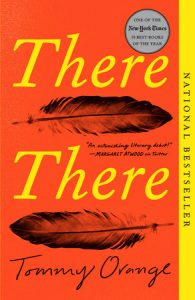

C&I talks with the author of one of the most acclaimed and talked-about works of literature — Native or otherwise — in recent years, There There.

Tommy Orange hoped his peers in his Institute of American Indian Arts creative writing program and the Native American writing community would appreciate There There, his debut novel. Maybe other Native people from Oakland, California, where he grew up and where the book is set, would like it too. As ambitious as the book was — with its 12 narrators each telling part of the story from his or her own point of view, the plot and connections between characters gradually clicking into place until the breathtaking action of the climax at a powwow in the Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum — his expectations for its reception were modest.

So far, There There (Knopf, 2018) has been nominated for the National Book Award and the American Library Association’s Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction, earned nearly unanimous critical acclaim, sparked conversations about representation of Native Americans in literature and entertainment, and been optioned for a screen adaptation. (Update: Add the 2019 PEN/Hemingway Award to that list.)

Not bad for his first published work of fiction.

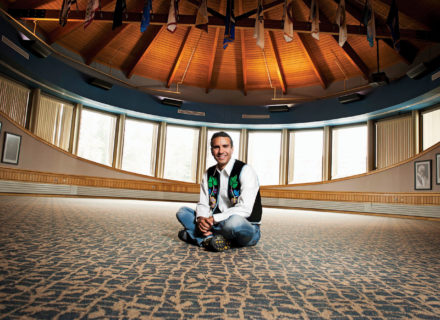

Orange is an enrolled member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma, the son of a white mother and Native father. Like most of his book’s characters, he is an “urban Indian,” born and raised in Oakland — something of a departure from many of the most familiar and influential Native writers, whose works are often set on reservations.

There There portrays an array of city-dwelling Native people, including a teenager who secretly teaches himself to powwow dance by watching YouTube videos, a reclusive internet addict, a recovering alcoholic coming to grips with the effects of leaving her family, an MF Doom fan marked by fetal alcohol syndrome, and a crew of young men armed with 3D-printed guns who hatch a cruel heist, among others.

The book also describes parts of Oakland so vividly that by the end, the city feels familiar even to someone who has never been. In fact, the title comes from what Gertrude Stein wrote about the city — not to belittle it, but because urbanization meant it was no longer the pastoral Oakland of her memory — that “there is no there there.” Some of the novel’s characters openly or unconsciously long for the rougher, grittier past of the rapidly gentrifying city. (The Radiohead song “There There” also gets a mention early in the book.)

We talked to Orange a couple of weeks after the National Book Award finalists were winnowed down to the shortlist. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Cowboys & Indians: Congratulations on making the long list for the National Book Award. I was sorry to see There There didn’t make it to the shortlist. Did you expect it to get all the acclaim it has?

Cowboys & Indians: Congratulations on making the long list for the National Book Award. I was sorry to see There There didn’t make it to the shortlist. Did you expect it to get all the acclaim it has?

Tommy Orange: No, not at all. I graduated May 2016, and really wanted to finish it before I graduated because the director of my school, the Institute of American Indian Arts, told me I could get a teaching job if I had a book. So it was a very basic goal with the book: to get a teaching job.

C&I: It is a really ambitious book, though. Did you have any idea that it would be seen as so important, or have any intentions for it to be?

Orange: No. I thought people in my Native writing community and maybe Native people from Oakland might appreciate it. I hadn’t published anything, so I wasn’t thinking in terms of this is going to do anything, so it’s been a complete surprise.

C&I: There There is told from the point of view of several different characters. Were there any in particular you most identified with?

Orange: No, I think they’re all more me than anybody else, but I didn’t particularly. There’s one person, Thomas Frank. We share first and second names, and there’s more straight-up biographical details from my family experience, so my family reads that chapter differently than most people would. But all the characters resemble me more than they do other people.

C&I: The 3D-printed guns were a great element to the story. They added such a sense of dread throughout. You just know something bad is going to happen. Of course, any gun can do that, so I wonder what was the significance of them being 3D-printed — assuming there was one beyond getting them through the metal detectors?

Orange: Um, yeah, that was a basic logistic thing.

C&I: Oh. [Laughs.]

Orange: But everything I did in the book that’s related to modern technology and contemporary behavior had to do with revisiting the idea of the historical monolithic Native American that everyone thinks of, and that ... the only real way to be a real Native American is to be historical or have a headdress or look this one way. It’s deeply damaging to a people to not have a dynamic range of ways to be that are still acceptable as Native. One of the common experiences of being a Native is to be questioned, like: Are you enough? So I wanted it to feel very contemporary and now. Also, just having the feeling that it’s right now. I happened to be at an artisan residency, and I was watching an artist’s presentation — or I wasn’t watching one artist, I was watching this 3D printer spool something out — and the idea just kind of popped into my head.

C&I: One thing in the book I was really obsessed with was the spider legs coming out of a lump in a character’s leg. Did that come from a real-life incident or family folklore?

Orange: No, it happened to me. I didn’t really understand it, and I couldn’t find anything on the internet, any answers. I asked my dad what he thought, because it seemed like an Indian thing to happen. He didn’t have any answers for me. He said, “It sounds like somebody witched you.” So I was just kind of scared of that answer. And then there were some other spider things that started happening in the novel at that point. This was maybe 2013 or ’14, and I had nothing else to do with it, so I figured, why not use it in the book?

C&I: So it happened while you were writing it?

Orange: Yeah.

C&I: Wow. That’s crazy.

Orange: [Laughs.] Yeah, it was. I guess it still is crazy.

C&I: Do you still have the lump on your leg?

Orange: I do.

C&I: And nothing else came out of it?

Orange: Nope. [Laughs.]

C&I: I don’t suppose you asked a doctor about it? Sorry to dwell on this, it’s just fascinating.

Orange: It’s OK. No, I haven’t had good experiences with doctors. There was nothing else after that came out or even anything else leading up to it that seemed alarming for my health. I haven’t been to a doctor in a long time.

C&I: Your father was a leader in the Native American Church and your mother left that religion for evangelical Christianity and then came back. Were you ever drawn to either faith, or are you religious now?

Orange: I kind of was forced into it as a kid, into the evangelical part, and then I spent time around ceremony — Native American Church ceremony — when I got older, 18 to 25. I went to ceremony, not regularly, but I had many experiences in the tepee. But ultimately, I am, but not under those two things. It’s more of a different way of looking at the world. It’s not under a particular religion.

C&I: You started out as a musician and went to school for sound art. Do you still create music?

Orange: I do. I’ve got a bunch of piano compositions that I’ve just slowly over the years been building, adding on to. It’s very much a private thing that I love to do. I still play guitar and piano. It’s just more of a private activity.

C&I: Do you plan to keep it private?

Orange: For now. I’ve experienced a lot of exposure, as you can imagine, with the book. So I can’t imagine — I don’t even know if I would want to release any music under my name because of the exposure, and because it’s very personal work for me. I’ve had to develop tough skin pretty fast for the book. If I were ever to do it, it might be a smaller thing under a pseudonym.

C&I: What else are you writing? Are you working on a follow-up yet?

Orange: There’s a couple essays. I just wrote a book review [of Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah’s story collection Friday Black] for The New York Times. I’m working on a couple new books. One of them is more autobiographical, about my family, and I’m kind of interviewing them, and have told them about it and they’re OK with it. And I have another book I’m pretty deep into, and I have a deadline with my agent for December [2018]. But I’m not really talking too much about it yet.

There There is available at booksellers and on Amazon. You can find out more about the book and author at penguinrandomhouse.com and follow Tommy Orange on Twitter at @thommyorange.

Photography: Courtesy Elena Seibert