The award-winning Choctaw-American singer-songwriter is out with deeply personal new music — thoughtful, cathartic, and terrific as usual.

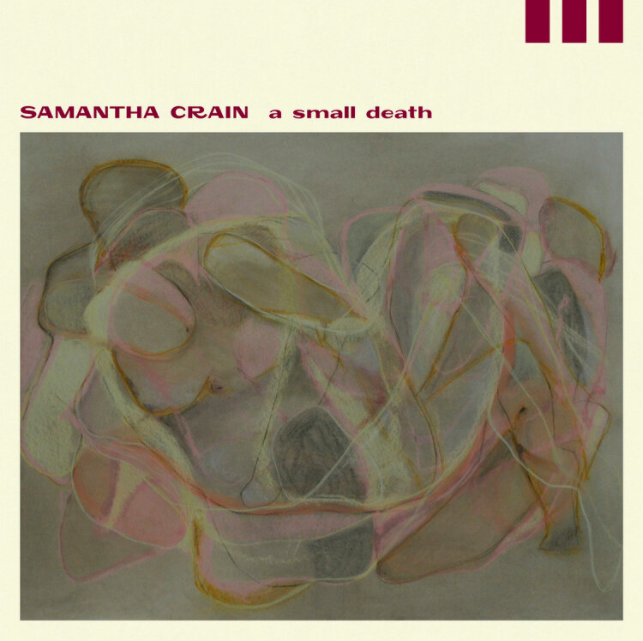

It’s like Christmas morning when Samantha Crain comes out with new music. And we’re thrilled to be opening a big gift in the full heat of summer on July 17, when the Choctaw-American musician releases A Small Death, her sixth studio album.

You can watch the video for the track “Pastime” from the album here. Directed by Crain herself, it hinges on spontaneity, “often forgotten as a great tool and teller of stories.”

Crain would know: She’s a great teller of stories. A two-time winner of the Native American Music Award, she makes profounly personal and poetic music that rocks even as it defies genre categorization — her 2019 Indigenous Music Award was, in fact, for Best Rock Album. She’s toured with a wide-ranging roster of artists, including the Avett Brothers, Neutral Milk Hotel, Brandi Carlile, the Mountain Goats, Josh Ritter, First Aid Kit, and Deer Tick.

The new record finds Crain confronting decades of grief, trauma, and physical pain that left her bedridden and barely able to perform or play an instrument.

“I didn’t completely die, but I feel like I died a little bit and that allowed me this new beginning,” Crain says. “What I was trying to capture with this record, really, was a sense of reconstruction.”

We caught up with Crain as she was locked-down in her native Oklahoma: “I’m just in Norman at home with my dog, Marty. I’ve been watching a lot of Turner Classic Movie Channel, going on walks, writing music, gardening.”

We dug in on her new music, her new video, and her new lease on life.

Cowboys & Indians: What’s the story behind the new record? How did it come together?

Samantha Crain: All of the songs on the record revolve around this two- to three-year period of my life where I was having an emotional and physical breakdown, hitting a rock bottom (so to speak), working my way through it, and coming out on the other side as a person legitimately giddy that they had been given a new lease on life — my bonus round is what I jokingly call it.

Around the time my last record came out in 2017, I started experiencing alternating intense pain and numbness in my arms, wrists, and hands due to tendonitis and carpal tunnel. At the time, I wasn’t in a good place mentally either. My abuse of alcohol was in a dangerous place and my brain was in all sorts of stress due to years and years of unaddressed trauma within my family and from my past. Around this time, I was also in three car wrecks all within the period of a couple months and having extreme body pains from that (that I was also self-medicating with alcohol).

The culmination of all this — it was as if every bad thing that had ever happened in my life was on a flat sheet and at this particular time something decided to gather up the corners and tie it all together and expect me to carry that around — led to me beginning to have panic attacks and created a temporary psychosomatic near-paralysis of my wrists and hands, which was exacerbated with my existing tendonitis and carpal tunnel.

When this started happening, when I couldn’t use my hands for hours during the day, it was the lowest point for me. And after the cancellation of my U.S. album-release tour, I began this long journey of various therapies, mental and physical, to deal with and discard everything that was causing these ailments.

It was a slow process of regaining emotional, mental, and physical health, but once I regained pain-free movement in my wrists and hands, I was incredibly grateful for the chance to play music again. And so I began the process of piecing together my thoughts and writings from my dark and depressing sick bed and the new outlook that I possessed and put these songs together. Because of the incredibly personal and devastating nature of the songs, I felt strongly about this being a record I produced myself.

C&I: Who’s playing on it? What were the recording sessions like?

Crain: I recorded it at Lunar Manor Studios in Oklahoma City, which is run by my friend Brine Webb, who I’ve known for 12 years. I needed to work with someone who could understand where I’ve been and what my journey had been and who I could trust to follow me down whatever path I wanted to take this record. So just the two of us worked on this record for about 80 percent of the time, and then periodically, we’d bring in some other musicians to flesh out the ideas.

We did a lot of the instruments and tape looping and then Paddy Ryan (John Moreland, Unwed Sailor, Parker Millsap, the Secret Sisters) came and played drums. I knew I needed him to play drums. He’s so solid and creative and tasteful. John Calvin Abney came in and played piano. He’s one of my dearest friends and I trust him completely. I’ve worked with him for a long time and his piano playing is always exactly the right mixture of weird modern classical meets Southern Baptist hymn. David Leach came in and played some upright bass. Kyle Reid played pedal steel and did some additional sound effects and sampling. Trevor Galvin came in and played saxophone and clarinet. Garrison Brown played some trumpet. Joanna Grace Babb (Annie Oakley, Spinster) sang some background vocals.

C&I: Tell us a little about the song “Pastime” and the performance-art-style video for it. What would you like listeners to get from it?

Crain: First, about the song: As I was in a time of reconstruction following this disintegration, I began to search for and learn about who I was as a person outside of my self-appointment and identification as the musician Samantha Crain. Without the physical ability to play instruments at the time, I spent time talk-writing poetry into a voice recorder, reading, walking, talking to people, living a quiet life. I felt like I was getting to know myself from scratch, peeling off a costume that I was put in as a child and allowing myself, for the first time, to dress myself and fully lean in to my curiosities and sensitivities.

This song phrases that journey as the excitement of the giddy and audacious stages of a new romance because I truly felt (and still do) in that way about finding these new facets of myself. The recording of the song, to find the tempo, I just paced the studio for a while to find the natural speed that I would find if I was on a long walk. I wanted the song to be trancelike, where you couldn’t tell if you’d been listening to it for 30 seconds or 30 minutes — that’s why those “ohm” voices are in the background ... meditative almost.

C&I: And the video?

Crain: For the video, my friend Blake Studdard shot and edited it and I directed it. It is meant to be a celebration of the community of the town I live in, Norman, Oklahoma, as well as a nod to the capture of improvisation. Spontaneity is often forgotten as a great tool and teller of stories and I wanted to have a day of filming the wonderful people in my community remembering and exercising the flustering and freeing practice of just winging it. One at a time, we would have people come onto our set, alone, having not heard the song, and not having much of an idea of what I’d be asking of them. We had a few props lying around and we’d play the song and I’d just say “Do whatever you feel — respond to the song, respond to me, respond to yourself; just wing it for the duration of the song.” And this video captures those moments.

C&I: You’re Choctaw, living in Norman, Oklahoma. What keeps you in Norman?

Crain: I’m not from Norman, I’ve just lived there for the past five years. I’m originally from Shawnee, Oklahoma. I moved around a lot in my 20s, living in different cities but eventually moved back to Oklahoma because I was getting priced out of every other city.

Oklahoma is a great place if you're a full-time artist. You can spend more time creating and less time slogging it bartending 60 hours a week just to pay rent. I also just think Oklahoma is weird and I like living in weird places. I think I misunderstood this place when I was younger. I felt like such an outcast. I couldn’t find anyone who liked the same music or clothes or movies as me. I couldn’t wait to leave.

But as I get older, I realize most people here feel like outcasts, like outsiders, always feeling like they have something to prove, and the real rewarding work is being vulnerable enough to form bonds and relationships with each other, not necessarily out of shared interests, but to learn something new, to learn to love in spite of the strangeness of each other.

C&I: Please introduce us to Choctaw culture. What would you like people to know and understand?

Crain: I am a member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. My ancestors were forced to relocate here during the Trail of Tears. The U.S. government wanted to acquire the Choctaw Nation’s land in present-day Mississippi so they could sell it back cheaply to plantation owners and farmers to prop up the continuation of the “too big to fail” business of slave labor. We are a peaceful people (historically and currently using the intense game of stickball — which is the precursor to lacrosse — to settle disputes rather than war or fight). We are an empathetic and giving people (sending money to Irish potato farmers during the great famine in the 19th century after hearing of their struggles). We are a resilient people (having the terms of every treaty we’ve ever signed with the U.S. government broken, we’ve still remained a thriving and active tribal community).

C&I: The Choctaw Nation website describes the people as “a tribe of artists, professionals, musicians, storytellers, innovators, leaders, athletes, warriors, and caregivers.” It’s interesting how much of that applies to you and how revered artistry is in that list. How does your music come to you? How do you compose?

Crain: Most of my songs start out as a small idea, either a song title or an event in my life or a little couplet of poetry I write down real quick or a brief melodic idea. I’m sort of a magpie in that way — I just keep tons of notes all the time, gathering information about my life and every stupid little idea I have and the world around me. I do this because otherwise I’d forget all the good stuff, or I’ll brush it off like it won’t be a good idea or it’s not complete enough.

So then, when I sit down to write, I like to have heaps of information and inspiration around me and just see what grabs me that day. And then I just get to indulge myself in an idea and take it as far as I can. Sometimes it turns in to a song, sometimes it just expands the idea a little, sometimes nothing happens.

I have so many stories to tell. Some days I’m just not ready to tell certain stories, but they are always there for when I’m ready to explore them. Some ideas take years from the conception to understand and expand on. I just like to have a consistently breathing organism of ideas collected around me and then, depending on the day or my mood or the time, I can reach in and conjure a song.

I try to keep as much information through documentation as possible, though, to make sure I can remember and think about my stories in the purest and most complete sense. I have hours of voice recordings of me just doing talking diary-type entries about things that have happened to me. Hours of melody ideas and car-steering-wheel drum rhythms. Books and books of little clippings of paper with poetry and words on it. Pages of phone memos. Hours of phone voice recordings.

You know those scenes in crime dramas where the person trying to solve the mystery has a wall of crazy pictures and string and scribbling? That’s how I feel when I’m writing — that's how my brain and my kitchen table look during the process. I work this way because I think better and see situations clearer when I’m removed from them by time and space. I want to document all the drama and emotion and passion as it’s happening, but I can’t really make the song about it until I’ve had time to process it and think about it.

I think I write about 75 percent my experiences and then 25 percent about stories of other people. In that way, although I love and appreciate the folk tradition, I am very much a product of the world of confessional songwriting. It is where I find my peace and it is my way of making sense of my journey through life.

After I feel like a song is finished, I’ll usually make a little demo recording of it at home and listen to it in the car or in my headphones for a few weeks, which gives me another perspective of its construction. Then I’ll try to play it live at a small show to get a feel for how it sounds and expands in a room and how people receive it. Sometimes I edit them, sometimes the songs die during this process, and sometimes they live and thrive to be recorded on a record.

For more on Samantha Crain, visit her website, or follow her on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, or Spotify.

Samantha Crain’s Feel Good Playlist

“Juma Mountain” — Sam Amidon

“Emotions” — Mariah Carey

“Chattahoochee” — Alan Jackson

“Collard Greens” — Schoolboy Q and Kendrick Lamar

“I Want to See the Bright Lights Tonight” — Richard and Linda Thompson

“Earth Angel” — The Penguins

“You Turn Me On, I’m a Radio” — Joni Mitchell

“That's Us/Wild Combination” — Arthur Russell

“Sex and Candy” — Marcy Playground

“Gotta Get Up” — Harry Nilsson

“Hammond Song” — The Roches

“Sugah Daddy” — D’Angelo

Photography: Image courtesy Joanna Grace Babb