Ken Burns returns to PBS with the definitive chronicle of rural America’s music.

Country music was born in Dallas. No, not the country music you hear on every other radio station in the parts of America where church picnics outnumber trendy brunch spots. Country Music, as in the new eight-part Ken Burns PBS documentary that should have you glued to your TV starting September 15.

The seed of the project was planted about 10 years ago when the prolific filmmaker — Burns has made more than 30 documentaries, has six films currently in production, and is booked through 2030 — was having dinner with friend Cappy McGarr at Suze restaurant in Dallas. The well-known private equity investor, political fundraiser, and special advisor to the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts told Burns his next film should tell the story of the music of America.

“He said, ‘What are you talking about? I’ve already done Jazz,’ ” McGarr recalls. “I said, ‘Ken, you have not done country music, and that is the music of America.’ ”

After dinner, Burns called longtime writing and producing partner Dayton Duncan to ask what he thought of the suggestion.

“It took me less than a minute to say it’s a terrific idea, but only if I get to write and produce it,” Duncan says.

Thus began the latest effort in a collaborative history between Burns and Duncan that dates to the trailblazing 1990 series The Civil War, still the highest-rated documentary series ever aired on PBS, having reached 38.9 million viewers during its initial five-episode run in September 1990.

By now, the reliable rhythms of Burns’ documentaries have become as familiar a part of the American landscape as the clanging of midnight trains and lonesome cries of whip-poor-wills. Burns fans will feel instantly at home with the style and pace of Country Music, which emerges as the definitive history of the quintessential American art form and another masterpiece among the many masterpieces he’s created.

More than 500 songs are featured. Expert commentators include Marty Stuart, Dwight Yoakam, and Willie Nelson. With his pitch-perfect Dust Bowl-grit-meets-L.A.-savvy delivery, actor Peter Coyote is perhaps more suited to this material than any of the more than 120 films (Burns’ and others) he’s narrated. McGarr, for one, believes Country Music will end up as one of Burns’ most popular works.

The series picks up in 1923 with legendary recording engineer and producer Ralph Peer recording Fiddlin’ John Carson in Atlanta. That session produced what would become arguably the first commercially successful recording of country music, an 1800s minstrel song called “The Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane.”

From there Burns tracks the story of an ever-deepening expression of the rural American journey with a roll call of titans from Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family to Earl Scruggs and Patsy Cline to Chet Atkins and Reba McEntire. With what has become a Burns trademark, the stories and songs of each artist are cannily woven into the context of the times, be it hitmaker Charley Pride breaking country music’s color barrier (Burns likens him to baseball’s Jackie Robinson) or Loretta Lynn writing and singing proto-feminist songs long before most artists dared approach the subject.

“We pretend that country music is about pickup trucks and hound dogs and six-packs of beer when in fact it is speaking directly about the joy of birth and the sadness at death, about falling in love, being so lonesome you could cry and seeking redemption,” Burns says. “This is a music that deals with two four-letter words we spend a good deal of our waking hours avoiding talking about, and that’s pain and love.”

Hillbillies, Cowboys, Outlaws

Even for dedicated fans of the genre, Country Music is filled with revelations. Some caught even Burns off guard.

“I don’t know a film I’ve worked on aside from Not for Ourselves Alone [The Story of Elizabeth Cady Stanton & Susan B. Anthony] that’s more about strong women than this one,” Burns says. “That was a huge surprise. In Loretta Lynn’s extraordinary gift as a songwriter. Or Dolly Parton and her gift at absolutely everything.”

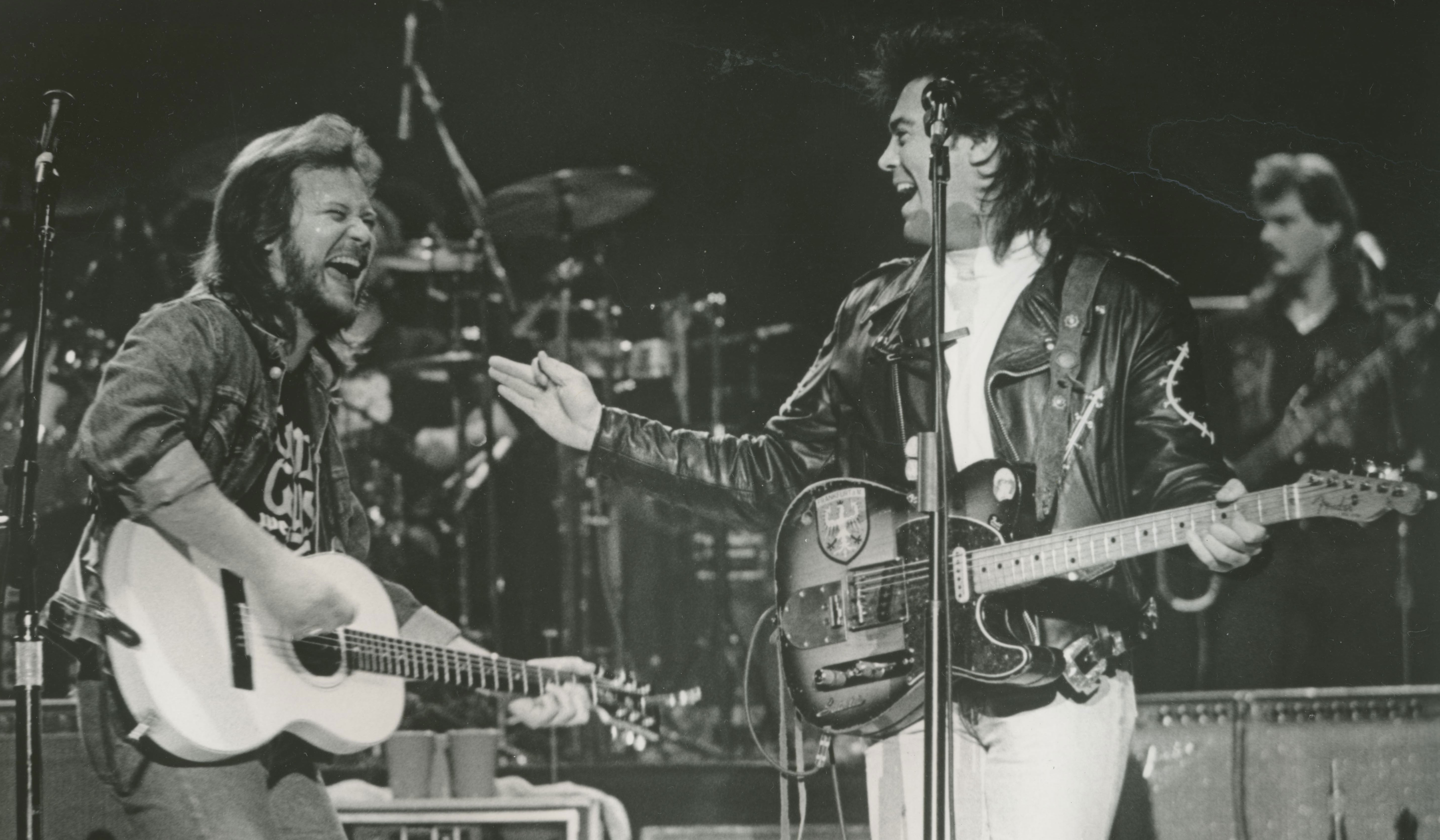

Casual country fans may be surprised to find the lens lingering on Emmylou Harris, but she’s another figure Burns approaches with touchstone reverence. “She’s central to the resurrection of country music’s roots,” he says. “She stands astride a huge intersection of rock and folk and country music in the 1970s that helped mitigate the smoother sound of Nashville, or Countrypolitan.”

Merle Haggard is the country colossus perhaps most venerated by a revolving cast of musicians and experts who provide context and color. “Merle Haggard all by himself saved country music,” says country star Ronnie Milsap, who came of age in the 1960s fixated on Motown.

A Burns film wouldn’t be a Burns film without some obscure personality turning into a breakout star by virtue of insight, wit, and candor. In the case of Country Music, Hazel Smith seems destined to be that character. The onetime girlfriend of Bill Monroe and later office manager at Nashville’s “Hillbilly Central” studio — where, among many other seminal recordings, Waylon Jennings’ 1975 Dreaming My Dreams was produced — tells the story of how she coined the term outlaw music to describe the style that ambushed Nashville and kick-started a musical revolution in the 1970s.

“We didn’t have any notion of just what a great force of nature and presence Hazel Smith would be,” Duncan says. “Every time she’s onscreen we know we’re in a good place.”

“We did 101 interviews and we used about 80 of the people we interviewed in the final film,” Burns says. “Unfortunately, about 20 of those people we interviewed have since passed away, including Hazel and Merle Haggard and Ralph Stanley. Fortunately, we at least have their interviews.”

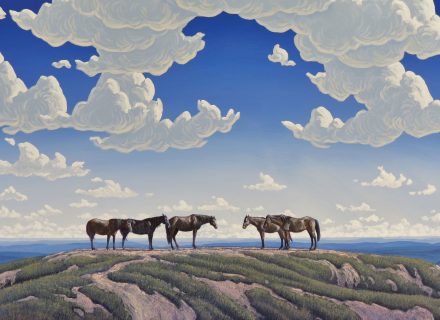

The country world’s outlaw antiheroes — Willie, Waylon, Merle — personify the westward migration of country music. It’s a theme that plays into one of Burns’ and Duncan’s primary areas of expertise. Burns, of course, produced 1996’s The West, a nine-part opus that chronicles the turbulent history of the most spectacular landscape on earth. The author of 13 books, Duncan wrote and produced 1997’s Lewis & Clark: The Journey of the Corps of Discovery, for which he won a Western Heritage Award from the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum and a Spur Award from the Western Writers of America. More recently, he wrote and produced Burns’ The National Parks: America’s Best Idea (2009), for which he won two Emmy Awards.

“In my more than 30 years of traveling throughout the West and trying to come to an understanding and explore the relationship between that magnificent land and who we are as people, country music was my soundtrack,” Duncan says. “Driving where I might be the only car on the road for three or four hours, you might hear anything from ‘Cool Water’ by Sons of the Pioneers to Chris LeDoux to Waylon Jennings and Emmylou Harris blasting out my window.”

Truth Tellers

In terms of temperament and style, Burns and Duncan aren’t quite Willie and Waylon, but they do make a formidable creative pair. Burns grew up in Delaware and Michigan. Duncan was born and raised in Iowa and has spent the last 40 years in New Hampshire. They met in 1979 and were friends before they became collaborators. The intense interest in American history and social movements that drew them together remains as central to their relationship today as it did when as a still largely unknown filmmaker Burns began working on his Civil War film with author Duncan.

“When we realized that on the Fourth of July we both read the Declaration of Independence aloud to our children, we knew we had something in common,” Duncan says.

Despite the congenial, folksy tone conveyed by his films, talking with Burns is like walking past a fireworks stand with a lit match. Suggest that despite its immense commercial popularity country music is still stigmatized by a sizable percentage of the American public and he’s quick to go off. Country is a unifying force, he insists, not a divisive one.

“We can waste time looking for the binary, but really what we’re looking for is an art that subsumes all that,” he says, sounding slightly defensive. “You can focus on that glass half-empty, but you can also look at it the way in which the glass is half-full. I’ve got a 16-and-a-half-hour series that can come to your rescue. I’m the cavalry coming over the hill.”

During the process of putting together a film, the push-pull that arises from collaboration inevitably surfaces. But Burns and Duncan believe giving up small pieces leads to a more satisfying whole. Even in a documentary spanning eight episodes, a lot of tough debates led to a lot of valuable material winding up on the editing-room floor.

“Each of us would probably say while the film you’re seeing is not necessarily in every respect the film that either one of us would have made on our own, it’s better than the one we would have made on our own,” Duncan says.

A theme that emerged during research that both filmmakers and co-producer Julie Dunfey quickly agreed on is the popular quote from songwriter Harlan Howard that defines country music as “three chords and the truth.” The line pops up in the first episode, and in each episode that follows, the concepts of truth and authenticity come back around like a good chorus.

“It is certainly a unifying theme around which the entire series revolves,” Burns says. “What does ‘three chords and the truth’ mean? It means while the music might lack the complexity and sophistication of classical music or some kinds of jazz, it is essentially mainlining basic human emotions, things all of us experience.”

Another of Country Music’s driving themes is that there is no such single thing as “country music.” The types of music now popularly categorized as “country” are in fact as varied as the music’s many geographic hotbeds — Appalachia, the Deep South, Texas and Oklahoma, Central California — and roots that range from Anglo-Celtic ballads to African American gospel and blues. From the beginning, purists have attempted to confine the definition of country while newcomers have fought to expand it.

“Country music has never been one thing,” Burns says. “It’s always been many things.”

A meteoric example is Bob Wills, who grew up in Texas in the 1910s and ’20s listening to African Americans playing blues, spent time in New Mexico with Spanish and Mexican musicians, and was powerfully influenced by the swing era. Wills added drums to what was then known as “hillbilly music,” then electrified a steel guitar to create Western swing. But Wills’ story wasn’t all wine and San Antonio roses. The bandleader suffered through five divorces in six years, was a binge drinker, and endured great bouts of depression. These are the types of emotional details that have gilded Burns’ golden reputation as a filmmaker. Country Music delivers a wagonload in each episode.

“Country” by Any Other Name

With its many faces and sounds, country music has always struggled with its self-identity — not to mention its labels.

Before World War II, thanks largely to Ralph Peer, the music was widely marketed as “hillbilly music.” Not everyone loved the phrase or saw the humor, but the revenue was inarguable. According to the 1936 article “The Inside Story of the Hillbilly Business” by Harry Steele for Radio Guide, cash registers at the time were “[ringing] ... to the tune of $25,000,000 a year.”

A variety of handles have flourished for brief periods over the years. Dayton Duncan explains that Billboard magazine’s first popularity charts lumped it all under “Folk Records.” Then came “Country and Western” (Ernest Tubb lobbied for that one). In 1958, a group of industry executives worried about the fading appeal of cowboy culture formed the Country Music Association and eventually persuaded Billboard to refer to the music simply as “Country.”

Six-Pack Perspective

If there’s one thing likely to disappoint some viewers, it’s the lack of current artists covered in the film. With the exception of a poignant coda dealing with the death of Johnny Cash in 2003, Country Music essentially concludes in 1996, with the ascendancy of Garth Brooks heralding the modern country era and the death of bluegrass icon Bill Monroe, who’s covered extensively throughout the series.

After following the long and dusty trail of country history, it may feel a little anticlimactic not to see the context in which the filmmakers might place superstars such as Blake Shelton and Carrie Underwood, guitar heroes such as Brad Paisley, songwriters such as Eric Church and Kacey Musgraves, and cult heroes such as Ray Wylie Hubbard and Robert Earl Keen. Burns prefers to sacrifice such tempting shots for mature sobriety.

“People are disappointed we don’t talk about their contemporary favorite stars,” he says. “We consciously put on the brakes 25 years out, not to offend people, but in order to not make judgments about people whose significance may not yet be appreciated. Perspective in history comes from the passage of time.”

“In the 1970s on country radio, you weren’t going to hear much Townes Van Zandt or Guy Clark, but they’re important figures,” Duncan adds.

The truth that breathes life into Country Music is constantly evolving. What historians will make of the last couple decades — when a lot of country music does in fact seem to be about pickups and six-packs — remains to be seen. What’s certain for now is that Burns and Duncan have produced an epic work based on the simple yet strangely complex notion that the country has more in common than it usually gives itself credit for.

Quintessential Country

Acompanion CD set from Sony Music will be released along with the PBS series Country Music. We asked director Ken Burns and writer-producer Dayton Duncan to kick off a playlist with some of their favorite songs.

“Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down,” Kris Kristofferson

“One of the greatest writers of 20th-century music,” Burns says. “I didn’t say country music. I said music.”

“Seven Year Ache,” Rosanne Cash

“I don’t think she would describe it as a classic country song, but it is a country song,” Duncan says.

“Mama’s Hungry Eyes,” Merle Haggard

“I was stunned at how central Merle Haggard is to country music, how extraordinary his stuff is,” Burns says.

“Jolene,” Dolly Parton

“The very supernova of her persona can sometimes make you forget how great of an artist she actually is,” Duncan says.

“I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” Hank Williams

“It’s about as simple as it gets and says it all,” Burns says.

From the October 2019 issue.