We join executive director Seth Hopkins for an exclusive tour of the award-winning Booth Western Art Museum.

Where do you find the best art museum in the country? Not just the best Western museum — the best art museum, period. New York, Chicago, L.A.? It might surprise you to learn that in the recent USA Today 10Best Readers’ Choice Awards the Booth Western Art Museum in Cartersville, Georgia, ranked No. 1.

The Booth was nominated alongside such prestigious museums as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Chicago Art Institute, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. “For us to beat out so many well-known museums is amazing. Nationally we are probably the least-known museum on the entire list, so it’s a win that is kind of like slaying 19 Goliaths all at the same time,” says Booth Museum executive director Seth Hopkins.

The award comes just as the Booth Museum is celebrating the 20th anniversary of its founding by an anonymous local family in July 2000. The museum has welcomed almost a million visitors since it opened in 2003 and became an affiliate of the Smithsonian Institution.

You’ll find the 120,000-square-foot museum just north of Atlanta in the historic town of Cartersville. Its collection includes significant historic works and major examples of the best of living artists, those working in historical realism and those on the cutting edge of the more contemporary art of the West. “It’s a great overview of what has been going on in Western art over the past 50 to 60 years,” Hopkins says. Visitors are invited to “See America’s Story” through contemporary Western artwork, a Presidential Gallery, a Civil War art gallery, and an interactive children’s gallery called Sagebrush Ranch.

“We hope Western fans from around the world will come and enjoy what we’ve created and find out why we were recognized as one of the great art museums in America,” Hopkins says. In the meantime, we’ve asked Hopkins to give C&I readers an exclusive tour highlighting a dozen of the most beloved pieces in the Booth’s collection.

Deborah Copenhaver Fellows, Giving Thanks, 2006

American, born 1948

Bronze, 156 x 51 x 138 inches

The first piece you see when you walk onto our manicured grounds is this monumental bronze by Deborah Copenhaver Fellows. She is Western royalty: the daughter of legendary bronc rider Deb Copenhaver, the sister of former world champion roper Jeff Copenhaver, and the wife of multi-award-winning Cowboy Artist Fred Fellows. Yet she has established her own formidable identity in the art world through a wide variety of bronze creations that run the emotional gamut from evoking belly laughs to jerking tears. She has sculpted several war memorials and is currently working on a sculpture to honor the 19 Granite Mountain Hotshots killed in the deadly Yarnell Hill Fire in Arizona in 2013.

One of the great thrills of my career was being present for the unveiling of Fellows’ depiction of Barry Goldwater for Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol.

And I experience a quiet thrill whenever I pass this meditative bronze as I approach the museum entryway. The sculpture depicts a cowboy on horseback, hat off, head bowed. It honors Fellows’ father through her most vivid childhood memories, when he was a rodeo producer and would be the last to ride into the arena during the grand entry. A spotlight would hit him and he would pray for the safety of the cowboys and cowgirls as well as the stock.

The full title of the bronze is Giving Thanks for the Rain, the Grass and a Way of Life. Its powerful message is amplified by its placement near the cornerstone for a church that formerly occupied the museum site. The original church building had grown too small for the congregation and had significant asbestos issues. The anonymous founders of the Booth reached a more than fair deal with the church, allowing them to move to a larger piece of land and grow, just like the metaphorical grass referred to in the title of the bronze.

Harry Jackson, The Range Burial, 1958

American, 1924 – 2011

Bronze, 16 x 22 x 44 inches

As we enter the building, we are greeted by two major murals on long-term loan from the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, created by Harry Jackson, who is much better known as a sculptor. Looking more closely you will indeed see each mural has a corresponding bronze sculpture in front of it. The rest of the story in a moment, but first let’s go back in time to 1999, when we were all worried about Y2K. My Y2K moment was when the founder of the Booth, for whom I had worked for 10 years, walked in my office to inform me that he was selling his company, planned to build an art museum, and that I would be running it. At that point I had little art background and no museum experience, but he told me to take advantage of the two to three years it would take to build the building to get out and learn something about Western art.

We took regular trips to museums, galleries, artists’ studios, auctions, and elsewhere to gather art and ideas as part of my crash course in art appreciation. One of the first stops we made was at the [R.M.] Norton Art Gallery in Shreveport, Louisiana. It was there that I first encountered this sculpture, The Range Burial. It stopped me in my tracks and gave me a powerful emotional jolt as I stood transfixed. Having had relatively few art encounters, it was a new and strange feeling for me. I wondered how often it happens to people in the art world. For me personally, it’s happened maybe 15 times in the last 20 years.

When a cast of The Range Burial came up for auction, it was one of the few times I’ve overstated my case to the board that we must own this piece. Luckily, it did not sell for anywhere near what it should have been worth. Jackson had originally created the bronze as a way to work out the figure group for the mural, and did the same with the corresponding bronze and mural called The Stampede. Shortly after our acquisition we found out the murals might be available for loan. The artist’s last public appearance before his death in 2011 was at the unveiling at the Booth in 2009.

John Coleman, Caitlin/Bodmer Series, 2004 – 2011

American, born 1949

Bronze, dimensions vary (average 34 inches high)

Two of the first works you see on entering our permanent collection galleries are paintings from the 1830s by George Caitlin. Owned by the Smithsonian American Art Museum, we’ve had them on long-term loan for many years. They constitute one of the art historical bookends in our galleries; the other is this series of 10 bronzes created by John Coleman over a seven-year period. Coleman studied all the information he could find on the works of Caitlin and one of his contemporaries, the Swiss artist Karl Bodmer. Scouring their paintings, sketches, and descriptions, Coleman sought to determine the 10 most interesting-looking individuals they ever encountered — not the most powerful chiefs or the most well-known, but the most distinctive physically. In some cases Lewis and Clark had met the same individuals as young men and also commented on their appearance.

In our opinion, this series represents one of the greatest achievements in Western sculpture since the death of Remington in 1909. The combination of historical research, attention to detail, compositions, and the power of all 10 being presented together as they are displayed at the Booth gives the group a very strong presence.

W.R. Leigh, Dangerous Trail, 1914

American, 1866 – 1955

Oil on canvas, 60 x 40 inches

While the Booth Museum seeks to mainly collect the best living artists working in the Western genre, we have also acquired some important pieces from the historic period to lend depth to the collection and add context to the work of the living artists we highlight. One of the more important works in the collection is this action scene set in a canyon, called Dangerous Trail by William Robinson Leigh, also known as W.R. In his book about his travels in the West, Leigh mentions this type of accident happening with some regularity, and once a horse was unloaded they would often upright themselves and be no worse for wear. This expedition now seems doomed though, since the coffee pot is long gone.

Leigh was known in his lifetime as the Sagebrush Rembrandt. A West Virginian by birth, he was both a painter and illustrator. He is best known for his paintings of the Grand Canyon and Yellowstone National Park, as well as the Hopi and Navajo Indians, who were among his favorite subjects. He was a contemporary of Remington and Russell, yet he is not nearly as well known to the public. My theory is that he actually lived too long — not passing until 1955 at the age of 89 — and that he was hardly mentioned in the early books on Western art introduced in the 1950s because he was either still alive or had only recently passed.

Maynard Dixon, Red Butte With Mountain Men, 1935

American, 1875 – 1946

Oil on canvas, 96 x 214 inches

In the largest of the permanent collection galleries, we are nearly overwhelmed by the presence of Red Butte With Mountain Men, an 8-by-18-foot painting by Maynard Dixon. He created two murals this size in 1935 for a restaurant in San Francisco called the Kit Carson Grill. This gives us a clue as to who these men might be, perhaps the legendary scout Kit Carson leading a pack train through southern Utah (the artist maintained a home and studio there in Mount Carmel). This rock formation has never been identified as any specific place; rather it seems to have sprung from Dixon’s mind, having natural geologic features fused with elements of cubism. The companion painting, a horseback portrait of Carson, has been on long-term loan to Scottsdale’s Museum of the West for many years.

Dixon is one of the few artists who could attract the attention of both Western collectors and those seeking modernism, thus driving his importance in both art history and at auction ever higher. He is also a hero for a legion of artists in the contemporary generation who idolize his work and seek to emulate it to one degree or another.

Ed Dwight, Dirt Farmers, 1980

American, born 1933

Bronze, 22 x 14 x 8 inches

One of the goals of the Booth Western Art Museum is to convey the idea that the history of the American West is not just white guys, on white horses, with white hats; rather, that it was a very diverse environment where people were so few and far between they had no choice but to rely on each other despite thoughts of discrimination. In our collections we have works by Native Americans, African Americans, Chinese Americans, and many more works by women artists than in most other Western museums. That is not to say we’re better: It has more to do with our collection being newer and more closely reflecting the diversity of artists and subjects found in the contemporary Western art scene versus 100 or more years ago.

Ed Dwight was the first black astronaut candidate. If JFK had lived to serve two full terms, Dwight may well have walked on the moon. But after Kennedy’s death, President Lyndon B. Johnson asked him to step down to make way for his own black candidate; Dwight resigned from the Air Force several years later. An engineer, he had successful careers as a land developer and restaurateur before he took up sculpture relatively late in life. He has gone on to create well over 100 monuments and more than 18,000 smaller-scale bronze gallery pieces. This particular work is based on his grandparents from Dalton, Georgia, former slaves who went west and homesteaded in Kansas City, Kansas. The Booth was introduced to this work when a cast was loaned to an exhibition we organized called The Black West: Black Cowboys, Buffalo Soldiers, and Untold Stories. Following that show, we acquired a number of pieces that now allow us to tell those stories that had gone untold for too long.

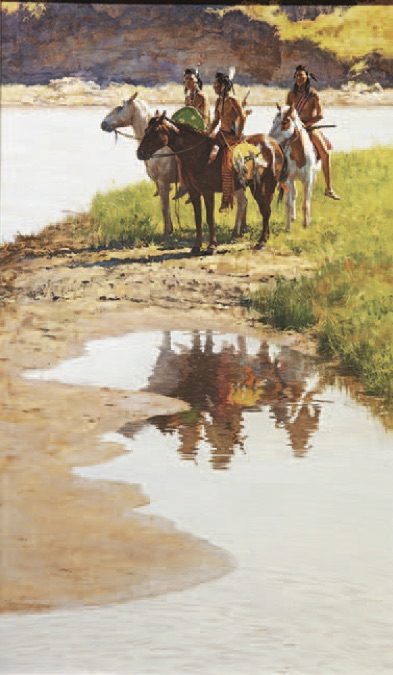

Howard Terpning, River Crow, 2000

American, born 1927

Gouache on paper, 40 x 24 inches

As we enter the First Peoples Gallery, honoring Native Americans, we encounter many works by the most well-known Western artists of the previous 50 years: G. Harvey, Joe Beeler, Roy Anderson, Ken Riley, and at 65, the relative youngster Martin Grelle. At one end of the gallery are three works by Howard Terpning, the most awarded and highly prized artist of this generation. A native Chicagoan, Terpning became enamored of the West and Native Americans at age 15 when he camped and fished with a cousin for a summer near Durango, Colorado. He served as a U.S. Marine during peacetime but developed some of his empathy for Native peoples while serving as a civilian combat artist in Vietnam.

The three Terpning pieces — River Crow (gouache), Trail Along the Backbone (oil), and On the Brink (charcoal and acrylic) — cover 15 years of his career in three different media; it’s a unique installation and one we’re lucky to have. River Crow depicts tribal members of a subgroup of the Crow Nation, and their reflections in the water are a double entendre of the title. Terpning’s use of gouache in this painting harks back to the days when he was a young illustrator working in the studio Haddon Sundbloom and his subsequent career as an incredibly successful movie poster artist. (Terpning’s images for Gone With the Wind and The Sound of Music are two of the most remembered in movie history.) He used this opaque water-based medium to achieve the look of oil with the immediacy and quick-drying quality of watercolor.

Martin Grelle, Running With the Elk Dogs, 2007

American, born 1954

Oil on linen, 48 x 60 inches

The Booth Museum recently recognized Martin Grelle with its Artist of Excellence Award. This is only the second time the museum has awarded this prize, the other honoree being sculptor John Coleman last year. Previously the museum had honored artists such as Howard Terpning and Glenna Goodacre with lifetime achievement awards. Several years ago the decision was made to focus on midcareer artists rather than those who might be nearer the end of their career.

A longtime member of the prestigious Cowboy Artists of America, the much-awarded Grelle hails from Clifton, Texas, where he continues to live on a ranch in Bosque County, an area settled by hardworking Norwegian and German immigrants and now home to several other important Western artists.

This painting by Grelle is somewhat atypical, not featuring water nor a mountainous landscape. Instead the action is set on the featureless prairies, where the Plains Indians got their first look at wild horses. Legend suggests the Blackfeet described the first horses they saw as looking somewhat like elk, being about the same size and color, while others thought of them as bigger versions of dogs that were used to pull the travois loaded with their belongings, so they called them elk-dogs.

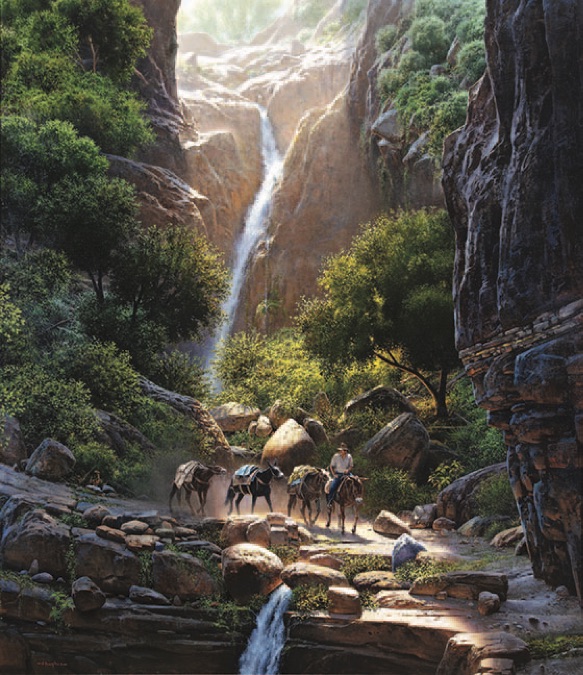

Bill Hughes, Canyon Passage, 1991

American, 1932 – 1992

Oil on canvas, 74 x 65 inches

When the Leanin’ Tree Corporation in Longmont, Colorado, announced it was closing its art museum and would be selling the contents, the Booth became quite interested in several works. Through discussions with the wonderful Trumble family, we were able to acquire three pieces for our collection, allowing them to continue to be available for the public. We added the sculpture Cosmos by Harry Jackson, the painting Oregon Pioneers by Gary Ernest Smith, and this work, Canyon Passage, by Bill Hughes, to our permanent collection. While these three were not the most valuable pieces in that collection, from an interpretative standpoint they are certainly three of the most important.

Hughes is a highly underappreciated landscape artist who often incorporated wildlife or cowboy elements. An Ohio native, he lived for a time in Los Angeles and Santa Fe, finally settling with his wife in an art colony near Scottsdale, Arizona. He was a proponent of a painting style he called actualism, a technique designed to draw the viewer into the scene so that they could imagine themselves moving through the landscape, which you can truly experience in this scene.

Visitors to the Leanin’ Tree Museum routinely listed this work as their favorite. In the relatively short time it has been in our collection, it has certainly stopped many visitors in their tracks. Hughes often said he preferred not to work from photographs, relying on his memory to conjure up scenes in his mind that might include slices of many locations stitched together to resemble reality. In this work it is his masterful handling of the light and the drama implied that most attracts visitors to stand before it and become immersed.

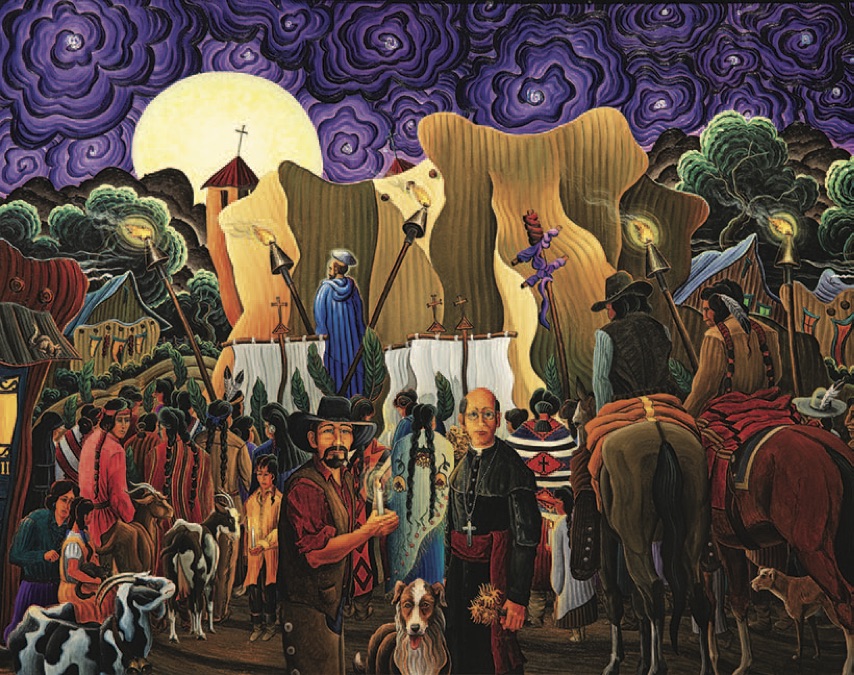

Kim Douglas Wiggins, Eve of St. Francis, Ranchos de Taos, 2003

American, born 1959

Oil on canvas, 60 x 76 inches

Another of the collecting goals of the Booth Western Art Museum is to collect not only the best of the living realist artists, but also those employing more contemporary styles over the same time period. This work by Kim Wiggins was created in a contemporary style, yet conveys many layers of history. It speaks to the multiculturalism evident in the Southwest, especially in Wiggins’ native New Mexico (he was born in Roswell) in the areas around Santa Fe and Taos. Wiggins has inserted himself into the composition as the cowboy in the foreground on the left; to his right is the famed Taos Society of Artists founding member, painter Ernest Blumenschein (shown as the priest), who has ceremonially passed the candle of inspiration from his generation of artists to the next.

The scene filling the background is the Eve of Saint Francis feast when American Indians were urged to bring their animals to the Catholic mission such as the one seen in the painting, in Ranchos de Taos, perhaps the most painted church in America. Wiggins explains that this is one of the areas where the Native people quickly latched onto the teachings of the missionaries — who would not want to bring their animals to be blessed, with prayers offered for their safety and productivity?

One of the leading painters in contemporary Western art, Wiggins is known for modern and fresh-looking expressionistic landscapes. Yet, as in this work, his contemporary vision has deep historical roots in the American West and works created a hundred years ago by artists such as Thomas Hart Benton, Maynard Dixon, and several artists associated with the Taos Society of Artists.

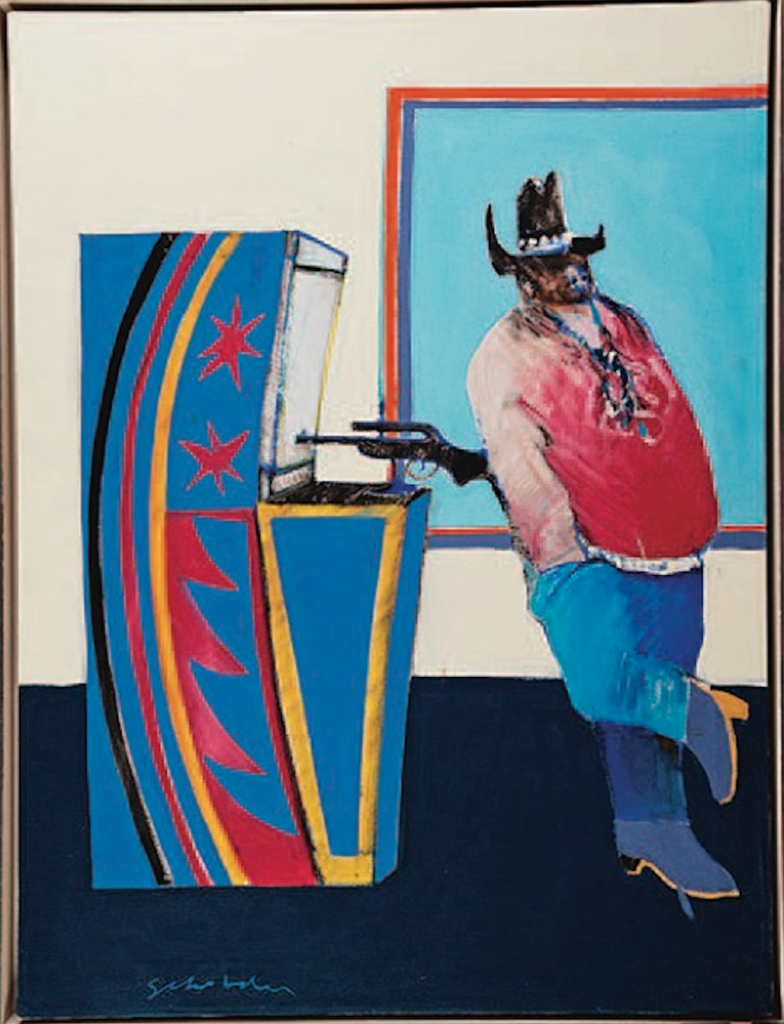

Fritz Scholder, Indian at a Gallup Bus Depot, 1969

American, Native American (Luiseño), 1937 – 2005

Oil on canvas, 40 x 30 inches

Fritz Scholder is arguably the most important Native American painter in our history, although he often rejected that description, being only about one-quarter Indigenous. A giant among contemporary artists, he was born in Minnesota and became one of the earliest instructors at the Institute of American Indian Art in Santa Fe in the 1960s, teaching some of the most talented early students to ever come out of that renowned school. Scholder sought to convey the contemporary Native American experience as a somewhat tortured one by including figures with contorted facial features dressed in modern clothing, juxtaposed with modern intrusions such as the arcade game seen in this work.

Created in the same vein as other early works — particularly Indian With a Beer Can, Super Indian No. 2, and Indians With Umbrellas — this painting juxtaposes a Native American wearing a mix of traditional Native and so-called cowboy clothes trying to live with a foot in both worlds: traditional Indigenous and the white man’s world. In my opinion this painting is one of the most important acquisitions the museum has made in recent years. If requests to borrow a painting are an indication of importance, this one certainly wins the prize, as it has traveled the most of any of the works in our collection.

Donna Howell-Sickles, Not Without Its Ups and Downs, 2001

American, born 1949

Mixed media, pastel, and charcoal on paper, 60 x 40 inches

Another leading artist in contemporary Western art is Donna Howell-Sickles. Raised on a 900-acre farm in North Texas and transplanted to New Mexico from junior high through high school, she returned to the Lone Star State for college. It was in the final year of working on her BFA at Texas Tech that Sickles got an old postcard from a fellow art student showing a cowgirl circa 1935 seated on a horse; the caption read “Greetings from a Real Cowgirl from the Ole Southwest.”

Although Sickles had grown up on a farm and ranching operation, she hadn’t considered herself Western, but this image spoke to her. Inspired by what she had thought was fictional imagery, Sickles later found out her inspirations were real rodeo contestants and performers, and they became iconic in her work. She has since created a body of work depicting women who are independent, strong, hopeful, and loving life — which is also how Sickles describes herself. Her works make you smile, but the more you ponder their metaphorical elements, the more you’ll likely determine there’s more going on than meets the eye. I once joked with the artist about this particular work that the cowgirl — straddling an enormous bull with sharp horns — looked awfully happy for somebody about to be thrown to her death. “She’s not being thrown to her death,” Sickles said. “She’s merely dealing with the ups and downs of daily life.”

A wonderful message to take away from our tour highlighting just 12 of the nearly 600 story-filled works on view at the Booth.

Images: Courtesy Booth Western Art Museum, Louis Tonsmeire Studio, John Mariana Photography

From our August/September 2020 issue.