The tough-as-nails Wyoming lifestyle depicted in C.J. Box’s bestselling western novels is second nature to him, but he still actively pursues it for the sake of research.

Their footfalls hit the wood planks in a way that suggests the iconic third-act march of every brave cinematic lawman. Under a flawless blue sky, tourists walk along the boardwalk that lines the preserved Old West buildings of the Grand Encampment Museum in Wyoming.

An authentic blacksmith’s shop, ice cream parlor, log cabin, and other historic 19th-century buildings surround the museum’s guests. Visitors take photos with their phones and languidly pose in the shadows of the building’s classic Western false fronts.

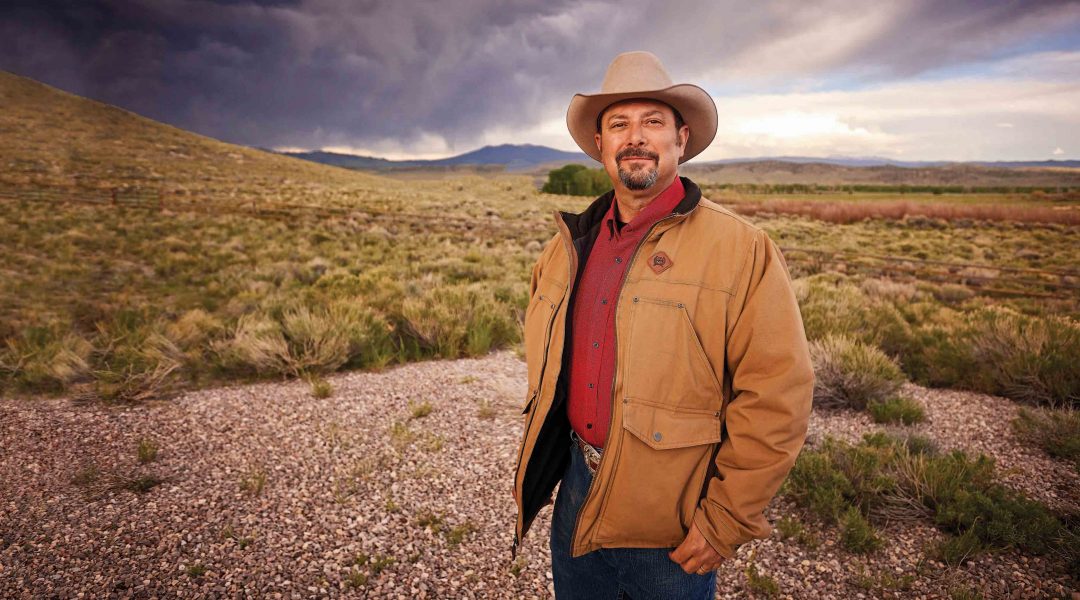

Yet those searching for authenticity in the modern West need to look no further than inside the museum, where C.J. Box sits at a table greeting groups of readers. The 59-year-old New York Times bestselling author chats, jokes, and takes selfies with those who come inside to meet him. Box has written 25 novels, many of which focus on the indomitable Wyoming game warden Joe Pickett.

Box is in grip-and-grin mode, wrapping up the end of his book tour for The Disappeared, Pickett’s most recent foray into the world of western crime. However, away from the crowds, Box is not unlike his famous protagonist: quiet, reflective, but quick to express profound appreciation for the vestiges of the American West.

It’s spring in Wyoming and the lush hills surrounding Box’s house roll away in all directions like a green sea. A white-toothed saw blade, the Medicine Bow Mountains stand in relief on the horizon. There aren’t many people in this part of the world. Wyoming is the least populated state in the country. But the people who live on past the fringe can sometimes be larger than life. Telling the stories of those real people has long been a passion for Box.

The author grew up in Wyoming, edited his high school newspaper, then went to the University of Denver on a journalism scholarship. His first job out of college in the mid-’80s was working for the The Saratoga Sun newspaper. He got that first gig after both his interview and fishing skills were put to the test while floating down a river.

“I drove up from Denver where I had just graduated, and I met the owner of the newspaper at a put-in, and we floated all the way to Saratoga, drank beer, and fished the whole way,” Box says. “By the time we got to town, I was ready to move.”

For three years he worked as the paper’s editor before starting an outdoor publication in conjunction with The Saratoga Sun.

“At the time, believe it or not, they didn’t pay much at the newspaper ... but there’s a lot of fishing in this area — so I would fill in at times for fishing guides,” Box says. “But those three years of working on the newspaper were probably the best on-the-job training I could possibly get for future books.”

As a journalist, Box got the chance to meet pretty much everyone in the Saratoga area where he now lives. “This area is very interesting. ... [W]orking on a little newspaper you talk to everybody, in every stratus, everyone from billionaires to survivalists — so I got ... a crash course in people and different attitudes that I still use today in the books.”

His novels are packed with descriptions of breathtaking vistas, the beautiful

but often cruel Wyoming weather, and a host of eccentric personalities. Box has garnered commercial success and literary praise, including the recent 2017 Spur Award for Best Western Contemporary Novel from the Western Writers of America.

By its creation, the American West is an amalgam of historic and modern quarrels. Each of Box’s novels addresses some theme or major political or environmental issue. “I come up with the issues first, whatever the issues are going to be, ‘the controversy,’ then research those things,” Box says.

Sometimes he arrives at a modern point of contention on his own and sometimes they appear from his readers — but whatever the source, he says he’s never lacking in material. “I keep files, clip files, and pull a lot of stuff off the internet,” Box says. “When it comes to those sorts of issues and controversies ... Wyoming and the mountain West are the tip of the spear.”

Conservation, energy, wildlife preservation, mineral extraction, tourism — the list goes on and on. Box says often an issue will take root in the West. “We’ve been talking about wilderness preservation and those kinds of controversies [such as] endangered species for years. ... [T]hey seem to come to a head here and then sort of spread out,” Box says.

When crafting the plot of his next story, Box says he starts with his chosen issues and lets the story naturally unfold from there. “I always start with ... an environmental or resource kind of thing, and I research the heck out of that until I’m comfortable with it,” Box says. “Sometimes I combine two or three of them — things that are happening in the West that make it grounded and interesting.”

One signature aspect of a C.J. Box novel is the plot’s unpredictability. It’s something Box takes particular pride in. If you think the story is going in one direction, it isn’t quite what you think, and sometimes he experiments with that assumption. “I don’t always try to have a big twist, but it just kind of occurs naturally, and sometimes the twist is that there’s no twist,” he says, adding the idea was to always keep the readers off balance. “Even through the entire series, Joe Pickett rarely dispatches the bad guy in a shootout; something else happens usually.” Which isn’t to say the villains in his books aren’t disposed of in spectacular fashion.

Box’s office is above a barn that houses his family’s horses. It’s a beautiful room, paneled in beetle-kill wood and filled with items that make the writer’s personal workspace unique. Box points to one wood panel near his desk that has a rifle bullet captured in the wood. It’s an unusual touch, but appropriate for the author whose books are filled with many similar details.

Box says researching his next novel is one of the most enjoyable parts of the writing process. “If Joe Pickett is going to do something like climb a wind turbine or go white-water rafting, I do those things. And if the location is going to be a specific place, I go there and put on my old reporter hat and just take notes and interview people.”

He enjoys being able to provide realistic but obscure details to his writing — nuances that add just the right amount of color to a scene’s description.

“There are too many writers that live in ‘writer world’ and all of their characters kind of have whimsical jobs that really don’t exist; and somehow everybody makes money but you can’t figure out how — and that always bothers me when I read those kinds of things.”

For Box, Wyoming’s mercurial weather is a regular character that’s almost as important as Joe Pickett, his family, or the eccentric falconer, Nate Romanowski.

“I think that [weather] affects everybody every day, and everything they do — especially a game warden. That’s got to be a huge part of every story. I think it adds a lot of nuances and a lot of character to the stories to have the weather, to have the thing end up in a spring blizzard — it just makes everything more difficult.”

Tony Hillerman, Larry McMurtry, Louis L’Amour: intentionally or not, western writers often find themselves the flag-bearers and spokespersons of the dwindling American frontier. Box is aware of his inherited responsibility regarding Wyoming and the West.

“That wasn’t ever the intention, but it has kind of worked out that way, and I don’t shy away from it,” Box says. “I had a background in marketing and tourism promotion, and that’s something I’m still very interested in and involved with.”

Being involved in tourism allows Box to view the West from the perspectives of those unfamiliar with it. “I was sort of able to see the mountain West through their eyes, and it opened my own eyes to a lot of things that I was used to — but didn’t realize how unique they were. I think that has really helped in the books in that I don’t take anything for granted or simply assume that readers know the area or know when elk season starts or how a little community reacts on the first day of hunting season.”

Even though Box’s stories are infused with the quick-draw culture and mythos of the Old West, he says he’s careful not to have stock characters, endings, and confrontations. He’d rather put a twist on the western and do away with the laconic boilerplate perceptions of the people who traditionally inhabit the genre. Box wants his characters to be realistic and modern. “It is too easy to create western stereotypes and have them all speak real slow and basically pretend that it is the 1880s,” Box says. “I’d rather not do that.”

While it varies, some of his novels are directly inspired by the events of the Wild West, such as in the second Joe Pickett novel, Savage Run, which was influenced by the real-world murderous stock detective Tom Horn. “Except it is modern-day industrialists hiring a hit man to get rid of prominent environmentalists. So that one was basically a retelling — other ones are and others aren’t. There’s one called Off the Grid later on that’s probably the most western of all the books — and it’s very high-tech.”

Box says that deep down, people are still drawn to the idea of the western. “It is on the edge of the frontier; people take justice into their own hands to a certain degree, they’re principled, and they’re sort of operating outside of civilization,” Box says. “They’re more independent, have more freedom, but at the same time are dealing with things by not necessarily calling the police, but by maybe dealing with it themselves. That still exists to a certain degree.”

The Disappeared debuted in April at No. 1 on The New York Times bestsellers list, proving Box’s point. “That shows this kind of thing has appeal beyond just the region,” Box says, “which always kind of amazes me.”

Find out more about the author at cjbox.net. Photography by Dave Neligh.

From the November/December 2018 issue.