The epic, tragic, and glorious history of Sky City, America’s oldest town.

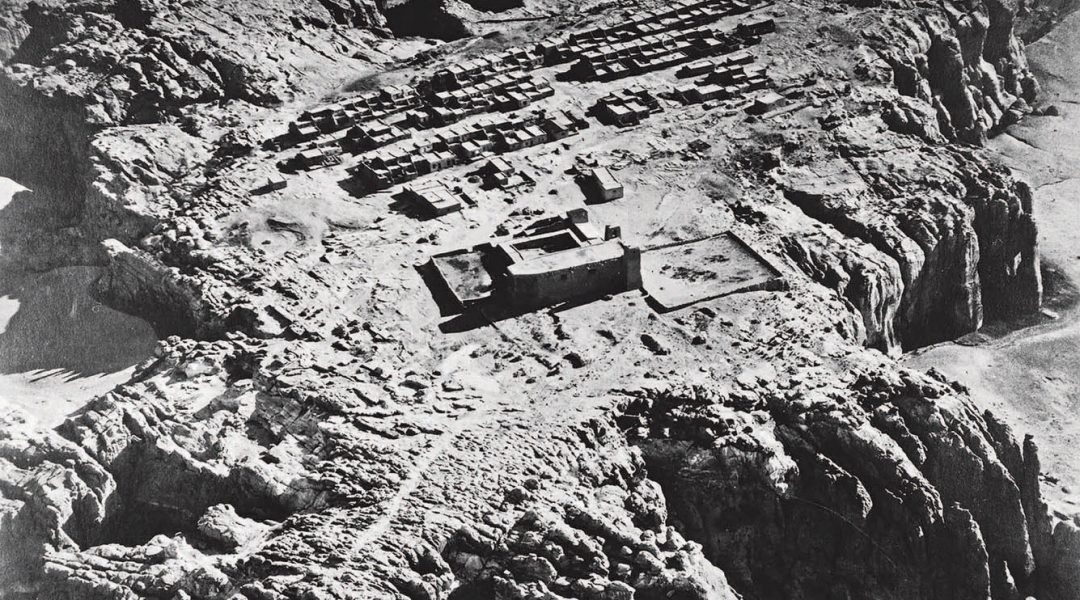

Sixty miles west of Albuquerque, hidden at the top of a dusty, rocky mesa worn down by millennia of rain and wind and footsteps, sits Sky City, the oldest continuously inhabited community in the country. The tiny town is the crown jewel of the ancient Acoma Pueblo Native American tribe.

Today’s Acoma population may be small — about 5,000 people identify as members of the federally recognized tribe — but its back story is one of the most fascinating chapters in American Indian history.

Origin Story

According to Acoma lore, the Pueblo’s roots trace back to a group of wanderers who were told by the gods to go south in search of refuge. Eventually, they found themselves in a glorious valley, looking up at picturesque sandstone bluffs. And that’s where they settled in 1150 A.D., building their village at the top of the area’s tallest mesa. They called it Acoma, meaning “a place prepared,” according to a popular interpretation.

At 365 feet, its isolation provided the perfect defensive position against neighboring tribes, wildlife, and other 12th-century dangers.

Aside from the majestic setting, the village was and still is simple by architectural standards. The adobe brick homes are set up mostly in three rows of interconnecting three-story buildings. Each level connects via ladders, creating a confusing maze of residences that serve as the only way to enter the buildings. The only way up: a hand-carved staircase cut into the sandstone nearly 1,000 years ago.

The village was perfect for a while as the Acoma people lived a peaceful life of solitude, farming corn, beans, squash, turkeys, and tobacco; hunting for antelope, deer, and rabbits; and gathering seeds, berries, nuts, and more.

And that’s the way it stayed until the mid-16th century.

Troubled Relationships

The first time the Acoma Pueblo had contact with the outside world was when Spanish explorers led by Francisco Vázquez de Coronado stumbled across the tiny outpost while heading north from Central America around 1540.

That chance meeting changed the Acoma. They learned new farming techniques from the Spanish and maintained a mutually advantageous relationship for a few decades. It didn’t last long.

By 1598, the relationship with the Spaniards soured when the Acoma learned that a conquistador named Juan de Oñate declared his intent to colonize the Acoma land.

In an effort to defend their homeland, the Acoma ambushed a group of Oñate’s men, killing 11 in the process.

The fiasco didn’t end there. Oñate took revenge in grand fashion, attacking the Acoma with an army in a fierce three-day battle known as the Acoma Massacre, in which the Spanish all but destroyed the Acoma Pueblo and killed more than 600 people.

After the pueblo surrendered, the nearly 500 survivors were put on trial, found guilty, and sentenced by Oñate to extreme punishments. Men and women between the ages of 12 and 25 got 20 years of slavery. Men over the age of 25 received forcible amputation of one foot. The pueblo’s boys and girls were put into the custodianship of various Catholic priests.

By 1606, Oñate resigned from his post and was convicted of cruelty to natives and other colonists. He was banished from New Mexico.

Unfortunately, getting rid of Oñate didn’t bring much peace to the Acoma people.

Introducing Catholicism

By the early 1600s, the Acoma began rebuilding the pueblo but remained under Spanish rule.

That meant Catholic missionaries were spreading to the area, and, in an attempt to convert the Indians, Acoma traditions were suppressed in favor of Catholic traditions. In fact, the Acoma were forced to formally adopt Catholicism.

Most notably, the Spanish friar Juan Ramirez forced the Acoma people to build a massive church. The process included hauling trees, sand, and other construction materials from a local mountain up the steep walls to the top of the mesa.

The result: San Estevan del Rey Mission, now a National Historic Landmark. While the site is impressive and remains a tourist destination to this day, it’s a sore reminder to the modern Acoma people of what their ancestors suffered through.

All the while, the Acoma suffered high mortality from smallpox epidemics introduced by Europeans, as they had no immunity to such infectious diseases.

Eventually, in 1680, American Indians all over New Mexico united to drive out Spaniards in a massive surprise attack, killing 400 Spaniards, and pushing the rest from the region entirely until the Spanish persuaded the pueblo at Santa Fe into a peace agreement in 1692.

The Modern Fight

The colonization of America and later westward expansion of the country brought plenty of other changes to Acoma.

The Acoma spent the 18th, 19th, and even early 20th centuries interacting and negotiating with different groups in a mighty struggle to retain their landholdings.

In the 1920s, the All Indian Pueblo Council gathered to respond to congressional interest in appropriating Pueblo lands. That resulted in the U.S. Congress passing the Pueblo Lands Act in 1924, a major win in the effort to retain their land.

This allowed the Acoma Pueblo to start capitalizing even more on the ever-growing tourism trade opportunities. The most notable of these opportunities is the now-famous Acoma pottery. The art is highly sought after among collectors, and it remains a vital source of income and of cultural preservation for the Acoma.

They also began charging tourists who wished to see the old village and the San Estevan del Rey church. In 2008, the Acoma opened the Sky City Casino Hotel and the Sky City Cultural Center & Haak’u Museum for the nearly 50,000 annual sightseers that flock to see the Acoma Pueblo.

Today, Acoma looks a lot like it did nearly 1,000 years ago. There’s the village on the top of the mesa where about a dozen families live full-time. The rest of the Acoma live in one of the surrounding communities, including Acomita and McCartys. In all, the Acoma Pueblo is now made up of 431,664 acres with about 250 homes.

For centuries, the Acoma have fought to keep their culture alive, resisting all manner of invaders, from Spanish colonizers to westward expansion to the glow of technology. But at every turn, Sky City has persisted, and the mighty community shows no signs of giving in anytime soon.

Sky City is open for walking tours. Visit acomaskycity.org

From the July 2017 issue.