A group of Indigenous artists changes the conversation about Native American art and experience.

The artists who make up the Creative Indigenous Collective resist classification. So does their art, which ranges across cinematography, textile design, airbrush painting, and quillwork. But members of the collective share a single purpose: They create to lend voice to their people. To counter stereotypical and romanticized portrayals of Native culture, they present Native artists’ own unique perspectives of their history and of contemporary society.

The artists — Robert Martinez, John Isaiah Pepion, Holly Young, Lauren Monroe Jr., Louis Still Smoking, Gina Still Smoking, and Ben Pease — met through an art exhibition. Hailing from four Northern Plains states and six American Indian tribes, they come together through weekly conference calls to share ideas and advise each other on how to utilize different mediums for creative projects. In addition to producing the first contemporary Native American art exhibition at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, in 2018, Creative Indigenous Collective artists teach intensive workshops for high school students and also work with reservation schools and youth programs.

Click on the image above to view the slideshow of Robert Martinez’s art.

Robert Martinez

On the second story of his house outside of Riverton, Wyoming, Robert Martinez works in his airy studio. The walls pulse with his expressive portraits. This Northern Arapaho artist specializes in the airbrush technique. Air compressors squat next to desks cluttered with air guns and brilliant paints. “I use bright colors because people are so used to seeing Natives depicted in sepia or black-and-white photography,” Martinez says. “And, in seeing that, you think Natives are not around anymore — [that] they’re a dead people.”

Martinez first learned about airbrush painting at an amusement park. “I sat there — I was about 12 — watching those guys airbrush T-shirts and hats for over an hour,” Martinez recalls. His parents bought him an airbrush and a compressor, and he learned the air gun’s temperament and how to fix his mistakes. By age 16, he was airbrushing cars on commission. Three years later, he graduated with a bachelor of fine arts specializing in painting and drawing from Rocky Mountain College of Art and Design.

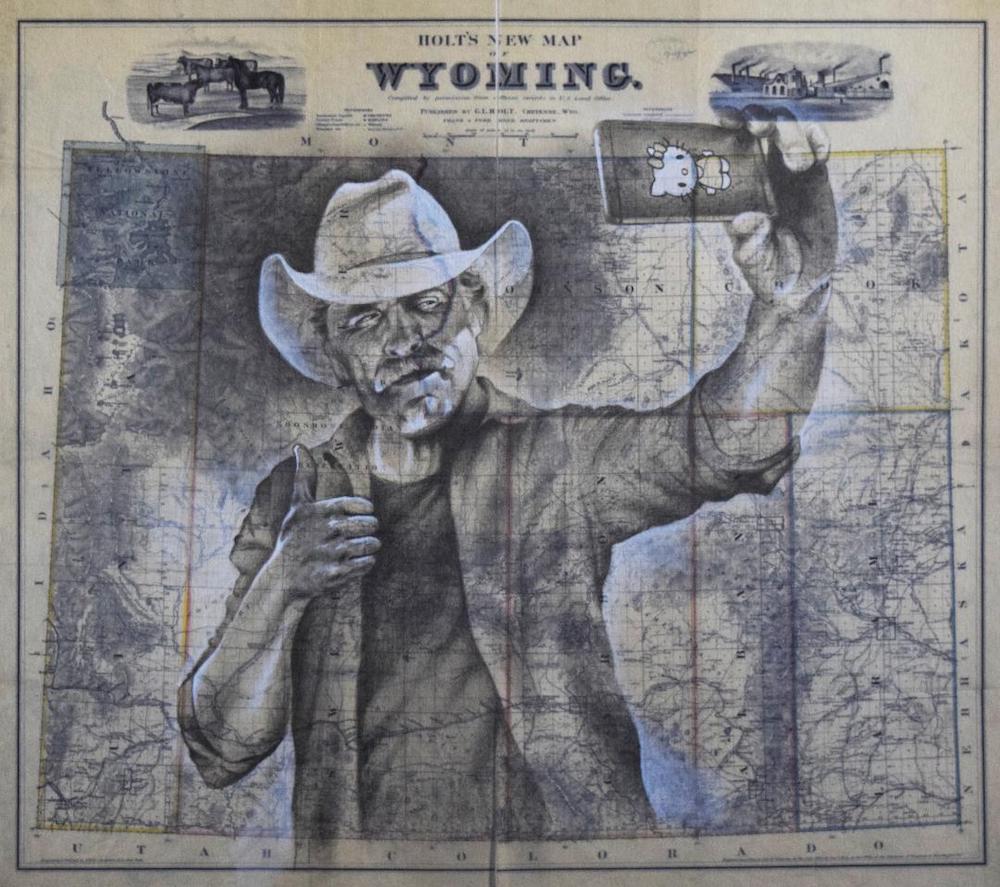

Renaissance masters, comic book artists, and fantasy illustrators influence Martinez’s style. Trained in classical painting, Martinez first sketches on images of vintage ledger paper or maps. If he likes the drawing, he then transfers the design, minus the ledger background, to canvas. Arapaho symbols pop out of his paintings as two-dimensional elements created from layers of canvas: morning and evening stars, buffalo hoof prints, and triangular configurations representing mountains or arrows.

A single portrait might include an 1800s headdress, 1990s-era boombox, and breakdancing. “I recently drew a ledger art with a cowboy taking a selfie,” Martinez says. “I titled it Hello Cowboy, because the cell phone case has Hello Kitty on it. I like to poke holes in the romantic ideas of Natives and the West.” martinezartdesign.com

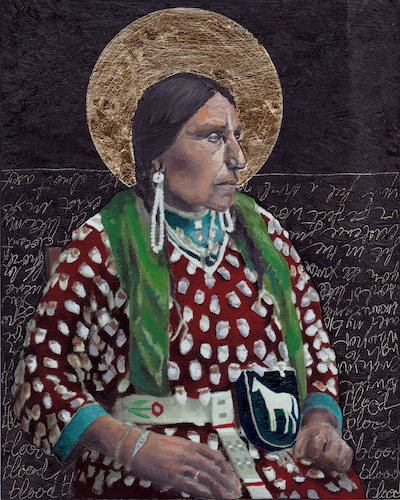

A Piece of Me by Lauren Monroe Jr., acrylic, 24 inches x 36 inches.

Lauren Monroe Jr.

As a boy, Lauren Monroe Jr. watched his grandfather, Gordon Monroe, create sculptures near Browning, Montana. But Monroe didn’t find his own artistic style until he studied English literature at the University of Montana in Missoula. “Art calmed my frustrations from my first time living off the reservation,” says the Blackfeet acrylic painter and aspiring filmmaker. “The quiet activity of painting lifts stress from me.”

Monroe continued his education to earn a master’s in screenwriting. But he circled back to art therapy and is currently working on his doctorate in curriculum and education at the University of Calgary. “My interests are eclectic,” he says. “But it’s all grounded in my Blackfeet culture and my contemporary reservation experience. My art is a form of therapy to understand myself and what happens in my life.”

Monroe has written two film scripts. He directed and produced one, Kills Last: A Blackfeet Coup Story, as a short sci-fi film in 2018. Filmed on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation, it features actors mainly speaking in the Blackfeet language. “For Kills Last, I looked toward the future,” Monroe says. “What’s our next stage? How do we reconvene with our land and language?”

Monroe serves as an instructor and program coordinator for the University of Calgary’s Blackfeet Cosmology and Culture master’s program for Blackfeet Confederacy reservations. “Art is so vital to developing positive lifestyles and creativity,” he says. “We’ve been through so much as a people. It’s crucial that we continue our visual arts, our practices, and have the history behind them. We are distinct. We’re not just a Plains culture. We’re Blackfeet people. We’re Piikani.” laurenmonroeart.com

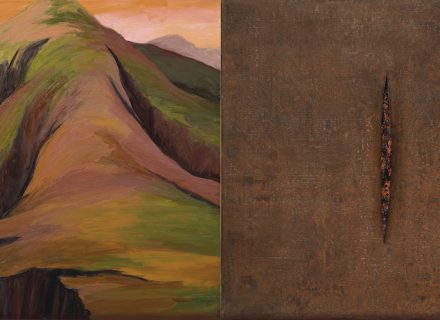

Future In Our Eyes by Ben Pease, acrylic on antique ledger paper on canvas, 48 inches x 36 inches.

Ben Pease

The world of Western art enthralled Crow/Northern Cheyenne artist Ben Pease when, as a youth, he visited the C.M. Russell Museum’s Out West Art Show in Great Falls, Montana, with his mother, Linda. “As a young teenager, I had rarely been off the [Crow Indian] reservation,” Pease recalls. “I saw all these different facets of my culture, but I could tell it wasn’t really my culture. It was a farce: ‘Paintings of Indians’ in their natural habitat, people dressed in buckskin pants and shirts, amazingly large turquoise jewelry, and big hats. I then realized non-Native people were employing falsified stereotypical representations of pan-Indianism solely for appearance and profit, which I’d never seen outside of my own culture. So I was in the midst of culture shock, within a culture trying to dress like my culture, create like my culture, and profit from my culture. I had many questions, and I still do.”

That year, Pease watched Crow artist Kevin Red Star in the quick-draw event. “In his art, I saw myself, my community, and an authentic voice in a sea of appropriation,” says Pease, who now resides near Billings, Montana. After high school, Pease headed to Minot State University on football and art scholarships. There he studied under contemporary Western artist Walter Piehl. Later, Pease transferred to Montana State University, where he learned from contemporary artist Rollin Beamish.

That year, Pease watched Crow artist Kevin Red Star in the quick-draw event. “In his art, I saw myself, my community, and an authentic voice in a sea of appropriation,” says Pease, who now resides near Billings, Montana. After high school, Pease headed to Minot State University on football and art scholarships. There he studied under contemporary Western artist Walter Piehl. Later, Pease transferred to Montana State University, where he learned from contemporary artist Rollin Beamish.

Pease artistically melds historical and contemporary digital drawings, oils, acrylics, spray paint, oil pastels, and antique paper ephemera. “I recently started a portrait of a Cheyenne woman,” Pease says. “In the middle of painting it, I decided to add a Basquiat-style crown upon a classical Byzantine-inspired halo. This imagery references the contrasting effects of the imposition of colonization and Christianity upon a people previously existing in their own evolved cultural philosophy, belief, pedagogy, and ontology. It also relates to my cultural belief that women are closest to the Creator of All Things.” In his creative process, he says, he lets a piece go where it wants to go for organic, inherently powerful creativity.

“We’re a people reverent of our past, present, and future,” Pease says. “We respect that our ancestors guide us. We must understand that our past is still alive with our current selves and our future. I want my art to represent that experience, as our timeless voice continues.” benpeasevisions.com

Click on the image above to view the slideshow of John Isaiah Pepion’s art.

John Isaiah Pepion

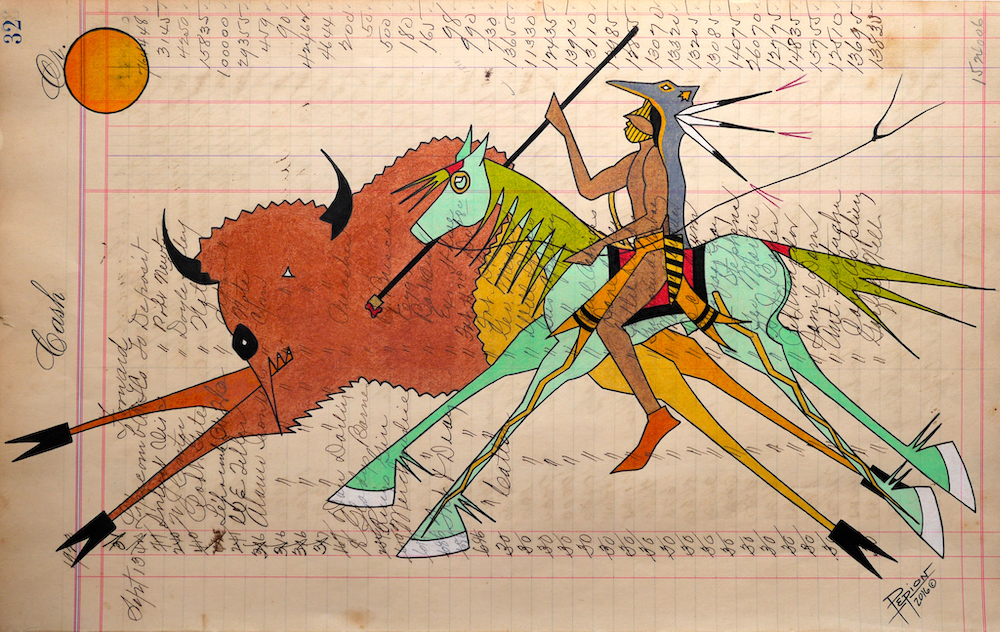

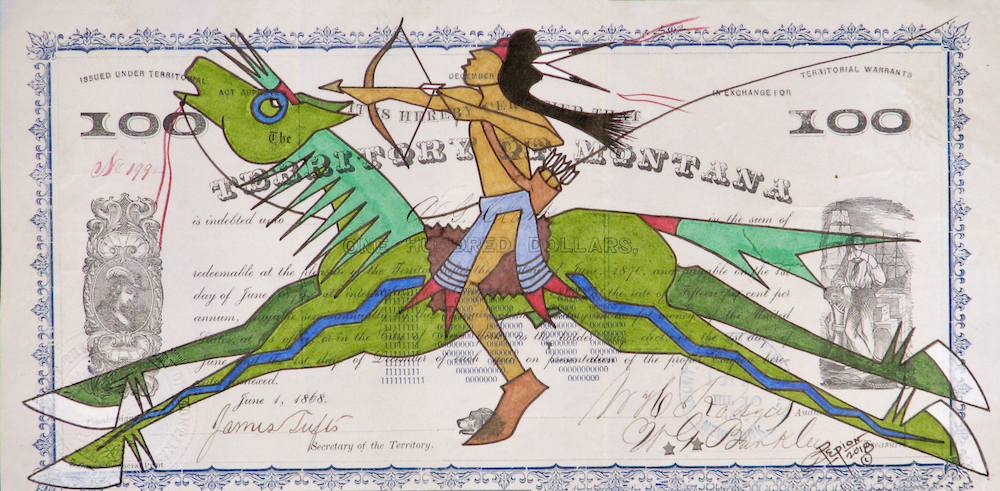

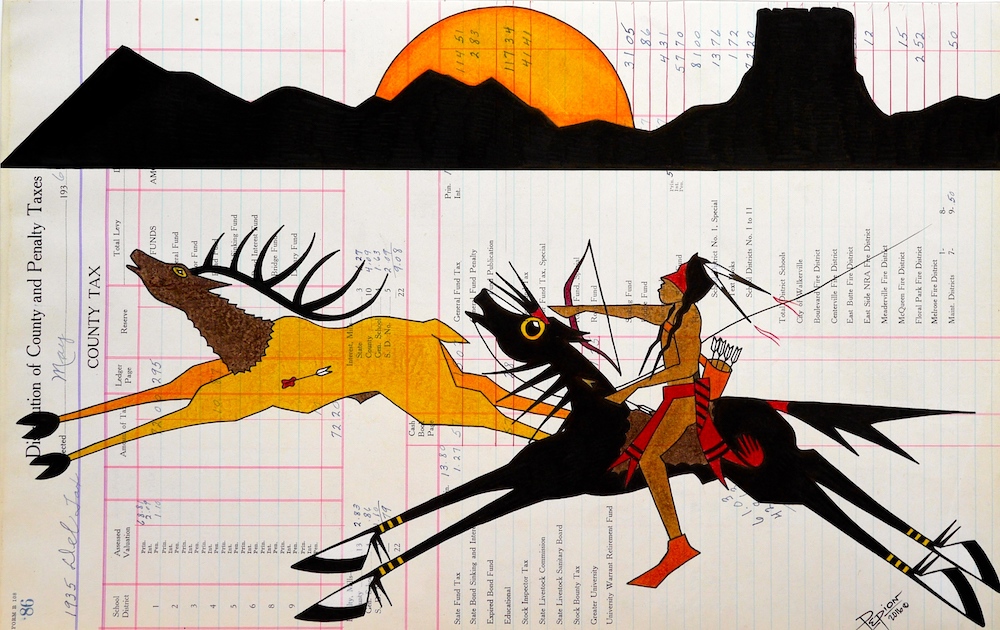

John Isaiah Pepion didn’t intend to be an artist. It’s not that he didn’t know about the career: Most members of his family are artists. Growing up on his grandfather’s ranch near Browning, Montana, Pepion wanted to be a museum curator. In fact, the Blackfeet artist holds degrees in art marketing and museum studies from United Tribes Technical College and the Institute of American Indian Arts, respectively. But a long period of physical therapy to recover from injuries sustained in a 2009 car wreck prompted him to pick up brush, pen, and pencil. “I haven’t stopped creating art since,” he says. “To me, it’s therapy. I just enjoy it.”

Working out of his studio space at his home in Birch Creek, Montana, with his mother, brother, and aunt as neighbors, Pepion employs his curatorial skills to accurately portray his Blackfeet tribe. He utilizes ink, paint, and colored pencils to apply his unique Plains Indian graphic artwork to ledger paper, rawhide, tepees, and buffalo skulls. The horse, which is frequently found galloping across his art, is Pepion’s favorite subject, and he has ready subjects in the horses that belong to his aunt that roam through his front yard. His pictographic style captures the horse exaggerated with extra-long legs and larger hooves. “It’s from how animals stretch and their legs lengthen when depicted on painted tepees,” Pepion says.

“Through art, I tell my story, just as the traditions of my family are told in the artwork they left behind,” he says. “My ancestors painted war records and important times of our tribe on buffalo hides and old tepee liners.”

Art, Pepion says, pushed him to learn who he is. “I want to correctly illustrate my ancestors, my culture, and my community.” johnisaiahpepion.com

Honoring the Day by Louis Still Smoking, oil, 16 inches x 20 inches.

Louis and Gina Still Smoking

The husband-and-wife artistic duo Louis and Gina Still Smoking of Pierre, South Dakota, infuse social awareness into their textile and clothing designs. Their fashion shows highlight not just their handprinted textiles, but also something akin to performance art that grapples with societal issues like missing Indigenous women, sexual abuse, and suicide awareness.

Their 2017 Western Art Week Fashion Show at the Paris Gibson Square Museum of Art in Great Falls, Montana, was inspired by a poem, “A Lakota Wildflower,” that came to Gina, a Lower Brule Sioux tribal member, during a sleepless night. She designed the show to tell the story of sexual abuse of Lakota women.

The runway show began by showing clothing modeled after youth and innocence. Then the clothing turned somber, presented by messy-haired models wearing tear-smeared mascara. The show progressed to a model that wore a mask to hide from the world. “Then it switched to our more colorful line to show that, ‘Now I’m growing — recovering — into a different person.’ I was so excited for the amateur models’ stage presence that I didn’t look around during the show,” Gina says. “Afterward, I found everybody was crying.”

Still Smoking Designs was born out of a Montana State University class project. For the class, Louis carved a woodblock to print a banner. Friends requested the design on T-shirts, and the couple expanded from there. For Gina, it’s a childhood dream realized. “Where I grew up in South Dakota, there weren’t avenues to learn fashion design, and it was not encouraged,” she says. “It’s almost like fashion design turned around and found me instead.”

Gina reports that they’re often asked if it’s culturally appropriate for non-Native people to wear Still Smoking Designs clothing. “Anyone can wear our designs,” Gina says. “We never use ceremonial elements, which we prefer to not be worn outside of sacred use.”

Traditionally, for both the Lakota and Blackfeet (Louis’ heritage), clothing design was based on dream interpretations. “That design was tied specifically to the person who created it,” explains Louis, who also sculpts and paints. “We are modern individuals, but we can still use that mentality to create our personal designs. We don’t copy somebody else’s design. We create our own from our interpretation of life.”

Louis, who two years ago pulled back from his involvement in Still Smoking Designs to dedicate more time to his own art, imbues his oil and mixed-media paintings with this philosophy. “I really try to contextualize my paintings so that the viewer can learn how diverse Native people are,” he says. “Currently, I focus on expressing how modern Natives fit into society. Each piece features Native and non-Native components, because that’s how we live. We’re Native, but we’re also human, just like you.” stillsmokingart-designs.com

Beaded pipe bag by Holly Young, 4.5 inches x 16 inches.

Holly Young

As of 2018, there are 573 American Indian tribes or nations in the United States. Each tribe or nation possesses its own unique culture, but over the centuries, tribes have also adopted traditions from other peoples. Dakota artist Holly Young discovered this firsthand in her research of quillwork artifacts. She found that originally, her Dakota people created floral designs — not the geometric motifs they fashion today. “In my community,” explains Young, who lives in Bismarck, North Dakota, “the floral designs and quillwork process were almost lost to history.”

A 2016 residency with the Minnesota Historical Society gave Young the opportunity to delve deeply into American Indian design history. “Dakota floral design entwines the plants and flowers of our prairie,” Young says. “I recognize them from when I was a kid running on the prairie at my grandparents’ place.”

Young revitalizes Dakota floral design for her people and future generations, creating it in her beadwork, quillwork, and ledger art. Young is most dedicated to quillwork. “I harvest quills from roadkill,” Young says. “Friends message me and give the location where they saw dead porcupines. I usually pluck the quills off on the side of the road.”

Young has fashioned earrings, vests, moccasins, baby amulets, wallets, coin purses, and tobacco bags. A pair of Young’s gauntlets won second place at the 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market. “Bead workers will bead anything and everything,” Young acknowledges with a laugh.

Because Young couldn’t locate people to teach her how to bead and quill, she practices Winyan Omniciye — the circle of sharing knowledge. What you learn, you give back. “I want to share the techniques I’ve learned and the designs from the [artifact] collections I’ve studied,” she says. “It serves no purpose, for my people or other communities, to hold this knowledge to myself.” instagram.com/holly_young_artist

Find the Creative Indigenous Collective artists’ work at the September 2019 Northern Plains Indian Art Market in Sioux Falls, South Dakota; the October 2019 North American Indian Art Market in Salt Lake City, Utah; the November 2019 Brinton Museum 101 Show in Sheridan, Wyoming; and the 2020 – 21 Counting Coup: An Apsáalooke Exhibition at the Chicago Field Museum. creativeindigenouscollective.com

Photography: (featured) Native America the Beautiful by Robert Martinez, airbrushed acrylic and oil on linen, 4 inches x 6 inches; (slideshow) Hello Cowboy by Robert Martinez, graphite and acrylic on vintage map image, 18 inches x 24 inches, Come and Get Your Love by Robert Martinez, graphite and acrylic on vintage map image, 18 inches x 24 inches, Native America the Beautiful by Robert Martinez, airbrushed acrylic and oil on linen, 4 inches x 6 inches, As the Crow Flies, by Robert Martinez, graphite and acrylic on vintage map image, 11 inches x 14 inches; (middle photo) Green Horse by John Isaiah Pepion; (inset) Sitting Bird by Ben Pease, oil on Arches cold press on panel, 8 inches x 10 inches; (slideshow 2) Buffalo Hunt by John Isaiah Pepion, Green Horse by John Isaiah Pepion, Elk Hunt by John Isaiah Pepion

From the August/September 2019 issue.