Early ledger art portrays resistance and resilience on the frontier, while its contemporary pieces tell more modern stories with similar themes.

Imagine a complete folio of ledger art — Plains Indian drawings on old financial ledgers — as a form of 19th-century social media. You page through the drawings, or individual “postings,” of daring acts, romantic exploits, pictures of friends and family, and personal accounts of pivotal events. Other artists join in, “sharing” their own perspectives.

But while social media is ubiquitous, antique Indian art is rare, and authentic ledgers are highly coveted. They speak — with an immediacy and intimacy — to a poignant time in American history, a time when the great herds of buffalo were disappearing, and the proud tribes that once ruled the Plains were being relegated to reservations. “Early ledger art is a first-person narrative of history in the West,” says Henry Monahan, director of Morning Star Gallery in Santa Fe. “It says, ‘I was there and this is what happened.’ ”

The earliest examples were done primarily by artists for their own use. But their drawings soon became a source of income. “Commercialization of ledger art starts with the Fort Marion artists. It’s a process of the non-Indian world appropriating Indian art as trophies and souvenirs,” says Ross Frank, associate professor of ethnic studies at the University of California, San Diego, and director of the Plains Indian Ledger Art project.

Interest in ledger art crosses several genres, appealing to collectors of Native arts, Americana, and Western history. “It’s picking up momentum, accessing bigger artistic collecting spheres, and elevating into a more substantial platform,” says Tom Cleary, director of H. Malcolm Grimmer Antique American Indian Art in Santa Fe. “Collectors are drawn to it because they can connect with it on a visceral level.”

Established collectors tend toward the earlier materials, which can command six figures. They may be interested in specific tribes, military campaigns, or notable figures such as Red Cloud or Sitting Bull. “Collectors of works on paper appreciate the economy of line,” Monahan says. “There’s no frame of reference, no landscape of mountains and trees. Yet it tells an emotional story.”

Scenes Of The Times

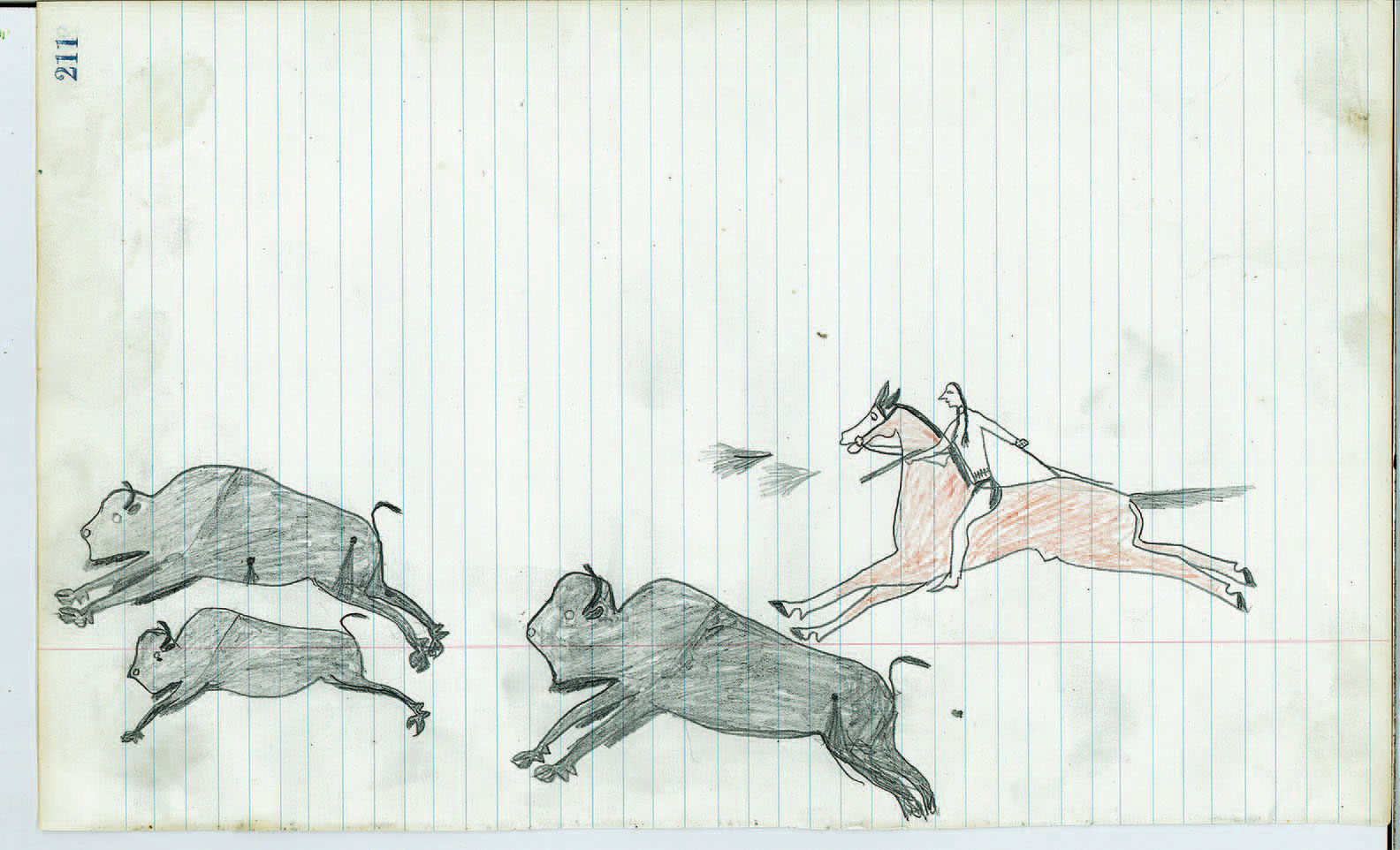

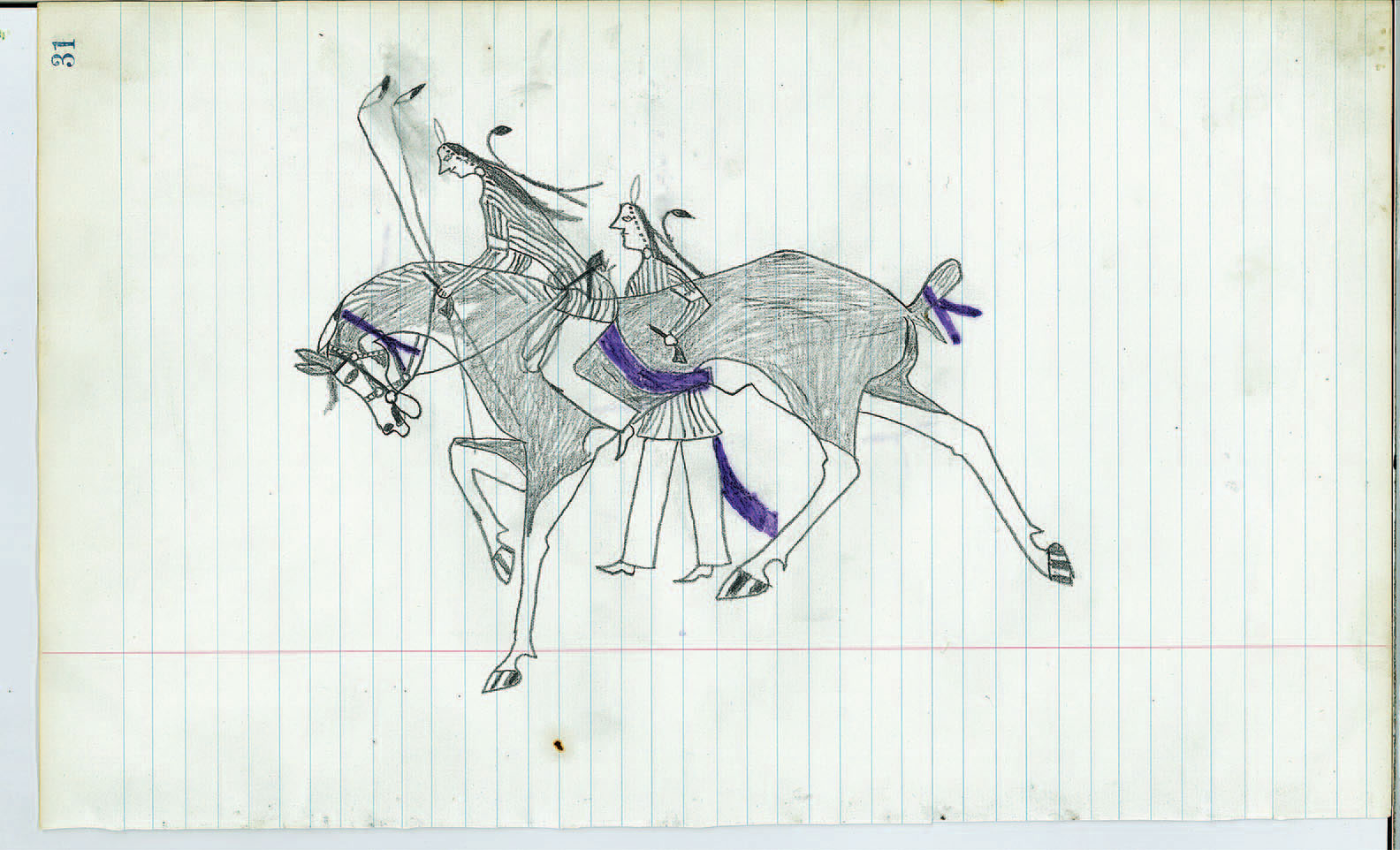

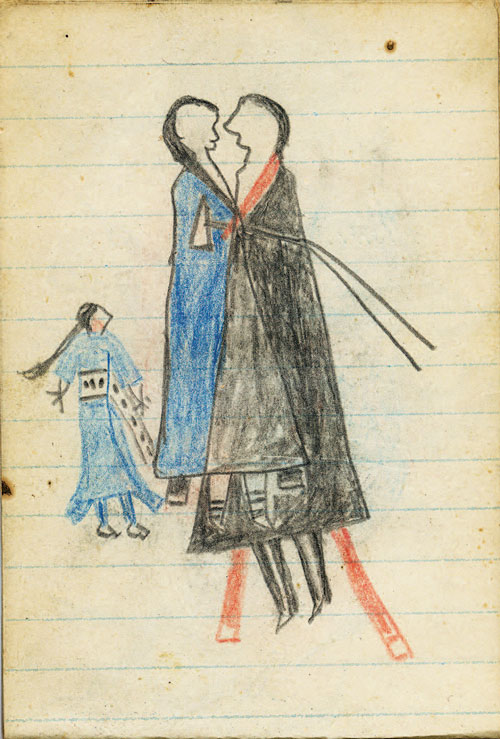

“The pre-1890 work portrays an Indian world that still existed. After 1890, artists are reminiscing about earlier times,” PILA’s Ross Frank says. “You find first-person accounts in the 1860s and pictures drawn by actual warriors. Later battle scenes are likely done by Indian scouts or individuals employed by the U.S. government. The buffalo herds are gone from the northern Plains, but in southern Plains ledger art you still see local deer hunting along with antelope and turkey. You find more courting scenes and ceremonial depictions in the later work, partly because the people who owned the battle stories were passing away.”

John P. Lukavic, associate curator of Native arts at the Denver Art Museum, agrees. “Conquests through love replaced conquests through warfare. While battle scenes were memories of the past, courting scenes were of the moment.” Drawings from the reservation period recount past greatness, depicting ancestors, war exploits from the artists’ youth, and ceremonies that were prohibited on the reservation. “It was almost a form of cultural resistance.”

Because of increased collector interest — and the Antiques Roadshow effect — more ledgers are coming to light. In 1985, two important ledgers were found at a local courthouse sale in Amidon, North Dakota. Many of the drawings were attributed to Jaw, a Hunkpapa Lakota artist.

Scholars prefer that ledger books remain intact, but many books are leafed out, with drawings sold individually. “Books rarely were done by one artist,” Cleary says. “There is growing interest in trying to understand how these books were conceived as entire volumes, and why certain drawings are in certain places. They didn’t come together haphazardly.” Cleary’s gallery presented works from the Amidon ledger at a selling exhibition at the Heard Museum in February 2017, but the ledger books were digitized by the Plains project and will be available for public viewing online. Ledgers are to be offered for sale again August 15 – 18 at the Antique American Indian Art Show in Santa Fe.

Space constraints and light sensitivities prevent institutions from permanently displaying their collections. But many of the finest ledger art examples are now accessible online, including hundreds of high-resolution images from the Milwaukee Public Museum, the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College, and PILA.

New Takes On The Old Tradition

Contemporary artists working on antique ledger papers hark back to historical art, but more often than not, they choose to depict modern Native life. They’re continuing the conversation with an expanded lexicon, and sometimes with biting social and political commentary. Dwayne “Chuck” Wilcox (Oglala Lakota) uses satire and irony in humorous works that hold a mirror to how modern Indians are imagined in works with titles such as Wow! Full Blooded White People! In Terrance Guardipee’s (Blackfeet) signature collages, vividly rendered warriors on horseback race across ledgers layered with antique checks and ration cards atop colorful, modern maps, and railroad advertisements.

Women artists are pushing cultural boundaries in this art form historically reserved for men. Dolores Purdy (Caddo) began making ledger art when she learned that a relative had been held at Fort Marion in 1875. Her unabashedly commercial work combines pop, psychedelia, and wry visual commentaries on pre-20th century paper. Linda Haukaas (Sicangu Lakota) uses historical Lakota motifs in her drawings. Like many contemporary ledger artists, she has expanded the medium to include beadwork and other materials.

The contemporary ledger market is just as robust as that of antique drawings; however, prices tend to be lower for contemporary works. Working artists show at Indian markets and powwows across the West.

A Collector’s Dilemma

Dr. Thomas Jacobsen has a magnificent collection of 22 ledger drawings passed down from his great-aunt Mary C. Collins, who worked as a missionary from 1885 to 1910 on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation. “They gave her the name Winona. She never married, and stayed for 25 years,” Jacobsen says. “Sitting Bull even adopted her into the tribe.” Collins offered the Sioux paper, pencils, and paints when they visited the mission, and she kept the pictures they drew. Her collection passed down through the family, coming to Dr. Jacobsen after his father’s death in the 1960s.

It’s a familiar story: No one in the family was really aware of the art. “My brother gave me a manila folder with the pictures because he knew I was interested in that kind of thing.” They’ve hung on Jacobsen’s walls for decades. “I look at them every day.”

The images are spectacular, depicting warriors and horses on the battlefield. In one scene, a Sioux warrior chases a cavalry rider carrying a flag, which is shown flying upside down. “The artist himself survived and lived to draw it,” Jacobsen muses. The pictures are both exciting and personal. “The artists took time drawing these. They wanted these stories told.”

Jacobsen wants the collection kept intact and displayed — preferably on a family member’s wall. However, none of his children or grandchildren can do so. “I don’t want these to sit in a filing cabinet somewhere,” he says. And that’s a common problem for owners of family collections. Museums eschew accepting collections with stipulations on how the pieces will be used. Even the largest institutions lament the lack of acquisition budgets.

Ross Frank hopes to digitize the collection for PILA, so the pictures Winona’s friends created for her may continue to enthrall viewers online for years to come.

Tips for the Collector

Collectors want to examine, experience, and enjoy ledger art on their walls. But it’s on century-old paper that was never intended to last. So, how do you live with ledger art?

“If you’re comfortable, it’s comfortable,” Halvorson says. “Never store it in a basement, which can be damp, and never in the attic. No direct sunlight. Hang it in a hallway.”

“Colored pencil is more robust than other pigment, and the antique papers, particularly the military ledgers, can be relatively low acid,” Frank points out. “Fort Marion art tends to be in commercial sketchbooks, so they hold up well.”

Growing demand plus readily available antique ledger books equals market mischief. Experts warn that much of the ledger art they see is fake, and anything on eBay should be viewed with skepticism. Watch for a color palette that’s wrong, action that doesn’t make sense, or objects being used incorrectly.

“Become knowledgeable and work with a reputable dealer that sees a lot of ledger art. They’ll be able to recognize an artist’s style,” advises Lewis Bobrick of Denver’s Lewis Bobrick Antiques.

“Collection history is important,” Cleary offers. “Does the drawing come from a known book? New books that come to market should carry documentation of provenance.”

You can’t go wrong buying the best you can afford, according to Monaghan of Morning Star Gallery: “An unremarkable piece does not compare to a work by a top ledger artist such as Joseph Two Horns or Frank Henderson.”

And once you build up your collection, Lukavic suggests trying a variation of what many museums do: “We exhibit drawings for a maximum of six months and then rest them in storage for five years. Why not support working artists by buying several pieces and rotating them on your walls?”

More on Ledger Art

Warrior-Artists in a Tourist Town

From the August/September 2017 issue.