Roman Loranc and Christopher Burkett are two important contemporary fine-art photographers represented by one of the country’s most influential galleries.

If you’ve ever been to Carmel and Monterey, California, you know why Clint Eastwood set up shop there. It’s not just fantastic for celebrity golfers who like Pacific Ocean views with their putts. The area has long been revered by photographers, too, for its inspiring beauty, its light, its creative atmosphere — and for a certain seminal gallery that has supported their careers and the medium itself.

“Film photography was the most important art medium of the 20th century,” says Carol E. Williams, owner and founder of Photography West Gallery in Carmel-by-the-Sea. “It has a tremendous amount to convey that no other artistic process can. It is such a highly sensitive medium that you can imagine you see something and have it mysteriously materialize in the final image. Film captures the world behind the world. When you’re eating good food, you want to get as close to the source as you can; in photography, that source is light. And light has something to say — it’s a dialogue between heaven and earth at its best. I have found photography to be a very spiritual art medium and because of that, it has tremendous visual range and an utterly unique artistic dimension.”

As a photographer herself, Williams would know. Her perspective comes from behind the lens and inside the gallery — decades of spreading the gospel of fine-art photography at Photography West, which celebrated 40 years in 2020.

It’s not even 8 a.m. in California and Williams’ daughter, Julia Christopher, is already off to a light-filled, picture-perfect day — and not just because she lives in a picture-perfect place. Christopher is the director of Photography West Gallery, one of the only — if not the only — galleries in the U.S. that exclusively show wet-process photography.

“Carol Williams — who is the gallery’s founder and my mother — was one of the first single women in the U.S. to be approved for an SBA startup loan,” says Christopher.

Five hundred people showed up at the opening in 1980. “The gallery was originally envisioned as a regional cooperative founded to support contemporary local photographers, which just happened to include masters like Ansel Adams and Brett Weston, both of whom attended our opening. Ruth Bernhard was also alive and working, and we genuinely wanted to support her and other living photographers. We never showcased 19th-century photographers for that reason, with two exceptions: Edward Weston and Imogen Cunningham, who were founding members of [the famed photography collective] Group f/64 and too important to the history of photography in the area to exclude. We wanted to support their families as well.”

In the photography world, these are some serious bona fides and the names are as big as they get.

Going into the family business as the gallery’s director was a natural choice for Julia Christopher. Immersed in images and surrounded by the upper echelons of photographers and emerging talents when she was growing up, she really didn’t need persuading that photography was indeed an art.

“The argument that convinced me that photography is a fine-art medium — an argument I still use — is that when you’re working in a darkroom with film, blind in the dark, it’s physically impossible to make the same one twice,” Christopher says. She likes to use the illustration of her mother showing 10 originals of Ansel Adams’ Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico, 1941. “Carol would line them up so clients could see differences between each one.”

Not only is there a discernible difference from one to another that makes each photograph unique, they are also of an entirely different medium from digital. “I love all art mediums and have the utmost respect for contemporary digital art and graphics design, but digital is as different from photography as oil [on canvas] is from pastel,” Christopher says. “Photography means ‘writing or drawing with light’ — literally. In order for an artwork to be a photograph, it must be made with light, just like a painting is made with paint, not a pigment printer.”

Christopher is careful to emphasize the distinction between the two mediums lest photography become a lost art.

“I once had a college student come in the gallery and ask me which Instagram filter Christopher Burkett used,” she says. “At first, I laughed and thought it was a joke. When I realized she was being serious, I attempted to describe film and the darkroom process, watched her eyes glaze over, and she left. Shortly thereafter, a man came into the gallery and asked if I was OK — my facial expression apparently spoke volumes. I explained what had just happened, and he said, ‘You’re absolutely right — there’s a whole generation that has no idea what photography is and thinks it’s something you do with a phone.’”

It’s not that Christopher thinks there’s anything wrong with digital: “I love taking pictures, especially video, with my iPhone and couldn’t live without it,” she says. But for Christopher, Williams, and the photographers they represent at Photography West Gallery, it has always been and will always be about original photographs handmade by the artists from film using light, light-sensitive papers, and chemistry.

We talked with Christopher and Williams about two outstanding contemporary photographers, Roman Loranc and Christopher Burkett.

Cowboys & Indians: Talk to us a bit about the gallery and the two photographers you’ve chosen to highlight.

Julia Christopher: Being a gallery founded and managed by photographers, we know — firsthand — how difficult it can be to receive feedback, let alone representation, from galleries. In turn, we always promised to give complimentary in-person portfolio reviews to photographers who met our prerequisites: 1) use medium- and/or large-format film and 2) do all developing and darkroom work by hand without any computers, professional labs, or third-party assistance. Both Christopher Burkett and Roman Loranc were unknown, unrepresented photographers when they walked into Photography West — Burkett in 1984 and Loranc in 1997 — and after reviewing their portfolios, we decided to give them an opportunity to reach an art-buying audience.

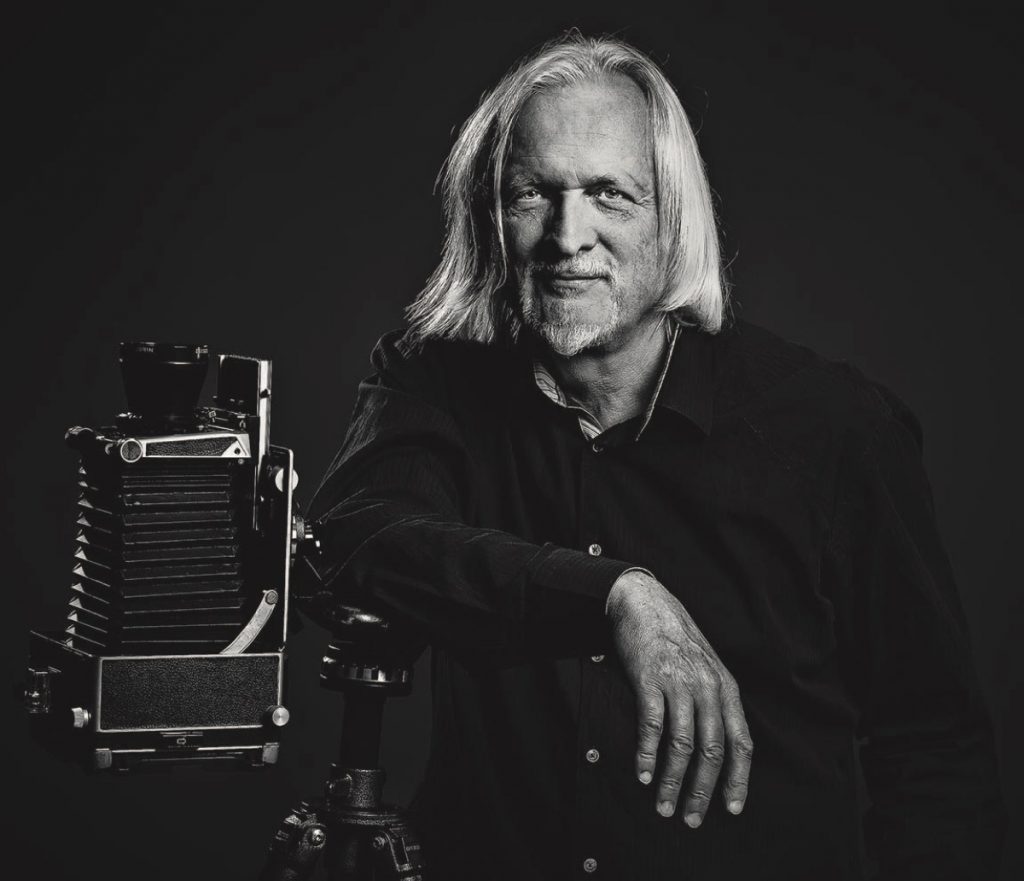

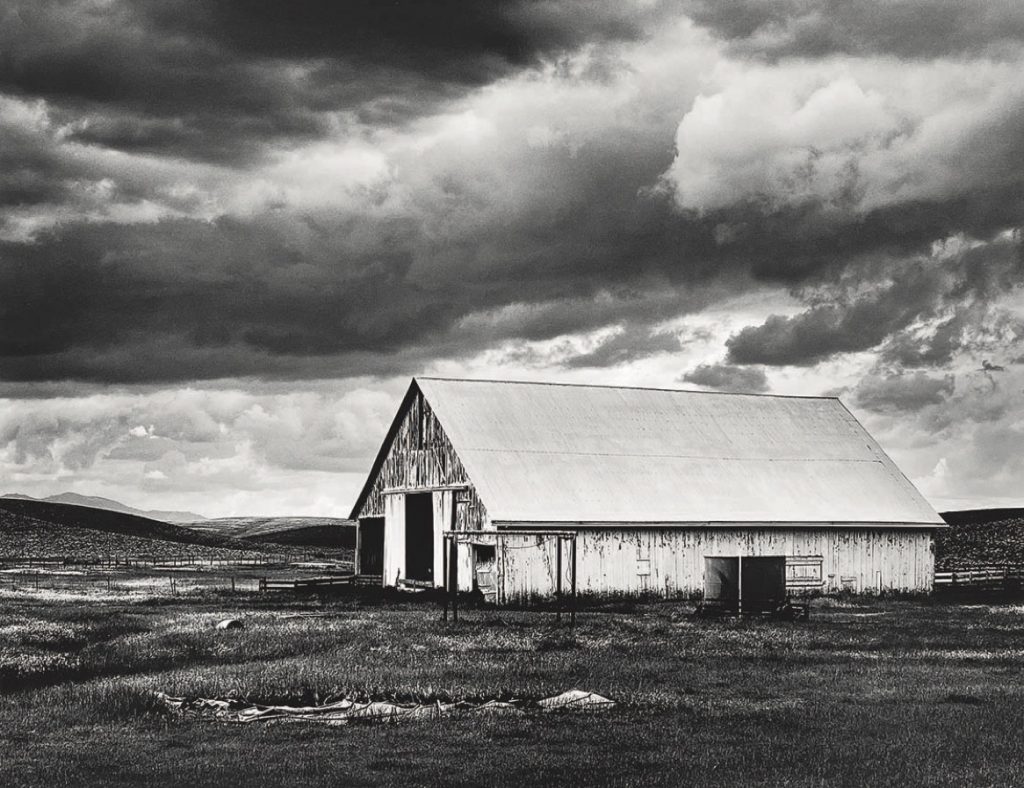

Roman Loranc

Roman Loranc was born in Poland in 1956 and came to the U.S. in 1982. After settling in California’s Central Valley, he dedicated himself to photography and capturing the vanishing subjects surrounding him, especially the fragile wetlands shadowing the Pacific Flyway, the rugged Diablo Range, and the area’s once-mighty rivers.

C&I: Tell us more about Roman Loranc.

Carol Williams: Roman Loranc is one of the most important landscape photographers on the West Coast and has turned his large view camera on the vanishing wetlands, contributing to an important and ongoing legacy of California wilderness photography.

Julia Christopher: When people come into the gallery and ask, “Why is photography fine art?” I respond by showing them a series of Roman Loranc photographs side by side. While his beautiful photographs are clearly distinctive and unique from a compositional standpoint, he also happens to be the only gallery artist who makes no effort to be consistent in the darkroom. It is physically impossible to create the same exact gelatin silver photograph twice from the same negative, but most artists will make some effort to be consistent. Roman, however, intentionally tones them differently (using a combination of sepia and/or selenium chemical toners), often crops them differently, dodges and burns each one differently. And that is why I always tell clients, “If you see a Loranc in the gallery you love, buy that particular piece, because it’s a one-of-a-kind work and he’ll never be able to make another one quite like it.”

Click on the slideshow for more images

Loranc’s photographs are truly unique. In addition, his invaluable contribution to the history of photography is that he expanded the West Coast photographic tradition to include California’s Central Valley, which is an area no one had extensively photographed before. His most famous photograph, Private Road With Clouds, was taken in the Central Valley, and I’ve had multiple clients exclaim, “It reminds me of home!” I’ve found that no matter where someone is from in the Southern or Western United States — Texas, Oklahoma, Wyoming, New Mexico, California, etc. — Private Road resonates with them. It has a nostalgic, yet inspiring and optimistic, quality about it that looks toward the future — almost like a visual representation of the American dream.

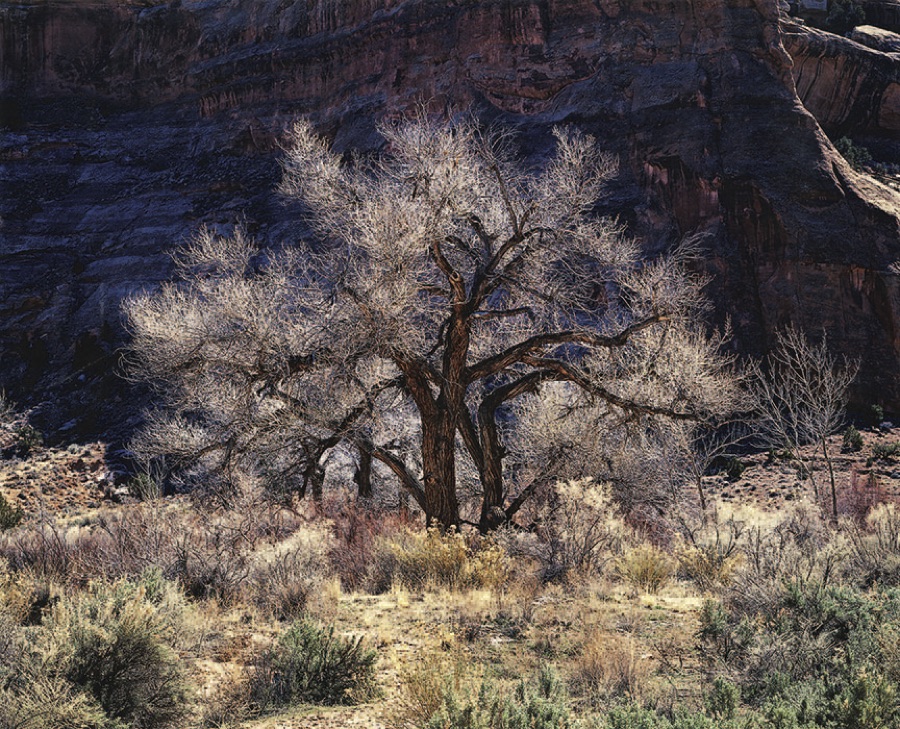

Christopher Burkett

Christopher Burkett grew up in the Pacific Northwest and entered a monastic religious order at age 19, leaving it in 1979 to pursue the Divine through nature photography. Born in 1951 and severely nearsighted as a young child, he literally began to see differently after getting glasses at age 6 and discovering a physical world brimming with miraculous minute detail. Now living in Oregon, Burkett continues to use color photography and meticulous printing techniques to capture Creation’s light-filled landscapes.

C&I: What more can you tell us about Christopher Burkett?

Carol Williams: Christopher Burkett is the most outstanding color photographer in America today because he combines an unerring sophisticated sense of composition with his own innate mystical vision, while still creating each photograph by hand using traditional darkroom materials that offer the sharpest resolution possible; his technical genius results in finished Cibachromes that are second to none.

Julia Christopher: You do not “view” a Christopher Burkett photograph in person — you experience it. The goal of his work is not simply to take a beautiful photograph. The goal of Burkett’s work is to come as close as humanly possible to re-creating the physical experience of being in nature with as much integrity as possible.

Click on the slideshow for more images

After experimenting with every photographic process and material, Burkett felt the particular combination of Fuji Velvia 50 and Provia 100f film with now-discontinued Cibachrome photographic paper was the “truest to life,” and I almost exclusively display his larger sized — 30 by 30 inches to 40 by 50 inches — Cibachromes in the gallery to enhance the “lifelike” experience. He also refuses to use any filters on his cameras when he’s photographing to avoid any unnecessary distortion. People often walk in the gallery and ask me if Burkett’s photographs are paintings, because “they’re so three-dimensional!”

In addition to his work having a painterly three-dimensional quality, Burkett also has a painter’s eye. My personal favorite Burkett photograph is an incredibly simple subject, but the composition is profoundly abstract and I never put a wall tag on it, because I love hearing visitors guess what it is. Sometimes they’re 100 percent convinced “it’s the sunset on the ocean,” or perhaps “it’s an aerial photograph of people on a beach,” or “an Aboriginal painting,” or “it looks exactly like huts on the shore of Thailand.” I even had a dermatologist insist it looked like epithelial cells under a microscope! A client who purchased one of the 30 by 30-inch Cibachromes told me it was the best art purchase he ever made and the focal point of every conversation at his dinner parties. The title of the photograph is Clearwater River Ripples (Idaho). Only Christopher Burkett could turn a simple riverbed in Idaho into such a sophisticated work of art. The fact that Burkett’s original Cibachromes are now also considered historical artifacts is simply an added bonus for any art collector.

He is one of two people in the world that I personally know of who are currently working with this material. The machine that manufactured it has been dismantled, the paper discontinued. It is a historical process now. PBS aired a beautiful NewsHour segment about Christopher, showing and explaining his process, which you can watch on their website or on YouTube.

C&I: Thank you for introducing us to the wonderful work of Christopher Burkett and Roman Loranc. Any parting thoughts about photography?

Julia Christopher: Photography is a fascinating, truly magical art medium. Christopher Burkett always says, “Photography is about extraordinary moments of light,” and it is my privilege to share that light with others. Every time I walk in the gallery I’m awestruck by the depth and luminosity of each photograph. The silver and metals in the different photographic papers (gelatin silver, Cibachrome, platinum palladium, cyanotype, etc.) inherently refract light and they literally glow on the walls. I also love discovering the differences between each photograph made from the same piece of film. I often describe film as a painter’s “sketch” or “study” for a painting — the sketch is not the painting; the artwork the artist makes from the sketch is the painting, and no two paintings made from the same study are ever exactly alike. For me, the unique way an artist chooses to interpret film in the darkroom is the “fine art” of photography. As Ansel Adams said, “You don’t take a photograph, you make it.”

Collectors Note: Although both artists have sold rare photographs for $40,000, Roman Loranc’s prices generally average $2,000 – $10,000. Private Road is $5,000 for an 11 x 14 inch and $40,000 for a 30 x 40-inch gelatin silver. Christopher Burkett’s Cibachromes start at $1,250. Most are $1,250 for a 20 x 20/20 x 24 inch, $2,500 for a 30 x 30/30 x 40 inch; museum editions start at $6,000; however, Clearwater River Ripples is $3,000 for a 20 x 20 inch and $6,000 for a 30 x 30 inch (it’s sold out in the 40 x 40-inch size).

Photography West Gallery is open daily by appointment and Saturday and Sunday 11 – 4. 1 Dolores St. SE of Ocean Avenue, Carmel-by-the-Sea, California, 831.625.1587.

Photography: Portrait of Roman Loranc by Reinhold Kager, portrait of Christopher Burkett by Bill Purcell

From our February/March 2021 issue.