Chaz John gives a lot of canvas time to man’s best friend for his new show at Ellsworth Gallery in Santa Fe this August.

Last year, while still a student at the Institute of American Indians Arts in Santa Fe, Chaz John exhibited a series of paintings and drawings entitled Rez Dogs at Ellsworth Gallery. Celebrating the survival and resilience of dogs who live and roam on reservations, the show pulsed with the ironic energy of presenting seemingly low-brow subject matter in a high-brow environment.

Since then, John’s work has been increasingly influenced by Victorian dog portraiture and his painting style has expanded — all of which can be seen in his new show, Rez Dogs II, on view at Ellsworth Gallery August 9 through September 2.

“From the beginning of his 2018 artist’s residency with Ellsworth Gallery until now, Chaz John’s work has consistently toyed with the upending of established hierarchies — whether animal or material — to arrive at a place in which the rez dog reigns supreme, placed on a marble pedestal,” Barry Ellsworth says.

The gallery’s second front-of-house show for the artist, the sequel presents a rich and dynamic development in plot and theme. “In addition to shifts in tonality and technique, John has increased the wide array of traditional media and approaches he employs,” Ellsworth says. “John’s work co-opts tropes of Western culture, often seen as empty symbols of class consumption, repurposing them in order to honor the rez dog. From the chiaroscuro and dynamism of his palette to the addition of gilded Rococo frames and ceramic figurines, John’s inspirations from the Western canon range from Caravaggio and through the Baroque, to the interior decoration of the landed gentry of British aristocracy.”

Beyond class and colonization, Ellsworth points out that John’s work raises other big questions, such as hyper-domestication: “The wild, free-roaming rez dogs have been adopted ‘in to the family’ to such a degree that they are ensconced in the most bucolic and genteel of settings. Yet the rez dogs in John’s largest canvases remain defiant, wild at heart. Neither wild nor pets, they are somewhere in-between. There is a push and pull of domestication at play that mirrors questions surrounding the dynamics of assimilation.”

The biggest question of all perhaps is the future that Rez Dogs II might portend. What might Rez Dogs III look like, Ellsworth wonders. The artist notes that his compositions have an oddly unpeopled post-apocalyptic air, which begs the question: Have the rez dogs assimilated to, and perhaps surpassed, the human?

We talked with Chaz John in advance of his Rez Dogs II exhibition.

Rez Dog Fights Turkey Vulture to Protect Fry Bread, 2019, acrylic on canvas, 66 inches by 60 inches.

Cowboys & Indians: How do you describe your work?

Chaz John: I’ve described it as “Indigenous poetry in the face of conflict.” It’s one of the few phrases I’ve ever coined that I thought fit well. I think work should be poetic.

C&I: What have you been working on recently?

John: Currently I’m hustling on my second solo show at Ellsworth Gallery called Rez Dogs II. It’s the sequel to the series I’ve been working on since my residency there last year.

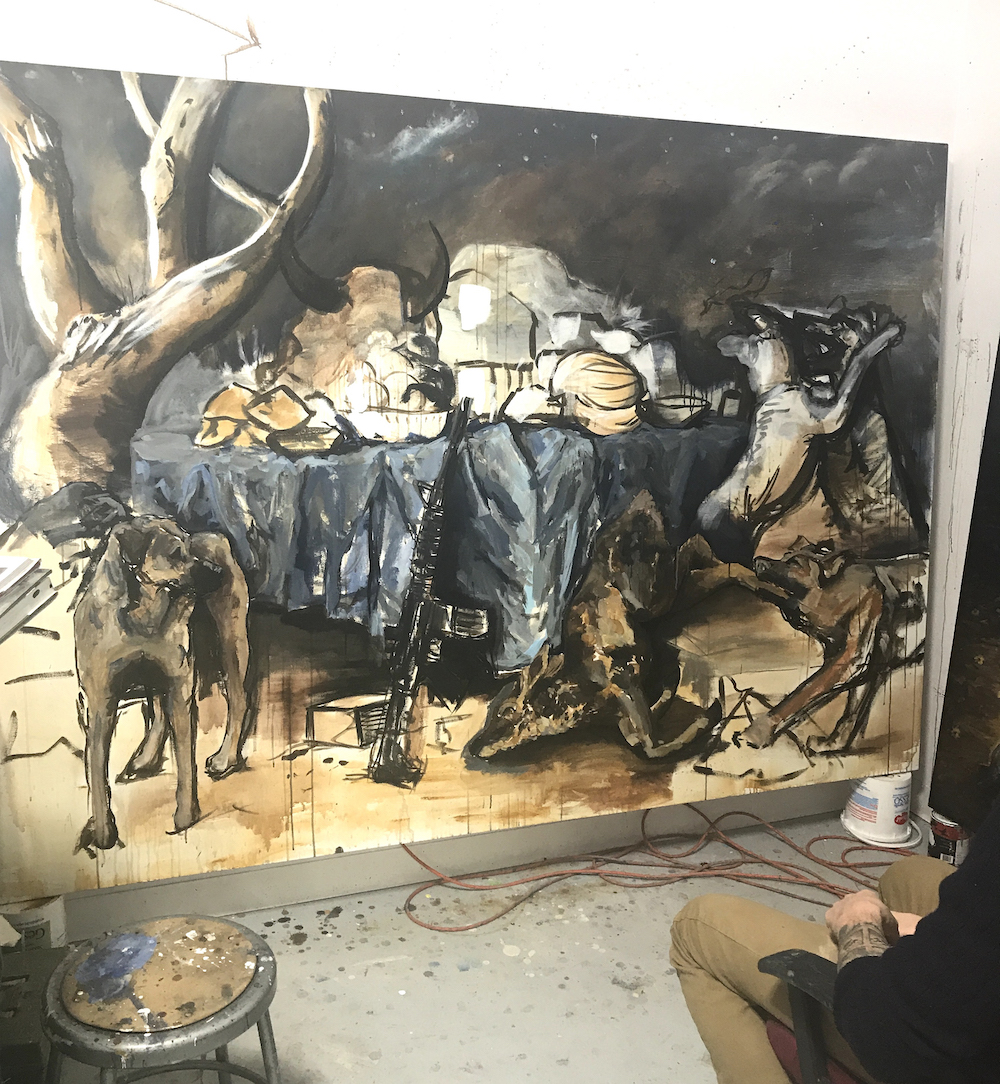

So far, the works have been developing a much richer and more dramatic color palette, and the compositions that are based on Victorian feasts and hunting scenes have become much more visceral with more surreal imagery than the originals. The paintings are also getting much bigger: Three of the works are roughly 6 feet tall and 8 feet long, which is the largest pieces for me on canvas thus far. I think there is something powerful about the size.

I’ve also been really getting into ceramics lately. I’ve been building different slip molds based on plaster dog figures I’ve found then combining them together with other casts of frybread and Victorian pedestals, all poured in porcelain, then painting them with china paint, really hitting that Victorian nail on the head. It’s something I’ve never really worked with before but really dig it.

C&I: How did you get hooked up with Ellsworth Gallery?

John: I was in a group show in the gallery called Nations and got introduced to Barry Ellsworth there. A little after that they offered me a position s artist in residence for two months for the first Rez Dog show, and I just recently signed on with them as an official represented artist.

C&I: Your subject matter for a while now has been rez dogs. Did you grow up with dogs? Why do dogs figure so prominently in your art?

C&I: Your subject matter for a while now has been rez dogs. Did you grow up with dogs? Why do dogs figure so prominently in your art?

John: I’ve always been a fan of dogs. I always had them around when I was younger. For this rez-dog project it really steamed from my own rez dog Eddy Spagetts. I think in a way I’ve been making work for him and other dogs I’ve had maybe. Also, the subject of animals can appeal to our most primal desire to understand something about our nature because animals can hold an indirect light to ourselves.

C&I: You’ve been quoted saying that your rez dogs are “painted in hues and values according to a dog’s visual spectrum, from black and greys to light blues and yellows. Hung low to the ground, their display caters completely to a rez-dog audience.” How did that perspective come to you?

John: I think I make stuff to entertain myself or what I want to see. I thought it would be funny to make work for a species other than humans. I had never seen anything like that before. I wanted to subvert the idea of who art is made for by making it for creatures that humans often think less of, in a space like an art gallery that is so steeped in elitism. And in this case these feral dogs are humanized and treated as heroic figures battling against the condition that they are set in, overcoming the negative odds of survival that was set in motion by humans.

C&I: I read you are interested in Victorian dog portraiture. Victorian style plus contemporary Indigenous makes for an interesting mashup. What is it that attracts you to Victorian dog portraiture?

John: A portrait of a dog is a very accessible image. It’s easy to understand and there can be as much allegory to it as you want there to be a lot of the time. I really like that it has these avenues.

You just can’t get more colonizing that Victorian stuff, and for me it’s a repeating symbol of occupation and its imagery.

I didn’t grow up on the rez, and generally consider myself a Native man who just barely skipped the bullet to full-blown colonization. My family and I would make visits to the rez on occasion, and the one thing I always remembered was the dogs there, running in packs.

And maybe this project is my own lens of those things.

2 Rez Dogs Fighting in the Kitchen, 2019, acrylic on canvas.

C&I: You’re from Topeka. Did you grow up there? What was your childhood like?

John: I did, yeah. I was born in OKC but moved to Topeka when I was 5. I’m a fan of Kansas, actually. Topeka has a certain greasy charm to it that I really appreciate, although a lot of those good spots have been closing down lately.

My childhood was pretty normal. Out in Kansas you really have to make your own fun, ya know, so I got really good at stuff like loitering.

C&I: When did you get into art? How did you learn to draw and paint?

John: I feel like I’ve always been drawing. It’s something I can’t really remember not doing actually. When I was young, I took all the art classes I could. My folks were super-supportive with it. I had some great teachers and classes, but I think for any skill like that you really have to branch out and start pushing and learning things on your own.

I still feel like I have a lot of learning to do actually, and a lot of times I feel like I’m just now learning how to properly lay down a formula for a good painting.

C&I: What was the first thing you created that really told you that you wanted to commit to a life of art?

John: I think, honestly, I’ve struggled to even call myself an artist for a long time. It even still seems like such an extravagant thing to me. I’ve gone through a lot of ups and downs with that specifically, and also some lost years in my life where I didn’t see art as being that important. I think only recently have I even begun to see a career as an artist and making work for the rest of your life can actually be an attainable goal. But one time I taxidermized a bird in a park in Chicago and some folks thought that was pretty good.

Rez Dog Mother and Puppies, 2019, acrylic on canvas, 60 inches by 66 inches.

C&I: Who have been your influences, inspirations, and mentors?

John: Well, influences right now for with this specific project I’ve been poring over — a lot of different Victorian animal artists like Edwin Landseer and artists like Frans Snyder. But as far as an overarching artistic influence, I really look [to] more comedic work and artists in that realm like Andy Kaufman and James Luna.

Art is so silly to me. I love work that can be seen though a lot of different lenses, like it’s either the most tragic movie you’ve ever seen or you can watch it as the funniest movie ever.

I’ve been very fortunate to have amazing mentors along the way, from the beginning with my childhood art teacher, Bob Ault, though high school, when Bova showed me that art school was a thing and really pushed me for it.

In college I had Mary Black Burn, who really drove home more conceptual concepts and how to really dissect work. And now Barry Ellsworth, the owner of the gallery, has become an amazing mentor for negotiating and navigating the art world as a newly emerging artist.

So, I’ve been very fortunate in that way.

In process in studio.

C&I: You are Winnebago and Mississippi Band Choctaw. How do you think your Indigenous roots and contemporary outlook inform how you walk in the world and how you create your art?

John: I think no matter what I make or do it’ll always come from a place of a mixed Indigenous man ’cause that’s who I am.

C&I: You’re just finishing up your studies at the Institute of American Indian Arts. What has school taught you about the practice of art?

John: IAIA is an amazing school and I’m a proud alum for sure. They really do a lot for their students in terms of supplying scholarship opportunities, random calls for art, and even showing student work at the museum level. I think most of all I’ve really learned to take advantage of all these opportunities and taking risks with throwing things out there.

C&I: And you’re in a remarkably creative setting. What about Santa Fe has been important to your art?

John: Santa Fe’s the most art-centered town that’ve ever experienced. People get really excited about it and there are a lot of folks making great work at a lot of different levels and markets.

C&I: Where do you paint and what kinds of circumstances and environment do you prefer to be creative?

John: I have a real short attention span and get distracted pretty easily, so I really have to isolate myself in the studio and basically block out the day to get anything done. I can work on emails or something else like that during the day, but I find when I really hit a stride and sink into that comfortable pocket of making work it has to be at night. Often to get anything done I feel really good about, I’ll work through the night, until the early morning.

C&I: How do you get your ideas?

John: I think that as artists we are constantly working, ya know? Even when I’m going down a rabbit hole of theories about cow farts at 3 a.m. I’m still actively thinking about, adding to, or generating new project ideas. I think that I try to make art as much as a 9-to-5 job as possible when I force my self to be in the studio, but it’s something for me that seems to never turn off.

C&I: What’s your process from idea to finished piece?

John: It varies from piece to piece. I really don’t consider myself a one- or two-medium artist. Even though I often include painting or drawing, they seem like they all are part of a bigger creature that is the work. So when I have an idea like this one and it requires me to learn how to work in ceramics, I’m relentless in figuring it out.

C&I: I’ve seen you described as an artist and an activist. I’ve been told that you were a medic at Standing Rock. How did that happen, and what was that like?

John: Sorry, I don’t feel like this is a relevant question to the project and respectfully don’t feel like disclosing my experiences there.

C&I: What makes you happy?

John: Weed, Star Trek, karaoke, throwing rocks at trains — things like that. I’m a pretty simple guy.

C&I: What’s a great weekend in Santa Fe?

John: I’m kind of a homebody man. I’m either working or struggling to sleep most the time. The rumor is Tiny’s is where it’s at for karaoke though.

C&I: Your show at Ellsworth Gallery coincides with Indian Market. What’s the best way to take in Indian Market?

John: There’s just so much going on — you just have to accept you’re never going to see it all. So winging it is probably the best option. I’d say bring your own pocket frybread cause the lines are long and its wicked expensive.

C&I: You think you’ll stay in Santa Fe?

John: I do for now. I’ve always been a fan of the desert, and so far Santa Fe and the area has really grown on me. There are a lot of artists doing great work out here. And the Indigenous art community is very strong. I feel that it has the potential to become an even bigger, more influential mecca for more progressive contemporary Indigenous art in the future.

C&I: Besides Santa Fe, what are some places and what are some experiences in the West that amp up your creativity?

John: I really pull creativity from everywhere — even those stranger experiences out here. One time I met this crazy Caddo lady out on a back road and she had probably 15 or so rez dogs with her in an RV truck. We ate some brisket and we talked about addiction for a while. When the dogs would wander off too close to the road, she’d call them all back with a shotgun. Maybe I’m making things for them too.

Rez Dogs II will be on view at Ellsworth Gallery in Santa Fe August 9 through September 2. Find more at ellsworthgallery.com and chazjohnart.com.

Photography: (featured) Rez Dog Mother and Puppies, 2019, acrylic on canvas, 60 inches by 66 inches/all images courtesy Ellsworth Gallery