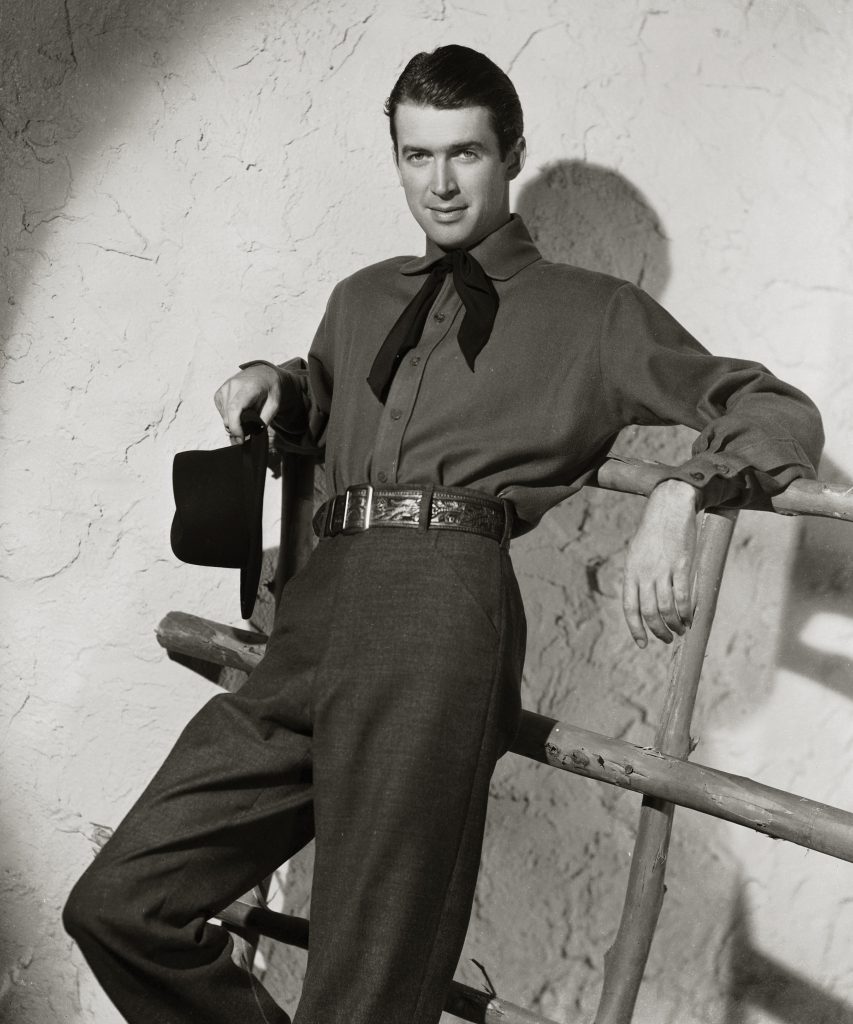

One of the most honored and beloved stars in film history, screen legend Jimmy Stewart returned from World War II a changed man who would change westerns.

To many of us of a certain age, James Stewart looked his most natural under his battered “lucky” Stetson, astride his chestnut gelding, Pie. Although not originally a western star, the 6-foot-3 lanky, laconic actor became one of the Cowboy Tetrad — alongside Henry Fonda, Gary Cooper, and the Duke — whom we grew up watching at the Saturday matinees and still watch in reruns whenever possible.

Even excluding his westerns, the list of Stewart’s essential films (two of them holiday staples) is impressive. In fact, the American Film Institute has placed five of his films — Vertigo, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, It’s a Wonderful Life, Rear Window, and The Philadelphia Story — on its America’s 100 Greatest Movies list. Add the movies in which he rode a horse and wore the hat and that legacy takes on even more character and appeal.

Although he often seemed born to the saddle and preternaturally “cowboy” in manner and speech, Jimmy Stewart was an Easterner by birth and upbringing. James Maitland Stewart was born of Scottish ancestry in Indiana, Pennsylvania, on May 20, 1908. His devout Presbyterian father owned a local hardware store and hoped Stewart would one day take over the family business; his mother was a pianist and music lover. Volumes have been written about his early years — Princeton education (a family tradition), involvement with various theater companies, early stardom, and man-about-town Hollywood reputation.

But it was his wartime service as a B-24 commander and combat pilot that informed his later, more mature roles. The lovable “aw shucks” drawling Stewart who portrayed 1939’s Tom Destry Jr. would be overshadowed by the more complex star of the darker “adult” westerns of post-World War II America. Although both periods gave us the “real” Jimmy Stewart and had much to recommend them, the grittier post-war oaters reflected the pain and trauma of his wartime experience.

A Star at War

Jimmy Stewart was inducted into the service in late March 1941 — nearly nine months prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor — and soon applied for acceptance in the U.S. Army Air Corps. An avid pilot, he had logged more than 400 flight hours in his own plane and felt that he could best serve what would soon prove to be America’s war effort by flying bombers.

Stewart showed an aptitude for flying military aircraft. However, although he was commissioned a second lieutenant in early 1942, given advanced training at various military airfields, and made a flight instructor on B-17 Flying Fortresses, neither the U.S. government nor MGM, Stewart’s powerful movie studio, was willing to see America’s favorite movie star shot down over Europe. He was kept stateside well into 1943, touring for war bonds and narrating training and recruiting films until the frustrated Stewart managed with the help of his agent to wangle a posting abroad.

Finally, on November 11, now-Capt. James Stewart — commander of the 703rd Squadron, 445th Bomb Group — helmed two dozen B-24H Liberators to England. From that point on, there would be no publicity tours. Jimmy Stewart would play an active part in the fight to liberate Europe.

The missions to which Stewart was assigned entailed flying in brain-numbing cold over enemy targets — including Berlin, Brunswick, Bremen, Frankfurt, and Schweinfurt — in the face of heavy flak and squadrons of German Luftwaffe fighters, and often without escort planes. There was no script, no director to holler “Cut!” Every time he went up, he was putting his and his men’s lives on the line.

On one occasion, Stewart’s B-24 took a direct hit just behind the nose wheel but managed to stay together throughout the flight. Immediately upon landing, the plane literally broke in two at the wing. As Stewart watched his bomber fall apart, he laconically commented, “[S]omebody sure could get hurt in one of those damned things.”

Stewart proved an able commander, well-loved and respected by his men. During his period of service, he was promoted to colonel and chief of staff of the 2nd Air Division and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross with two Oak Leaf Clusters, the Air Medal with three Oak Leaf Clusters, seven battle stars, and — from the French — the Croix de Guerre with Palm. He was one of only five servicemen to have risen from private’s rank to that of colonel in less than five years.

Coming Home

The Jimmy Stewart who returned home in September 1945 was a changed man. Forever gone was the boyish matinee idol who had caroused his way through late-1930s Hollywood. Physically, he had aged noticeably. His hair was graying, his hearing was permanently impaired — quite possibly from the constant roar of the B-24 engines — and his face reflected a hard-earned gravitas.

But the greatest change was to his psyche. In addition to overseeing bombing missions as operations officer, Stewart had personally commanded 20 forays through the flak-filled skies over France and Germany, regularly courting the ever-present possibility of death in the air. During the course of these missions, he had lost planes and men, and it had fallen to him as commander to write the letters home, informing families of the deaths of their sons and husbands, many of whom he had come to know well. For the rest of his life, Stewart refused to discuss his wartime experience.

On his return to Hollywood, Stewart worked to reestablish his film career. According to biographer Marc Eliot, “Stewart’s combat experiences left him emotionally scarred, and his deepening darkness perfectly positioned him for the ’50s, in which he made his greatest films.”

It was not happenstance that his first post-war film, It’s a Wonderful Life, starred Stewart as the deeply troubled, suicidal George Bailey. Although the film did poorly upon its 1946 release, it showed viewers a Jimmy Stewart they had never seen before. As his lifelong friend Henry Fonda said, “If you want to see the real Jimmy Stewart, you can find him in It’s a Wonderful Life.”

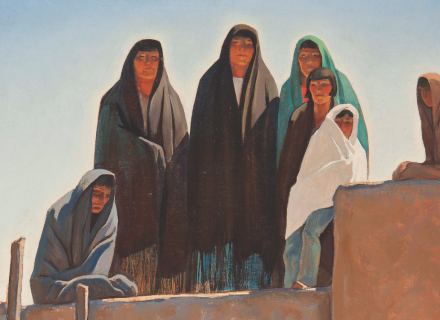

It would be another four years before Stewart would return to the western genre, starring in both Broken Arrow and Winchester ’73. The latter was the first of five dark, memorable westerns that marked Stewart’s collaboration with director Anthony Mann. It was a revenge tale that saw Stewart’s character nearly as ruthless as the man he pursued.

His performance in Winchester ’73 drew a surprising range of responses. While The New York Times review stated that he “drawls and fumbles comically,” Variety praised his “lean, concentrated” portrayal, and the New York Herald-Tribune’s critic commented that Stewart took to the role of a Westerner “as if he had been doing nothing else throughout his illustrious career.” For his part, Mann was thrilled with Stewart’s intense portrayal and would draw upon it for their next four westerns. According to Stewart biographer Michael Munn, “The Jimmy Stewart/Anthony Mann Westerns had really changed the genre for ever.”

Sadly, Stewart and the director largely responsible for reviving his career would eventually part on harsh terms, over Stewart’s insistence on producing the eminently forgettable western Night Passage. According to various sources, in addition to other production issues, Stewart saw the film as an opportunity to sing and play his accordion on screen, while Mann viewed the script as a potential disaster, reportedly proclaiming, “I will not make this trash.” Mann walked away from the film, and the two never spoke again.

Ultimately, the director was right. Wrote biographer Munn, “Night Passage ... was arguably Stewart’s worst western.”

Stewart’s later western career was not without other glitches. He was badly miscast as a wisecracking Wyatt Earp in John Ford’s Cheyenne Autumn — dubbed by one critic Cheyenne Awful. In two films, he was given unlikely screen “brothers”: Dean Martin in Bandolero! and Audie Murphy in Night Passage. In Firecreek, his dead-end loser of a character somehow manages to kill three of Henry Fonda’s gun-savvy outlaw gang with a borrowed pistol, emerging wounded but intact. And in Andrew V. McLaglen’s The Rare Breed, his performance is nearly drowned out by a bewigged Brian Keith’s scenery-chewing.

But in his classic westerns, Stewart’s character always rose to the challenge. With integrity and a quiet courage, he embodied the finest qualities of our ideal western heroes.

For more on Jimmy Stewart’s movie career

Movie Queue: Jimmy Stewart Westerns to Watch

Photography: Courtesy Universal Pictures/Photofest, MPTV Images

From our April 2020 issue.