From 1947 to his death in 1983, Yanktonai Dakota artist Oscar Howe has shaped the world of traditional Native American artwork through his breathtaking work.

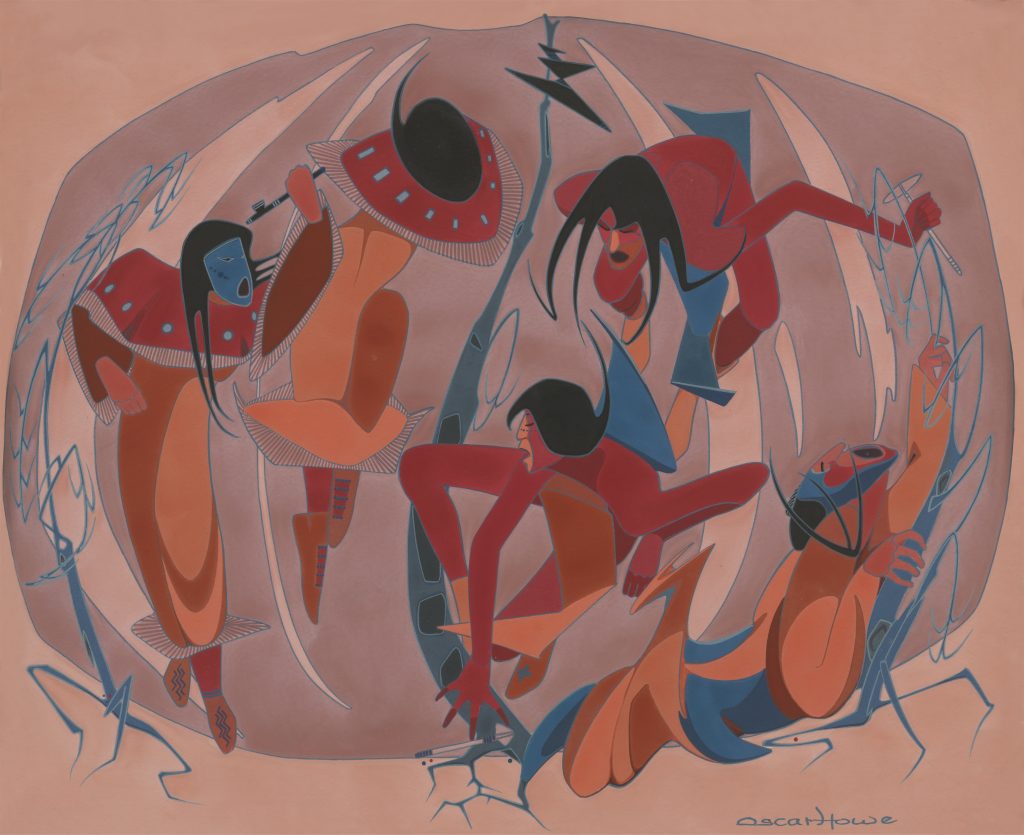

In 1958, a Yanktonai Dakota artist from South Dakota entered a painting called Umine Wacipi: War and Peace Dance in the Philbrook Art Center’s annual juried Contemporary American Indian Painting Competition (later called the American Indian Exhibition, or simply, The Indian Annual) in Tulsa. Oscar Howe had done well repeatedly at the show in the past, taking home Grand Purchase awards in 1947, 1954, 1959, 1962, and 1963, and winning first and second place for his entries in 1949, 1950, 1952, 1953, 1956, 1960, and 1965.

In 1958, though, the judges decided that while the painting could remain in the exhibition, it would not be considered for a prize. Their reason? This new painting was “a fine painting—but not Indian.” What followed was a watershed moment as Howe fired off a letter to the Philbrook.

“Who ever said … that my paintings are not in the traditional Indian style has poor knowledge of Indian Art indeed,” Howe wrote in a text that still echoes in the Native American art world. “Are we to be held back forever with one phase of Indian painting … with no right for individualism, dictated to as the Indian always has been, put on reservations and treated like a child and only the White Man know what is best for him … Now, even in Art, ‘You little child do what we think is best for you, nothing different.’ Well, I am not going to stand for it. …”

Umine Dance, 1958. Casein and gouache on paper, mounted to board, 18 x 22 inches.

Umine Dance, 1958. Casein and gouache on paper, mounted to board, 18 x 22 inches.

Photography: Courtesy of the National Museum of the American Indian and the Oscar Howe Family.

Born in 1915 on the Crow Creek Indian Reservation in central South Dakota, Howe drew avidly as a student at Pierre Indian School, a boarding school. Afterward, he studied at Santa Fe Indian School in New Mexico, later earning degrees from Dakota Wesleyan University and the University of Oklahoma. He taught art for nearly a quarter of a century at the University of South Dakota before his death in 1983.

Howe’s stand for artistic freedom in Native American art would be reason enough to remember him. But his art is also remarkable, as viewers will see in a fascinating retrospective exhibition on view in New York City then Portland, Oregon. Dakota Modern: The Art of Oscar Howe follows the Plains artist’s career through more than 40 years, from conventional work he did in high school in the 1930s to his more innovative and abstract work of the 1950s and 1960s.

“People are blown away when they see his paintings for the first time,” says exhibition curator Kathleen Ash-Milby of the Portland Art Museum. “Howe’s an icon. He’s like the grandfather of contemporary Native American art. But he’s not very well-known outside a very limited number of people. We don’t want him to fall into obscurity.”

Were that to happen, it wouldn’t just be a shame—it would be a gaping oversight in art history. That 1958 incident wasn’t just immensely important to Howe personally, it was significant to other artists. “His making a stand and writing that letter was a catalyst for change that was already growing in the Native art community,” Ash-Milby says. “There was internal dissent brewing about what artists ‘should’ be doing.”

Throughout his career, Howe’s work was, with very few exceptions, representational. “Historically in many Plains cultures, men were the ones who created representational work—work that was very literally representing a person, or an event, an animal, a thing,” Ash-Milby says. “Howe began to create work that was much more abstract but maintained that representational aspect. So even though an image might look initially like this whirl of color and different planes, geometric shapes, it’s a dancer, for example, or it’s a buffalo, or it’s a rider on a horse."

Art critics sometimes used terms such as cubist or neocubist to describe Howe’s later works. But he pushed back strongly against the idea that his art was simply derivative.

“I don’t think you can deny that he was influenced by modern art, by modernism,” Ash-Milby says. “He had a very complete education in Western art history. His degrees were in the Western art traditions, and he was teaching Western art history.” In graduate school, she adds, he was influenced by movements such as surrealism and by Mexican modernism. “[He] drew his inspiration from multiple sources, especially Dakota pictorial traditions, aesthetics, and philosophies, to come up with something that was really, truly his own.”

Oglala Lakota artist Donald Montileaux, who studied with Howe and considered him a friend and mentor, says Howe’s work still looks fresh and new—and grounded in the Plains. “You can walk out on the prairie any time and look up at the sun, the rising and the setting, and see Oscar’s movement up there in the clouds, and the colors as well,” Montileaux says. “You could put Oscar’s works in any art show today, and it would win first, second, third—undoubtedly. He was in a totally different class than anybody doing artwork today.”

Onktomi and Ducks, No. 2, 1976. Casein on paper, 19 5/8 x 24 1/2 inches.

Onktomi and Ducks, No. 2, 1976. Casein on paper, 19 5/8 x 24 1/2 inches.

Photography: Courtesy of University Art Galleries, University of South Dakota, PC OH 23 (O.H. 79.002)

Dakota Modern: The Art of Oscar Howe is on view through September 11 at the National Museum of the American Indian in New York; November 4, 2022 – May 12, 2023 at Portland Art Museum in Portland, Oregon; and June 10 – September 17, 2023 at South Dakota Art Museum at South Dakota State University in Brookings. An accompanying catalog is available. You can also see the artists's work at the Oscar Howe Gallery at the University of South Dakota in Vermillion, which is the primary lender to the Dakota Modern show and where Howe's strong legacy includes his teaching career and the largest collection of his art. See more and learn more at the Howe Gallery at Dakota Discovery Museum in Mitchell, South Dakota, and at the Aktá Lakota Museum & Cultural Center (an outreach of St. Joseph’s Indian School) in Chamberlain, South Dakota. americanindian.si.edu, portlandartmuseum.org, sdstate.edu/south-dakota-art-museum, usdartgalleries.com, dakotadiscovery.com, aktalakota.stjo.org.