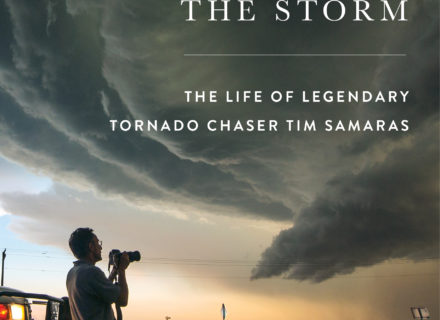

For his debut novel, Presidio, New York art writer Randy Kennedy comes home to his native West Texas with a tale of a philosophical car thief, his brother, and a stowaway Mennonite girl they accidentally kidnap.

Author Randy Kennedy has lived in New York City since 1991, where he worked at The New York Times as a clerk, then as a city reporter, and then wrote about the art world before taking a job at the art gallery Hauser & Wirth. His first book was Subwayland: Adventures in the World Beneath New York, a 2004 collection of his NYT columns about the characters and customs of the New York City transportation system.

His new book also depicts characters in a specific time and place — and form of transportation — but that’s where the similarities end. Presidio (Touchstone, August 2018) is a novel set on the highways, dirt roads, and roadside motels of 1972 West Texas. Troy, a car thief whose guiding philosophy is not to become attached to anything enough to consider it his own, reunites with his brother, Harlan, and accompanies him on a mission to track down Harlan’s wife and the money she absconded with. Joining them on their journey is Martha, an 11-year-old Mennonite girl who manages to hide, for a little while, from the two in a vehicle they steal.

The book is in a way a return home for Kennedy, who grew up in Yoakum County, Texas, near the border with New Mexico. He spoke to Cowboys & Indians about the book and his writing.

Cowboys & Indians: You’ve had a good career as a New York art writer, so this seems like an odd deviation in subject matter for your first novel. What sparked the idea for this novel?

Cowboys & Indians: You’ve had a good career as a New York art writer, so this seems like an odd deviation in subject matter for your first novel. What sparked the idea for this novel?

Randy Kennedy: I think I had always wanted to write about that part of Texas, where I grew up. Part of that was because I knew it pretty well. I moved to New York, and I started pretty quickly working for the The New York Times first as a clerk, then as a reporter. I’d always wanted to write fiction. Most of the things I were writing were character-based stories that happened in that part of Texas. I think when I first moved to New York, I really wanted out of Texas. I was a kid from a rural place, and I read a lot and knew that there was a big world, and I wanted really as far away as I could go. I didn’t want the next-biggest place in Texas, or the biggest place in Texas. I wanted out of Texas.

Once I moved to New York, that place physically in its landscape and geography loomed large for me. There were moments when I was homesick. But also, the more I read, the more I thought it would be interesting and powerful to set characters against that landscape. Part of that comes from westerns and McMurtry and western road movies and things like that. It just struck me, I guess, the juxtaposition between that place and New York further helped me understand how bizarre and unique it is, so I really wanted to set the first thing that I wrote in that part of Texas.

C&I: It started as a collection of short stories, right? What made you decide to make it a novel?

Kennedy: I always had it in a file under “Brother Stories” in my computer. They were almost all united by the character of this car thief. Sometimes it wasn’t the same guy, sometimes it was different car thieves, but it sort of jelled into this one car thief, and often it had to do with his relationship with his brother, who was kind of the good son to the thief’s Prodigal Son. Also, often these stories were written in first person, inside the head of this car thief. When there were a few of them, they began to work more and there was an almost-plot that kind of united them, I decided they made more sense as a novel. In a way, the journal entries, where Troy is talking to you in the first person, a lot of those are remnants of or whole pieces of short stories, those original short stories.

C&I: Was Martha, the Mennonite girl who joins them, kind of what made you see a plotline that connected the stories?

Kennedy: No, I knew part of the arc of the story, and I knew the brothers were going to go on this misguided attempt to find this woman, Betty, who had taken their money. And at some point I began to think that they needed somebody else in the car with them.

It wasn’t just because they were both taciturn, that they didn’t get along that well. It was more that I felt there needed to be somebody in the story who didn’t know either one of them and who they didn’t know. There was a thought of a hitchhiker, because it was in the ’70s. But then there was this idea because I grew up around Mennonites. I think some of them had ended up in that part of West Texas who had left colonies that are in the Chihuahua, Mexico. I had always been fascinated by that culture: their way of dress, their way of living. I started thinking about a Mennonite child who ended up being a girl. Part of that is thinking about Troy. He’s this person who’s had a breakdown and kind of detached himself from society. He’s a radically separated person, and I thought this girl coming from this religious society whose imperative is to separate themselves from society felt of a piece, even if they weren’t communicating that much, they would have some affinity.

C&I: I read that you looked at old car manuals and sales brochures to research the cars from that era. Did you talk to any car thieves, or did you have any experience at that — maybe from a bit of misguided youth?

Kennedy: No. One time I took my parents’ car without their knowledge or permission and drove to meet some friends in New Mexico and pissed my parents off, but I didn’t know any criminals. Dad was a telephone lineman and the son of a cotton farmer, and there were guys he knew who had maybe done some jail time, but they weren’t criminals. They were just characters. And to a degree, Troy is one of those, and the character who is his father, Bill Ray, is kind of one of those.

But I think my attraction, my interest in the car thief, came around because it kind of seemed like a pretty romantic figure in that part of the country, kind of a modern — I’ve said this in a lot of places, but it’s true — like a modern incarnation of a horse thief. You know, a horse thief was a pretty despicable western figure, and Troy is just really trying to cut all ties. It’s funny, I hadn’t read this before finishing the book, but I’m now on the subway reading Jean Genet’s The Thief’s Journal. You know, Genet was a pretty radical kind of thief, and he was really trying to cut all ties with conventional society. In a way, being a car thief is the same thing for Troy, just trying to cut all ties with respectable society. But also there’s something kind of romantic about being able to have any car you want and drive, just drive, drive, drive across the Texas Panhandle and have no responsibilities. I don’t know, for a long time, before I had anything coherent, I was just kind of taken with the idea of a car thief in West Texas.

Presidio is available at booksellers or through Amazon.

Photography: Marcelo Brukman