Come with us to the great state of South Dakota and the legendary state of North Dakota and find out why the natural division might be more east and west.

Homesteaders study me whenever I sit down at my desk. But I’ve never known for sure about the gray faces in that old family photograph: Is that some of my mother’s Norwegian family, who homesteaded in the Red River Valley of what would become North Dakota? Or are they some of my father’s Finnish family, who homesteaded, a few years later and a few miles west, in the James River Valley in what would become South Dakota?

The question has always seemed irrelevant to me because the life they lived was similar; and the things they faced and the stories they told about this place—in Norwegian, in Finnish, in limping English—were pretty much the same.

The "Mighty Mo," Missouri River.

Photography: Courtesy of Travel South Dakota.

I grew up between two border towns. We went to school on the South Dakota side. We went to church and bought tractor parts on the North Dakota side. There wasn’t a lot of difference. For the big secret about the Dakotas, as many residents will tell you, is that they have more in common north and south than they do east and west. I grew up hearing my father say Dakota should have been one state—or if they were determined to cut it in half, an East Dakota/West Dakota split would have made more sense in 1889. It’s simple geography.

“The Dakotas are spliced down the middle by the 100th meridian, which roughly approximates where the Missouri River bisects the states,” says Jon Lauck, a historian who works for South Dakota Sen. John Thune. “East of the line, the Dakotas have a Midwestern/Iowa-type orientation, and west of the line, the Dakotas tend to be Wyoming-ish. You can see it in the land and the crops and the people.”

Especially in South Dakota, which is entirely cut in half by the river, people in the Dakotas use the terms East River and West River to refer to those distinctly different regions and identities, Lauck says.

The Dakotas are spliced down the middle by the 100th meridian, which roughly approximates where the Missouri River bisects the states."

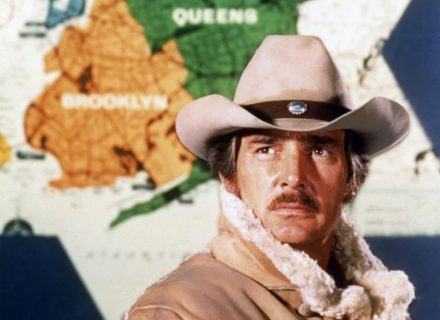

The deep cultural differences make for countless jibes back and forth. One story, quite likely true, has it that the great Casey Tibbs, already famous as the greatest bronc rider in history, was greeted in a bar in Fort Pierre, Casey’s hometown, by someone who seemed to know him. Casey, a West River cowboy from the rugged Mission Ridge country, was happy to visit, even though the conversation took place in the bathroom of the bar. After the stranger left, one of Casey’s real acquaintances asked him, “Who was that?” Casey said: “I have no idea. He was from East River, though.” “How do you know that?” “He washed his hands.”

The Sitting Bull Monument stands in a remote spot on SD Highway 1806, two miles southwest of Mobridge, overlooking the Missouri River; the monument was sculpted by Korczak Ziolkowski, who is known for the Crazy Horse Memorial in the Black Hills.

South Dakota-grown Tony Bender—a columnist for 30 years for newspapers in both Dakotas, Minnesota, and Montana—agrees that the north-south differences are harder to find. “The biggest differences are marked by the divide of the Missouri River,” says Bender, who lives in North Dakota. “To the east, it’s agrarian with plenty of cattle. West River, especially in North Dakota, is a different world. It’s authentic cowboy country. Less hospitable to grain farming and heavier on cattle. More driven by a cowboy culture than ethnicity.

“In the east, you find strong German and Scandinavian roots and culture. You can still hear German spoken in the small-town cafes—especially if they’re talking about a stranger in town. That’s waned, though, in recent decades.

North or south of the line, we all honored people like Casey Tibbs. He’s the main attraction at the Casey Tibbs South Dakota Rodeo Center in Fort Pierre. We had the same heroes in both Dakotas and the same outlaws—like the North Dakota-born wolf Old Three Toes, who preyed on sheep and cattle in both Dakotas from 1912 until 1925, when a government trapper finally caught him near Buffalo, South Dakota.

As for our heroes, we tend to carve them into mountain faces. Mount Rushmore was the vision of Doane Robinson, the aging state historian of South Dakota. To realize his dream of a mountain memorial so massive it would put the state on the map, he contacted sculptor Gutzon Borglum for his artistic prowess and gained the support of Sen. Peter Norbeck for his political clout. Robinson originally imagined memorializing Western figures such as Chief Red Cloud, Buffalo Bill Cody, Lewis and Clark, and legendary Sioux warriors like Crazy Horse. But Gutzon decided on four U.S. presidents.

South Dakota has a particular fondness for honoring U.S. presidents: Rapid City put statues of the presidents along streets throughout its downtown and calls itself “the City of Presidents.” Perhaps we have a special debt to Thomas Jefferson for arranging the Louisiana Purchase, which included the western lands that would become the Dakotas and other states. But the most fitting of the four Borglum chose would have to be Theodore Roosevelt.

More than any other president, Roosevelt belongs to the West. He was a rancher near what is now the North Dakota town of Medora, and he was emphatic about how crucial his experience there was in putting the finish on his character. Bigger than life, Roosevelt the rancher, Roosevelt the Rough Rider, is a key figure in North Dakota’s tourism campaign to brand the state “legendary.” As Doug Ellison of Western Edge Books in Medora told me, Roosevelt consistently referred to his ranching days as pivotal and said several times that he would never have become president but for that experience. “Here the romance of my life began,” Roosevelt said when he visited Medora on September 16, 1900, stumping for the McKinley-Roosevelt ticket. “I had studied a lot about men and things before I saw you fellows, but it was only when I came out here that I began to know anything, or to measure men right.”

Mount Rushmore National Memorial, South Dakota.

Mount Rushmore National Memorial, South Dakota.

When I was a teenager, I remember musing about which presidents were memorialized on Mount Rushmore and puzzling over Theodore Roosevelt—did he really belong there on the side of that mountain? My father, a farmer who read history all winter when he couldn’t be in the field, told me Roosevelt might be the president who most belongs up there because he had lived out west and he had done so much for conservation and national parks. He had established our own Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota, for example.

There’s a project in the works to build the Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library in the rugged North Dakota landscape he loved, and its backers say their intent is to show “what we can learn from, not about, our 26th president.” What makes the project brilliant is the location. Only in southwestern North Dakota will people be able to learn something vital about Theodore Roosevelt, because it’s not in the history books. It’s in the land.

However important those presidents are in American history, memorializing white men in the Black Hills called for an Indigenous answer. In the late 1930s, Chief Henry Standing Bear of the Lakota wrote to sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski, who had once been chosen by Borglum to work with him on the carving of Mount Rushmore: “My fellow chiefs and I would like the white man to know the red man has great heroes, too,” the chief explained, and Ziolkowski began to work on an idea for a counterpart: Crazy Horse. When the sculptor died 1982, his wife took over, and on her death in 2014, family members carried on.

When the memorial is ultimately completed, the Black Hills-born Oglala Lakota warrior will appear to charge right out of the mountain, his likeness based solely on descriptions because he refused to have his picture taken. According to the Crazy Horse Memorial Foundation, the great carving is meant to honor all the Indigenous people of North America. Crazy Horse will be “riding his steed out of the granite of the sacred Black Hills with his left hand gesturing forward in response to the derisive question asked by a cavalry man, ‘Where are your lands now?’ Crazy Horse replied, ‘My lands are where my dead lie buried.’”

The focal point of a large university campus and cultural complex celebrating the Native Americans of North America, the memorial immortalizing Crazy Horse is so massive it could contain all four heads of Mount Rushmore.

Like much of the history and culture of the Dakotas, these statements in stone transcend state lines and borders and speak to the West and the nation.

Photography: Courtesy of Travel South Dakota, Michelle Shining Elk, North Dakota Tourism.

Find out more about visiting South Dakota at travelsouthdakota.com and North Dakota at ndtourism.com.

From our July 2022 issue.