Larry Mahan is a legend in and out of the saddle. For all his many accomplishments, the hall-of-famer credits his love of horses and would like to thank the ponies who carried him.

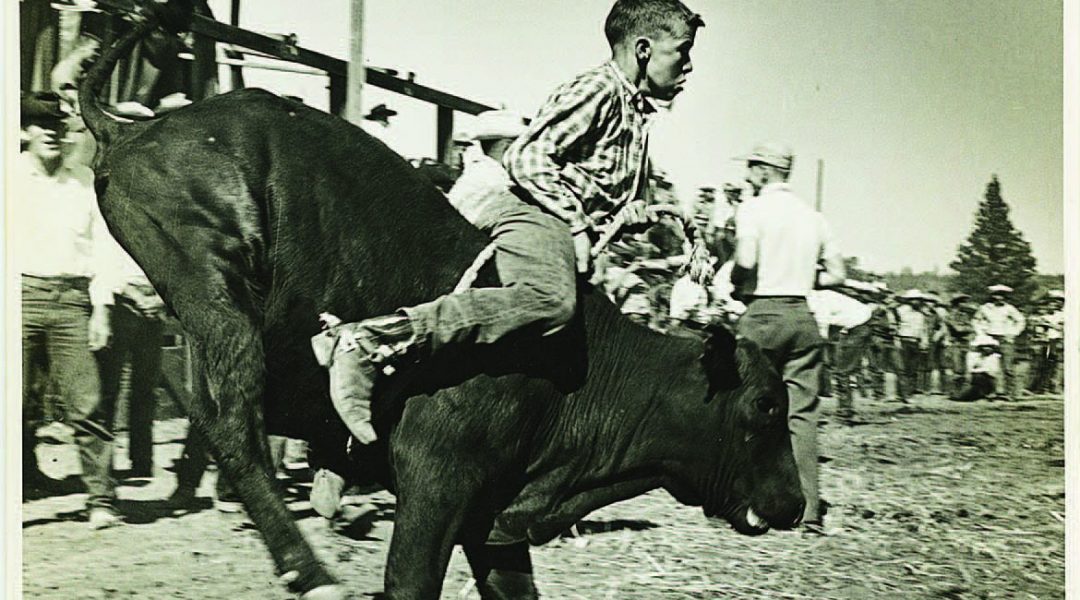

The love affair began when Larry Mahan was a kid in Brooks, Oregon.

“I think my folks bought me my first horse for about $125 when I was probably 7 years old,” he says. “She was half Arab, half quarter horse, no papers, and we had her around three or four months, five months, and she had a colt — we didn’t even know she was bred — and I was just so in love with horses and riding.”

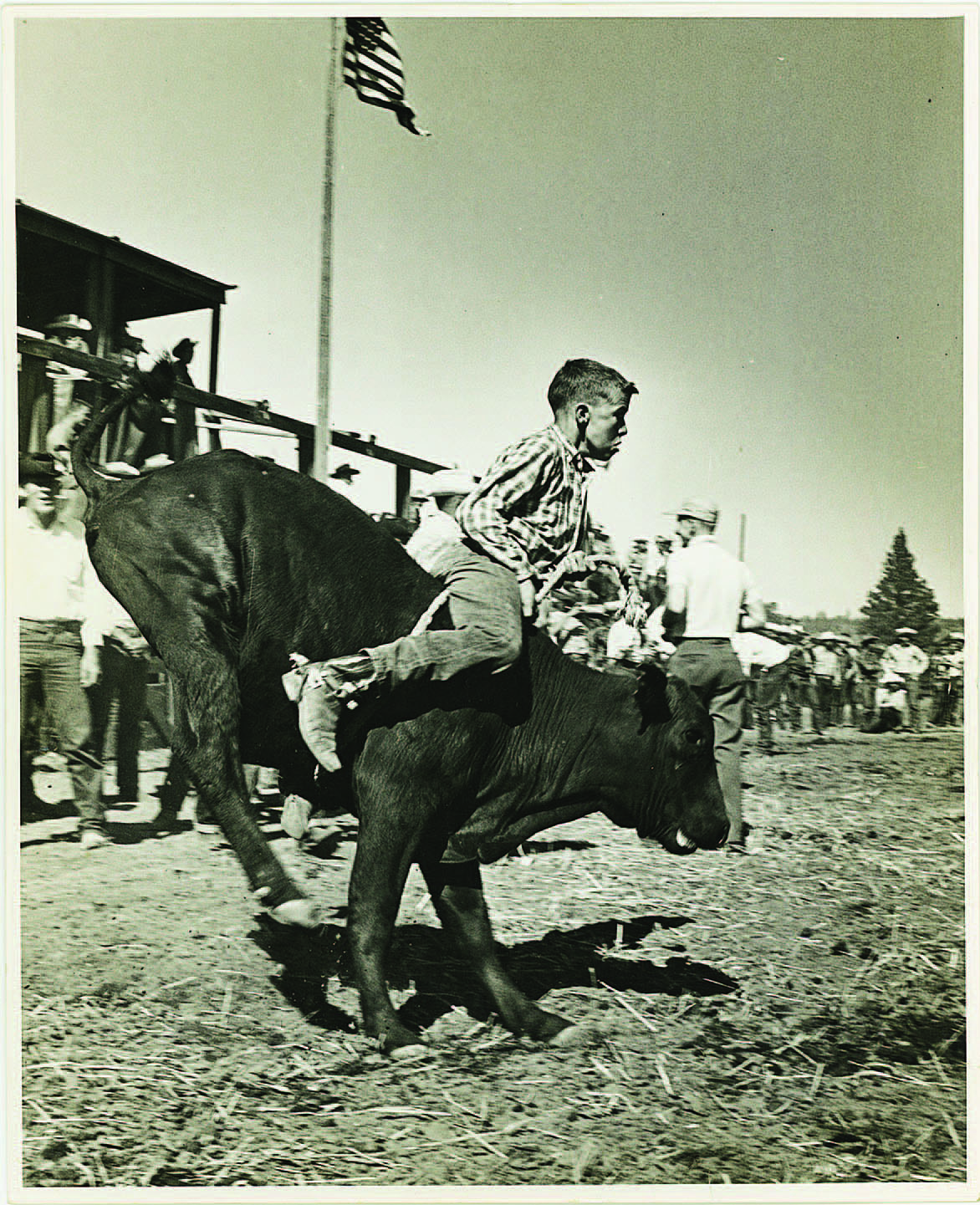

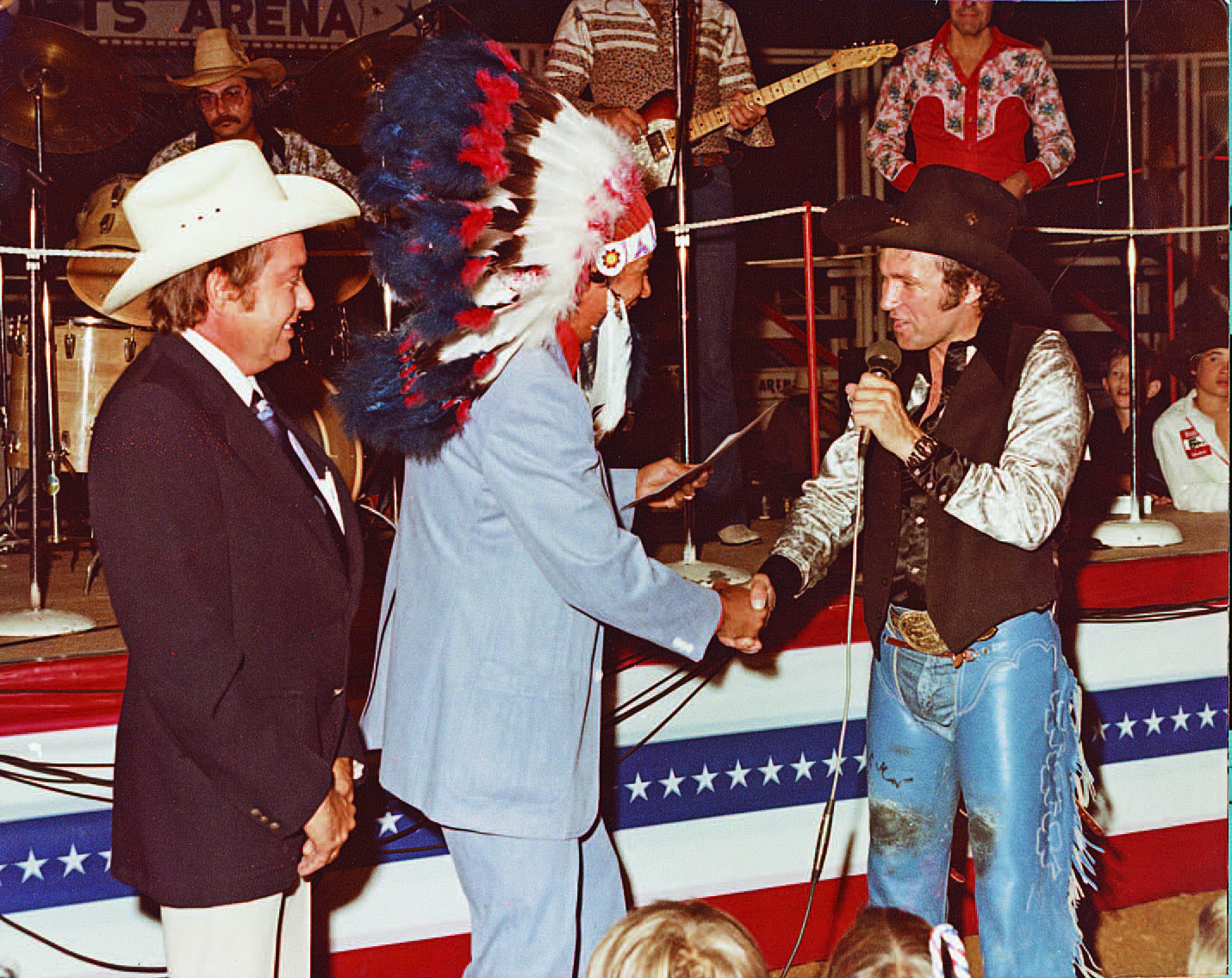

Sydney, Australia, 1978.

Sydney, Australia, 1978.

He has loved every one of them since. Even the rankest broncs that tried to launch him into the stratosphere during 10 rounds of the National Finals Rodeo — rodeo’s version of the Super Bowl. He has driven pickups to countless rodeos, a Jaguar through Beverly Hills, and piloted his own twin-engine 310 Cessna across America — he even soloed a P-51 — but the horses, he says, have carried him.

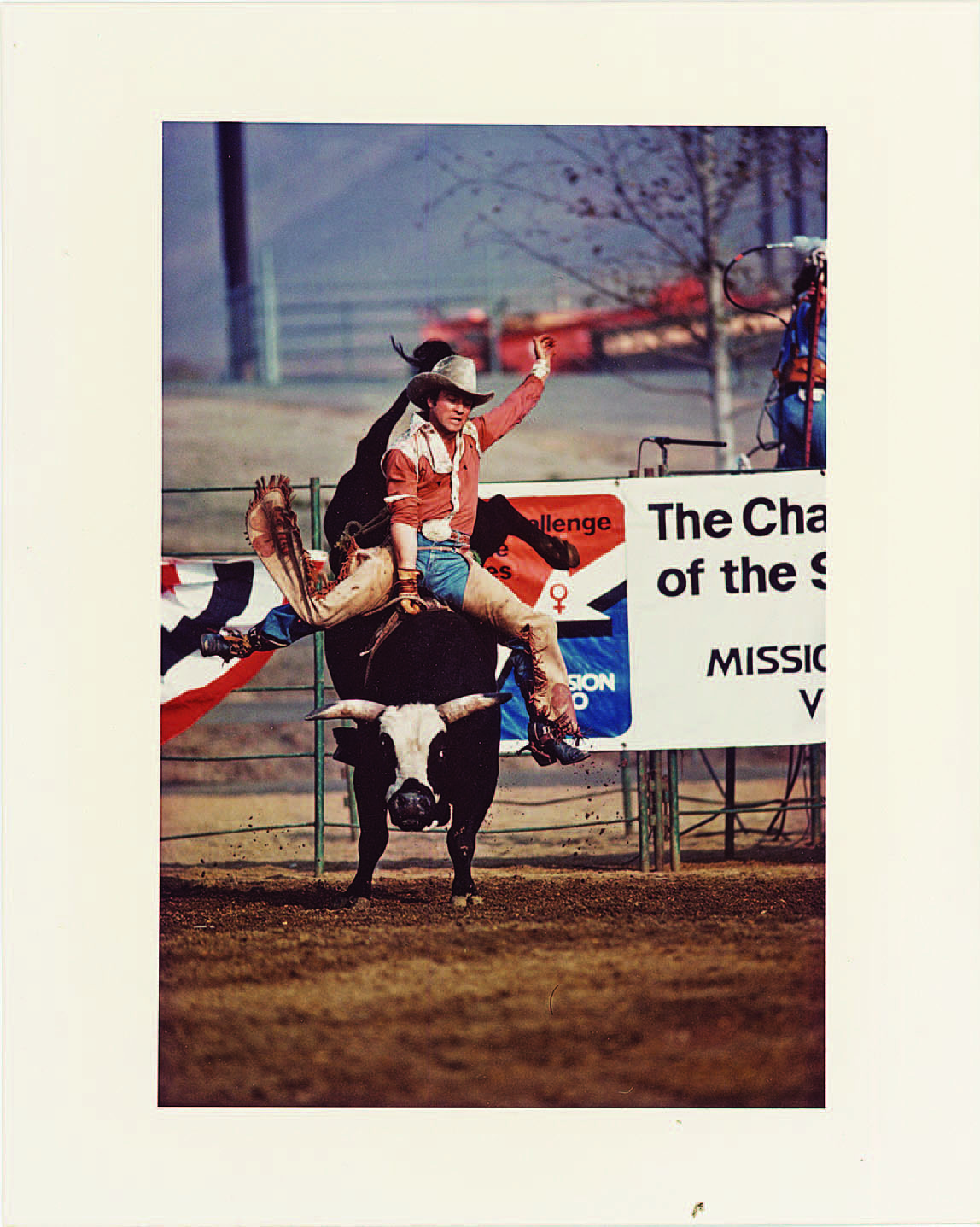

A handful of past PRCA champion were invited — me, Jack Roddy, Monty Henson, among others. This bronc flipped in the chute, and they gave me a re-ride — the same horse! When the whistle blew, I fanned my hat and jumped off. Unfortunately, I badly sprained my knee. I made the finals, but it was a very long 15-hour flight home.

To success in rodeo and other arenas.

And through the worst of times.

“It has been an interesting journey,” Mahan says. “And I’m definitely qualified to be a ‘Road’s Scholar.’”

The journey includes eight world championships — six All Around and two Bull Riding — in the Rodeo Cowboys Association (which became the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association in 1975). He was the first competitor to qualify in all three roughstock events (bull riding and bareback- and saddle-bronc riding) in the NFR; and set a record — that still stands — by qualifying 26 times in NFR roughstock events.

“He was the epitome of being a world champion,” says Bill Pierce, who chaired the Frontier Days Rodeo in Prescott, Arizona, from 1966 to 1971. “He related to people, he related to his fellow contestants. He was Mr. Rodeo.”

Mahan followed that with forays into acting (his favorite part was in the 1995 made-for-TV The Good Old Boys, directed by and starring Tommy Lee Jones); music (Warner Bros. released his LP King of the Rodeo in 1976); and putting his name on Western clothing, boot and hat lines (Dorfman Milano still produces Larry Mahan Hats).

Even after his last rodeo, Mahan didn’t stop riding. He earned more than $132,500 in National Cutting Horse Association competitions, including a 1989 Derby Non-Professional Reserve Championship, and won the consolation round at the Reno Invitational Team Roping championship with Sherrick Grantham in 2011.

He has been interviewed on television by Johnny Carson, Dick Cavett, Mike Douglas, and Dinah Shore; was host of the TV series Horse World; and wrote a book, Fundamentals of Rodeo Riding: The Physical and Mental Approach to Success. Since 1973, he has “slowly” been working on an autobiography. He’s also the subject of a forthcoming documentary, Teton Ridge Entertainment’s The Cowboy. And he remains a leading ambassador for rodeo.

Mahan’s sitting inside his Spanish-style house overlooking “a beautiful horse facility” of 80 acres in Valley View, Texas, which serves as headquarters for the horse and cattle operation; another ranch lies two-plus hours north in Ada, Oklahoma.

Mahan turns 79 on November 21. “I’ve had an opportunity to live four quarters of the game, and it’s in overtime as far as I’m concerned,” he says. “And you learn to appreciate every day.” He’s ready to reflect on a life of records and triumphs, broken bones and broken hearts, the good, the bad, the ugly — and horses. It was, after all, “through the love of horses that I got turned on to the rodeo game.”

In 1957, he entered calf-riding at a kids rodeo and won $6 and a buckle — the latter now displayed at the Pro Rodeo Hall of Fame in Colorado Springs, Colorado. “From that point on,” he says, “I was hooked on the feeling.” By the time he turned 15, he had started riding bareback bucking horses and saddle broncs. Armed with a brand-new RCA permit in 1960, Mahan entered his first rodeo in Klamath Falls, Oregon. “I won the bull riding,” he recalls. “Rode two bulls and won $240. That was the beginning of becoming an adrenaline junkie.”

My first belt buckle and check at age 14 in the calf riding. I was on my way! The buckle is on display at the PRCA Hall of Fame.

Out of high school and set on becoming a professional rodeo cowboy, he moved to Arizona in 1962 with his new wife, Darlene, landing a job working in livestock sale yards for $1.10 an hour. Out-of-state tuition dashed the original plan of enrolling at Arizona State University and joining the rodeo team. Instead, Mahan traveled to rodeos — mostly amateur, but a few pro competitions — in Arizona, New Mexico, and occasionally California.

He practiced as much as he could. Many contractors let him ride their bucking stock. In 2002, Harry Vold, a stock contractor for many rodeos, including the NFR, told me that Mahan would ride every animal he could that other competitors had turned out for various reasons. I said, “That shows a lot of determination.” Vold quipped: “He was a pain in the ass.”

Hearing the story, Mahan roars with laughter, then recalls: “Harry was at some rodeo when I jumped on what I thought was a horse another cowboy had turned out. And a cowboy is wondering where his horse is. Harry looks at me and says, ‘You little dummy, that’s not the horse you’re supposed to be on.’”

Mahan kept riding, watching, learning — and getting better. In February 1963, he won second in bull riding in El Paso and $852, putting him over the $1,000 threshold and allowing him to join the RCA.

That summer he paid $150 to enroll in 1962 saddle-bronc champion Kenny McLean’s bronc-riding school in British Columbia, riding 49 broncs in seven days. “I was so sore that I’d take paper plates and ACE bandages to wrap around my legs underneath my chaps,” he says. “It didn’t help.”

On the way home, he stopped to pick apples to pay for the next entry fee for a pro rodeo in Kanaskat, Washington.

“Boxes were probably four feet by four feet by four high,” he recalls. “You have to pick a lot of apples to fill one of those boxes, and we were paid $4 per box. The school helped my bronc riding, not the apple picking. But I knew for sure I didn’t want to be an apple picker.”

1964 arrived, and Mahan paid $200 for a roan saddle horse that wanted to buck. He took that horse with him to rodeos. “Hauling a practice horse around wasn’t the original plan, but before it was over, I had hauled that horse to several rodeos around the country. If nobody was around, I could tighten up the flank, push the chute gate open, and that horse would buck like crazy, jump and kick, for about seven seconds. I’d then pick up on the bronc rein and yell, ‘Whoa.’ He would stop, and I’d step down off him.”

He later sold the horse to a friend. “Turned out to be a kid’s horse.”

That year Mahan qualified for his first National Finals Rodeo in saddle-bronc riding in 15th place. He placed third in two go-rounds for about $360, finishing the weeklong event in the same slot, 15th, but his mother came to his defense. The Capital Journal of Salem, Oregon, ran an article about the former local youth turned rodeo rider. The eight broncs drawn by Mahan during the weeklong event included “a tough specimen called Trail’s End” that bucked him off, the newspaper reported. “According to Mrs. Weldon Stockton, Mahan’s mother, that particular horse has been tough for any rider. ‘Not many men can stay with him at all,’ she says.”

When I read that to Mahan, he laughs. “Oh, my goodness,” he says. “Lord. Wow. She was quite a gal.”

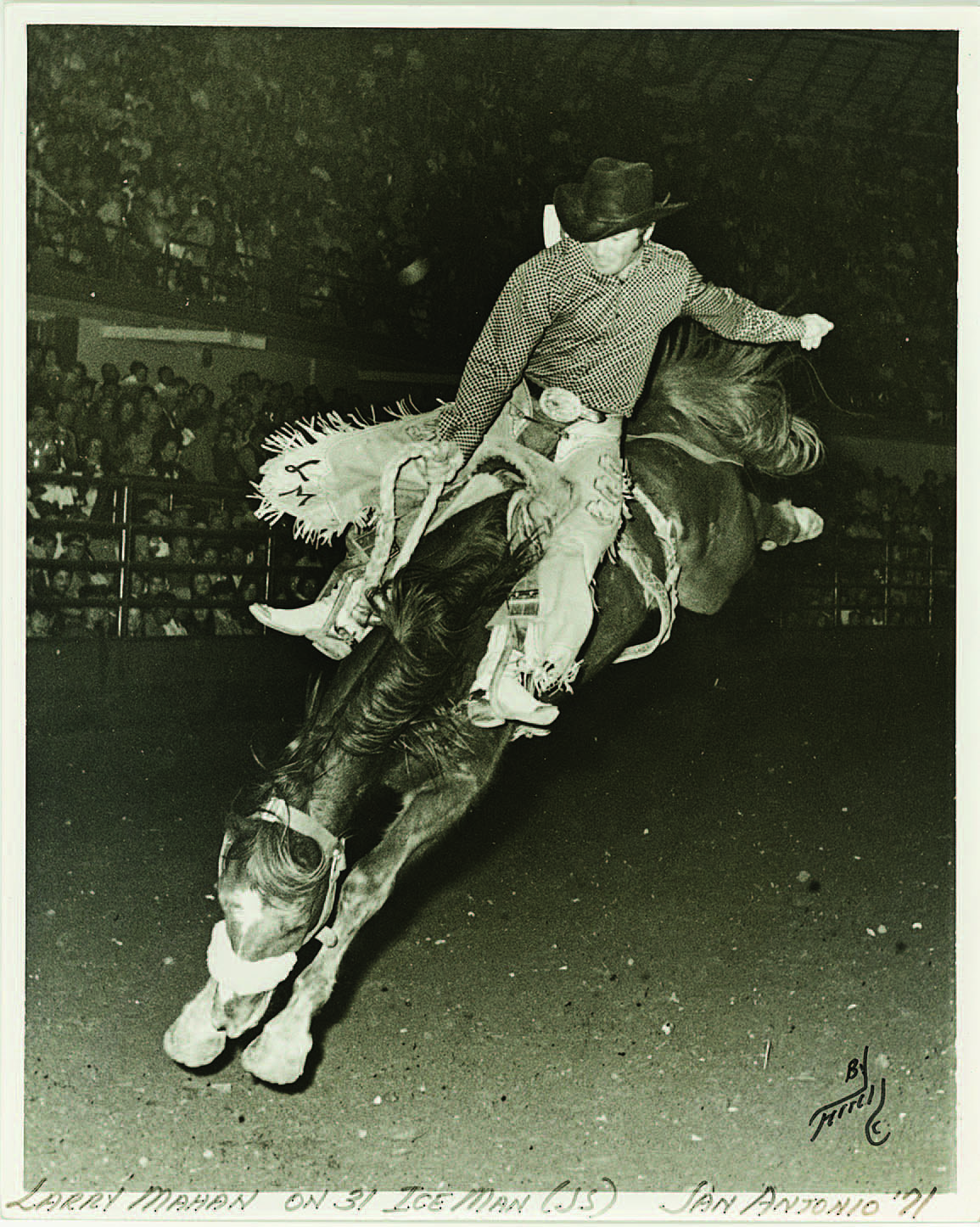

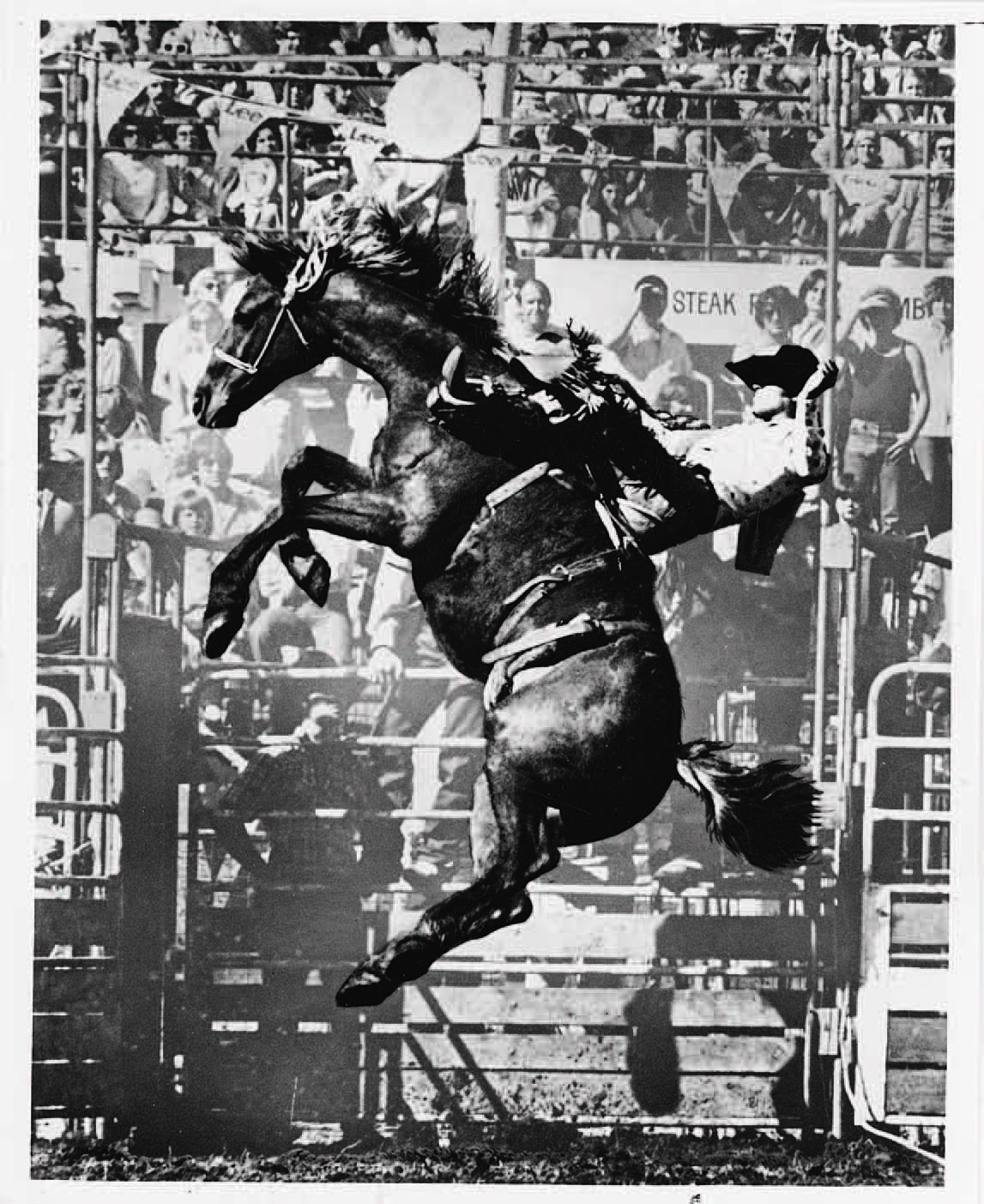

Mahan shown winning the Bullriding Championship at Cheyenne Frontier Days in 1970.

Mahan shown winning the Bullriding Championship at Cheyenne Frontier Days in 1970.

1964 had been a long year: a 1960 one-ton Ford truck fitted with a wooden horse box, pulling a 19-foot house trailer. Mile after mile, town after town, rodeo after rodeo. And the NFR was more of the same. “Parked the old camper out there by the [Los Angeles] Coliseum,” Mahan says. “That was how I rodeoed back then. It wasn’t staying at the Hilton or the Broadmoor or anyplace like that.”

By 1965, Mahan was traveling with other cowboys, usually leaving Darlene and 3-year-old daughter Lisa at home. Believing that he had a shot at winning the bull-riding championship, he started thinking about a better way of getting to rodeos. He and friend Shawn Davis, who would win the saddle-bronc title that year and again in 1967 and 1968, chartered an airplane to take them from South Dakota to Texas and other rodeos across the country.

“I instantly fell in love with flying — the technicality, sense of freedom, and peaceful aspect of the open skies,” Mahan says. He began taking flying lessons.

While still leading in bull riding, he hit a slump that summer. Any bull that turned left, the right-handed-riding Mahan fell off. After another no-score on a good bull, RCA secretary-treasurer Bill Linderman — “the kingpin of the rodeo association then” — approached Mahan. “I was just in awe that he came up to me,” Mahan says.

Linderman asked, “Hey, kid, can I give you some advice?”

“Yes, sir,” Mahan replied. “It sure looks like I need some.”

Linderman was to the point. “If you wanna win [a championship], you gotta quit falling off.”

As the season wound down, things improved, and Mahan arrived at the NFR in Oklahoma City with a sizable lead in bull riding. But those eight go-rounds proved humbling — bucked off seven bulls and “slapping” another for a no-score. But after the points were tallied, he left the NFR with the coveted engraved gold buckle: 1965 World Champion Bull Rider.

He worked harder, mentally and physically. By 1966, he had his pilot’s license and was flying to many rodeos. He won the all-around title in 1966, 1967, and 1968 with another Bull Riding Championship in 1967. Jim Shoulders’ record of five all-around titles set in 1959 became Mahan’s target. “I thought that would be a great record to achieve,” he says, “so that was my goal.”

He won all-around titles in 1969 and 1970 to tie the mark. Injuries in 1971 and 1972 — a season captured in the Academy Award-winning documentary The Great American Cowboy — ended any chance of besting newcomer Phil Lyne. But in 1973, Mahan won the record sixth all-around title. Ty Murray, whom Mahan befriended when Murray was 13, broke it in 1998. “Jim Shoulders set the bar, and I was blessed to have set the bar higher,” Mahan says. “I set the bar, and Ty Murray said, ‘That’s my goal.’

“I was really proud of Ty because I knew how hard he had to work for it in three roughstock events.”

Mahan quit riding bulls and bareback broncs in 1977 but continued to ride saddle broncs in a few choice events for a few more years before he retired. Well, not really retired. “Jim Shoulders said, ‘When you retire, you usually get a check every month. So you don’t retire from rodeo. You just quit,’” Mahan says.

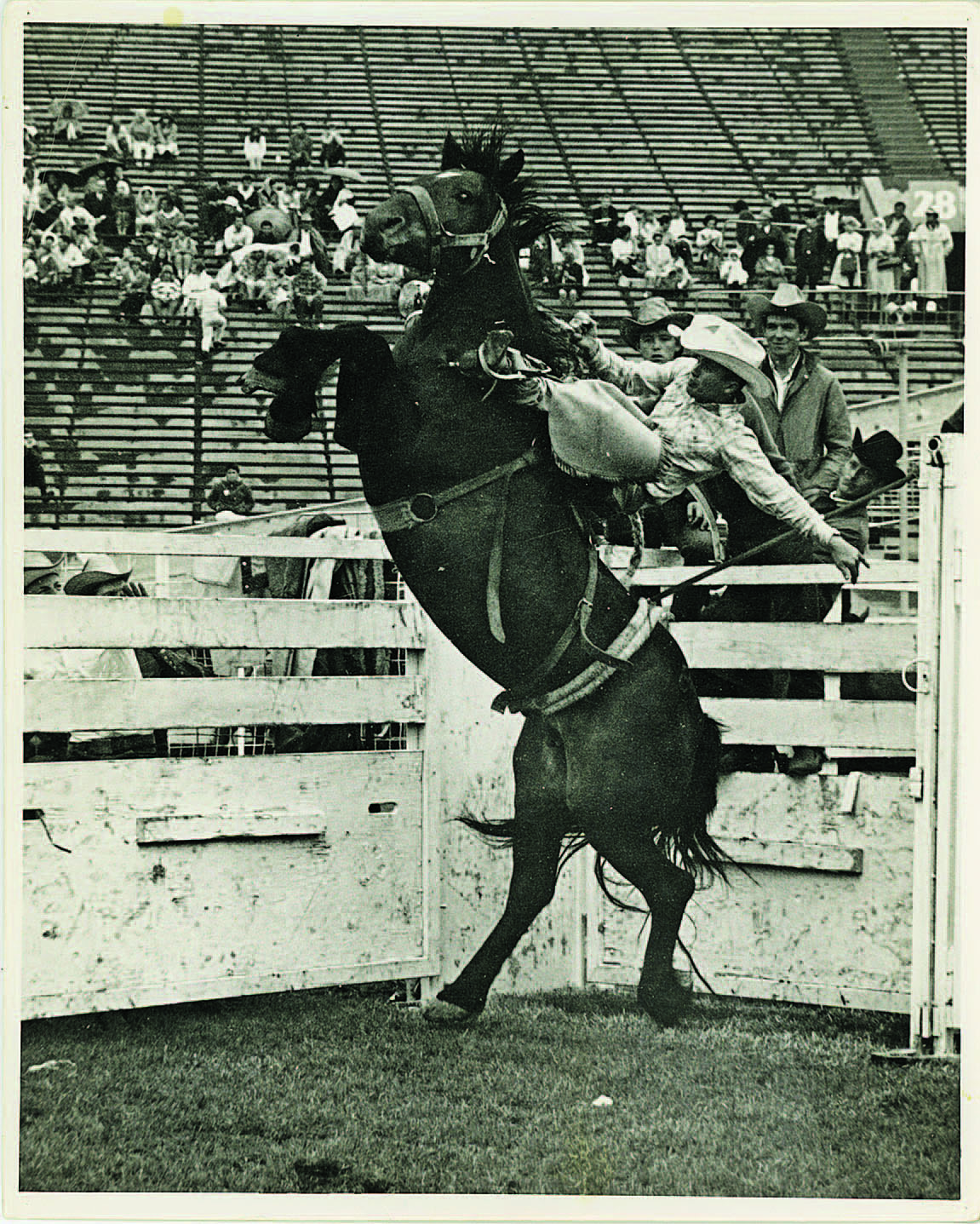

Mahan’s last major championship was in saddle-bronc riding in Prescott, Arizona, in 1979.

I commissioned an oil painting of this image, which hangs above my fireplace today.

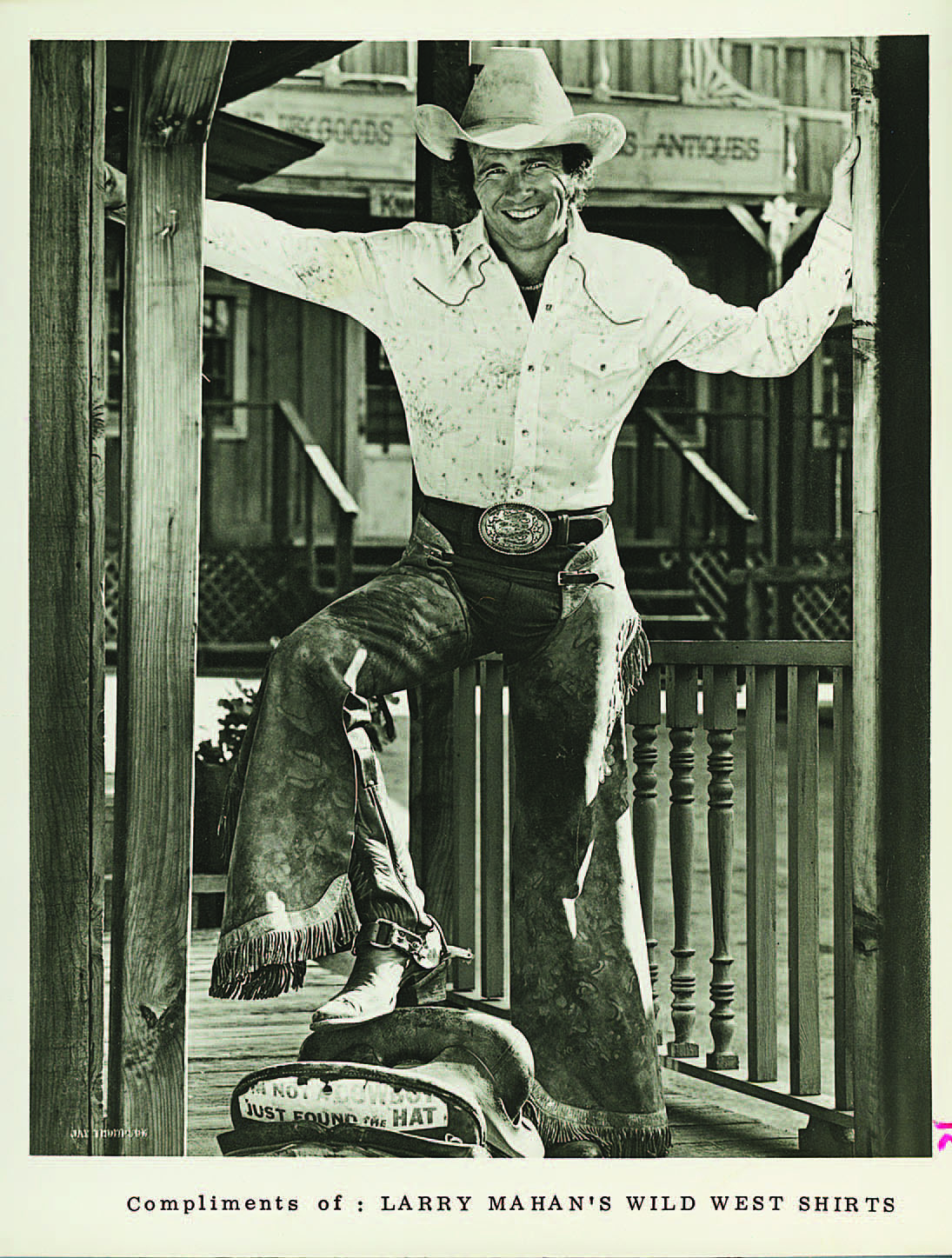

By the mid-1970s, other avenues had opened for Mahan when he met and hired Ted Steinberg, a young sports/entertainment attorney in Los Angeles, to negotiate endorsement agreements with various companies eager to add the Mahan name to their products. But Steinberg had other ideas. He persuaded him to form his own brand/label and engage in royalty/licensing contracts instead. Whereupon the Larry Mahan Cowboy Collection was trademarked for Western clothing, boots, and hats.

That collection gained popularity, from Fifth Avenue in New York and across Main Street USA to Aspen, Colorado … Santa Fe, New Mexico … Cutter Bill’s in Dallas and Houston … even Neiman Marcus. Mahan also credits the 1980 movie Urban Cowboy with exploding the Western apparel industry.

“It was exciting for me,” Mahan says, “because Western apparel represents the Western culture and lifestyle.”

Steinberg went on to represent many top sports figures, including basketball legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, tennis champion Martina Navratilova, and pro football quarterback Craig Morton.

Mahan moved to L.A. to study acting, landing parts on TV and in movies after acquiring his Screen Actors Guild card.

Then a get-together with music producer Snuff Garrett in Bel Air resulted in the notion that Mahan should cut an album.

“He’d invite me over to watch Roy Rogers movies, just the three of us — Roy, Snuffy, and me,” Mahan recalls. “They’d just finished Roy’s last album. I grew up watching Roy Rogers as a kid. I’d go into Salem every chance I could get to watch Roy, Gene Autry on the silver screen. [Garrett] said, ‘Mahan, you need to do an album.’”

Mahan wasn’t exactly enthusiastic, saying, “Snuffy, I’ve never had any desire to sing.” But Garrett — who had produced Cher, among others — approached Andy Wickham, then heading the artists and repertoire division for Warner Bros. When they met, Mahan sensed Wickham’s reluctance when Wickham asked Garrett, “Can he sing?” Garrett answered: “Well, if that SOB could sing, do you think he’d be riding bulls for a living?”

Shortly afterward, Mahan found himself in a recording studio. A band was hired, a bus purchased, and Mahan was on the road again.

He performed at many rodeos, where he “would come out on a saddle bronc, microphone in hand, and when the pickup man would drop me off, I’d start my first song, which I’d learned from Jerry Jeff Walker. ‘I’m a ro-de-o de-o de cowboy/Bordering on the insane.’ Heck, I couldn’t make this up.”

One of his musical highlights came when he opened for Waylon Jennings at Red Rocks Amphitheater near Denver, where, Mahan says, “it became obvious that the crowd of 8,000 screaming fans were there to see Waylon, not me.”

Mahan had met Jennings and Richie Albright, Jennings’ drummer and producer, years earlier in Arizona.

“I’d visit them whenever I was in Nashville,” Mahan says. “It was fascinating to witness the inner sanctum of Waylon’s studio—home of the original outlaw country music superstar.”

Another album recorded in Waylon’s studio with Waylon joining the sessions singing harmony and playing guitar is still on Mahan’s “drawing board.” It was almost completed in 1979 before Mahan pulled the plug. The reason: “I just really got over my addiction to the road.”

Because for all of the success, that road had been bumpy.

His marriage to Darlene, which produced daughter Lisa and son Ty, “hit the rocks in ’73, and that was my fault. I’ll take credit for that one. I moved to L.A., thought I’d take up acting, got a divorce. Probably made choices that I shouldn’t have made, but that was part of my journey.”

He remarried in 1982, and Robin gave him another daughter, Eliza, in 1987. But that marriage also ended in divorce, as did a third marriage.

“The thing that I missed was not being there while the kids were growing up,” he says. “But you can’t change it now. They all went on to college, and I am proud of all of them.”

The biggest heartache came on October 4, 2020, when son Ty died of a heart attack at age 53. “That,” Mahan says, “was devastating.”

Somehow, horses have always seen him through. He credits the late horsemen Ray Hunt and Tom Dorrance for helping him understand the nature of the creatures. “I’ve loved them,” he says, “but when I was a young kid, I didn’t know how much there was to love.” His work on the TV show Horse World also exposed him to other equestrian experts. “It was just part of my educational process to get more knowledge and knowledge and knowledge. That’s what I was after.”

Horses also brought Julanne into his life.

In February 2009, Mahan, coming off his third divorce, was taking part in a Cowboys for Christ fundraiser in Ada, Oklahoma. He was on a horse when “a slender, pretty and whip-smart local rancher” rode up to him and said, “I hear they’re going to auction your ass off today. What do you think it’s worth?”

She didn’t bid on him that night for a day of riding, but he invited her to dinner. They were married on his birthday that November. “I didn’t want her to forget my birthday,” he jokes.

“She’s a hand,” Mahan says. “She’s one of a kind. She’s a great rider and totally knowledgeable of horses and cattle. She’s keeping me organized. That’s a 24/7 deal.”

And Julanne, close friends, and horses, he says, are helping him get through his latest challenge.

Last year, a bone marrow biopsy revealed cancer. “That’s a showstopper,” he says.

MD Anderson in Houston was the next stop.

“I kept it quiet,” Mahan says, “so I could process how to handle it emotionally. And I came to the realization that it’s a challenge many people, young and old, have to deal with. And not everybody has horses, not everybody has cattle, not everybody has the lifestyle that we have the opportunity to live. So if I can help somebody, let’s put it out there.”

The cancer was caught before it went into leukemia, and as of May, Mahan’s cancer has been in remission.

“Dealing with horses has really helped me to deal with that situation,” Mahan says. “So, thank you, ponies, and thank you, God, for creating them.”

The Cowboy

The Teton Ridge Entertainment documentary about Larry Mahan sneak-peeks at NFR.

The Cowboy, a documentary from Teton Ridge Entertainment scheduled for a “sneak peek” during the December 1–10 National Finals Rodeo in Las Vegas, isn’t Larry Mahan’s first rodeo, so to speak.

The Great American Cowboy (1973), produced and directed by Kieth Merrill, focused on the 1972 competition between Mahan and 1971 all-around champion Phil Lyne, who won the 1972 title, too. Mahan captured his sixth all-around title in 1973, breaking the record set by Jim Shoulders in 1959. The Great American Cowboy won the Academy Award for documentary in 1974.

The Cowboy tells Mahan’s story, but it’s a different kind of documentary.

“We set out to do something like [2021’s All Madden, about National Football League coach and sports commentator John Madden], kind of a living tribute,” says Joe Loverro, Teton Ridge Entertainment president. “As we started looking across the landscape of characters to talk to, we realized so many of them have their own great stories. So we’re allowing them to tell them. But in doing so, they’re paying tribute to the guy who inspired them.”

Those characters include Ty Murray, whose seventh all-around title in 1998 broke the record set by Mahan and matched by Tom Ferguson in 1979; Bobby DelVecchio, a Bronx native who discovered rodeo in New Jersey at age 14 and later qualified for NFR bull-riding from 1980-1985; and Charles “Charlie” Sampson, the first Black cowboy to win a world championship (bull riding, in 1982).

“Larry has been multigeneration inspiration for so many cowboys from so many different walks of life,” Loverro says. “This is generational … this carryover of the greats, that are all trying to live up to the standards that Larry set. I always describe Larry as the greatest living cowboy. I’ve said that for years — and nobody’s contradicted me.”

The Cowboy’s world premiere is planned for 2023, Loverro says, adding: “We’re shooting for the stars here.”