Indian children but sent her only child to a strict Catholic school. A lifelong advocate for her people, she nevertheless found it impossible, once she had been exposed to an Anglo education, to live among them. And while touting the need for maintaining the sanctity of Indian traditions, she allowed herself, in the words of editor Dr. P. Jane Hafen, to “pander to sentimental, colonial images,” at various times falsely claiming to be Sitting Bull’s granddaughter.

“She spent her life in balance between two worlds, using the language of one to translate the needs of another,” author Dexter Fisher asserts. “She was in a truly liminal position, always on the threshold of two worlds but never fully entering either.”

Considered within the context of her gender- and racially restrictive era, however, Gertrude Simmons Bonnin’s accomplishments were truly remarkable, and all achieved while straddling a lifelong rail between two cultures that were alternately demanding and unforgiving. She was instrumental in attaining universal suffrage for America’s Indians, and—while helming a powerful organization that she herself had instituted—in exposing corruption and ineptitude at the highest levels of government.

I was not wholly conscious of myself, but was more keenly alive to the fire within. It was as if I were the activity, and my hands and feet were only experiments for my spirit to work upon.

As Zitkala-Ša, she wrote movingly and lovingly of the history, lore and suffering of her people, soaring, as Red Bird, above the restraints of the times and the two worlds that bound her.

Gertrude Kasebier, c. 1898 / National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institute

Gertrude Kasebier, c. 1898 / National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institute