Contemporary clay artists carry forward an age-old tradition while breaking new ground.

The art world is increasingly viewing Native American pottery as a true American fine art, and not merely a craft identified by pueblo or family. Following in a long tradition that began with the utilitarian pot and evolved to heights of self-expression and creativity, contemporary artists are enjoying the freedom to fearlessly express their own artistic visions, layering traditional techniques, materials, and themes that connect the ancestral past and culture across the generations.

The legendary Southwestern Native potters always have been iconoclasts. Maria Martinez and Nampeyo each pushed boundaries of tradition with innovations in form and design. The finest artists continue to embrace a visionary future, exploring new techniques, materials, themes, and palettes while remaining faithful to the traditional ways of the clay.

Many of the top Southwestern potters working today are linked by family ties, tribal and cultural affiliations, and a deep commitment to passing along the traditions and techniques of their ancestors and instilling cultural pride in Native youth. They share the thrill of experimentation, the crushing devastation of a hand-coiled pot that breaks during firing, and the hard work it takes to excavate clays and polish large pots. They’re also receiving recognition and rewards as their work is increasingly sought by major art museums and collectors.

Les Namingha

In the world of Hopi-Tewa pottery, Les Namingha lets no one define him. “I started creating art with clay during summer breaks from college,” he says. “At the time, I was staying with my aunt, who became my teacher.” That would be the quintessential Hopi-Tewa potter Dextra Quotskuyva. “She provided spiritual instruction along with training in the use of native clays. Dextra was very creative in her designing and encouraged my own explorations.” His cousin Dan Namingha is also a respected contemporary artist, so “my family already had a presence in the art market, which was a blessing for me. Their insights definitely helped me establish my work as an artist.”

Namingha’s compositions blend modern art with Native designs. “Although I use some modern materials and firing methods, I still like to work with self-gathered clay. I also utilize ceramic glazes, but acrylic paint on clay is my main medium.”

Virtually every pot Les Namingha makes is a revolution in Native pottery. His works include traditional forms and designs harking back to his ancestor Nampeyo of Hano. Then, he veers into contemporary art with bright acrylic paints and designs that suggest Keith Haring. It seems like street artists might have burst into his studio, tagging the pots in his Urban series with cans of bright spray paint.

“The idea is about layering,” Namingha says. “Our existence involves layered experiences and memories. Graffiti is an example of layered ideas, as are ancestral sites where pottery sherds rest alongside exposed structures to create a unique visual and metaphoric abstraction. My work consists of layering Pueblo and modernist designs, which accentuate and flow with the shape of the vessel.” King Galleries, Scottsdale, Arizona, and Santa Fe.

Tammy Garcia

Tammy Garcia is from a family of legendary Santa Clara potters. As the granddaughter of Mary Cain and great-granddaughter of Christina Naranjo, she was perhaps destined to become a potter — after a teenage detour in beauty school. “I saw that the clay made my grandmother happy,” Garcia says. “It was cool to have her as a mentor. She taught me the importance of working hard for the best clay. Gathering clay was a family event. It’s easy to get the loose stuff, but you have to lay on your side and dig with a pick for the pure clay. I learned from them that quality is more important than quantity.”

She is inspired by the ancient pottery: “I can look at old pots and see their stories told in their pottery. Whether I’m working in clay, bronze, or glass, there is a story in the design and form.”

Pushing the boundaries of the medium, Garcia has created handblown glass sculptural works with glassblower Preston Singletary. “Glass gave me the choice of every color, beyond the clay sources on the land. My designs were sandblasted onto the vessels. I saw my piece in the hot shop blown in two hours. A coiled pot of the same size would take approximately four weeks to build.”

Her work continues to evolve as it is inspired by everything from antique brooches to wildlife. “The piece I am designing now has a trout. It is framed with bear claws and echinacea flowers.” Gallery Chaco, Albuquerque, and King Galleries, Scottsdale, Arizona, and Santa Fe.

Rainy Naha

Hopi-Tewa potter Rainy Naha’s precisely painted designs on brilliant white slips echo the traditional forms made by the women in her family, including her grandmother Paqua Naha. At the same time, Naha’s designs defy preconceptions of Hopi pottery. “I don’t mind when the blowing wind during firing brings a little blush color because sometimes people can’t believe my pottery is so white,” she says. “The white sandstone slip is gritty, and I hand-burnish with agate stones handed down from my grandmother. I also use Paqua’s painting palette that’s over 100 years old.”

Naha prefers a wild-spinach pigment, boiled to concentrate in a thick paint for her complex, intricate designs. “A pea-sized bit will paint 10 pots. I paint with a yucca brush with strands of little girl hair — my girls are young women now, so I don’t cut their hair anymore.” Adobe Gallery, Santa Fe.

Nancy Youngblood

Nancy Youngblood was surrounded by women potters at Santa Clara, but didn’t realize how important her family was. “Then I started watching. I would have lunch with my grandmother, Margaret Tafoya, and she began to share. She sat me down and told me that our family does it the old way. We dig our clay, we don’t use a kiln. We want to carry it on so the art won’t get lost in a hundred years. My grandmother once made me polish a piece eight times before she said it was ready to fire.”

Youngblood’s sensuous, melon-shaped pots with their play of light and deep, polished ribs, beg to be touched. “My great-grandmother Sara Fina Tafoya put a swirl on the top of her water jars that caught my eye. I decided to carry the rib below the center of the piece, or the rainbow band. It’s visually appealing and technically challenging. It looks incredible when it comes out. But, I’ve gotten down to polishing a couple of single ribs on a 64-rib piece, and it fails. When that happens, I don’t want to make another anytime soon.”

But she does. Her 46-year career is filled with magnificent pots. Recently, Youngblood successfully fired a 128-rib piece. A collector present at the firing bought it on the spot. “I don’t want to keep doing the same thing. I want new challenges. I’ve spent the majority of my life doing what I love. I always remember: Make something that you love, because if it doesn’t sell, you’re going to be living with it!

“My grandmother asked me how many ribs I could polish at once. I said three. She said, ‘I think I could make that, but I couldn’t polish it.’ It was the best compliment I ever received.” King Galleries, Scottsdale, Arizona, and Santa Fe.

Juan de la Cruz

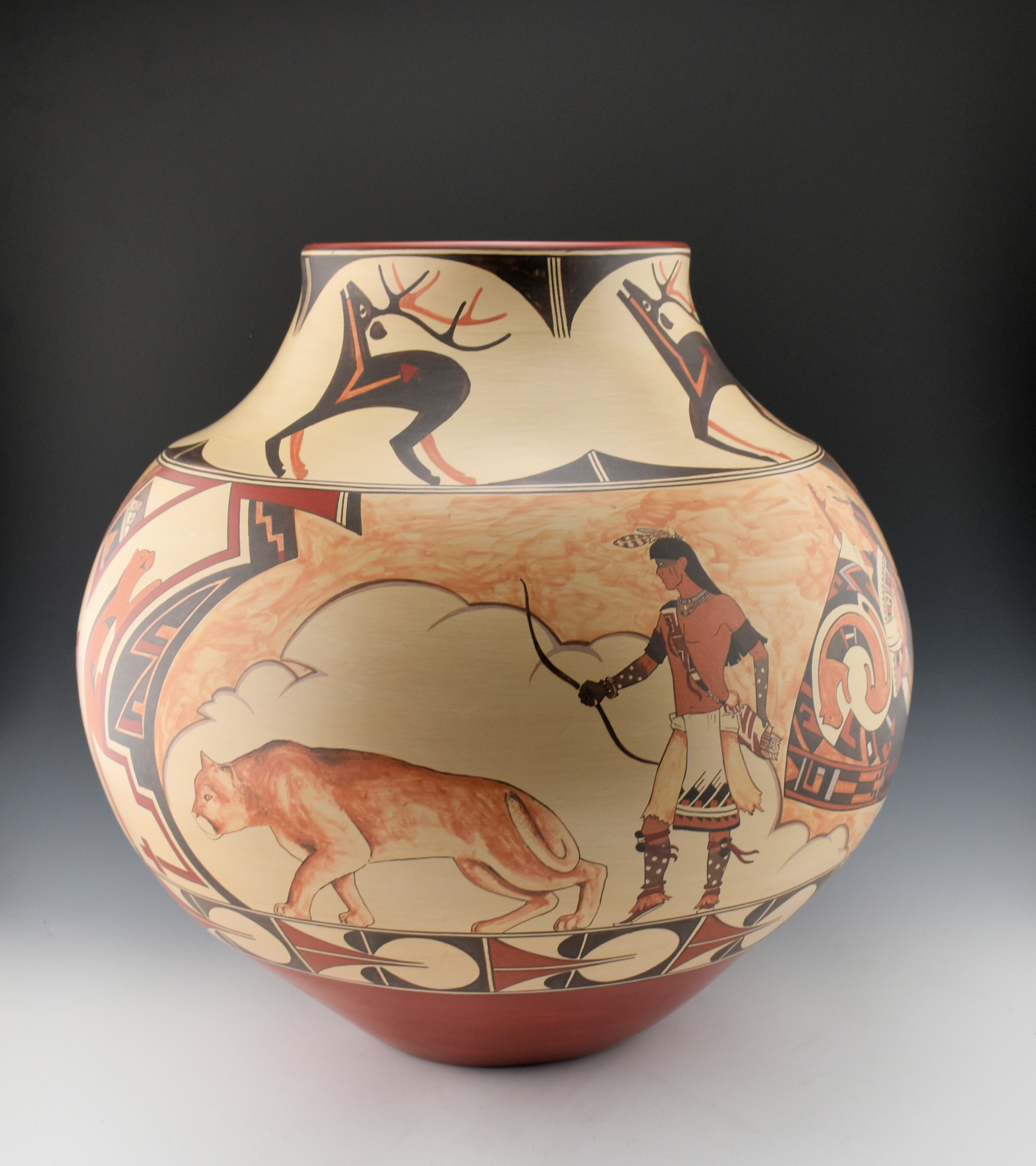

Juan de la Cruz of Santa Clara is catching the eye of collectors. When his mother, Lois de la Cruz, saw his watercolors, she suggested he paint her pots. “She told me to think of it as watercolor at 1,000 degrees.” He continues to benefit from her guidance. “The clay pigments are very different; my mother showed me and taught me how pigments can misbehave in the firing process.”

De la Cruz, whose father is painter Derek de la Cruz, works in the Santa Clara home his grandfather built, using traditional subjects and stories, often combining imagery from Greek mythology with art deco influences from Erté. His fine and flowing lines freshly interpret the old designs through a fine-art lens. He recently began coiling and firing his own pots.

“I’m constantly learning,” De la Cruz says. “I draw from the ancient kiva murals, but I’m not interested in making carbon copies of old designs. I love rendering the human form.” King Galleries, Scottsdale, Arizona, and Santa Fe.

Jennifer Tafoya Moquino

Santa Clara Pueblo potter Jennifer Tafoya Moquino is the daughter of Kiowa-Pueblo potter Emily Suazo-Tafoya and great-granddaughter of Severa Tafoya. Jennifer’s father was pottery innovator Ray Tafoya, who was known for his incised miniature pottery with used Mimbres designs highlighted by additional clay slips.

In her own work, Moquino is known for precise sgraffito (shallow carving), notable not just for its fine detail but also for its vivid color. She collects and processes all of her materials from natural source. Using traditional methods of hand-coiled pottery, she shapes, polishes, and traditionally fires her pieces. Incising her designs, she then applies natural ore colors and slips.

Imagery of fish, birds, and other wildlife merges an Asian design aesthetic with traditional Santa Clara geometric motifs and symbols, using natural slips and pigments on her imaginatively formed pots — and earning numerous awards, including at Santa Fe Indian Market and the Heard Indian Market.

Collectors prize her unusual, detailed, highly realistic animal images and figurative works. “There are cultural and artistic similarities with the dragon and the water serpent, with water and the koi fish,” Moquino says. “I started with animal figures; I could do them all day long. I’m also making more traditional pots and leaning toward the Santa Clara traditions now that I’m collaborating with other potters.” Native American Collections Gallery, Denver.

Virgil Ortiz

Carrying on the Cochiti tradition of social commentary, internationally renowned ceramicist, fashion designer, and graphic artist Virgil Ortiz, from Cochiti Pueblo, New Mexico, explores taboo subjects. “When I was a kid, I sold pots to buy Star Wars figures. Art dealer Robert Gallegos in Albuquerque showed me the 19th-century Cochiti figures that satirized tourists. That is what I was doing and I never realized it.”

His work uses contemporary art to blend historic events with futuristic elements. One historic event that has captivated his creativity for decades is the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, when Native Americans rose up and expelled the Spanish from 1680 to 1692, exploring the pivotal events of the revolt via video, storytelling, dozens of ceramic figures, music, photography, and a screenplay incorporating history and science fiction, Ortiz created the masterwork Revolt 1680/2180 as part of his “mission in life ... to tell the world about the Pueblo Revolt. Europeans know about the Pueblo Revolt, but Americans don’t.”

For Ortiz — who has fashion lines, glass arts, and a jewelry collection at the Smithsonian — no subject would seem to be off-limits. His figurative works explore themes of bondage fantasies and gender identity, with images of Boy George, RuPaul, and We’wha, the famous 19th-century Zuni Ilhamana who combined male and female traits as the embodiment of the mixed-gender role of the “Two-Spirit.”

But for all the mediums he excels at, the clay work, Ortiz says, “is the heartbeat of everything I do — everything revolves around it.” For his latest project, the exhibition Revolution, he’s interpreting the characters in a variety of media. “I am doing life-size versions like the terra-cotta warriors of China.”King Galleries, Scottsdale, Arizona, and Santa Fe.

Al Qöyawayma

Hopi potter Al Qöyawayma, or Al “Q,” as the former engineer is fondly called, combines figurative repoussé sculpted reliefs with traditional coil construction and stone-polished surfaces that conjure the ancient architecture of the Colorado Plateau. His subtle polychrome and deep reliefs are meticulously executed. “I like the way the sunlight produces ever-varying shadows on the piece as the day goes by, just as in a structure,” he says.

Born in 1938, Qöyawayma is a descendant of the Coyote Clan that occupied the village of Sikyatki near First Mesa. He learned basic techniques from his aunt Polingaysi (Elizabeth White), who utilized repoussé, pushing designs out from the inside, and who was known for her corn design.

Building on that, he studied the collections in the Smithsonian Institution. “I was most interested in the three-dimensional aspects of the design, or designs defined by beautiful polychromes.”

The migration of ancient peoples across the Southwest fascinate Qöyawayma. He has studied archaeological sites in Arizona’s Jeddito Valley and the kiva murals of sites such as Awatovi on the Hopi Indian Reservation in Arizona and Pottery Mound in New Mexico. “The architecture is the tip of the iceberg,” he says. “You can’t see what lies beneath.”

Education is another passion. “My aunt always told young people to go out and learn,” says Qöyawayma, who cofounded the American Indian Science and Engineering Society. “The foundation is in parents, the home, and Hopi culture, but do not fail to take the best of other cultures. I am in the fortunate generation that worked with Allan Houser, Lloyd Kiva New, and Charles Loloma in rebuilding IAIA [The Institute of American Indian Art].”

Awarded “Best of Pottery” at both the 2016 Santa Fe Indian Market and the 2017 Heard Indian Market, Qöyawayma has continued creating well into his 80s, giving thanks to the Creator and to his clay for giving him an artist’s life. King Galleries, Scottsdale, Arizona, and Santa Fe.

From the August/September 2018 issue.

More From The August/September 2018 Issue

25 Things That Shaped The Western

Bridges On Birmingham

The Iroquois White Corn Project