In a little-known historic migration that began in the mid-1800s, some 250,000 orphaned, abandoned, and homeless children were put on westbound trains. We explore the fascinating history with the curator of the national orphan train complex.

It was probably the largest migration of children in human history. From 1854 to 1929, more than 250,000 orphans, runaways, and abandoned children from New York and other cities were sent west and resettled with rural families. At the time, this process was known as “placing out,” but we remember it now as the Orphan Train Movement.

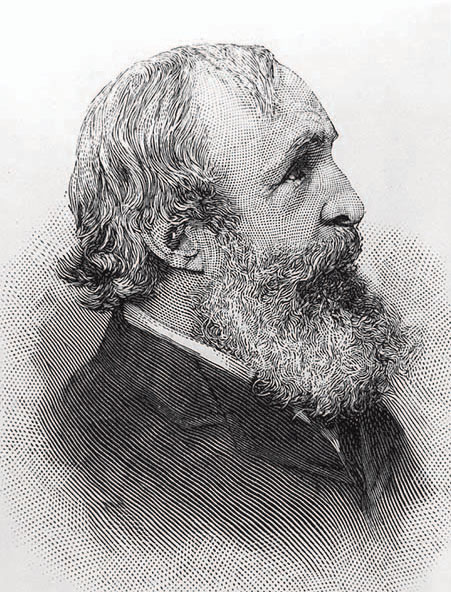

It was the brainchild of an ambitious Connecticut-born minister and social reformer named Charles Loring Brace. Arriving in New York City to study theology in 1848, he was horrified to find thousands of ragged, filthy, half-starved children living on the streets. He couldn’t understand how a benevolent, all-powerful God could allow so many children to live in such misery and degradation, and it shook his faith.

Conditions in the city were dire, the gulf between rich and poor wide. While owners of new factories were building mansions on Broadway, working families could barely afford to rent a single windowless room in a squalid tenement building, even with children over the age of 6 working full time. A thousand immigrants a day were arriving in the city, driving down wages and overcrowding the slums even further. Thousands of children were orphaned by disease. Mothers died in childbirth; fathers were often absent either because they had died in factory accidents or were in prison. Destitute parents put their children into grim Dickensian almshouses because they couldn’t afford to feed them. One survey found more than 10,000 homeless children living on the streets, surviving however they could.

Brace was one of the first to see potential goodness in these children and to recognize them as victims of horrible economic and social conditions. Instead of locking up these unfortunates, Brace wanted to expose them to fresh air, hard work, and wholesome Christian families in the rural American heartland. His first step was to found an organization called the Children’s Aid Society, which established the nation’s first lodging house in New York City. Under its aegis, he began an ambitious new program to place vagrant children in distant family homes. The first orphan train went west in the fall of 1854, the last in 1929. Brace died at age 64, in 1890, a little more than halfway through that run, knowing he had done his job and handing over the reins to sons Robert and Charles Jr. to carry on the work.

The legacy of the Orphan Train Movement would be widely felt. From 1890 onward the CAS led the way in the professionalization of child welfare, including training social workers and foster parents. Among the program’s many success stories were orphan train riders who became judges, college professors, bankers, journalists, physicians, farmers, ranchers, clergymen, artists, high school principals, and the wives of men at all levels of society. Two became members of Congress. Some of them and their many descendants would help shape the West.

C&I spoke with Shaley K. George, curator of the National Orphan Train Complex in Corcordia, Kansas, about the movement, its founder, its riders, and its enduring influence on the country and the West.

Cowboys & Indians: Give us the basic overview of the Orphan Train Movement.

Shaley K. George: The Orphan Train Movement ran from 1854 to 1929 and sent an estimated 250,000 children from East Coast cities across the 48 contiguous United States and five continents. Some of the children were truly orphaned; others were half-orphaned, abandoned, and homeless. The first company of 46 children was sent to Dowagiac, Michigan, and arrived October 1, 1854. It took them two boats and two trains to reach their destination. The last known train arrived on May 31, 1929, in Sulphur Springs, Texas, with three children aboard. An estimated 75 to 80 percent of the children found good homes; an even higher percentage went on to be successful individuals, spouses, parents, and friends. They were resilient and chose to succeed.

C&I: In what way is the Orphan Train Movement a Western story?

George: The Orphan Train Movement’s role in westward expansion is not discussed, but the fact is that the children who were being sent from the streets and orphanages of the East to Western homes would go on to help develop the nation as we know it today. They are similar to the settlers who came before them. They came from the East, they lived lives they could not have planned for, and they largely succeeded, helping to develop untamed lands and settle the frontier.

The railroads, of course, play an enormous role in the Western story, and their role in the Orphan Train Movement is no different. A common misconception is that children were only sent to farming communities to become laborers. This is not true. The Children’s Aid Society of New York sent the largest number of children to the Midwest. By 1890, the largest concentration of rail lines in the U.S. was in exactly the same Midwestern states where the CAS sent the most children. These towns had schools, churches, and a community to teach needy children what love and family were about.

The conception of the West was ever-evolving in the minds of Americans during the 1800s. With the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the country doubled in size, and the 1840s brought the West Coast and Southwest onto the country’s horizon. By the 1850s, the largest migration of pioneers using the trails was complete and the railroads were moving in. Charles Loring Brace knew that with the technology of the railroads he could place out more children. Without the trains, the placing-out program would not have been as widespread and overall as successful.

Throughout [the] Children’s Aid Society’s annual reports, the phrase “sent west” is traditionally used to signify a company of children being placed outside New York City to the Midwest and farther west. The United States was a growing nation with land that was “unsettled.” When we think of the Wild West today, Dodge City, Kansas, and Deadwood, South Dakota, top the list — both are in Midwestern states. The CAS began placing out its children in surrounding states and the Midwest, spreading its efforts farther out every year. The first Western state to receive children was Colorado in 1872.

C&I: What was the Rev. Charles Loring Brace’s idea of the West that he was sending these orphans to?

George: Father of the orphan trains, Brace, in my opinion, had an idealistic view of the West, as many in the East did. He saw Western families offering the forgotten children of New York City a life full of education, faith, and success. In Brace’s book The Dangerous Classes of New York, & Twenty Years’ Work Among Them, published in 1872, he states, “In every American community, especially in a Western one, there are many spare places at the table of life. There is no harassing ‘struggle for existence.’ They have enough for themselves and the stranger too. Not, perhaps, thinking of it before, yet, the orphan being placed in their presence without friends or home, they gladly welcome and train him.”

C&I: What programs were put in place to support this altruistic idea that led to such a massive migration?

George: What we now refer to as orphan trains were actually called placing-out programs and mercy trains during the Orphan Train Movement, depending on which sending organization was placing the child. There were roughly 30 organizations that placed children, with three main organizations — the Children’s Aid Society, the New York Foundling Hospital, and the New York Juvenile Asylum — doing the majority of the placing.

The Children’s Aid Society and its founder, Charles Loring Brace, created the American placing-out programs and influenced the creation of all others that followed. The CAS would place out the most children — more than 150,000 confirmed — and run the largest aid organization in New York City, complete with schools, lodging houses, and out-of-city retreats. The CAS never opened an orphanage of its own; its main purpose was to get children out of orphanages. They would take children from orphanages across New York City, New York state, and the East Coast. The Home for the Friendless [in St. Louis] was one such orphanage. It was run by the American Female Guardian Society. They placed children out in Western foster homes while also sending children on CAS orphan trains.

The CAS program evolved over its 75-year run but was considered the traditional orphan train placing-out program. One or more towns would be selected to receive a company of children. Two weeks before the children arrived, a CAS agent would visit the community to set up the hotel and the meeting location — often an opera house, where a stage instantly elevated the children subconsciously in the eyes of the crowd — and to set up the local placing-out committee. The local committee would accept applications from potential parents.

C&I: How rigorous were these programs? After placement, was it out-of-sight, out-of-mind, or was there some accountability?

George: By 1890, the application was three pages long and required such information as five non-family references. When the children arrived two weeks later, a large crowd would greet them at the depot. They would rest and dress in their Sunday best at the hotel; they would then make their way to the meeting location. The agent would give a sermon on the purpose of the programs, the attributes of each child, and the requirements of potential parents. The committee would then select the best parent for each child. Often there were multiple parents willing to take each child.

From the beginning of the program in the 1850s and onward, agents checked in on children multiple times a year until their 18th birthday, and the child or family corresponded via letter at least twice a year. We have solid evidence that agents went above and beyond for their children. Agent Anna Laura Hill spent 30 years as a placing agent, placed out more than 160 companies of children, and covered all checkups in Kansas. She never left home without her camera, which she used to document her checkups; more than 200 images survive today, including many showing placed children with pets at their adoptive homes. She kept her own records, which helped her later reunite siblings. The Rev. H.D. Clarke spent 10 years as a placing agent, but for the rest of his life received at least two letters a day — he answered every single one. The agents served as surrogate mothers, fathers, and grandparents to their children. They have rarely been depicted accurately in media.

C&I: Part of the arrangement was that no child was expected to do more than a birth child, though sadly we know this agreement was not always adhered to. At the same time, attitudes about child labor were different then, and even some of the orphan train riders have cautioned people about judging those days and their experiences against contemporary notions of childhood. Not to mention the alternative — the dire situations these children faced had they stayed in New York.

George: No matter what historical event or time, nothing is black and white. The Orphan Train Movement for decades was and still is painted as a dark piece of American history. However, the mass majority of orphan train riders said differently. The historical records kept by sending organizations and the actions of the placing agents say differently. Snap judgments were made about sending children across the country without considering the harsh reality of the cities they were leaving behind. Poverty was rampant in New York City; the tenements were growing in population as more people came to the city. Families were one epidemic away from losing a parent [or could lose a parent] through a workplace accident, death during childbirth, illness — anything could happen, and children could wind up orphans in the blink of an eye. Aid was not readily available and strings were attached. If you were found undeserving, you were not going to be helped. Children on the street faced not just the elements, but also disease, starvation, adult predators, child labor, turning to prostitution.

An overcrowded orphanage was not the answer — it gave children a home until they turned 18, only to cast them out onto the streets they had saved them from and relegate them to a cycle of poverty from which they would never escape. Brace did much more than place out 150,000 children through the Children’s Aid Society. The CAS inspired at least 29 other sending organizations to place out children, bringing the estimated total to 250,000 children placed via orphan trains. His work created the path to child services and social services as we know them today. His ideas influenced the Progressive Era, and his presence is still felt.

In the past 30 years since the founding of the Orphan Train Heritage Society of America, which became the National Orphan Train Complex, researchers have discovered that to truly understand the Orphan Train Movement, we have to look at it from every angle. That means every sending organization, organization founder, donor, orphanage, placing agent, placing-out committee, orphan train rider, birth family, adoptive family, orphan train descendant, etc., needs to be considered.

C&I: In that process, you have collected lots of testimonies from the riders themselves, some of whom are still living. What are some of their stories?

George: An estimated 30 orphan train riders are still living. If a child was placed out as an infant in 1929, the youngest rider would be turning 88 in 2017. We know riders living in Arizona, Texas, Kansas, Missouri, Idaho, and Iowa. Some children placed out as infants were never told they were adopted and could still not know their orphan train origins. Anne Harrison was one such child.

At the age of 27, Anne discovered she was adopted when she walked into the St. Vincent Ferrer Catholic Church in New York City to request her baptismal record. Anne had been raised in Colorado Springs, Colorado, and taken for granted that she was the birth child of the Grueles. Upon discovering the church held no records under her name, she was sent to the New York Foundling Hospital only blocks away (the Sisters of Charity who ran the hospital always baptized their new infants at St. Vincent Ferrer church). There Anne discovered the truth: She was requested by the Grueles and sent west at the age of 2½. Her parents never told her — they loved her and never wanted her to feel less than their daughter. After years of waiting and searching, Anne finally received her birth certificate in 1989. Her mother had immigrated from Russia and her father was a native New Yorker, both Jewish. Anne began to laugh! After discovering her heritage she was quoted saying, “Not to worry! I got the best of both Testaments!” Anne became a fierce advocate for orphan train riders and wonderful friend of the National Orphan Train Complex. We miss her dearly.

As for some of the other stories we’ve collected, William Finn, who was born in 1848, was placed out by the Children’s Aid Society in 1859. He found a loving home in Rockford, Illinois, with the Hollister family. In 1864, at the age of 16, he enlisted in the Union Army, the same army his foster father was also serving in. William left his foster home in 1869 for Sedgwick County, Kansas. He would become the first schoolteacher and Sunday school teacher, teaching out of an old Army dugout. In 1870, he drew the first plat map of Wichita, Kansas, and a large portion of Sedgwick County. William’s description of the beautiful countryside led his foster family to move to Kansas. He would become a leading figure in Wichita; he passed in 1929.

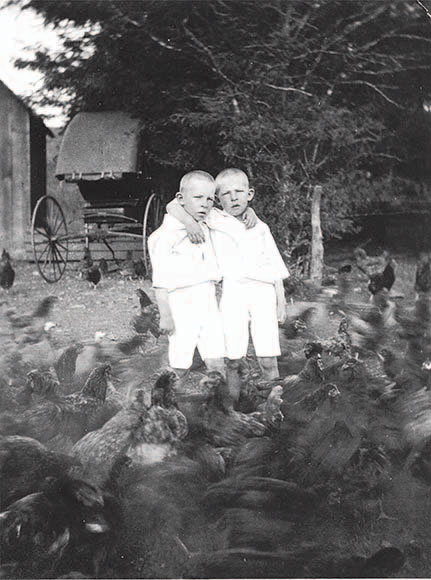

A new favorite, about the McIntire brothers, comes from Lori Halfhide [a head researcher at the museum who handles genealogical requests]. There were five known children of Moses and Rebecca McIntire. After the parents died just over a year apart, the children were turned over to the Brooklyn Orphan Asylum. Alexander, the oldest at about 12, did not go to the orphanage, choosing instead to remain in New York and make his own way. In June of 1876, William, 11; John James, 9; Sarah, 7; and Joseph, 4; were transferred to the Children’s Aid Society to be sent west on an orphan train. William, John, and Sarah wound up in Cherokee County, Iowa. It wasn’t long until older brother Alexander made his way to Cherokee County, Iowa, as well. William and Alexander McIntire left Iowa and headed west, wandering through mining camps in Colorado and learning. In 1898, William and Alexander settled in Elizabethtown, New Mexico, and were mining in the Bobtail Mine. Two years later they leased the Gold and Copper Deep Tunnel Mine, which they ran until 1929. Alexander and William gave up mining and bought a tourist camp near Brazoria, Texas. Youngest brother Joseph, who had wandered along the West Coast for most of his life, had joined his brothers and helped them run their tourist camp on Oyster Creek. William passed away in 1930. Alexander eventually made his way back to Iowa to spend the rest of his life with his sister, Sarah, and her family. John James McIntire had married and had a family; they moved to San Diego, where he passed away in 1911.

C&I: Learning about the lives of the riders makes it a very personal kind of history. As it turns out, you have your own personal connection to the Orphan Train Movement in addition to your job. How does your own history as a cowboy-boot-wearing, seventh-generation Wyomingite inform the work you do at the National Orphan Train Complex?

George: Growing up in a small town in beautiful Wyoming gives me an understanding of the kinds of communities these children were brought to and the idealistic view the big-city folks had of these communities because I grew up holding the same idealistic view of the Old West. I am also adopted. I have the most wonderful set of parents and have been blessed in finding my birth families. Being adopted made me want my job and makes me want to do it better all the time. I am able to understand the orphan train rider descendants’ desire to know where they come from even though they love where they ended up.

When I started my job in July 2014, I had never heard of the Orphan Train Movement, and I had a lot of catching up to do. About two months into the job, my mother’s aunt informed me that my great-grandmother had a brother off the orphan train! I had no idea. Stars align at the complex in very strange ways every day, and this is just one example. It solidified the gut feeling I had when I instantly decided to apply and ultimately accepted the job offer to work at the National Orphan Train Complex. The Lord works in mysterious ways. He did back during the Orphan Train Movement, and he continues to in the lives of the families of its riders.

C&I: How does the Orphan Train Movement continue to shape the country, especially the West?

George: On a larger scale, the Placing Out Program, the Children’s Aid Society, and their ties to politics led to changes that last today. Many members of the Roosevelt family — including Theodore “Thee” Roosevelt Sr., Theodore Roosevelt, and later Franklin Delano Roosevelt — were involved with the Children’s Aid Society and the development of child and family rights and welfare.

Most significantly, there are more than 2 million orphan train rider descendants in America today. They carry on the legacies of their ancestors. Miriam Zitur, who was placed out by the New York Foundling Hospital, currently has over 200 direct descendants. However, the impact of one’s legacy cannot be measured in quantity. John Lukes Jacobus had one daughter who has carried on his legacy of love, kindness, and curiosity and shares the history of the Orphan Train Movement through presentations and working with National History Day students. Once you start learning about the orphan train riders and their families, you begin to understand the magnitude of what one life can do and mean.

Find out more about the National Orphan Train Complex and the Orphan Train Movement online. Read the story of two orphan train riders who grew up to be the governors of Alaska and North Dakota here.

From the May/June 2017 issue.