Here are the moments, people, and events that made the Western movie genre what it is today.

We’ve got to agree with writer John R. Milton: “The Western seems to explain to us something about ourselves and our dreams, on both a personal and a national level.”

It’s not simply that we enjoy westerns more than gangster movies or musicals; it’s that they resonate in a deeper way, by connecting us to our national heritage and our forefathers. They give us history to experience, heroes to admire, and stories to treasure.

Americans loved western tales long before the invention of the movie camera. Our fascination with the frontier dates back to the era when explorers and pioneers first began taming the territories that were connected to our new nation but not yet part of it.

These are some of the historical and cultural events that shaped the development of the western and upraised it into our national genre.

1. Columbus and the Horses (1492)

Most schoolchildren are still being taught that Christopher Columbus found a New World while trying to sail for India. During his subsequent trips to the islands around the North American continent, he brought with him one of the essential elements of every classic western: horses.

2. Manifest Destiny (19th century)

From the time the original colonies were settled, there were those curious to know what lay beyond the borders of the new nation. Expeditions that went west to explore the wilderness came back with maps, paintings, and fantastic tales. The American fascination with those early pioneers, explorers, and frontiersmen — and the widely held 19th-century belief that settlers were destined to expand across the continent — inspired a market for stories about their adventures.

3. The Leatherstocking Tales (1823 – 1841)

In pathfinder Natty Bumppo, author James Fenimore Cooper created one of the best-known characters in world literature, and the archetype for the western heroes featured in dime novels, pulp magazines, and, eventually, the movies.

4. The First Dime Novel (1860)

In 1860, publishers Erastus and Irwin Beadle released a novel entitled Malaeska: The Indian Wife of the White Hunter. It sold more than 60,000 copies within a few months, launching the dime novel as a vehicle for popularizing legends and folk heroes of the West.

5. Wild Bill (1867)

In this article published in Harper’s magazine, author George Ward Nichols describes a walk-down gun duel between James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok and Dave Tutt in the public square in Springfield, Missouri. In doing so he invented the “showdown” that gave countless films and shows an exciting final act.

6. The Gunfight at the OK Corral (1881)

The most reliable historical sources say it was over in less than a minute. On October 26, 1881, months of escalating tensions between a band of outlaw cowboys and the Earp brothers were settled in Tombstone, Arizona. It’s arguably the most famous moment in the history of the Old West, one that created heroes and villains from real life, not myths and legends — even if that’s what they became eventually. It also provided the subject for several classic westerns, including Frontier Marshal (1939), My Darling Clementine (1946), Gunfight at the OK Corral (1957), and Tombstone (1993).

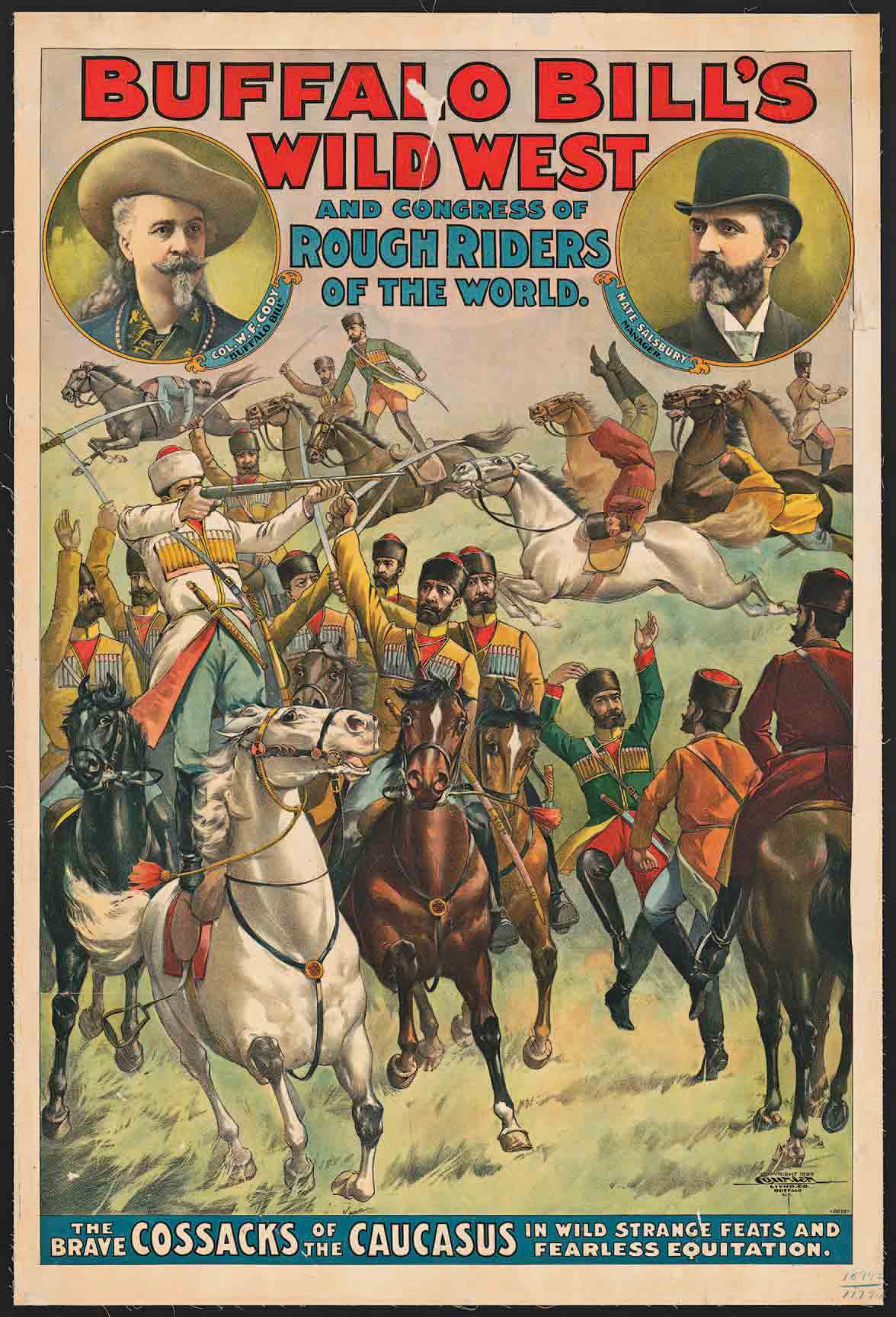

7. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show (1883)

Reading about thundering hoof beats and Indian attacks and Western sharpshooters was one thing, but showman William “Buffalo Bill” Cody brought those spectacles to life in a traveling cavalcade that played for three decades to capacity crowds around the world. Seven acts from the show were filmed by Thomas Edison in 1894.

8. The Virginian (1902)

It’s debatable whether Owen Wister’s novel The Virginian: A Horseman of the Plains became the model for the western as we came to know it, but it achieved a level of popularity and critical acclaim that far surpassed other western stories of its day. The book sold more than 1 million copies by 1920; was adapted into a stage play, a television series, and a musical; and was filmed six times. Gary Cooper became a star when he played the title role in the 1929 version, which also featured the first line of dialogue from a western to make any list of great movie quotes: “If you want to call me that, smile.”

9. The Great Train Robbery (1903)

The first western movie craze was ignited by a 12-minute film shot in New Jersey by Edwin S. Porter. Inspired by an 1899 train robbery committed by Butch Cassidy, Porter dazzled audiences with shootouts and chase scenes unlike anything they had seen before — all on a $150 budget.

10. Henry Writes The Caballero’s Way (1907)

As created by author William Sidney Porter (O. Henry), the Cisco Kid was a quick-tempered desperado who killed for sport. When Warner Baxter played him in the first talking western (1928’s In Old Arizona), his transition to a more heroic persona was already underway. Baxter won the Oscar for his performance and would play the Kid four more times before turning the role over to Cesar Romero, Gilbert Roland, and Duncan Renaldo, who brought the character to television in a 1950 – 56 series that aired in syndication for decades.

11. Broncho Billy (1909)

The movies’ first cowboy hero was Gilbert M. Anderson, known to audiences as Broncho Billy. Between 1909 and 1915, Anderson made around 300 westerns, establishing the cowboy as a marketable movie star.

12. John Ford Meets Marion Morrison (1927)

Today we can’t imagine the western without John Wayne, but the actor’s journey to icon status might not have launched had it not been for a chance meeting on the Fox Studios lot. Twenty-year-old USC student Marion Morrison was working part time as a prop man when director John Ford noticed him and expressed an admiration for the young man’s toughness and tenacity. The friendship formed that day would eventually produce some of the best westerns ever made.

13. The Covered Wagon (1923)

Though largely forgotten now, The Covered Wagon was the most popular film of 1923 and is regarded today as the first epic western. Its commercial success resulted in Hollywood’s tripling western production just one year after its release.

14. Cimarron Wins Best Picture (1931)

The Academy Awards were not yet 5 years old when Cimarron (1930) was named Best Picture. It didn’t start a trend. But its victory was forced to carry the Oscar banner for westerns until the 1990s, when the Kevin Costner epic drama Dances With Wolves won Best Picture in 1991 and Clint Eastwood’s more traditional shoot-’em-up, Unforgiven, took the trophy two years later.

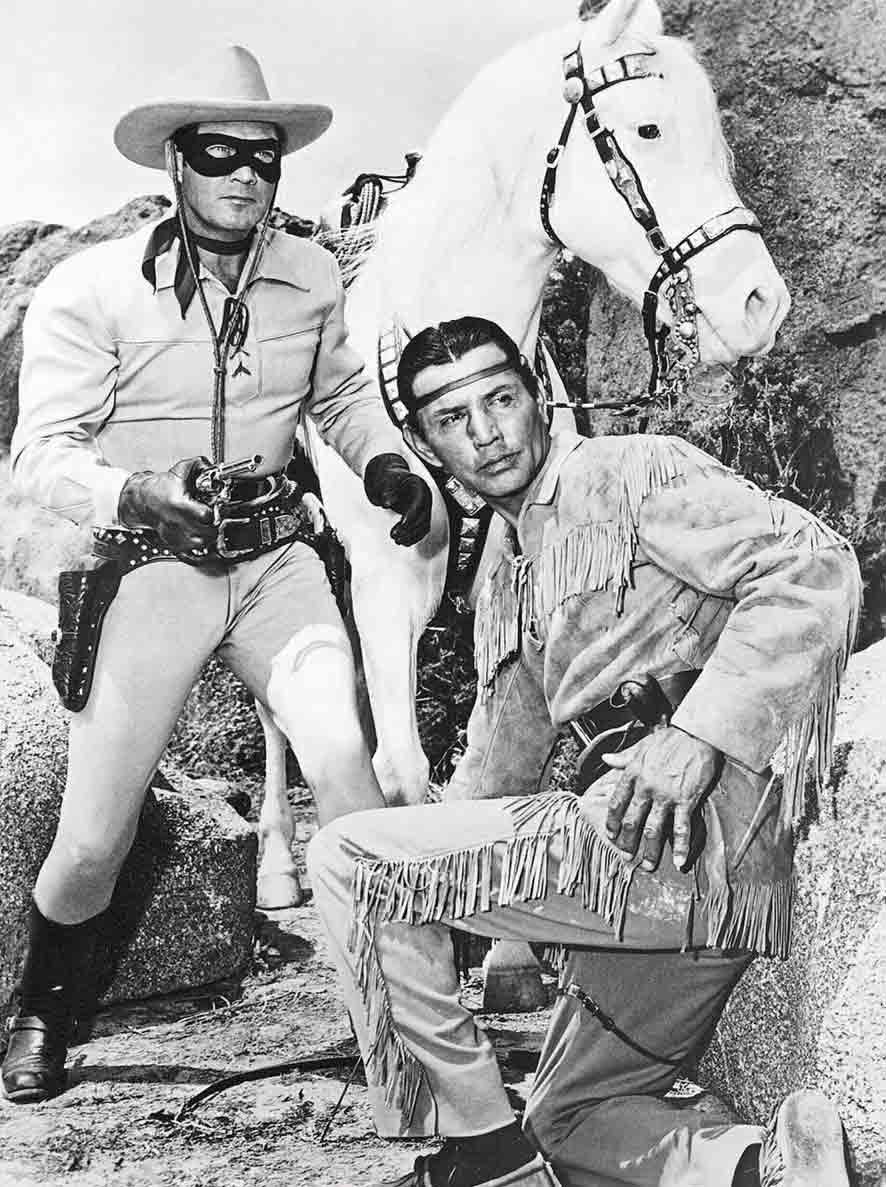

15. The Lone Ranger (1933)

Debuting in a radio series aired on WXYZ in Detroit, the adventures of the Lone Ranger and Tonto would be featured in films and serials, on television, and in comic books, with the masked rider of the plains becoming the personification of the morally upright heroic cowboy. The portrayals by Clayton Moore and Jay Silverheels in the 1950s remain definitive.

16. In Old Santa Fe (1934)

One of the most delightful and enduringly popular western subsets is the singing-cowboy movies that flourished from the 1930s to the 1950s. Their first star was Gene Autry, who made his film debut in In Old Santa Fe. He appeared in more than 90 films, sold more than 100 million records, and paved the way for other singing cowboy stars, including Roy Rogers, Tex Ritter, Eddie Dean, and Rex Allen.

17. Stage to Lordsburg (1937)

Among western writers, Ernest Haycox was celebrated for his attention to historic detail and his creation of psychologically complex characters. With his short story “Stage to Lordsburg,” which ran in The Saturday Evening Post, he broke new ground by upending the cliché that the towns and outposts of the West were the only admirable bastions of civilization. In this story the settlements are as corrupt as the frontier, which is why Dallas and the Ringo Kid prefer to stay outside their borders. The film version, Stagecoach (1939), was equally groundbreaking for the quality of John Ford’s direction, for its Monument Valley setting, and for reintroducing John Wayne to movie audiences in a star-making role. Writes The Motion Picture Guide, “This western eclipsed all films in the genre that had gone before it, and so vastly influenced those that followed that its stamp can be found in most superior westerns made since Ford stepped into Monument Valley for the first time.”

18. Harry Goulding Goes to Hollywood (1938)

We can thank Monument Valley resident Harry Goulding for helping to shape America’s vision of the West. When he heard United Artists was looking for a place to shoot a western, he brought photos of the area to the studio. Goulding didn’t have an appointment but refused to leave until someone saw him. Eventually someone did, and when John Ford laid eyes on the photos he knew he had his location for Stagecoach. The director would make seven films in Monument Valley over the next 25 years. Today, no other region is more closely associated with the western genre.

19. Anthony Mann Meets James Stewart (1950)

In 1950, James Stewart was already a cinema icon after starring in such classics as It’s a Wonderful Life and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. But a series of post-World War II flops, and a desire to take on more challenging roles, led him to film noir director Anthony Mann, also eager for a new challenge. Together, they made a series of classic westerns: Winchester ’73 (1950), Bend of the River (1952), The Naked Spur (1953), and The Far Country (1954) that revived Stewart’s career and added darker hues to his everyman personality.

20. Honoring Native Americans (1950s)

Westerns featuring sympathetic portrayals of Native Americans date back to the silent era. But these were exceptions until the 1950s, when films such as Comanche Territory (1950), Apache (1954), White Feather (1955), and Run of the Arrow (1957) established a more compassionate perspective that informs such later classics as John Ford’s Cheyenne Autumn (1964) and Dances With Wolves (1990). The change coincided with a renewed interest in ethnic literature and the plight of minorities following World War II.

21. Shane and the Twilight of the Gunfighter (early 1950s)

The gunfighter in a typical western was a figure to be challenged, feared, or revered. Classics like 1950’s The Gunfighter (Gregory Peck) and 1953’s Shane (Alan Ladd) popularized a new perspective: the quick-draw hero as a man out of time, as civilian law began to displace frontier justice. The plight of mavericks in a changing world still surfaces as an American theme, while also adding a new dimension to several classic westerns from Lonely Are the Brave (1962) to The Shootist (1976).

22. Seven Men From Now (1956)

Next to John Wayne, the most iconic star of the western genre is Randolph Scott. He affirmed that legacy through five films made with director Budd Boetticher and writer Burt Kennedy, beginning in 1956 with Seven Men From Now. Scott, then 58, established his most enduring screen persona in these stark B-movies, each shot in about two weeks.

23. Westerns Take Over Television (1958)

The success of such weekly western radio shows as Gunsmoke with William Conrad and The Six-Shooter with James Stewart encouraged television to embrace the genre. By 1958 there were scads of western series vying for viewers, from classics like The Rifleman and The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp to long-forgotten misfires like Rough Riders and Jefferson Drum. Television also created a new audience for the B-western features from the 1930s starring Ken Maynard, Bob Steele, and Hoot Gibson.

24. A Fistful of Dollars (1964)

Traditional westerns did not fare well amid the political and civil unrest of the 1960s. But these turbulent times inspired a new vision of the West coming from Europe, envisioned by directors like Sergio Leone. Critics dismissed them as “spaghetti westerns,” but the films, beginning with A Fistful of Dollars, struck a chord with audiences, who suddenly found it more difficult to tell the good guys from the bad.

25. Survival Mode/Long-Awaited Renaissance? (1980s – present)

By the 1980s westerns were rarely produced, despite enjoying great success when they were done right. Lonesome Dove (1989) was heralded as a landmark television miniseries but failed to inspire a new wave of western productions. The Best Picture win for Unforgiven (1992) also didn’t trigger a genre revival.

But the western will survive, as long as actors like Tom Selleck and Sam Elliot continue to support the genre, shows like Deadwood and Justified and Longmire find an audience, and filmmakers want to put their own spins on classics like 3:10 to Yuma, True Grit, and The Magnificent Seven.

It will survive because it will always be part of our national mythology. And because new talents like Taylor Sheridan (Hell or High Water, Wind River, Yellowstone) appear on the scene with contemporary stories set in the West that expand the boundaries of the genre. But most of all, the western will survive because there will always be those storytellers who would have us look back to a time when — to paraphrase Gene Autry’s Cowboy Code of the West — cowboys worked hard; always told the truth; were kind to small children, old folks, and animals; and never betrayed a trust.

From the August/September 2018 issue.

More From The August/September 2018 Issue

Bridges On Birmingham

The Iroquois White Corn Project

Gil Birmingham