After a successful run on the festival circuit, the impressive indie drama about a California rancher struggling to hold on to his land and his memories will kick off a theatrical run in November.

Veteran actor Perry King likes to joke that, after decades of work in film, theater and television, he’s achieved just enough fame to be a familiar face — but perhaps not quite a household name.

“Almost always,” he says, “what I get in public is, people come up to me and say, ‘I know you, what's your name?’ I’ll say, ‘Perry King,’ and they’ll say, ‘That’s it!’ Like I took a wild stab, and just happened to hit it.”

Don’t misunderstand: King is merely offering an observation, not issuing a complaint. At the ripe young age of 70, he can look back at a career abounding with enviable highlights: Co-starring opposite fellow up-and-comers Sylvester Stallone and Henry Winkler in The Lords of Flatbush (1974); playing major roles in movies as diverse as Mandingo (1975), A Different Story (1978), Switch (1991) and The Day After Tomorrow (2004); impressively portraying the attention-grabbing role of Col. Nathan R. Jessep during the original Broadway run of A Few Good Men; and appearing in well-regarded TV series and miniseries like Captains and Kings (1976), Aspen (1977), The Last Convertible (1979), The Hasty Heart (the 1983 drama for which he received a Golden Globe nomination); Riptide (1984-86), Melrose Place (1995), and Big Love (2010).

But here’s the thing: King isn’t looking back. Rather, he’s looking forward. In The Divide, his debut effort as a feature film director, he gives what arguably is his all-time best screen performance as Sam Kincaid, a Northern California rancher who, during the drought of 1976, struggles to remember what is important — and transcend what he cannot forget — as he is gradually diminished by Alzheimer’s Disease.

On the other side of the camera, King the director (working in concert with screenwriter Jana Brown) has fashioned an uncommonly compelling and emotionally rich drama, and surrounded King the actor with a sterling supporting cast: Bryan Kaplan as Luke Higgins, Kincaid’s hired hand, a man yearning for his own shot at redemption; Sara Arrington (of Amazon Prime’s Bosch) as Sarah, Kincaid’s estranged daughter, who’s reluctant to admit her feelings toward Sam or Luke; Luke Colembero as C.J., Sarah’s son, who desperately needs a grandfather and a father figure; and Levi Kreis (who earned a 2010 Tony Award for playing Jerry Lee Lewis in the original Broadway production of Million Dollar Quartet) as Tom Cutler, a deceptively charismatic fellow with a score to settle with Sam.

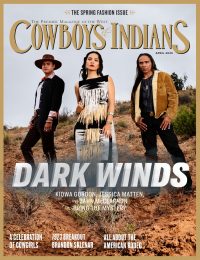

We caught up with King the morning after The Divide — which will screen Oct. 21 at the Wild Bunch Film Festival in Wilcox, Arizona, and kick off its theatrical run Nov. 9 — had its festival premiere at the WorldFest/Houston International Film Festival. Here are some highlights from our conversation.

Cowboys & Indians: It’s very unusual to shoot a movie in black and white these days. What made you think that was the right visual approach for The Divide?

Perry King: Like so many people, I’ve always dreamed of doing my own film. And it was always a black and white film in my head, because that’s what I love — that’s what’s always appealed to me. The old black and white films, those are what I love the most. Especially from the ‘30s and ‘40s.

But I have to say: If there was one film that I was trying to — well, I wouldn’t say copy, but perhaps extend out of — it would be Hud, which is a great film. And also Lonely Are the Brave, with Kirk Douglas. Which Kirk Douglas, I think, once said was his favorite movie. Those are western-themed, black and white movies. John Ford famously said, “Black and white photography is real photography.”

I can’t imagine [The Divide] being anything but black and white. And, really, I figured if I were going to make my own movie, I’d make it my way. For about 50 years, I’ve been working for other people. And you have to do it their way, because it’s their money, their choice. But you might find yourself thinking, “Well, if it were my choice, I wouldn’t do it this way. This is not the choice I’d make. But I’m doing your movie, so I got to do it your way.” But this time — I figured, I get to choose.

C&I: The black-and-white cinematography actually intensifies the idea that we’re looking at a landscape that’s been ravaged by drought.

King: It takes place in 1976, so it’s the last big drought in California before the most recent one. We actually serendipitously shot during what turned out to be the next big drought. We didn’t plan it that way, it just happened. We got lucky in that sense. But I have to tell you: At one point, we had to shut down a couple of days of shooting because there were so many fires around us. At another point, we were shooting on my land, and my house was a distance away — and I couldn't quite see my house. But there were so many fires around us, I thought, “I may not have a house tonight. It might be gone by the time I finish the day’s shoot.” That footage, by the way, we couldn’t use in color. It looks too bizarre. It’s like a weird yellow gray color in the sky. We could grade it and make it work on black and white, but not in color.

C&I: You give an extraordinary performance as Sam Kincaid, a man who’s straining to function as he’s obviously struggling with Alzheimer’s Disease. But you never specifically identify what’s causing him so much confusion and frustration.

King: Well, the movie’s about drought in many respects. Drought of the land, drought of your family and your personal life. And for this old man I play, drought of the mind. He’s experiencing early dementia. But, back in ‘76, nobody knew about Alzheimer’s, because the general public wasn’t familiar with the term. The diagnosis existed amongst doctors, but it was not publicly known. Even dementia really wasn't talked about.

As I recall, when I was a young man back in the ‘70s, the most people would talk about was senility. That’s the most scientific they got. Usually, what people would say was, “Oh, he's getting soft, he's losing it.” You were pretty much on your own back then. If you were experiencing memory problems, mental problems, early onset of what we now know is Alzheimer’s — back then, you were on your own. There was no sympathy, there was no support, there was no nothing. Not like if you had a broken leg, or you were paralyzed or something. No, it was dishonorable and almost immoral to have a failing mind. The finest people would be kind of — well, as I remember, almost abandoned because of that. I’m so glad to see we’ve made so much progress in that area.

C&I: When we first meet Sam — and for quite a while afterwards — he appears to have forgotten how to shave. Like, he’s kind of got a Willie Nelson thing going on there.

King: [Laughs] Yeah, for at least four months before we started shooting, I stopped tending to myself from the neck up, so I could become Sam, and live my character’s life. Sam just never looked at a mirror. Never cared. Everybody left him. His wife had died, his daughter had left him. He was all alone. He was tending his cows and trying to keep the place going in this drought. You know that scene where I cut my hair myself?

C&I: You actually look shocked when you finally do look at yourself in the mirror.

King: Yeah, because Sam hadn’t seen himself for years. He had no idea. It was like he’d been marooned on a desert island. He was shocked to see what he looked like. That scene was funny, because we had to construct the whole shooting schedule around it. Because once you cut your hair, well, that’s it. But I was determined to really cut my hair in that shot. We had two cameras on it. We just went for it.

C&I: It took years before you were able to get this labor of love off the ground. That must have been very frustrating for you as a director. But did it benefit you as an actor to have that long to work on your character?

King: This is the only time I’ve actually felt ready to go as an actor when we started. Every other job I’ve had… Well, look, right from the start, I remember finishing The Lords of Flatbush — this was around 1973 — and I remember very clearly thinking on that last day of shooting, “Good, I’m ready to begin.” I finally had done enough work so that I knew who my character was — and we were wrapping. Now, in this film, for the first time in my whole career, I thought, “I actually know who this guy is now.” So when we finally started shooting, I could do what you always want to do as an actor, which is kind of open the door in your head and say, “Go, Sam.” Sam would come out and do stuff I hadn’t thought of. Sam would wake up in the morning, and the first thing he’d do when he got out of bed was put his hat on. I didn't consciously think, “Oh, I should do that.” Sam did it. And I thought, “Of course, Sam would do that.” He lived for that hat. That hat was his identity.

C&I: You mentioned that you shot some of The Divide on your own land. Are you a rancher?

King: Yeah, I have a cattle ranch up in Northern California, a 500-acre place. Years ago, I did this movie with Sean Young, a TV-movie western called The Cowboy and the Movie Star, which was a nice, sweet film. And I loved the character I played, a guy who was getting divorced and was about to lose his cattle ranch because his ex-wife was going to take it. Sean Young was the movie star. She shows up and they meet each other and she ends up buying the ranch and giving it to him. They have a love affair and blah, blah, blah.

Well, like I said, I loved making that movie, just loved it. At the time, I owned a house and 40 acres up in this area of Northern California. I met this guy who had been a cowboy his whole life who was running cows on this chunk of land right by my house, 500 acres. He loves westerns, too, and he was the real deal. He taught me lots of stuff about real cowboying, little details that are so important. Like how you pony a horse, how you lead a horse, stuff like that. I put a lot of effort into learning how to be a real cowboy. And at the end of it, I thought, “I want to play this part again so badly.” But I never could get cast in westerns. Because when I younger, I was so damn pretty. Now, I could get away with it. But back then, people would never cast me in westerns. So finally, when this land came up for sale, right contiguous to my house, I thought, “OK, screw it. If I can’t play this character again — I’ll just become him.” And I did.