The Santa Clara Pueblo artist’s compelling clay figures reflect our shared human experience.

Contemporary Santa Clara Pueblo ceramic sculptor Roxanne Swentzell smiles at the conundrum presented by her hand-formed clay chess set. How do you play chess when all the figures on one side are male — a king with his bishops and warriors, and pawns consisting of man-made inventions like the airplane and cannon — facing off against the female elements in life? Across the chessboard the queen/mother holds her infant. She is flanked by wise crones and fierce women warriors, and fronted by pawns representing clouds, storms, and emotional states.

But rain can be either life-giving or enormously destructive; technology can be helpful or cause unspeakable harm. Men can play beautiful music and women can fight. Swentzell’s chess game “could bring out the anger and struggles we have with each other, but the weird thing is you have the feeling the king and queen should be partnered and the crones and old wizards should be partnered,” she says. “They’re natural partners, yet they’ve gone into this gap state, which is sad.” Sweeping her hands as if mixing chess pieces on a board, she imitates the players’ potential response: “Let’s just rearrange all this!”

That’s what the 55-year-old award-winning artist would like to do with much of the world these days. Barring that, Swentzell nudges perceptions and paradigms on a more intimate scale, creating powerfully expressive clay figures ranging from chess-piece size to monumental, some produced in bronze limited editions. They are part of her ongoing attempt to shift, if not the world, at least individuals’ perspectives and hearts.

Born into a culture whose traditional beliefs emerge from a concept of balance, she has lived in two worlds and balanced seeming opposites all her life — and translated those experiences into thought-provoking, smile-inducing art.

Swentzell, her long, braided black hair graying at the temples, sits at a sturdy wooden kitchen table with wide wooden benches. She speaks in a warm, straightforward manner, her brown eyes crinkling at the corners when she smiles. The serene adobe house, which she built at Santa Clara Pueblo in northern New Mexico, is as expressive of the artist as are her sculptures. One earth-colored hand-plastered living room wall features a 6-foot-long reclining clay woman in bas-relief. Hand-built kitchen cabinet doors are adorned with bas-relief terra-cotta faces, each with a different expression. Outside, where once there was nothing but bare dirt, a small grove of tall bamboo proliferates among a lush diversity of greenery, all planted by hand. Just beyond a koi pond and fountain, chickens, turkeys, and goats mill around in their enclosures.

It’s an oasis of sustainable living that Swentzell, now 55, began creating in her early 20s. By then she had already spent two years studying ceramic sculpture at the Institute of American Indian Art in Santa Fe, having been granted early admission as a teen. She’d followed that with a year of European-American art instruction at the Portland Museum Art School in Oregon, lived briefly with her first husband in the mountains of northern New Mexico, and given birth to her son and daughter. Although she was raised primarily in Santa Fe, where her New Jersey-bred father was a scholar, teacher, and philosopher, settling at Santa Clara Pueblo felt like coming home. It’s the ancestral place of her mother’s family, and its age-old cosmology counterbalances the artist’s life in contemporary American society, underpinning and informing everything she does.

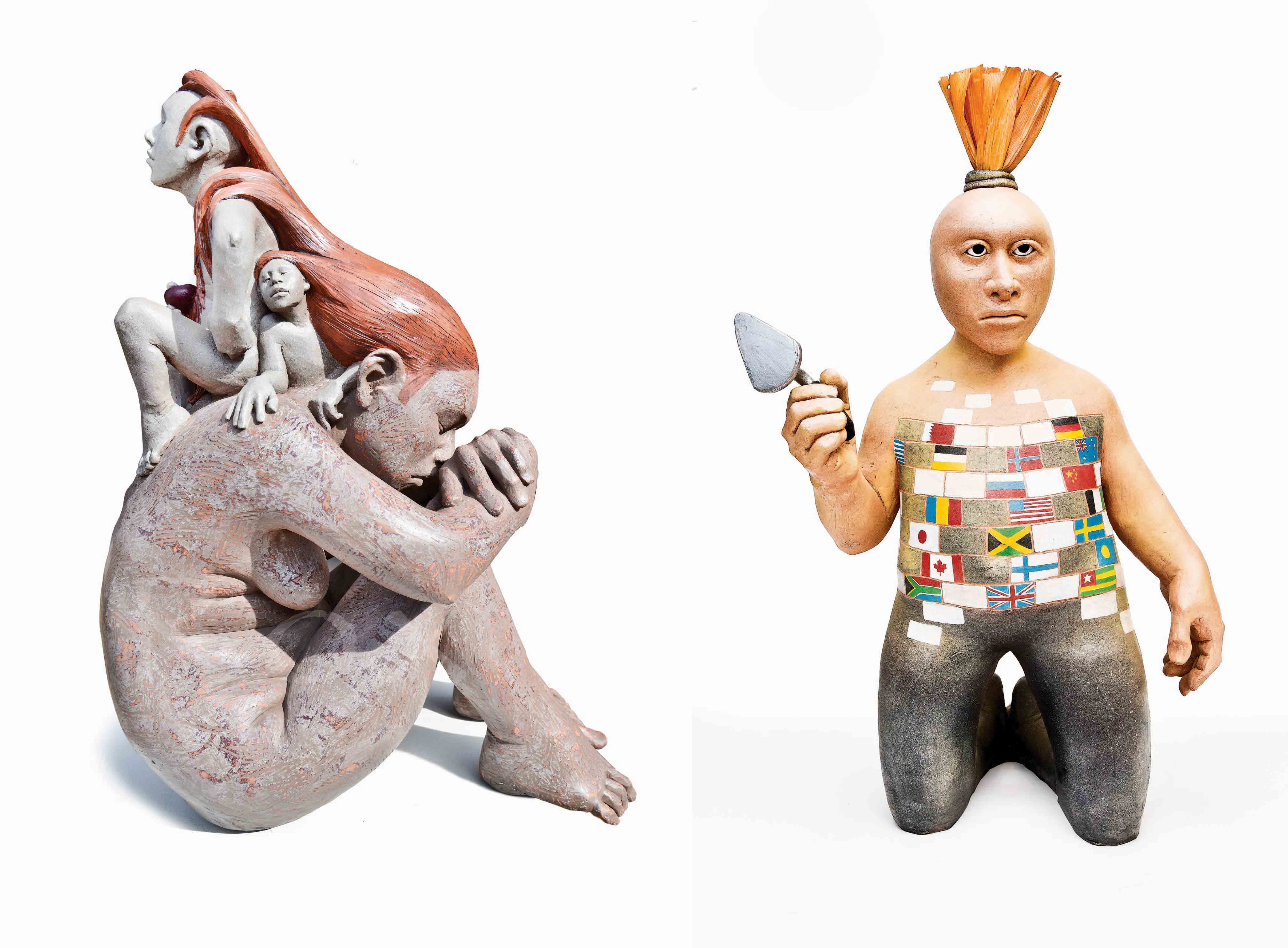

In clay, which for Native people represents the sacred earth, that means works like Sitting on My Mother’s Back. A proud, arrogant figure holding an apple is perched on the back of his sad, hunched mother, the Earth. Another, smaller figure is half-hidden behind him. Both drape their mother’s hair over themselves as if it were their own, with no concern or acknowledgement of how the Earth might feel about constantly being sat upon and used.

Yet even when addressing serious issues, Swentzell frequently uses humor to make a point. Trump Trump — the title’s first word is a verb — represents a koshare, the sly, provocative Pueblo trickster clown whose role it is to point out things people need to know about themselves. In this case the koshare sports orange-dyed corn husk hair and a shirt covered with flags from around the world. He holds a spade, preparing to build a wall to keep out everyone represented by those flags. Swentzell notes that from a Native American perspective he is declaring, “You want to talk about outsiders? Let’s talk about outsiders. I can outdo you!”

In all of Swentzell’s work, facial expressions, body language, and gestures instantly and wordlessly convey feelings that virtually anyone can understand, regardless of nationality or culture. Full Circle, for example, is a tender portrayal of a seated woman hugging a baby, and the baby hugging back. It reflects the artist’s experience when she holds her youngest grandchild. “It feels like the circle of life completing itself through generational love — grandmother, mother, daughter, granddaughter,” she says. Similarly, Ancestors asks poignant questions about those who came before: “Are we held by them on the other side? Does remembering them keep them close?” The seated clay figure depicts a woman with closed eyes gently pressing a small ghost to her face while cradling others in her arm. “She holds the memories of those gone before with great love,” Swentzell says. “I created this piece in dedication to my mother.”

Swentzell’s mother — the late architect, potter, author, and teacher Rina Swentzell — made ceramic plates and cups for her family when Roxanne was young. As virtually all Pueblo potters do, she gave her daughter bits of clay to play with as a young child. For Roxanne, it was life-changing. Unable to express herself easily with words, she used clay to communicate her feelings, most notably shaping a little girl with her head down on her desk to tell her mother she was having difficulty in school. “I’m so grateful that clay was handed down to me, and I handed it to my kids. That passing of the clay is the connection, forward and backward,” she says.

In a studio beside her house, Swentzell creates her figures using the traditional Pueblo pottery method of forming and coiling clay rolls — in her case, very big rolls — to build the walls of the body, head, and limbs. Except with small works like masks or chess pieces, only the fingers and toes are solid. She sculpts the face and other details and fires the figure in an electric kiln.

Swentzell’s artistic mastery and her ability to connect with viewers have earned her numerous honors and awards, including Best of Sculpture at Santa Fe Indian Market, the Spirit of the Heard Award from the Heard Museum, and the Living Treasure Award from Native Treasures Santa Fe. Her work is in the permanent collections of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American Indian, Denver Art Museum, Heard Museum in Phoenix, and the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe, among others.

But for the artist, the most meaningful result of her work is the way it can bridge cultures and people by reflecting back to us the feelings and experiences we all share. “I’m using human emotions to speak about issues or my own personal journey as a way to relay messages, ask questions, or just share,” she says. “That kind of sharing is so vital right now in these times. We’re so hurt and divided, and it’s great to figure out how to find a mutual ground somewhere.”

A Family Legacy in Clay

Generations of ceramic artists in Roxanne Swentzell’s talented extended family carry on the tradition.

When Roxanne Swentzell’s grandmother Rose Naranjo was a child at Santa Clara Pueblo in northern New Mexico, girls and women still carried water in large clay pots balanced on their heads. Gathering and working with the local clay was an integral daily part of Pueblo life. “As far back as we know, pottery was just what you did as a woman in this family,” Swentzell says. Every one of Rose and her husband Michael’s seven daughters and two sons worked with clay at some point, as did Michael.

Swentzell’s uncle, Michael Naranjo, was blinded in the Vietnam War. Shaping clay by feel as a means of healing his inner trauma, he went on to become an acclaimed figurative sculptor whose works are produced in bronze. He and Roxanne would sit together in his studio and form figures from clay when she was a child. Of Rose’s other children, Nora Naranjo Morse is a noted ceramic and mixed media artist; Jody Folwell is an innovative avant-garde ceramic artist; and Dolly Naranjo-Neikrug, Edna Romero, and Tessie Naranjo are also skilled potters. Roxanne’s uncle Tito is a scholar and artist, and his wife, Bernice Naranjo, is an accomplished potter as well.

Roxanne’s generation of award-winning artists includes nationally known contemporary ceramic artist Jody Naranjo; Polly Rose Folwell, who creates exquisite carved pots; Susan Folwell, whose pottery is known for a blending of cultures, incorporating modern imagery with a Native twist; Eliza Naranjo Morse, a mixed media artist and art instructor; and Eli Naranjo Smith, whose traditionally produced and fired pots feature sgraffito (shallowly carved) designs. Bernice and Tito Naranjo’s children, potters Dusty and Forrest, also employ sgraffito in their work.

Now the offspring of these artists are beginning to come into their own. Among them is Swentzell’s daughter, Rose Simpson, a mixed media artist and head of the ceramics department at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe. (Swentzell’s son Porter Swentzell, a historian, also teaches at IAIA.) Polly Rose Naranjo’s daughter, Ka Ojege (Kaa Folwell), works in clay and mixed media; and Tito’s grandson Jonathan Naranjo is a young potter also bridging the gap between traditional and contemporary ceramic art.

“We have groundbreakers in this family,” Swentzell says. “We didn’t stick to traditional pottery — we used it, but we’ve pushed the limits. Some of us are more traditional, but even my grandmother Rose, who came straight out of a lifeway of pots being utilitarian, was already starting to experiment. She let it be OK for the next generation to try different things.”

Roxanne Swentzell is represented by Tower Gallery in Santa Fe. roxanneswentzell.net.

From the August/September 2018 issue.

More From The August/September 2018 Issue

25 Things That Shaped The Western

Bridges On Birmingham

The Iroquois White Corn Project